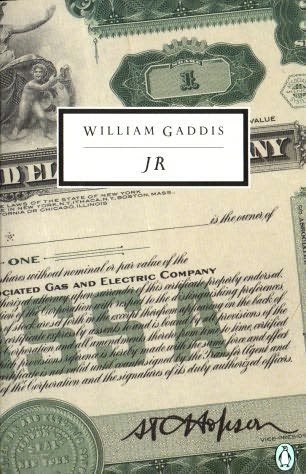

1. I want to write about William Gaddis’s novel J R, which I am about half way through now.

2. I’ve been listening to the audiobook version, read with operatic aplomb by Nick Sullivan. I’ve also been rereading bits here and there in my trade paperback copy.

3. What is J R about? Money. Capitalism. Art. Education. Desperate people. America.

4. The question posed in #3 is a fair question, but probably not the right question, or at least not the right first question about J R. Instead—What is the form of J R—How is J R?

5. A simple answer is that the novel is almost entirely dialog, usually unattributed (although made clear once one learns the reading rules for J R). These episodes of dialogue are couched in brief, pristine, precise, concrete—yet poetic—descriptions of setting. Otherwise, no exposition. Reminiscent of a movie script, almost.

6. A more complex answer: J R, overstuffed with voices, characters (shadows and doubles), and motifs, is an opera, or a riff on an opera, at least.

7. A few of the motifs in J R: paper, shoes, opera, T.V. equipment, entropy, chaos, novels, failure, frustration, mechanization, noise, hunting, war, music, commercials, trains, eruptions of nonconformity, advertising, the rotten shallowness of modern life . . .

8. Okay, so maybe that list of motifs dipped into themes. It’s certainly incomplete (but my reading of J R is incomplete, so . . .)

9. Well hang on so what’s it about? What happens?—This is a hard question to answer even though there are plenty of concrete answers. A little more riffage then—

10. Our eponymous hero, snot-nosed JR (of the sixth grade) amasses a paper fortune by trading cheap stocks. He does this from a payphone (that he engineers to have installed!) in school.

11. JR’s unwilling agent—his emissary into the adult world—is Edward Bast, a struggling young composer who is fired from his teaching position at JR’s school after going (quite literally) off script during a lesson.

12. Echoes of Bast: Thomas Eigen, struggling writer. Jack Gibbs, struggling writer human. Gibbs, a frustrated, exasperated, alcoholic intellectual is perhaps the soul of the book. (Or at least my favorite character).

13. Characters in J R tend to be frustrated or oblivious. The oblivious characters tend to be rich and powerful; the frustrated tend to be artistic and intellectual.

14. Hence, satire: J R is very, very funny.

15. J R was published over 35 years ago, but its take on Wall Street, greed, the mechanization of education, the marginalization of art in society, and the increasing anti-intellectualism in America is more relevant than ever.

16. So, even when J R is funny, it’s also deeply sad.

17. Occasionally, there’s a histrionic pitch to Gaddis’s dialog: his frustrated people, in their frustrated marriages and frustrated jobs, explode. But J R is an opera, I suppose, and we might come to accept histrionics in an opera.

18. Young JR is a fascinating study, an innocent of sorts who attempts to navigate the ridiculous rules of his society. He is immature; he lacks human experience (he’s only 11, after all), and, like most young children, lacks empathy or foresight. He’s the perfect predatory capitalist.

19. All the love (whether familial or romantic or sexual) in J R (thus far, anyway) is frustrated, blocked, barred, delayed, interrupted . . .

20. I’m particularly fascinated by the scenes in JR’s school, particularly the ones involving Principal Whiteback, who, in addition to his educational duties, is also president of a local bank. Whiteback is a consummate yes man; he babbles out in an unending stammer of doubletalk; he’s a fount of delicious ironic humor. Sadly though, he’s also absolutely real, the kind of educational administrator who thinks a school should be run like a corporation.

21. The middlebrow novelist Jonathan Franzen, who has the unlikely and undeserved reputation of being a literary genius, famously called Gaddis “Mr. Difficult” (in an essay of the same name).

22. Franzen’s essay is interesting and instructive though flawed (he couldn’t make it through the second half of J R). From the essay:

“J R” is written for the active reader. You’re well advised to carry a pencil with which to flag plot points and draw flow charts on the inside back cover. The novel is a welter of dozens of interconnecting scams, deals, seductions, extortions, and betrayals. Between scenes, when the dialogue yields briefly to run-on sentences whose effect is like a blurry handheld video or a speeded-up movie, the images that flash by are of denatured, commercialized landscapes — trees being felled, fields paved over, roads widened — that recall to the modern reader how aesthetically shocking postwar automotive America must have been, how dismaying and portentous the first strip malls, the first five-acre parking lots.

23. Franzen, of course, is not heir to Gaddis. If there is one (and there doesn’t need to be, but still), it’s David Foster Wallace. Reading J R I am constantly reminded of Wallace’s work.

24. But also Joyce. J R is thoroughly Joycean, at least in its formal aspects: that friction between the deteriorated language of commerce and the high aims of art; the sense and sound and rhythms of the street. (Is there a character more frustrated in Western literature than Stephen Dedalus? Surely he finds some heirs in Gibbs, Bast, and Eigen . . .)

25. Gaddis denied (or at least deflected) a Joycean influence. Better to say then that they were both writing the 20th century, only from different ends of said century.

26. And then a question for navel-gazing lit major types, a question of little import, perhaps a meaningless question (certainly a dull one for most decent folks): Is J R late modernism or postmodernism? Late-late modernism?

27. Gaddis shows a touch of the nameyphilia that we see (out of control) in Pynchon: Hence, Miss Flesch, Father Haight, the diCephalis family, Nurse Waddams, Stella Angel, Major Hyde, etc.

28. To return to the plot, or the non-plot, of J R: As I’ve said, I’m only half way through the thing, but I can’t see its shape. That sentence might need a “yet” at the end; or, J R might be so much chaos.

29. In any case, I will report again at the end, if not sooner.