The bird called bustard flies away at the sight of a horse, and a hart runs away at the sight of a ram, as also of a viper.

An elephant trembles at the hearing of the grunting of a hog, so doth a lion at the sight of a cock; and panthers will not touch them that are anointed all over with the broth of a hen, especially if garlic hath been boiled in it.

There is also enmity betwixt foxes and swans, bulls and jackdaws.

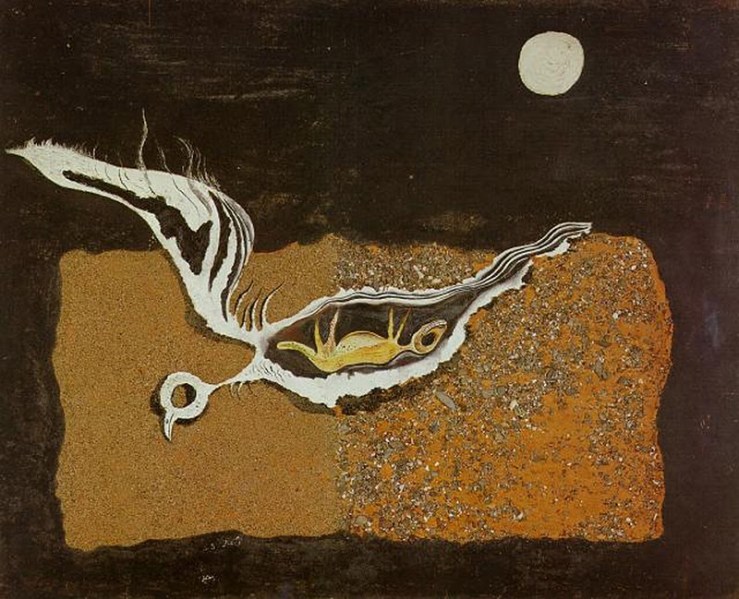

Amongst birds, also, some are at perpetual strife one with another, as also with other animals, as jackdaws and owls, the kite and crows, the turtle and ring-tail, egepis and eagles, harts and dragons.

Also amongst water animals there is enmity, as betwixt dolphins and whirlpools, mullets and pikes, lampreys and congers.

Also the fish called pourcontrel makes the lobster so much afraid that the lobster, seeing the other but near him, is struck dead.

The lobster and conger tear one the other.

The civet cat is said to stand so in awe of the panther that he hath no power to resist him or touch his skin; and they say that if the skins of both of them be hanged up one against the other, the hairs of the panther’s skin fall off.

And Orus Apollo saith in his hieroglyphics, if any one be girt about with the skin of the civet cat that he may pass safely through the middle of his enemies and not at all be afraid.

Also the lamb is very much afraid of the wolf and flies from him. And they say that if the tail or skin or head of a wolf be hanged upon the sheep-coate the sheep are much troubled and cannot eat their meat for fear.

And Pliny makes mention of a bird, called marlin, that breaks crows’ eggs, whose young are so annoyed by the fox that she also will pinch and pull the fox’s whelps, and the fox herself also; which when the crows see, they help the fox against her, as against a common enemy.

The little bird called a linnet, living in thistles, hates asses, because they eat the flowers of thistles.

Also there is such a bitter enmity betwixt the little bird called esalon and the ass that their blood will not mix together, and that at the braying of the ass both the eggs and young of the esalon perish.

There is also such a disagreement betwixt the olive-tree and a wanton, that if she plant it, it will either be always unfruitful or altogether wither.

A lion fears nothing so much as fired torches, and will be tamed by nothing so much as by these; and the wolf fears neither sword nor spear, but a stone—by the throwing of which, a wound being made, worms breed in the wolf.

A horse fears a camel so that he cannot endure to see so much as his picture.

An elephant, when he rageth, is quieted by seeing of a cock.

A snake is afraid of a man that is naked, but pursues a man that is clothed.

A mad bull is tamed by being tied to a fig-tree.

(NB: I took the editorial liberty of turning Agrippa’s marvelous paragraphs into a list, which I think reads a bit better, or at least more absurdly).