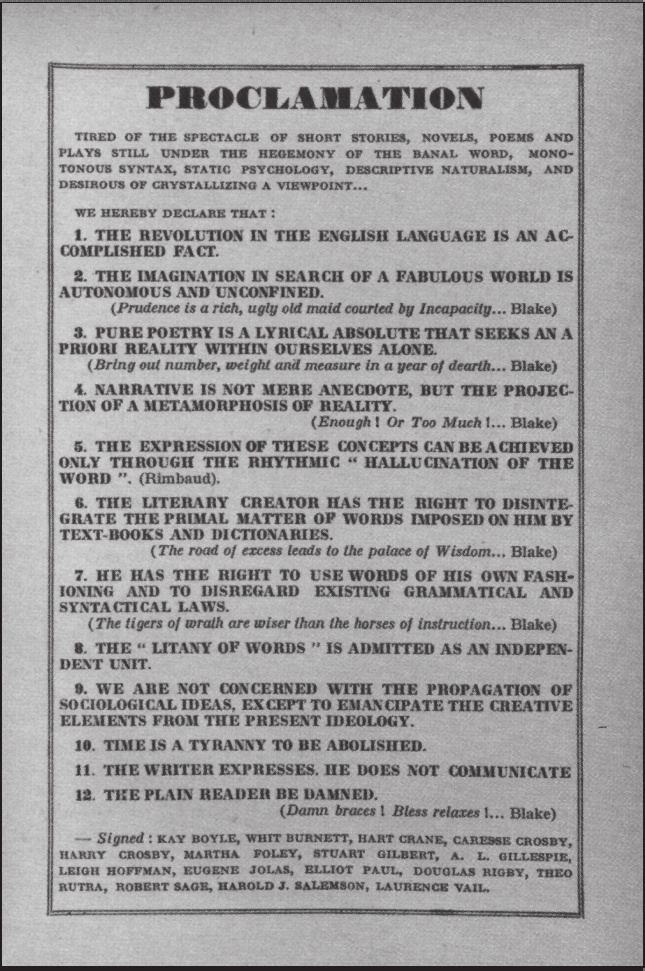

I’ve been digging Stephen Eric Bronner’s tight synthesis of modernism, Modernism at the Barricades, which traces the historical rise of expressionism, futurism, surrealism and more against the political, social, and historical backdrop of the emerging 20th century. Bronner’s book is a sharp but concise primer of sorts, using examples like the correspondence between Schoenberg and Kandinsky and the paintings of Emil Nolde to illuminate the big concepts and cultural aims of different modernist movements. Photographs, prints, and posters (like the proclamation below) help to illustrate Bronner’s chapters as well.

Bronner’s book would make a handy starting point to any student beginning a study of modernism. It doesn’t try to exhaustively account for each and every modernist, but neither does it forsake specificity in favor of a broad overview. Best of all, Bronner is clear and concise, an attribute which unfortunately is all too rare in academic writing. There’s a lucid sensibility that seems to govern the book, which we can see from its earliest chapter. Here Bronner delineates modernism’s cultural project and at the same time points out some of modernism’s own shortsightedness:

Modernism would call into question every aspect of modern life, from the architecture through which our apartments are designed, to the furniture in which we sit, to the comic books our children read, to the films we watch and the museums we visit, to the experience of time and individual possibility that mark our lives. Modernists may have believed that they were contesting modernity, but their efforts and their hopes were shaped by it. Their activities legitimated what they intended to oppose. Their critique, in short, presupposed its object. Modernists believed that they were contesting tradition in the name of the new and the constraints of everyday life in the name of multiplied experience and individual freedom. These artists were essentially anarchists imbued with what Georg Lukács termed “romantic anti-capitalism.”

They opposed the “system” without understanding how it worked or what radical political transformation required and implied. Oddly, they never understood how deeply they were enmeshed in what they opposed. Modernists envisioned an apocalypse that had no place for institutions or agents generated within modernity. Theirs was less a concern with class consciousness than an opposition to the alienating and reifying constraints of modernity. Unfettered freedom of expression and a transformation in the experience of everyday life were the modernists’ goals. Even when seduced by totalitarian movements, whether of the left or the right, most of them despised what Czeslaw Milosz called the“captive mind.” Not all the problems that they uncovered—sexual repression and generational conflicts, among others—required utopian solutions. But their utopian inclinations were transparent from the beginning. Modernists believed that the new would not come from within modernity, but would appear as an external event or force for which, culturally, the vanguard would act as a catalyst.

Good stuff. Modernism at the Barricades is new in hardback from Columbia University Press.