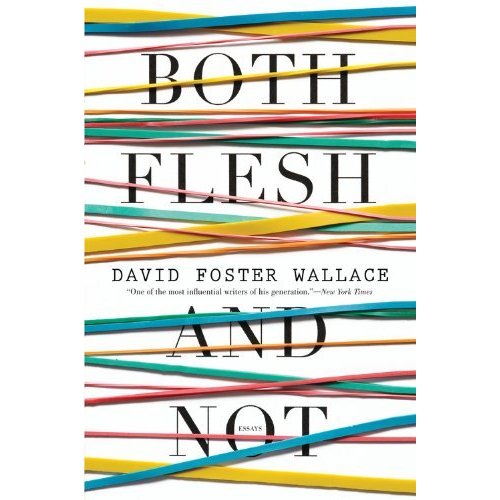

In an interview published back in 2010 (coinciding roughly with the release of his excellent novel C), Tom McCarthy evaluated his work:

I see what I’m doing as simply plugging literature into other literature. For me, that’s what literature’s always done. If Shakespeare finds a good speech in an older version of Macbeth or Pliny, he just rips it and mixes it. It’s like DJing.

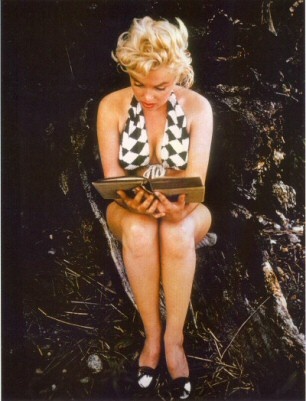

McCarthy’s new essay “Transmission and the Individual Remix” explores the idea of artist as DJ, as remixer, as synthesizer. It’s a brief, fun read—28 pages on paper the publicity materials claim, but it’s only available as an etext, so its length is hard to measure in terms of pages. It took me less than an hour to read it on my Kindle Fire. Then I read it again. Although publisher Vintage kindly sent me a copy, I’d argue that it’s well worth the two bucks they’re asking.

“Transmission” is playful and discursive, as befits its subject. The essay is not nearly as pretentious as its subtitle (“How Literature Works”) might suggest. McCarthy riffs on a few subjects to illustrate his thesis: Kraftwerk, the Orpheus myth (and its many, many retellings and interpretations), Rilke, Alexander Graham Bell, “Blanchot, Barthes, or any other dubious French character whose names starts with B,” Ulysses, Kafka, Beckett, etc. But what is his thesis? What does he want? He tells us:

My aim here, in this essay, is not to tell you something, but to make you listen: not to me, nor Beckett and Kafka, but to a set of signals that have been repeating, pulsing, modulating in the airspace of the novel, poem, play—in their lines, between them and around them—since each of these forms began. I want to make you listen to them, in the hope not that they’ll deliver up some hidden and decisive message, but rather that they’ll help attune your ear to the very pitch and frequency of its own activity—in other words, that they’ll help attune your ear to the very pitch and frequency of its own activity—in other words, that they’ll enable you to listen in on listening itself.

McCarthy’s concern here is to point out that nothing is original, that all creation is necessarily an act of synthesis. To read a novel is to read through the novel, to read the novelist’s sources (or, to use McCarthy’s metaphor, to listen through). McCarthy’s insights here are hardly new, of course—Ecclesiastes 1:19 gives us the idea over 2000 years ago, and surely it’s just another transmitter passing on a signal. What makes “Transmission” such a pleasure is its frankness, its clarity. Unlike so much postmodern criticism, McCarthy doesn’t trip over jargon or take flights of fancy into obscure metaphor. And even when he does get a bit flighty, he manages to clarify so many ideas of basic deconstructive theory:

This is it, in a nutshell: how writing works. The scattering, the loss; the charge coming from somewhere else, some point forever beyond reach or even designation, across a space of longing; the surge; coherence that’s only made possible by incoherence; the receiving which is replay, repetition—backward, forward, inside out or upside down, it doesn’t matter. The twentieth century’s best novelist understood this perfectly. That’s why Ulysses’s Stephen Dedalus—a writer in a gestational state of permanent becoming—paces the beach at Sandymount mutating, through their modulating repetition, air- and wave-borne phrases he’s picked up from elsewhere, his own cheeks and jaw transformed into a rubbery receiver . . .

Amazingly, the name Derrida doesn’t show up in “Transmission,” even as McCarthy gives us such a clear outline of that philosopher’s major ideas, as in the above riff’s explication of différance and iterability (with twist of Lacanian lack to boot). Or here, where McCarthy deconstructs the notion of a stable self:

All writing is conceptual; it’s just that it’s usually founded on bad concepts. When an author tells you that they’re not beholden to any theory, what they usually mean is that their thinking and their work defaults, without even realizing it, to a narrow liberal humanism and its underlying—and always reactionary—notions of the (always “natural” and preexisting, rather than constructed self, that self’s command of language, language as vehicle for “expression,” and a whole host of fallacies so admirably debunked almost fifty years ago by the novelist Alain Robbe-Grillet.

So I read Derrida through McCarthy’s reading of Robbe-Grillet. This is all transmission, writing as remix, but also reading as remix.

I could go on, but I fear that I’ll simply start citing big chunks of McCarthy’s essay, which is supremely citable, wonderfully iterable. Recommended.