The strongest and strangest literature usually has to teach its reader how to read it, and, consequently, to read in a new way. Jason Schwartz’s new novella John the Posthumous is strong, strange literature, a terrifying prose-poem that seizes history and folklore, science and myth—entomology, etymology, gardening, the architecture of houses, the history of beds, embalming practices, marital law, biblical citations, murder, drowning, fires, knives, etc.—and distills it to a sustained, engrossing nightmare.

What is the book about? Was my list too choppy? Our unnamed, unnameable narrator tells us, late in the book: “Were this a medical, rather than a marital history—you might then excuse so conspicuous a series.” (His series, of course, is different from mine—or perhaps the same. John the Posthumous, as I’ll suggest later, is a series of displacements).

So, John the Posthumous is a marital history. There. That’s a summary, yes? Ah! But there’s conflict! Yes, this is a book about adultery, about cuckoldry! (“Cuckoldry, my proper topic . . .”). Adultery is threaded into the titles of the three sections Schwartz divides his novella into: “Hornbook” — “Housepost, Male Figure” — “Adulterium.” There’s something of a poem, or at least a poetic summary just there.

Do you sense my anxiety about writing about the book? Some need to deliver a summation? Perhaps I’m going about this wrong. How about a sustained passage of Schwartz’s beguiling prose. From the first book, the “Hornbook”:

The lake is named for the town, or for an animal, and is shaped like a blade.

Adulterium, as defined by the Julian Statute, circa 13 B.C., offers fewer charms, given the particulars of winter, not to mention various old-fashioned sentiments concerning execution. Mutilation, for its part, is more common—the adulterous wife, or adultera, to use the legal term, surrenders her ears or nose, and, on occasion, her fingers—with divorce following in short order. Some transcriptions neglect the stranger, or adulterer, in place of graves—a simple matter of manners, this, not withstanding the disquisition upon the marriage bed. Others relate ordinary household details—dismantling the chairs, and visiting the windows, and departing the courtyard.

A gentleman, remember, always averts his eyes.

Cuckold’s Point, near Brockwell, in London, is most notable for its gallows—the red sticks recall horns—and for the drowning of dogs.

Schwartz’s narrator’s sentences do not seem to flow logically into or out of each other. They seem to operate on their own dream/nightmare logic, as if the words of John the Posthumous were the concordance to some other book. The single line paragraph about the lake (source of its name not entirely determined; its shape best expressed in simile) shifts into a horrific legal history of adultery and then into Cuckold’s Point, a bend in the Thames that owes its name to a simile.

Simile is perhaps the dominant mode of John the Posthumous. Schwartz’s narrator condenses and expands and displaces his objects, his characters, his themes. Sentences sometimes seem to belong to other paragraphs, as if multiple discursive discussions wind through the book at once. Our narrator tells us that

The common wasp measures roughly two hundred hertz. This is well below the frequency of, say, a human scream. Anderson compares the sound of a dying beetle with the sound of a dying fly. (The names of the families escape me at the moment.) The common bee, absent its wings, is somewhat higher in pitch. (Carpenter bees would swarm the porch in August.) The true katydid says “Katy did” — or, according to Scudder, “she did.” The false katydid produces a different phrase altogether, something far more fretful. Wheeler concludes with the house ant and the rasp of a pantry door. Douglas prefers a hacksaw drawn across a tin can. (We found termites in the bedclothes one year.) A sixteenth note, poorly formed, may be said to resemble a pipe organ or a hornet. The children set their specimens on black pins.

Here, entomologists (note how Schwartz always pulls his language from his reading, his research) try to describe the language of insects. Interspersed we get images of mutilation and impalement (“The common bee, absent its wings”; “The children set their specimens on black pins”) along with interjections of insects infesting intimate domestic spaces (“We found termites in the bedclothes”). The passage also picks up the novella’s motif of sharp objects (“a hacksaw drawn across a tin can”). There’s something simultaneously banal and horrifying about the tone of this passage, its language a juxtaposition of scientific observation and cloudy personal recollections—all contrasted with “the frequency of, say, a human scream.”

Infestation, violence, and betrayal shudder throughout John the Posthumous, erupting in strange moments of deferral and transference: “When the horse becomes a house, furthermore, termites appear on the floor,” reads one bizarre line. “A woman says ‘dear’ or perhaps ‘door,’ and then two names—or perhaps only one,” we’re told. “Even the earliest primers compare the heart’s shape to a fist or to a hand waving goodbye,” the narrator points out.

At one point, the narrator laments: “how I regret these grisly, inexpert approximations.” In context, he’s working through a series of etymologies (linking shroud to groom and wishing that dagger had some connection to dowager), but the phrase—“grisly, inexpert approximations”—approaches describing the narrator’s program of deferral and displacement.

Etymology repeatedly allows the narrator (an approximation of; an attempt at) a basis of description:

The doorframe disappoints the wall, as the wall disappoints the door. The mullions divide the yard into nine portions. But portions—or, if you like, portion—is an unlovely word. Guest and host, for their part, issue from the same root—ghostis. Which means stranger, villain, enemy—though naturally I had believed it to mean ghost. And the figure in the corner, lower right, is neither my daughter nor her hat, but just a paper bag in the grass.

The passage is remarkable. We begin with the mundane but symbolically over-determined image of a doorframe, along with an equally mundane wall and door—all connected, bizarrely, with the verb disappoints, producing an uncanny effect. The mundane mullions that divide the yard reveal the perspective of our narrator. He is looking out. He seems to be trapped in a house, but the house is always displaced, shifting—it’s many houses. Portion leads him etymologically to ghostis (a root I’ve long been obsessed with), a word that condenses a series of oppositions—and, as the narrator points out, provides its own imaginary ghost. The final sentence shifts us again; it seems to belong to another paragraph. But perhaps not. Perhaps we continue to survey the wall, the door, the mullions—do we look out the window and see the figure that is not (and thus, in the realm of the narrator’s program of imaginative displacement, is, or rather, approximates) his daughter or her hat? Is it a photo on the wall? Both?

I’m tempted to keep on in this manner, pulling out passages from John the Posthumous and riffing on them, but maybe that’s a disservice to its potential readers, who I think should like to be assimilated by its strange strength on their own terms. Schwartz’s narrative doesn’t cohere so much as it enmeshes the reader, who must learn a new way of reading, of grasping (or releasing) his series of objects and histories and rumors and rituals.

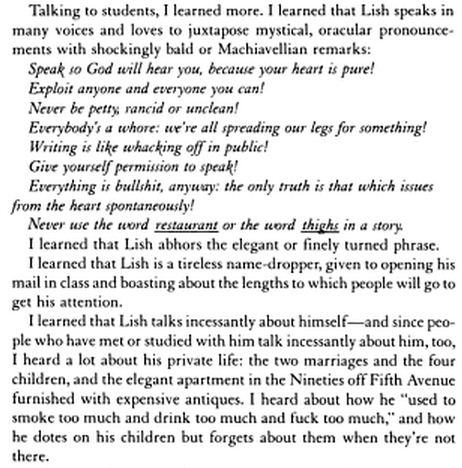

The novelist and editor Gordon Lish (who has championed Schwartz) famously advised: “Don’t have stories; have sentences.” Great writing happens at the syntactic level, which cannot be separated from plot—the language is the plot. John the Posthumous embodies this aesthetic, creating its own idiom, composed from the real and the imaginary and the symbolic, an idiom that refuses to yield a straightforward calculus or grammar. The effect is wonderfully frustrating; the novel nags at the reader, confounds the reader, haunts the reader.

Haunt has its own strange etymology, likely deriving from the Old Norse heimta, “to return home,” through to Old French hanter, “to be familiar with,” popping up in Middle English haunten, “to use, to reside.” We can take it all the way back to the Proto-Indo-European root kei — “lie down, sleep, settle, hence home, friendly, dear.” Etymologically, all houses are therefore haunted—the series of houses (all different, all the same) in John the Posthumous especially so. This is a horror story, a haunted house story, a story larded with killers and connivers and adulterers. Another passage (I promise just to share this time and withhold remarks):

In the cellar: a pull saw and a hasp, a jack plane, a wrecking bar, and a claw hammer. A tin contains a cap screw and a razor blade. A jar contains the remains of a carpet beetle.

I dismantle the chairs and place all the parts in a crate. I station the broom beside the garden spade.

The killer in the cellar, in folklore, is discovered by a mute child. The prisoner in the cellar survives a fire or a storm—but is later mauled by wolves.

There were fleas last year, and squirrels the year before that.

I feel like I’ve offered enough of Schwartz’s uncanny prose here to appropriately intrigue or repel readers. The vision here is dark and the prose imposes an alterity that the reader must work through. This book is Not For Everyone, but it might be for you—I loved it. Haunting, frustrating, and disturbing, John the Posthumous is one of the best new books I’ve read this year.

John the Posthumous is new in trade paperback and e-book from OR Books on August 6th, 2013.

Listening to Gordon Lish read selections from

Listening to Gordon Lish read selections from  Hey. Do yourself a favor and listen to

Hey. Do yourself a favor and listen to