From Kafka’s unfinished and very strange story “Memoirs of the Kalda Railway.” Collected in Diaries.

From Kafka’s unfinished and very strange story “Memoirs of the Kalda Railway.” Collected in Diaries.

Kafka doodle. From his Diaries (vol.1).

(From a 1910 diary entry).

From “Malcolm Lowry: A Remininiscence,” the final chapter of David Markson’s Malcolm Lowry’s Volcano, a study of Under the Volcano:

His big books, however, would at the moment remain these: Moby-Dick, Blue Voyage, the Grieg, Madame Bovary, Conrad (particularly The Secret Agent), O’Neill, Kafka, much of Poe, Rimbaud, and of course Joyce and Shakespeare. The Enormous Room is a favorite, as is Nightwood. Kierkegaard and Swedenborg are the philosophers most mentioned, and in another area William James and Ouspensky. Also Strindberg, Gogol, Tolstoy.

Lifting a Maupassant from the shelf (nothing has been said of the man before this): “He is a better writer than you think.”

I saw Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky’s at the bookstore last week, read the first few pages of the first story, and had to have it. (Although the NYRB logo is always enticement enough). From Liesl Schillinger’s review in the NYT:

Krzhizhanovsky’s stories are more like dream diaries than fiction. Quite intentionally, he blurs the line between sleep and waking, real and unreal, life and death. While his translators admirably convey the whirligigging quality of his narratives, Krzhizhanovsky’s peregrinations demand unstinting focus and frequent compass checks. His characters often seem half, or wholly, asleep. Sometimes, as in “The Thirteenth Category of Reason,” they are dead — which doesn’t stop them from boarding city trams and chatting with commuters. “Alive or dead, they didn’t care.” Their only concern is whether such conduct is “decrimiligaturitized” — that is, legal. “In “Quadraturin,” the man with the proliferspansion ointment never exits a state of benumbed grogginess. Lying on his bed, “unable to part eyelids stitched together with exhaustion,” he tries to sleep through the night, “mechanically, meekly, lifelessly.” When inspectors from the Remeasuring Commission drop by to make sure he hasn’t exceeded his allotted 86 square feet of space, he hovers, terror-stricken, at the door, hoping they won’t spot his infraction. It’s an archetypal nightmare, reminiscent of Kafka.

1. How to go about this?

A starting place:

Clarice Lispector’s 1977 novella The Hour of the Star is a superb collection of sentences.

2. But what do I mean by this ridiculous statement? I mean isn’t that what all or most writing amounts to–a “collection of sentences”?

What I mean then is that Lispector’s sentences prickle and tweak and glare, launch off in strange angles from each other as if they were building out narratives in disparate, separate tones, moods, colors.

3. Another way to say this: the writing is strange, marvelous, uncanny. The good weird.

4. Or maybe I should let Lispector’s narrator say it:

Remember that, no matter what I write, my basic material is the word. So this story will consist of words that form phrases from which there emanates a secret meaning that exceeds both words and phrases.

(Our narrator repeatedly invokes the power of “the word,” but I’ll linger on the way those words string together in sentences).

5. And yes, our narrator is a “he.” Clarice Lispector the ventriloquist. Early in the book the narrator says that the tale could only come from “a man for a woman would weep her heart out.”

6. I’ll be frank: I don’t know how to unpack all the ventriloquizing here, the layering between Lispector and her narrator Rodrigo S.M., who relates the sad tale of Macabéa (a typist!), indigent slum-dweller, no talent and no beauty.

7. Narrator Rodrigo S.M. seems unsure himself how to unpack the tale. He spends almost the first fifth of the book dithering over actually how to begin to start to commence:

I suspect that this lengthy preamble is intended to conceal the poverty of my story, for I am apprehensive.

And a page or two later:

I am scared of starting. I do not even know the girl’s name. It goes without saying that this story drives me to despair because it is too straightforward. What I propose to narrate sounds easy and within everyone’s grasp. But its elaboration is extremely difficult. I must render clear something that is almost obliterated and can scarcely be deciphered. With stiff, contaminated fingers I must touch the invisible in its own squalor.

8. (I promise to pick back up on that squalor and whatever invisible might be at the end of this riff).

9. The Hour of the Star: The story is thin, the plot is a shell, a threadbare ancient trope, as brave Rodrigo S.M. repeatedly tells us.

10. The plot is archetypal even. The orphan girl in the big city. Cinderella who imagines the ball, or tries to imagine the ball. Etc.

11. So here’s a proper plot summary, c/o translator Giovanni Pontiero (who surely deserves large praise heaped at his feet (or a location of his choice) for his poetic translation):

The nucleus of the narrative centres on the misfortunes of Macabéa, a humble girl from a region plagued by drought and poverty, whose future is determined by her inexperience, her ugliness and her total anonymity. Macabéa’s speech and dress betray her origins. An orphaned child from the backwoods of Alagoas, who was brought up by the forbidding aunt in Maceió before making her way to the slums of Acre Street in the heart of Rio de Janeiro’s red-light district. Gauche and rachitic, Macabéa has poverty and ill-health written all over her: a creature conditioned from birth and already singled out as one of the world’s inevitable losers.

Her humdrum existence can be summarized in few words: Macabéa is an appallingly bad typist, she is a virgin, and her favorite drink is Coca-Cola. She is a perfect foil for a bullying employer, a philandering boy friend, and her workmate Glória, who has all the attributes Macabéa sadly lacks.

12. A dozen things that The Hour of the Star may or may not be about: Poverty, storytelling, lies, illusions, abjection, resistance, agency, self, class, power, romance, fate.

13. But let’s get back to those words the narrator is braggin’ on:

Another angle at approaching The Hour of the Star: Its page of thirteen alternate titles, which act as a prose-poem descriptor for the novella:

14. And some sentences:

The first provides a context. The second tells us everything about Macabéa. The third tells us everything about her awful, venal “boy friend” Olímpico:

For quite different reasons they had wandered into a butcher’s shop. Macabéa only had to smell raw meat in order to convince herself that she had eaten. What attracted Olímpico, on the other hand, was the sight of a butcher at work with his sharp knife.

15. Macabéa, our primary, and Olímpico a distant second. But also Rodrigo S.M. (and a few others):

The story—I have decided with an illusion of free will—should have some seven characters, and obviously I am one of the more important.

16. (Again though, how to parse Rodrigo from Clarice Lispector . . .)

17. So maybe in one of his (her) parenthetical intrusions (but how can they be intrusions?). From late in the novella:

(But what about me? Here I am telling a story about events that have never happened to me or to anyone known to me. I am amazed at my own perception of the truth. Can it be that it’s my painful task to perceive in the flesh truths that no one wants to face? If I know almost everything about Macabéa, it’s because I once caught a glimpse of this girl with the sallow complexion from the North-east. Her expression revealed everything about her . . .)

Solipsism? Hubris? Humor? Irony?

Truth?

18. But I want to say something about how funny this novella, but I don’t know how to say it, or I’m not sure how to illustrate it, how to support such a claim with text—how does one support a feeling, a vibe, a phantom idea? Is The Hour of the Star actually funny? Or am I a sick man? Why did I chuckle so much?

19. I think, re: 18, I think that it must be a mild streak of sadism, or an identification with the narrator’s flawed empathy, his raw presentation of a pathetic, abject heroine, a heroine whose heroism can only manifests in strange eruptions of self-possession, minor triumphs of the barest self-assertions.

20. Perhaps an illustration, re: 18/19—a lengthy one maybe, but indulge me (or, rather, indulge yourself):

At this point, I must record one happy event. One distressing Sunday without mandioca, the girl experienced a strange happiness: at the quayside, she saw a rainbow. She felt something close to ecstasy and tried to retain the vision: if only she could see once more the display of fireworks she had seen as a child in Maceió. She wanted more, for it is true that when one extends a helping hand to the lower orders, they want everything else.; the man on the street dreams greedily of having everything. He has no right to anything but he wants everything. Wouldn’t you agree? There were no means within my power to produce that golden rain achieved with fireworks.

Should I divulge that she adored soldiers? She was mad about them. Whenever she caught sight of a soldier, she would think, trembling with excitement: is he going to murder me?

Can you feel the shifts here? A distressing Sunday, a hungry Sunday (“without mandioca”); its strange happiness; an ecstasy that repeats a childhood vision; the desire for more, to rise above one’s allotment (The Right to Protest, or, She Doesn’t Know How to Protest); the limits of words, of language. An unexpected, seemingly irrelevant anecdote. A rare dip into our heroine’s consciousness.

21. There’s a certain absurdity here, a methodical absurdity, of course. There’s a rhythmic certainty to the prose—a sense of aesthetic uniformity—but the content jars against it, the meaning spikes out in subtly incongruous jags that form some other shape. Folks say folks say Lispector echoes Kafka in this way. (I’m reminded of Robert Walser’s sentences too).

22. But I’ve shared enough to give you a sense of Lispector’s style, a taste anyway, right?

What about the book’s claim, its viewpoint, its thesis?

23. Okay, so it’s right there upfront in the book’s fifth paragraph, delivered early enough when the reader is suitably perplexed, looking for some kind of narrative inroad, not looking necessarily for a theme or a message or what have you:

Even as I write this I feel ashamed at pouncing on you with a narrative that is so open and explicit. A narrative, however from which blood surging with life might flow only to coagulate into lumps of trembling jelly. Will this story become my own coagulation one day? Who can tell? If there is any truth in it—and clearly the story is true even though invented—let everyone see it reflected in himself for we are all one and the same person . . .

24. Let’s not misunderstand the last sentiment as some hippy-dippy bullshit: Let’s go back to: “I must touch the invisible in its own squalor.”

25. That squalor is the abject, the filth, the not-me, the other, signified most strongly in waste, blood, filth, vomit, the corpse.

26. The gesture of The Hour of the Star is to make visible—in sentences, in words, in language—the invisible in its own squalor.

27. Highly recommended.

Book shelves series #17, seventeenth Sunday of 2012.

Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Steinbeck, Camus, Nabokov, Celine, Kafka.

Jonathan Littell’s The Kindly Ones with Revere movie camera as bookend. Littell’s lurid, bizarre book is only shelved here temporarily (he’s in too-rarefied company, perhaps).

A friend gave me this in high school.

Lars Iyer’s novel (or anti-novel, if you swing that way) Spurious was one of the better books I read last year. From my review:

Lars Iyer’s début novel Spurious is about two would-be intellectuals, W., the book’s comic hero, and his closest friend, our narrator Lars. They bitch and moan and despair: it’s the end of the world, it’s the apocalypse; they find themselves incapable of original thought, of producing any good writing. The shadow of Kafka paralyzes them. They travel about Europe, seeking out knowledge and inspiration — or at least a glimpse of some beautiful first editions of Rosenzweig. They attend dreadful academic conferences; they write letters. They flounder and fail.

Iyer was also kind enough to talk with me in a long, detailed interview.

So like basically I’m a fan, and I’ve been eager for Dogma, so I was psyched when an ARC showed up in Monday’s mail. Dogma is new from Melville House at the end of this month; more coverage to come.

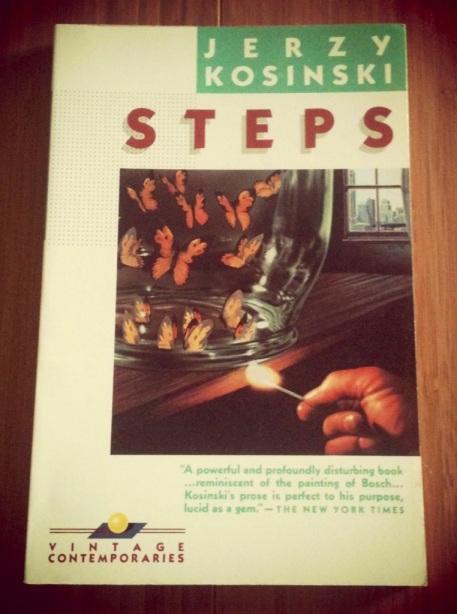

One of the many small vignettes that comprise Jerzy Kosinski’s 1968 book Steps begins with the narrator going to a zoo to see an octopus that is slowly killing itself by consuming its own tentacles. The piece ends with the same narrator discovering that a woman he’s picked up off the street is actually a man. In between, he experiences sexual frustration with a rich married woman. The piece is less than three pages long.

There’s force and vitality and horror in Steps, all compressed into lucid, compact little scenes. In terms of plot, some scenes connect to others, while most don’t. The book is unified by its themes of repression and alienation, its economy of rhythm, and, most especially, the consistent tone of its narrator. In the end, it doesn’t matter if it’s the same man relating all of these strange experiences because the way he relates them links them and enlarges them. At a remove, Steps is probably about a Polish man’s difficulties under the harsh Soviet regime at home played against his experiences as a new immigrant to the United States and its bizarre codes of capitalism. But this summary is pale against the sinister light of Kosinski’s prose. Consider the vignette at the top of the review, which begins with an autophagous octopus and ends with a transvestite. In the world of Steps, these are not wacky or even grotesque details, trotted out for ironic bemusement; no, they’re grim bits of sadness and horror. At the outset of another vignette, a man is pinned down while his girlfriend is gang-raped. In time he begins to resent her, and then to treat her as an object–literally–forcing other objects upon her. The vignette ends at a drunken party with the girlfriend carried away by a half dozen party guests who will likely ravage her. The narrator simply leaves. Another scene illuminates the mind of an architect who designed concentration camps. “Rats have to be removed,” one speaker says to another. “Rats aren’t murdered–we get rid of them; or, to use a better word, they are eliminated; this act of elimination is empty of all meaning. There’s no ritual in it, no symbolism. That’s why in the concentration camps my friend designed, the victim never remained individuals; they became as identical as rats. They existed only to be killed.” In another vignette, a man discovers a woman locked in a metal cage inside a barn. He alerts the authorities, but only after a sinister thought — “It occurred to me that we were alone in the barn and that she was totally defenseless. . . . I thought there was something very tempting in this situation, where one could become completely oneself with another human being.” But the woman in the cage is insane; she can’t acknowledge the absolute identification that the narrator desires. These scenes of violence, control, power, and alienation repeat throughout Steps, all underpinned by the narrator’s extreme wish to connect and communicate with another. Even when he’s asphyxiating butterflies or throwing bottles at an old man, he wishes for some attainment of beauty, some conjunction of human understanding–even if its coded in fear and pain.

In his New York Times review of Steps, Hugh Kenner rightly compared it to Céline and Kafka. It’s not just the isolation and anxiety, but also the concrete prose, the lucidity of narrative, the cohesion of what should be utterly surreal into grim reality. And there’s the humor too–shocking at times, usually mean, proof of humanity, but also at the expense of humanity. David Foster Wallace also compared Steps to Kafka in his semi-famous write-up for Salon, “Five direly underappreciated U.S. novels > 1960.” Here’s Wallace: “Steps gets called a novel but it is really a collection of unbelievably creepy little allegorical tableaux done in a terse elegant voice that’s like nothing else anywhere ever. Only Kafka’s fragments get anywhere close to where Kosinski goes in this book, which is better than everything else he ever did combined.” Where Kosinski goes in this book, of course, is not for everyone. There’s no obvious moral or aesthetic instruction here; no conventional plot; no character arcs to behold–not even character names, for that matter. Even the rewards of Steps are likely to be couched in what we generally regard as negative language: the book is disturbing, upsetting, shocking. But isn’t that why we read? To be moved, to have our patterns disrupted–fried even? Steps goes to places that many will not wish to venture, but that’s their loss. Very highly recommended.

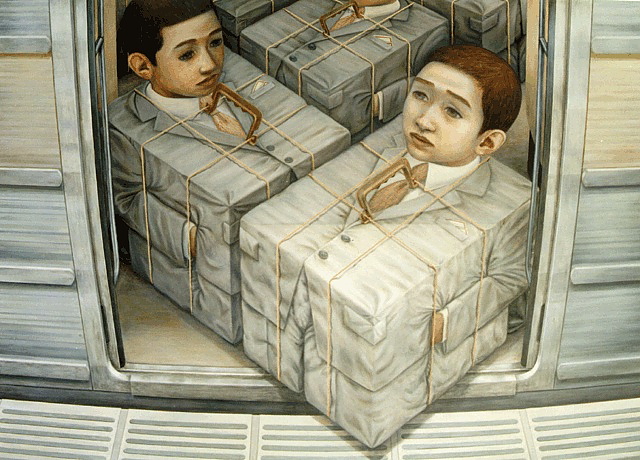

I’m enamored with a set of paintings by Japanese artist Tetsuya Ishida that has floated around the internet lately. (See iterations here, here, and here). Ishida’s paintings depict young, sad Japanese people who have transformed into (or always were?) banal objects or insect-like animals. Ishida’s figures are often constrained into claustrophobic spaces, with pained expressions evincing despair and anxiety. There’s a paradoxical loneliness in his works as well: his protagonists are often surrounded by others who have also metamorphosed into machine-like beings, automatons performing sinister operations on the protagonists.

Ishida’s themes of the salaryman’s despair at the strictures of a modernized, hyper-industrialized society where conformity is prized are distinctly Japanese, but they also resonate beyond that culture. They are Kafkaesque, tapping into the alienation that the individual faces in an increasingly absurd, bureaucratic, mechanized world that turns people into cogs, bugs, things. Ishida was killed when he was hit by a train in 2005–his death was likely a suicide.

In both subject and stylistic execution, Ishida’s work is reminiscent of American artist George Tooker‘s paintings of the alienation and anxieties produced by urban bureaucracy.

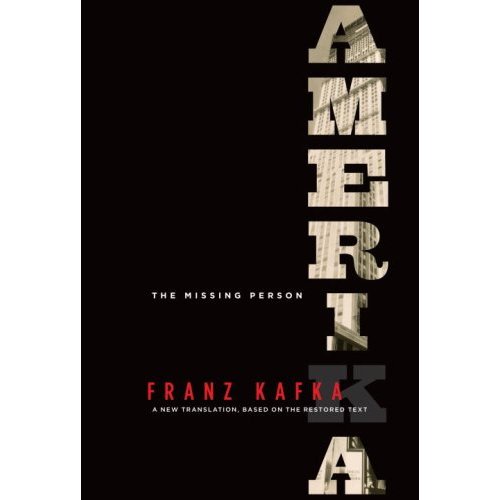

I had a (very, very minor) Kafkaesque moment when Mark Harman’s new translation of Franz Kafka’s unfinished first novel, Amerika first arrived at Biblioklept International Headquarters. Wanting to compare the style of Harman’s translation to Edwin and Willa Muir’s work, I searched for my old copy of Amerika. I figured I’d re-read the first chapter, “The Stoker,” the only part of the novel that Kafka reworked (it was published as a short story). So I looked and looked and it turns out that I don’t own Amerika, despite the obligatory Kafka phase I went through in high school (followed by a post-bac Kafka phase years later). But I knew I’d read “The Stoker,” or at least it seemed likely that I’d read “The Stoker,” and it turned up in a collection of Kafka’s short stories that I own–only it was the Donna Freed translation. So I re-read it, only I’m not sure that I was re-reading it. I didn’t remember any of it, other than the famous opening image of a Statue of Liberty armed with a sword. I’m still not sure that I ever read it before now; that is, I’m not sure that I read the Muir translation that Harman seeks to amend. I guess it doesn’t matter, and it seems appropriate that a Kafka review begin with a meandering false start. Where were we?

Yes. Harman’s translation. With Amerika, Harman continues a project he initiated with his translation of another unfinished Kafka novel, The Castle. (This book was published in 1998, and I listened to the audio book last summer, incidentally, and it was really, really good). Harman’s translations aim to restore some of the humor, ambiguity, and modernism that the Muirs’ early translations occlude in favor of their own religious readings. Harman also takes great pains to remove Max Brod’s editorial interventions, even going as far as to keep many of Kafka’s consistent solecisms (“Oklahoma” is restored to Kafka’s original – and consistent – “Oklahama”). Now, my Kafkaesque confusion over whether or not I’ve read the Muirs’ translation of Amerika prevents me from commenting here on Harman’s apparent restoration of Kafka’s humor, but I do think that Amerika is often funny, and often terrifying. Its protagonist Karl finds himself in a parallel-universe America (one constructed wholly from Kafka’s imagination, and announced in its surreal glory from the opening image of a Statue of Liberty armed with sword), one where he’s consistently misled, swindled, cornered, cramped, and generally mistreated by various enigmatic authority figures (yes, its Kafkaesque, if you’ll allow the tautology). As noted, Kafka never finished writing the book (or any of his three novels, for that matter), and Harman makes no attempt to reconcile the plot, opting instead to simply reproduce (in frank English, of course) the words Kafka wrote.

Amerika is not the starting place for those new to Kafka’s work–I would suggest readers who weren’t turned off by their high school English teacher’s inept bungling of The Metamorphosis start with a collection of the short stories. However, I think Harman’s translation is not only essential for fans who wish to rediscover an old favorite, I also believe that it will quickly become the definitive translation. It’s modern and terse and funny, and it also pays subtle respect to the dialogic interplay between Karl’s point of view and that of the omniscient narrator, often creating moments of intense and delicious irony. Reading a translation of Kafka focusing on his oft-neglected humor brought to mind the late great David Foster Wallace’s essay, “A Series of Remarks on the Funniness of Kafka, from Which Not Enough Has Been Removed” (read it here or get the mp3 of DFW reading it here). Here is Wallace, explaining why American undergrads don’t get Kafka’s humor:

And it is this, I think, that makes Kafka’s wit inaccessible to children whom our culture has trained to see jokes as entertainment and entertainment as reassurance. It’s not that students don’t “get” Kafka’s humor but that we’ve taught them to see humor as something you get — the same way we’ve taught them that a self is something you just have. No wonder they cannot appreciate the really central Kafka joke — that the horrific struggle to establish a human self results in a self whose humanity is inseparable from that horrific struggle. That our endless and impossible journey toward home is in fact our home.

Wallace’s observation stealthily acknowledges why the heroes of Amerika and The Trial and The Castle never get to where they’re going, why Kafka could never wrap up his big stories. Kafka, the first modern writer, embraced the “horrific struggle” of humanity and never sought easy reconciliation or pat conclusions. Harman’s new translation brings this critical aspect of Kafka’s writing to the fore, and he achieves this in the most simplistic manner: unobtrusively letting Kafka’s words stand on their own. Recommended.

Amerika is now available from Schocken Books.