Like in the old days, I came out of the dry creek behind the house and did my little tap on the kitchen window.

“Get in here, you,” Ma said.

Inside were piles of newspapers on the stove and piles of magazines on the stairs and a big wad of hangers sticking out of the broken oven. All of that was as usual. New was: a water stain the shape of a cat head on the wall above the fridge and the old orange rug rolled up halfway.

“Still ain’t no beeping cleaning lady,” Ma said.

I looked at her funny.

“Beeping?” I said.

“Beep you,” she said. “They been on my case at work.”

It was true Ma had a pretty good potty mouth. And was working at a church now, so.

We stood there looking at each other.

Then some guy came tromping down the stairs: older than Ma even, in just boxers and hiking boots and a winter cap, long ponytail hanging out the back.

“Who’s this?” he said.

“My son,” Ma said shyly. “Mikey, this is Harris.”

“What’s your worst thing you ever did over there?” Harris said.

“What happened to Alberto?” I said.

“Alberto flew the coop,” Ma said.

“Alberto showed his ass,” Harris said.

“I hold nothing against that beeper,” Ma said.

“I hold a lot against that fucker,” Harris said. “Including he owes me ten bucks.”

“Harris ain’t dealing with his potty mouth,” Ma said.

“She’s only doing it because of work,” Harris explained.

“Harris don’t work,” Ma said.

“Well, if I did work, it wouldn’t be at a place that tells me how I can talk,” Harris said. “It would be at a place that lets me talk how I like. A place that accepts me for who I am. That’s the kind of place I’d be willing to work.”

“There ain’t many of that kind of place,” Ma said.

“Places that let me talk how I want?” Harris said. “Or places that accept me for who I am?”

“Places you’d be willing to work,” Ma said.

“How long’s he staying?” Harris said.

“Long as he wants,” Ma said.

“My house is your house,” Harris said to me.

“It ain’t your house,” Ma said.

“Give the kid some food at least,” Harris said.

“I will but it ain’t your idea,” Ma said, and shooed us out of the kitchen.

“Great lady,” Harris said. “Had my eyes on her for years. Then Alberto split. That I don’t get. You got a great lady in your life, the lady gets sick, you split?”

“Ma’s sick?” I said.

“She didn’t tell you?” he said.

He grimaced, made his hand into a fist, put it upside his head.

“Lump,” he said. “But you didn’t hear it from me.”

Ma was singing now in the kitchen.

“I hope you’re at least making bacon,” Harris called out. “A kid comes home deserves some frigging bacon.”

“Why not stay out of it?” Ma called back. “You just met him.”

“I love him like my own son,” Harris said.

“What a ridiculous statement,” Ma said. “You hate your son.”

“I hate both my sons,” Harris said.

“And you’d hate your daughter if you ever meet her,” Ma said.

Harris beamed, as if touched that Ma knew him well enough to know he would inevitably hate any child he fathered.

Ma came in with some bacon and eggs on a saucer.

“Might be a hair in it,” she said. “Lately it’s like I’m beeping shedding.”

“You are certainly welcome,” Harris said.

“You didn’t beeping do nothing!” Ma said. “Don’t take credit. Go in there and do the dishes. That would help.”

“I can’t do dishes and you know that,” Harris said. “On account of my rash.”

“He gets a rash from water,” Ma said. “Ask him why he can’t dry.”

“On account of my back,” Harris said.

“He’s the King of If,” Ma said. “What he ain’t is King of Actually Do.”

“Soon as he leaves I’ll show you what I’m king of,” Harris said.

“Oh, Harris, that is too much, that is truly disgusting,” Ma said.

Harris raised both hands over his head like: Winner and still champ.

“We’ll put you in your old room,” Ma said.

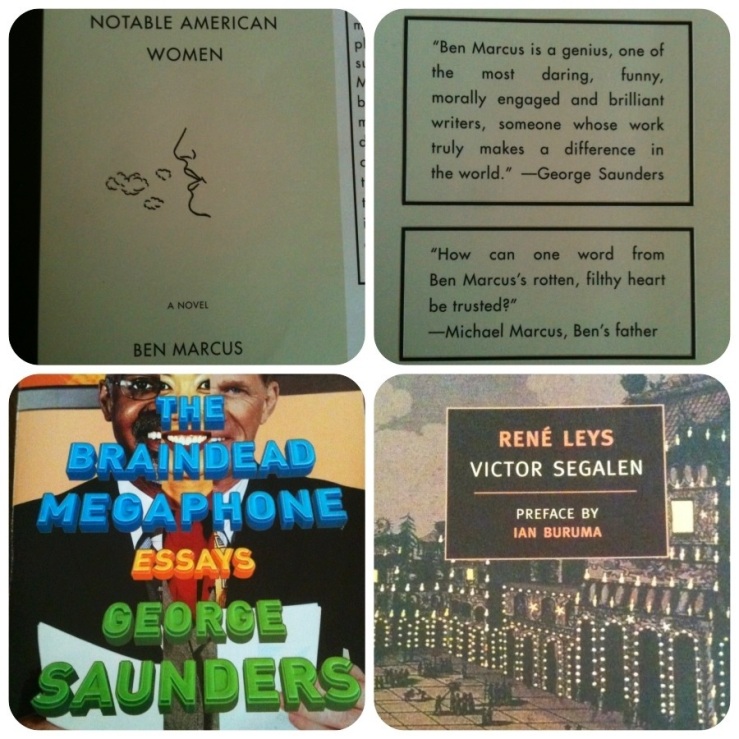

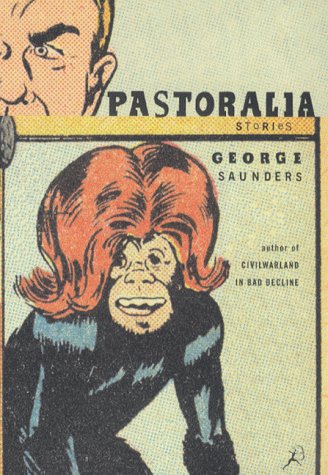

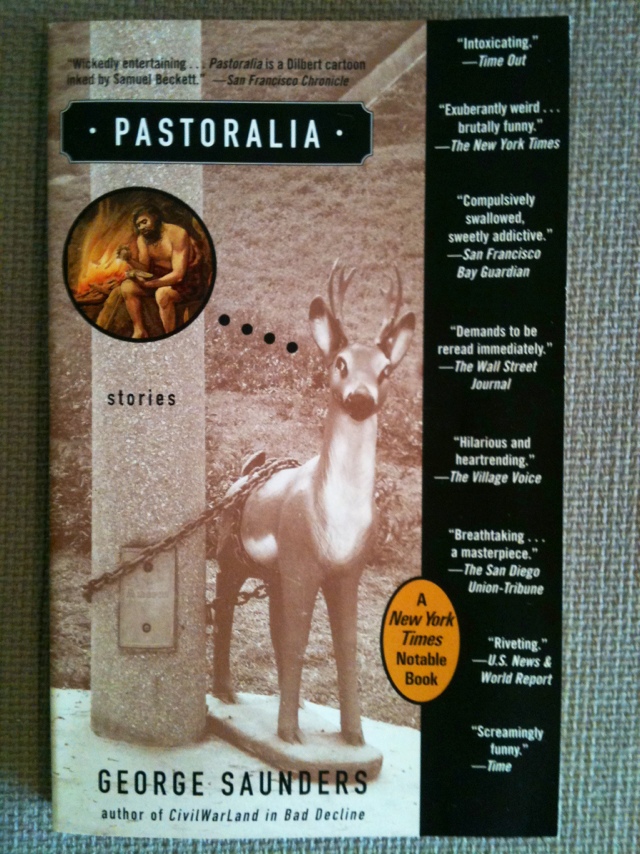

I read Pastoralia, George Saunders’s 2000 collection of stories very quickly, consuming one or two of the book’s six stories a night, usually wedged between other readings. There was a flavor of respite to these readings, a sense of ease or relaxation or—dare I say it—simple pleasure. Frankly, I’m suspicious of any book that I’m able to read very quickly; perhaps I’m prejudiced against any book that doesn’t pose (or impose) its own learning curve on the reader.

I read Pastoralia, George Saunders’s 2000 collection of stories very quickly, consuming one or two of the book’s six stories a night, usually wedged between other readings. There was a flavor of respite to these readings, a sense of ease or relaxation or—dare I say it—simple pleasure. Frankly, I’m suspicious of any book that I’m able to read very quickly; perhaps I’m prejudiced against any book that doesn’t pose (or impose) its own learning curve on the reader.

Via

Via