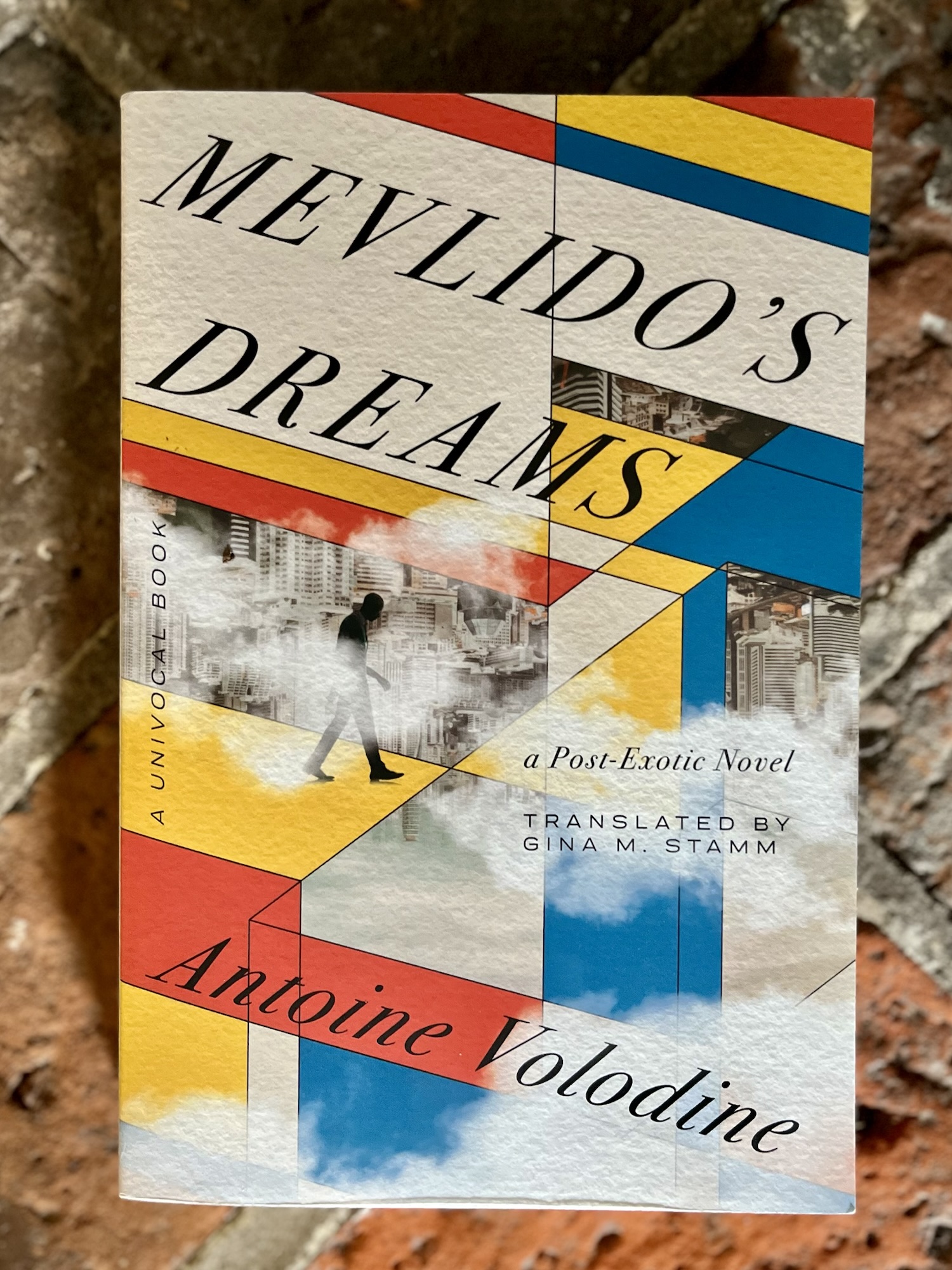

Let’s start with the epigraph:

“Supernatural, perhaps. Baloney…perhaps not.”

—Bela Lugosi,

in The Black Cat (1934)

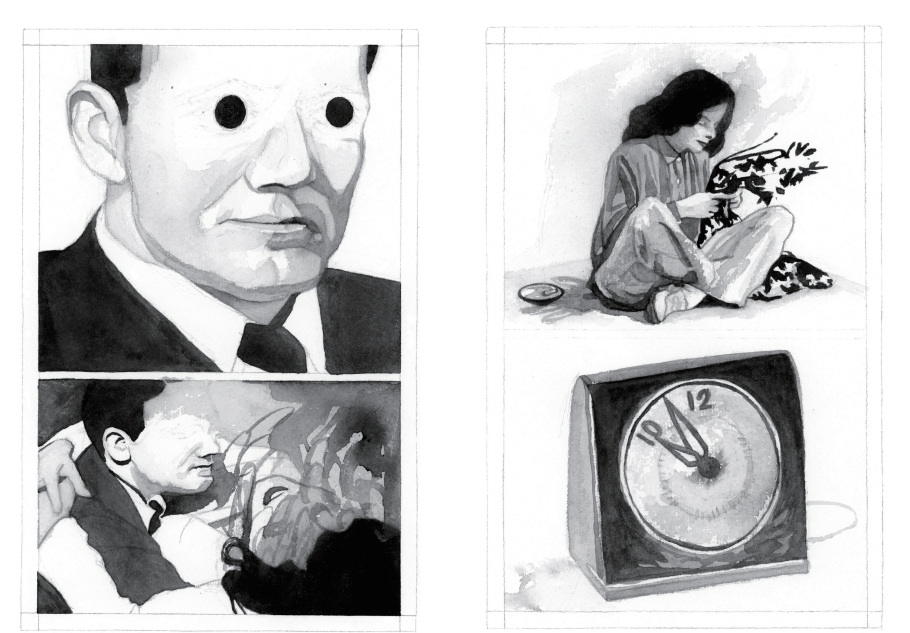

Dr. Vitus Werdegast, Bela Lugosi’s character in The Black Cat, gives this line to mystery novelist Peter Alison (portrayed by David Manners). Here is the scene:

Pynchon is not the first to sample this line.

The epigraph for Shadow Ticket highlights a concern with the metaphysical that Pynchon has shown throughout his novels. The epigraph encapsulates this concern, ties it to the talkies, the American Gothic tradition, and wedges in a slice of absurd (and drily-delivered) humor early on.

Chapter 1; the novel’s first line:

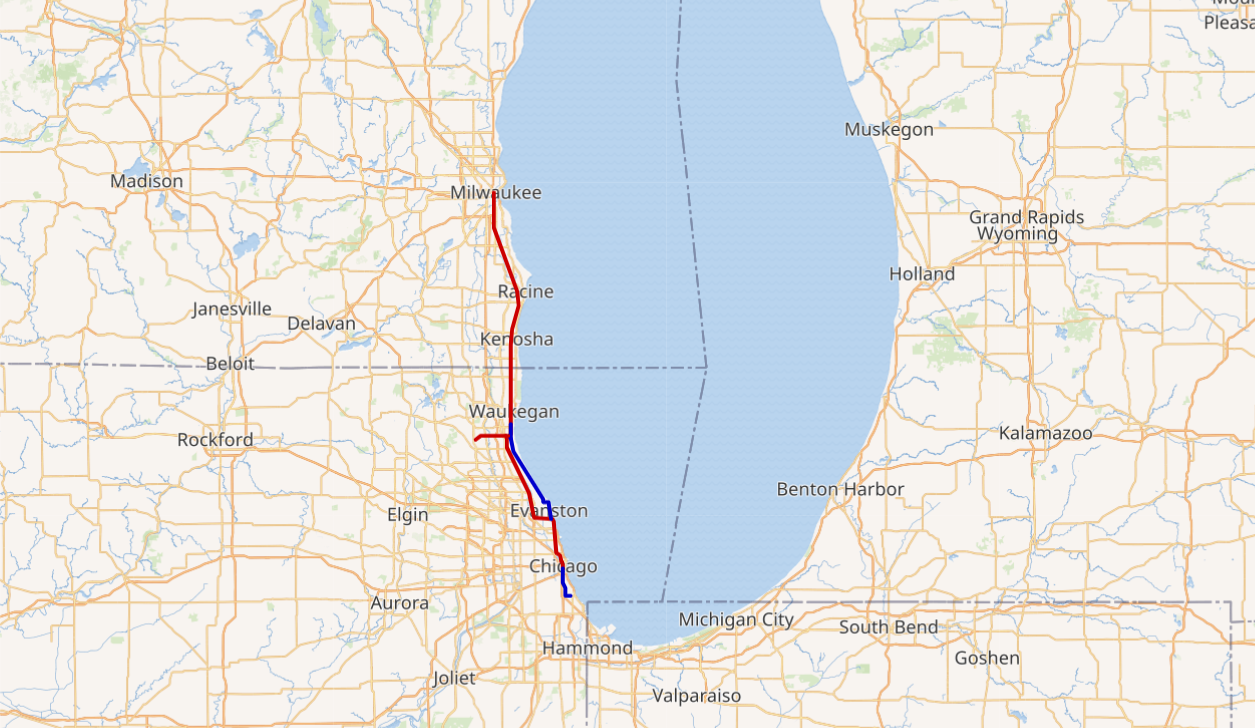

“When trouble comes to town, it usually takes the North Shore Line.”

Shadow Ticket is set, thus far and for the most part, in Milwaukee Wisconsin in early 1931. For about half a century, The Chicago North Shore and Milwaukee Railroad ran from Chicago to Milwaukee, roughly a long the coast of Lake Michigan. It ceased operations in early 1963.

(Even went through Kenosha, kid.)

The opening paragraphs introduce us to Shadow Ticket’s hero Hicks McTaggart and establish a snappy, hardboiled style reminiscent of films of the thirties and forties (or films of the Coen Brothers that pay homage to those films).

“Everybody is looking at everybody else like they’re all in on something. Beyond familiarity or indifference, some deep mischief is at work.”

These lines append the postprandial scene of a noontime explosion. We get paranoia and a whiff of the supernatural — that “deep mischief…at work.”

“Pineapples come and pineapples go,” declares Hicks’s boss Boynt Crosstown, dismissing the explosion. (Perhaps the name Boynt Crosstown evokes “Burnt Cross Town”?)

Pineapples, slang for grenades specifically or explosives more generally, pops up repeatedly early on in Shadow Ticket.

“…local multimillionaire Bruno Airmont, known throughout the dairy industry as the Al Capone of Cheese in Exile…this one’s more about his daughter Daphne…Seems your old romance has just run off with a clarinet player in a swing band.”

Daphne Airmont, Runaway Cheese Heiress: an early MacGuffin or possible red herring to look out for. One of many, many of Pynchon’s female characters on the run.

(Parenthetically, I suppose, because it’s of such minor note, but there’s a mention of one “Zbig Dubinsky” — surely, Shirley, a minor character? — but the name seems to echo the Coens’ film The Big Lebowski.)

“Getting sentimental, kid, better watch ’at, once.”

A warning from Hicks to his protege Skeet Wheeler, a “flyweight juvenile in a porkpie hat.” We’ll see more of Skeet’s apparent sentimentality when he pockets a ball bearing from an exploded REO Speed Wagon. The line would be a throwaway for me, except that it is the first instance of the word kid in the novel. We see it pop up frequently in several forms, including kidding and kiddies. In Ch. 1, Skeet refers to his “snub nose service .32″ pistol as a “Kids’ Special.” We learn that Skeet is tapped into the “kid underworld—drifters, truants, and guttersnipes, newsboys at every corner and streetcar stop—who in turn have antennas of their own out.” The system of littler kids reporting to bigger kids, etc., reports Skeet to bigger kid Hicks, is “like Mussolini.” (Hitler will show up soon.)

“‘…New watch, I see.’

‘Hamilton, glows in the dark too.'”

The first of (by my count) four specific references to things that glow in the dark. I’ll remark on them in turn, but the other three are Hicks’s hair gel (Ch. 3), a jello salad served at the Velocity Lunch diner (Ch. 5), and a pair of novelty vampire fangs (Ch. 7).

In Pynchon’s books, and in particular in Against the Day and Mason & Dixon, there is a concern with the invisible world, which might be taken as the metaphysical world, or, the supernatural-but-not-baloney world. Perhaps these novelties that glow in the dark point in that direction?

Chapter 2 begins at the crime scene, the scene of an exploded bootlegger’s hoochwagon (the aforementioned REO Speed Wagon).

The “kid” motif develops with references to “Federal kiddies that nobody’s ever heard of,” “Chicago Latin kids,“ and “German storm kiddies.“ A page or two later soda jerk Hoagie Hivnak (of a certain “adenoidal brashness”) laments that his Ideal Pharmacy “was no place for kids, the words ‘soda fountain’ would send mothers all over town into fits, worse than ‘opium den.'” No more coke in the sodas for the “Leapers and sleigh riders” to enjoy.

Hoagie moves the plot forward, telling Hicks to “Track down Bruno Airmont wherever he’s got to.”

Chapter 3: We meet Hicks’s special lady, April Randazzo. She’s a femme fatale, folks, a singer-dancer making the late night speakeasy scene. Hicks and April seem like a suave match, but we learn that she has a fetish for married men: “A gold-accented ring finger has the same effect on April as a jigging spoon on a Lake trout, especially when kept on while kidding around, good as a framed copy of a marriage license hanging up on a love-nest wall.”

Note the kidding around there; perhaps Pynchon teases kidness as the illusion of a romanticized time of faux-innocence, an idealized (and ironized) notion of primeval purity. “Any town but this one / Couldn’t we be kids again” croons April in “what’s gotten to be her trademark ballad, backed by a minor-key semi-Cuban arrangement for accordion, saxes, banjo-uke, melancholically muted trumpet.”

Oh and before I forget, our glow-in-the dark fetish for this episode is delivered from Hicks’s “hip flask from which he pours not hooch but some slow green liquid, rubs it between his hands, runs both hands through his hair as an intensely herbal aroma fills the room…” (21). Hicks attests that his hair jelly “Lasts for days, glows in the dark” (21).

(Parenthetically–we get our first two Pynchon songs in this chapter, one from Hicks and one from April (as cited above.) The chapter ends with Hicks getting nudged again, this time to visit his Uncle Lefty, a retired cop.)

Chapter 4 starts at Uncle Lefty and Aunt Peony’s house. They, sorta, raised Hicks; like his protege Skeet (and every other hero), Hicks is an orphan.

Uncle Lefty has prepared a special “Surprise Casserole [in which] Hicks can detect sport peppers, canned pineapple, almost-familiar pork parts marinated in Uncle Lefty’s private cure, based on wildcat beer from a glazed-crock studio just across the Viaduct.” Here, a pineapple is a pineapple. But it can still be part of a surprise.

Uncle Lefty’s name is a bit ironic. He opines: “Der Führer,” gently, “is der future, Hicks. Just the other day the Journal calls him ‘that intelligent young German Fascist.’ ”

Aunt Peony is more sympathetic. We learn that her words have taken on an edge as her marriage advanced, “as if some maidenly spirit, searching and pious, has set out on a trip Peony has no plans herself to make, toward a destiny quietly lifted away from her when she wasn’t looking.” Unlike Daphne (and April?), Peony failed to make her escape in good time.

We learn of Hicks’s fresh-out-of-school job as a strikebreaker. This job would generally make him on the wrong side in Pynchonian terms, but the novel extends some heartstrings his way, pulling him over to the light. Hicks, it seems, would not turn a Pinkerton villain the likes of which Pynchon castigated in Against the Day. His road to Damascus moment happens when his “lead-filled beavertail sap” disappears before he can decimate a striking “truculent little Bolshevik.” The metaphysics of this disappearing object has a profound effect on our hero.

A bit later in the chapter, Boynt offers a through-a-glass-darkly description of Milwaukee, Cream City USA, evoking, “Hitler kiddies, Sicilian mob, secret hallways and exit tunnels, smoke too thick to see through, half a dozen different languages, any lowlife thinks they can turn a nickel always after you for somethin, there’s your wholesome Cream City, kid, mental hygiene paradise but underneath running off of a heartbeat crazy as hell, that’s if it had a heart which it don’t.”

There’s the invisible world, but it might sometimes glow in the dark.

Chapter 4 segues into Chapter 5; Uncle Lefty tells Hicks to talk to ex-vaudeville mentalist Thessalie Wayward. They meet at Velocity Lunch, a cafe where “Today’s Special [is] a vivid green salad centerpiece the size and shape of a human brain, molded in lime Jell-O, versions of which have actually been observed to glow.” Hicks is hoping to learn more about the metaphysical disappearance of his beavertail sap–what divine hand intervened to prevent his killing another person?

Thessalie teaches him about ass and app: “Asported. When something disappears suddenly off to someplace else, in the business that’s called an asport. Coming in at you the other way, appearing out of nowhere, that’s an ‘apport.’ Happens in séances a lot, kind of side effect. Ass and app, as we say.”

After some speculation on this “unnamed force,” Thessalie sends Hicks out again, this time to “Talk to Lew.”

That Lew, as we see in Chapter 6, is none other than Lew Basnight, one of the many heroes of Pynchon’s opus Against the Day (which, so far, Shadow Ticket feels very much akin to). Lew’s chapter is beautiful, short and sweet, a kind of elegy for Western phantasia. He was already late to the Manifest Destiny goldrush: “Didn’t even get out there till late in life, after years of dancin the Pinkertonian around what only a couple of old-timers were still callin the Wild West anymore. Hell, I’m ready to go back…”

Pynchon then extends Lew’s fantasy of returning to a mythical Old West via “lucid dreaming… flown in from strange suburban distances, past radio antennas and skyscrapers, down the gloomy city canyons, skimming echo to echo, banking into the Dearborn station, flown invisible, ticketless, right onto the Santa Fe Chief. And away. Away, so easy…” An escape from the Modern world. Invisible, ticketless–that’s the fantasy.

Lew’s episode ends with a warning to Hicks not to become “another one of these metaphysical detectives, out looking for Revelation.”

In Chapter 7, Hicks takes his (his?) gal April to Chicago to see Dracula. April’s smitten by Bela Lugosi, and “Soon she is sending away to Johnson Smith down in Racine for a set of Glow-in-the-Dark Vampire Choppers, 35¢ postpaid.”

A paragraph later our hero is getting some bad news about his (his..?) gal April and one Don Peppino Infernacci. “April Randazzo is in fact the promised bride of evil,” we learn; Infernacci (good golly that name, Pynchon, chill) is “lord of the underworld.”

Infernacci could be Hades, but April doesn’t strike me as a Persephone. But we’ll see.

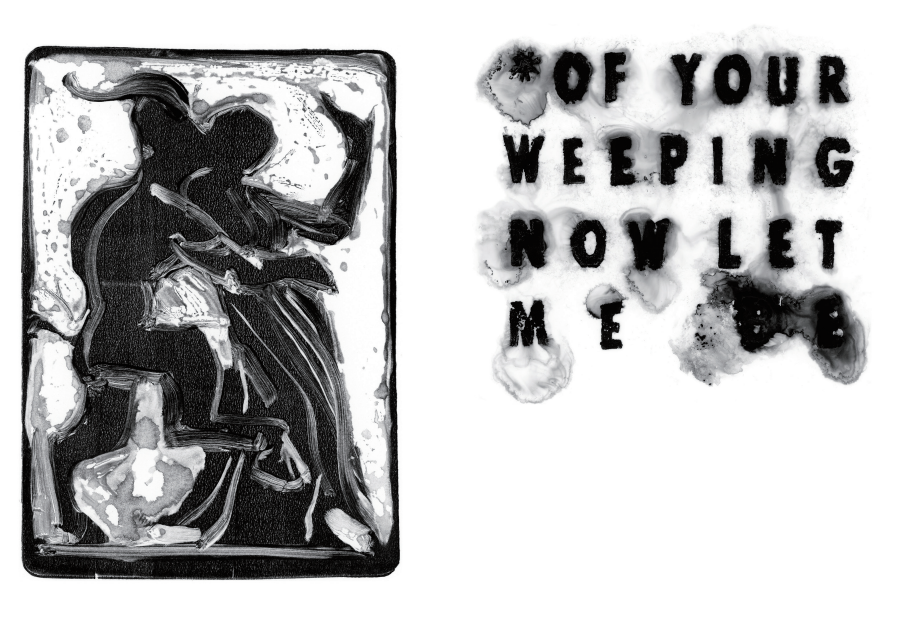

The title track, “Chrysanthemum” is a surreal noir fantasia punctured by a cup of coffee, with daemon lover James Harris hovering menacingly in the background. It seems to reinterpret Shirley Jackson as does the aforementioned “The Tooth” — itself a revision of

The title track, “Chrysanthemum” is a surreal noir fantasia punctured by a cup of coffee, with daemon lover James Harris hovering menacingly in the background. It seems to reinterpret Shirley Jackson as does the aforementioned “The Tooth” — itself a revision of