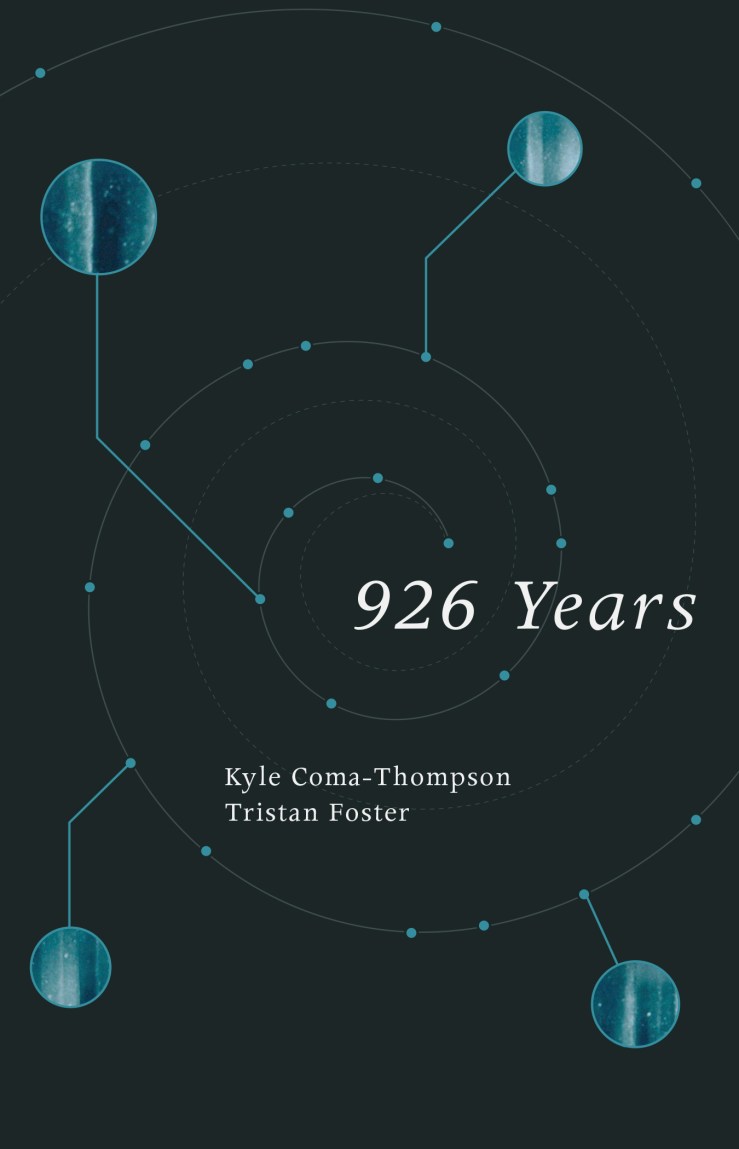

926 Years is a collaboration between Kyle Coma-Thompson and Tristan Foster. The book consists of 22 stories, each a paragraph long, and each paragraph no longer than the front and back of a 4.5″ x 7″ page. Each story is titled after a character plus the character’s age (e.g. “Chaplain Blake, age 60”; “Sebastian, age 30”; “Marty Fantastic, age 81”). (I have not done the math to see if all the ages add up to 926.) Although the characters never meet in the book’s prose, key sentences suggest that they may be connected via the reader’s imagination.

Indeed, the blurb on the back of 926 Years describes the book as “twenty-two linked stories.” After reading it twice, I don’t see 926 Years so much as a collection of connected tales, but rather as a kind of successful experimental novel, a novel that subtly and reflexively signals back to its own collaborative origin. Coma-Thompson lives in Louisville, Kentucky and Foster lives in Sydney, New South Wales. They’ve never met in person. And yet they share a common language, of course, and other common cultural forces surely shape their prose. (Melville’s Ishmael refers to Australia as “That great America on the other side of the sphere” in Ch. 24 of Moby-Dick.)

The book’s prose offers a consistency to the apparently discontinuous narrative pieces that comprise 926 Years. My first assumption was that Coma-Thompson and Foster traded narratives, but as I read and re-read, the prose’s stylistic consistency struck me more as a work of synthesis, of two writers tuning to each other and humming a new frequency. The sentences of 926 Years are predominantly short, and often fall into fragmentation, or elide their grammatical subject. Here’s an example from “Shelley Valentine, age 34”:

A flare of sansho pepper on the tongue tip. Catch the tree at the right time of year and the fruit bursts, raining peppercorns down. Maybe like the season when pistachios open, the night snapping like broken locust song. Used for seasoning eel. Sansho leaves for garnishing fish. Clap it between the hands for aroma, make a wish, the finishing touch to the perfect soup. In Korea, the unripe fruit was used for fishing. Poisonous to the smallest ones. That was cheating wasn’t it? Or was pulling up the fish all that mattered?

Eventually we can attribute these fragmented thoughts to Shelley Valentine, now well out of her magic twenties, drinking sansho-peppered gin and tonics in a “New bar, same lost , of course.” She’ll leave alone.

The characters in 926 Years move between isolation and connection, between fragmentation and re-integration. Here’s Larry Hoavis (age 47, by the way), sitting in a lawn chair in his rural backyard:

Why does it feel lonely, sitting and watching? Nature in its subtle power and monotony, pre-Internet to the core, unconscious of its enormity. No one. No one knows he’s even here. The house at his back. Divorced. His ex elsewhere, how he loved her, hurt her, himself. Why’s it beautiful, why’s it comforting, that no one knows?

Hoavis’s lonely transcendental private (and tequila-tinged) reverie of disconnection reinforces 926 Years’ themes of interconnection coupled with disintegration. In one of my favorite tales, “Lew Wade Wiley, age 55,” we learn of the “Spoiled heir of the Prudential fortune” who collects other people’s lives. He has them brought to his Boston penthouse to offer

…their worst fears, desires, the messy embarrassments of their commonalities…these he worked into undead monotone prose, the diary of Lew Wade Wiley, and so lived fuller than anyone who’d opened a newspaper to read those advertisements, wrote to that listed address, knocked at his penthouse door.

The adjective “undead” above fits into a resurrection motif that floats through 926 Years, whether it be the lifeforce of currency or the proverbial powers of cats to cheat death. Sometimes the resurrection is a kind of inspiriting force, as one character, overwhelmed by aesthetic possibility that “knocked the air out of him” experiences: “It had reminded him of a moment in a childhood that wasn’t his.”

Elsewhere, we see resurrection at a genetic level, as in “Mrs. Anderson, age 67,” whose psychologist describes to her the “cherry blossom” experiment, the results of which suggest that fear and anxiety to specific aesthetic stimuli can be passed down from generation to generation.

Reincarnation becomes both figurative and literal in the case of the lounge star Marty Fantastic, “Eighty-one-year-old darling with ten faces (one for each lift)…The plague of identities—who to be tonight, Peggy Lee, Rod Stewart, Cole Porter, Journey?” The oldest (and penultimate) character in 926 Years, Marty reflects on his own death as he gazes at his audience: “The songs of their future–what about those? They lyrics set in stone, the melodies: unknown.” The lovely little couplet suggest a complex relationship of aesthetic substance and aesthetic spirit.

The final piece in 926 Years–well, I won’t spoil it, I’ll simply say it kept me thinking, made me happy in a strange, nervous way. It features the youngest character in the book, and it points clearly if subtly to the book’s affirmation of imaginative and aesthetic possibility as a kind of crucial lifeforce. I’ll close instead with something from the book’s third tale, a little moment early on when 926 Years clicked for me:

Much as the geese and other such birds at the beginning of winter months fly south towards more temperate climates, it’s the nature of human beings to move in unconscious arrow formation as well. They take turns, leading the pack. The burden of cutting resistance through the air, something they share. Others fly, you see, in the wake; and that is why they form a V. The wake makes for easy flying, particularly at the furthest, outermost edges. The ones in the rear work less, conserve strength, eventually make their way towards the top of the V, tip of the arrow, then when it’s time and the leader has tired, assume the vanguard position. It is written into them by instinct to share the effort, burrowing southwards through the sky; that nevertheless sky we all live below.

926 Years is available now from Sublunary Editions.