Last week I crammed my thoughts about the death of Prince into one of these “Three Books” posts I’ve doing each Sunday for around 30 Sundays now (I plan to do 52, if anyone cares or counts). I grabbed a bunch of purple books and scanned them, and I still have the scans saved, so today’s Three Books are, I guess, books that I deemed not-quite-purple-enough for last week’s post. My thoughts on Prince remain the same: I’m still vaguely shocked at his death and shocked at my shock at his death. I tried to write a Thing on Prince’s sexy dystopian visions, but I failed. Give me the electric chair 4 all my future crimes.

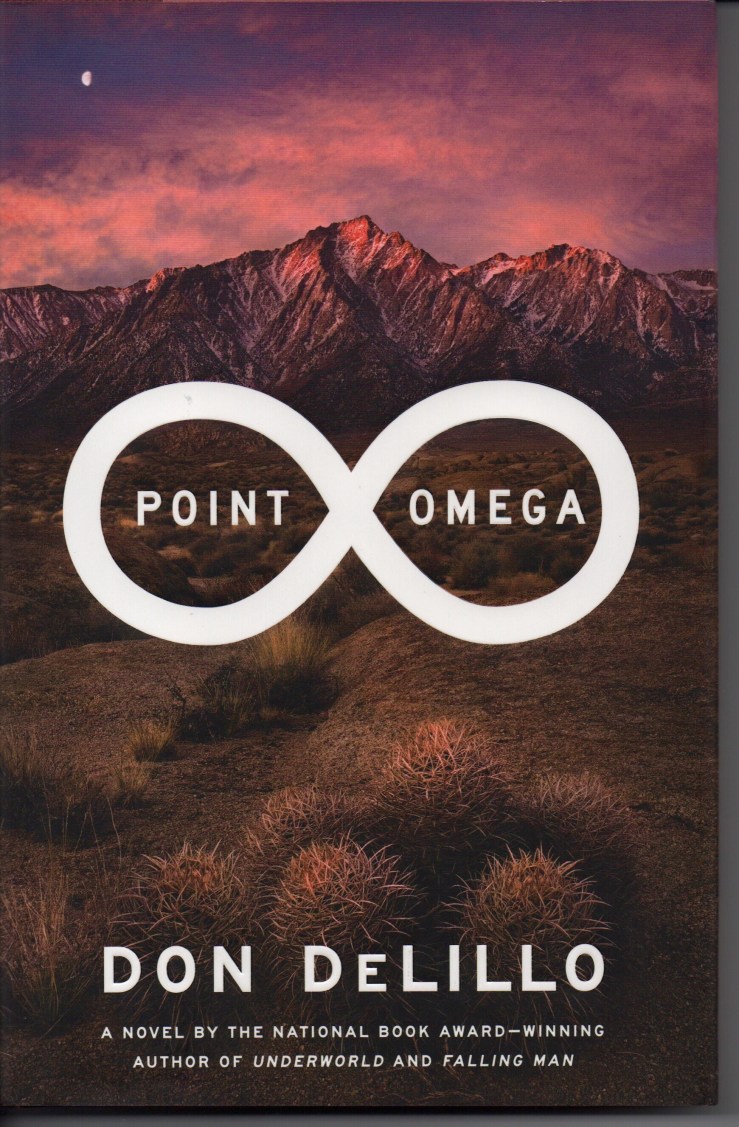

Point Omega by Don DeLillo. First edition hardback, Scribner, 2010. Jacket design by Rex Bonomelli using a photograph by Marc Adamus. I reviewed Point Omega when it came out, noting that it “is not a particularly fun book nor does it yield any direct answers, but it’s also a rewarding, engaging, and often challenging read.” The book got somewhat mixed reviews, but I think in retrospect it’s quite underrated. DeLillo wrote one of the earliest paraphrases of the Bush Wars here (without really writing a summation and without really writing a war novel), and I think about the book often—whenever I read a little digital clipping about Cheney or Wolfowitz or Rumsfeld or any of the Old Neocon Gang—and the hacks and mouthpieces who supported them.

Masscult and Midcult: Essays against the American Grain by Dwight Macdonald. Edited by John Summers. Published by NYRB, 2011. Cover design by Katy Homans; the cover image is a detail of Cedric Delsaux’s photograph 88, Las Vegas Casino 1. I reviewed Masscult a few years ago. The book has some perceptive essays, and its title essay is essential cultural criticism.

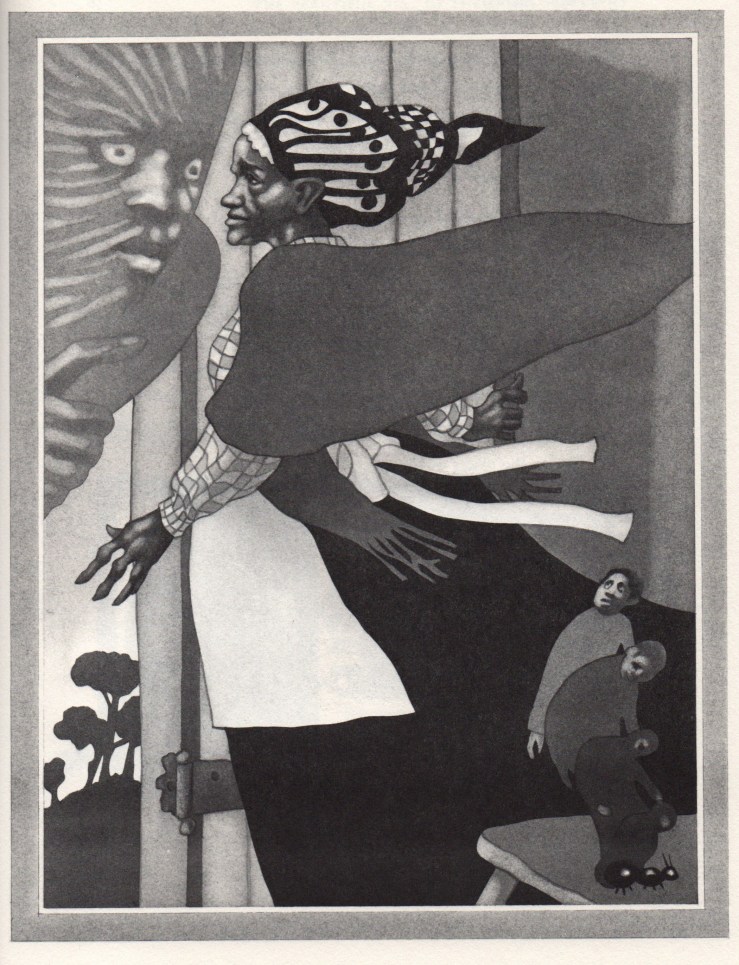

Native Son by Richard Wright. Mass market paperback edition by Harper Perennial, 1993. Cover design and illustration by David Diaz. This book was part of a class set I used years ago when I taught AP English Literature. It left with me when I left that job.