Dream delivers us to dream, and there is no end to illusion. Life is a train of moods like a string of beads, and as we pass through them they prove to be many-colored lenses which paint the world their own hue, and each shows only what lies in its focus. From the mountain you see the mountain. We animate what we can, and we see only what we animate. Nature and books belong to the eyes that see them. It depends on the mood of the man whether he shall see the sunset or the fine poem. There are always sunsets, and there is always genius; but only a few hours so serene that we can relish nature or criticism. The more or less depends on structure or temperament. Temperament is the iron wire on which the beads are strung. Of what use is fortune or talent to a cold and defective nature? Who cares what sensibility or discrimination a man has at some time shown, if he falls asleep in his chair? or if he laugh and giggle? or if he apologize? or is infected with egotism? or thinks of his dollar? or cannot go by food? or has gotten a child in his boyhood? Of what use is genius, if the organ is too convex or too concave and cannot find a focal distance within the actual horizon of human life? Of what use, if the brain is too cold or too hot, and the man does not care enough for results to stimulate him to experiment, and hold him up in it? or if the web is too finely woven, too irritable by pleasure and pain, so that life stagnates from too much reception without due outlet? Of what use to make heroic vows of amendment, if the same old law-breaker is to keep them? What cheer can the religious sentiment yield, when that is suspected to be secretly dependent on the seasons of the year and the state of the blood? I knew a witty physician who found the creed in the biliary duct, and used to affirm that if there was disease in the liver, the man became a Calvinist, and if that organ was sound, he became a Unitarian. Very mortifying is the reluctant experience that some unfriendly excess or imbecility neutralizes the promise of genius. We see young men who owe us a new world, so readily and lavishly they promise, but they never acquit the debt; they die young and dodge the account; or if they live they lose themselves in the crowd.

Category: Literature

The primary meaning of the gothic romance, then, lies in its substitution of terror for love as a central theme of fiction

The primary meaning of the gothic romance, then, lies in its substitution of terror for love as a central theme of fiction. The titillation of sex denied, it offers its readers a vicarious participation in a flirtation with death—approach and retreat, approach and retreat, the fatal orgasm eternally mounting and eternally checked. More than that, however, the gothic is the product of an implicit aesthetic that replaces the classic concept of nothing-in-excess with the revolutionary doctrine that nothing succeeds like excess. Aristotle’s guides for achieving the tragic without falling into “the abominable” are stood on their heads, “the abominable” itself being made the touchstone of effective art. Dedicated to producing nausea, to transcending the limits of taste and endurance, the gothic novelist is driven to seek more and more atrocious crimes to satisfy the hunger for “too-much” on which he trades.

It is not enough that his protagonist commit rape; he must commit it upon his mother or sister; and if he himself is a cleric, pledged to celibacy, his victim a nun, dedicated to God, all the better! Similarly, if he commits murder, it must be his father who is his victim; and the crime must take place in darkness, among the decaying bodies of his ancestors, on hallowed ground. It is as if such romancers were pursuing some ideal of absolute atrocity which they cannot quite flog their reluctant imaginations into conceiving…

Some would say, indeed, that the whole tradition of the gothic is a pathological symptom rather than a proper literary movement, a reversion to the childish game of scaring oneself in the dark, or a plunge into sadist fantasy, masturbatory horror. For Wordsworth, for instance, heir of the genteel sentimentality of the eighteenth century, gothic sensationalism seemed merely a response (compounding the ill to which it responded) to the decay of sensibility in an industrialized and brutalized world—in which men had grown so callous that only shock treatments of increasing intensity could move them to react.

From Leslie Fiedler’s Love and Death in the American Novel.

This is the reason why bards love wine, mead, narcotics, coffee, tea, opium, the fumes of sandal-wood and tobacco (Emerson)

It is a secret which every intellectual man quickly learns, that, beyond the energy of his possessed and conscious intellect he is capable of a new energy (as of an intellect doubled on itself), by abandonment to the nature of things; that beside his privacy of power as an individual man, there is a great public power on which he can draw, by unlocking, at all risks, his human doors, and suffering the ethereal tides to roll and circulate through him; then he is caught up into the life of the Universe, his speech is thunder, his thought is law, and his words are universally intelligible as the plants and animals. The poet knows that he speaks adequately then only when he speaks somewhat wildly, or, “with the flower of the mind;” not with the intellect used as an organ, but with the intellect released from all service and suffered to take its direction from its celestial life; or as the ancients were wont to express themselves, not with intellect alone but with the intellect inebriated by nectar. As the traveller who has lost his way throws his reins on his horse’s neck and trusts to the instinct of the animal to find his road, so must we do with the divine animal who carries us through this world. For if in any manner we can stimulate this instinct, new passages are opened for us into nature; the mind flows into and through things hardest and highest, and the metamorphosis is possible.

This is the reason why bards love wine, mead, narcotics, coffee, tea, opium, the fumes of sandal-wood and tobacco, or whatever other procurers of animal exhilaration. All men avail themselves of such means as they can, to add this extraordinary power to their normal powers; and to this end they prize conversation, music, pictures, sculpture, dancing, theatres, travelling, war, mobs, fires, gaming, politics, or love, or science, or animal intoxication,—which are several coarser or finer quasi-mechanical substitutes for the true nectar, which is the ravishment of the intellect by coming nearer to the fact. These are auxiliaries to the centrifugal tendency of a man, to his passage out into free space, and they help him to escape the custody of that body in which he is pent up, and of that jail-yard of individual relations in which he is enclosed. Hence a great number of such as were professionally expressers of Beauty, as painters, poets, musicians, and actors, have been more than others wont to lead a life of pleasure and indulgence; all but the few who received the true nectar; and, as it was a spurious mode of attaining freedom, as it was an emancipation not into the heavens but into the freedom of baser places, they were punished for that advantage they won, by a dissipation and deterioration. But never can any advantage be taken of nature by a trick. The spirit of the world, the great calm presence of the Creator, comes not forth to the sorceries of opium or of wine. The sublime vision comes to the pure and simple soul in a clean and chaste body. That is not an inspiration, which we owe to narcotics, but some counterfeit excitement and fury. Milton says that the lyric poet may drink wine and live generously, but the epic poet, he who shall sing of the gods and their descent unto men, must drink water out of a wooden bowl. For poetry is not ‘Devil’s wine,’ but God’s wine. It is with this as it is with toys. We fill the hands and nurseries of our children with all manner of dolls, drums, and horses; withdrawing their eyes from the plain face and sufficing objects of nature, the sun, and moon, the animals, the water, and stones, which should be their toys. So the poet’s habit of living should be set on a key so low that the common influences should delight him. His cheerfulness should be the gift of the sunlight; the air should suffice for his inspiration, and he should be tipsy with water. That spirit which suffices quiet hearts, which seems to come forth to such from every dry knoll of sere grass, from every pine-stump and half-imbedded stone on which the dull March sun shines, comes forth to the poor and hungry, and such as are of simple taste. If thou fill thy brain with Boston and New York, with fashion and covetousness, and wilt stimulate thy jaded senses with wine and French coffee, thou shalt find no radiance of wisdom in the lonely waste of the pinewoods.

God has not made some beautiful things, but Beauty is the creator of the universe (Emerson)

The poet is the sayer, the namer, and represents beauty. He is a sovereign, and stands on the centre. For the world is not painted or adorned, but is from the beginning beautiful; and God has not made some beautiful things, but Beauty is the creator of the universe. Therefore the poet is not any permissive potentate, but is emperor in his own right. Criticism is infested with a cant of materialism, which assumes that manual skill and activity is the first merit of all men, and disparages such as say and do not, overlooking the fact that some men, namely poets, are natural sayers, sent into the world to the end of expression, and confounds them with those whose province is action but who quit it to imitate the sayers. But Homer’s words are as costly and admirable to Homer as Agamemnon’s victories are to Agamemnon. The poet does not wait for the hero or the sage, but, as they act and think primarily, so he writes primarily what will and must be spoken, reckoning the others, though primaries also, yet, in respect to him, secondaries and servants; as sitters or models in the studio of a painter, or as assistants who bring building materials to an architect.

For poetry was all written before time was, and whenever we are so finely organized that we can penetrate into that region where the air is music, we hear those primal warblings and attempt to write them down, but we lose ever and anon a word or a verse and substitute something of our own, and thus miswrite the poem. The men of more delicate ear write down these cadences more faithfully, and these transcripts, though imperfect, become the songs of the nations. For nature is as truly beautiful as it is good, or as it is reasonable, and must as much appear as it must be done, or be known. Words and deeds are quite indifferent modes of the divine energy. Words are also actions, and actions are a kind of words.

The sign and credentials of the poet are that he announces that which no man foretold. He is the true and only doctor; he knows and tells; he is the only teller of news, for he was present and privy to the appearance which he describes. He is a beholder of ideas and an utterer of the necessary and causal. For we do not speak now of men of poetical talents, or of industry and skill in metre, but of the true poet.

He says that he will never die (Blood Meridian)

And they are dancing, the board floor slamming under the jackboots and the fiddlers grinning hideously over their canted pieces. Towering over them all is the judge and he is naked dancing, his small feet lively and quick and now in doubletime and bowing to the ladies, huge and pale and hairless, like an enormous infant. He never sleeps, he says. He says he’ll never die. He bows to the fiddlers and sashays backwards and throws back his head and laughs deep in his throat and he is a great favorite, the judge. He wafts his hat and the lunar dome of his skull passes palely under the lamps and he swings about and takes possession of one of the fiddles and he pirouettes and makes a pass, two passes, dancing and fiddling at once. His feet are light and nimble. He never sleeps. He says that he will never die. He dances in light and in shadow and he is a great favorite. He never sleeps, the judge. He is dancing, dancing. He says that he will never die.

The last paragraph (excepting the epilogue) of Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian.

Seven quick thoughts:

- I’ve read Blood Meridian more times than probably any book but I still don’t know what it means.

- Hats, bears, coins, shadows, dancing.

- The judge is a metaphysical entity, but what?

- I think McCarthy’s is pointing to something past the devil.

- The kid definitely dies at the end.

- But how definitely—no body, no corpse?

- I’ll read it again, of course.

The terrible handicap of being young (Faulkner)

His father had struck him before last night but never before had he paused afterward to explain why; it was as if the blow and the following calm, outrageous voice still rang, repercussed, divulging nothing to him save the terrible handicap of being young, the light weight of his few years, just heavy enough to prevent his soaring free of the world as it seemed to be ordered but not heavy enough to keep him footed solid in it, to resist it and try to change the course of its events.

From William Faulkner’s story “Barn Burning.”

Nathaniel Hawthorne’s journal entry for September 26th, 1841

Brook Farm, September 26th.–A walk this morning along the Needham road. A clear, breezy morning, after nearly a week of cloudy and showery weather. The grass is much more fresh and vivid than it was last month, and trees still retain much of their verdure, though here and there is a shrub or a bough arrayed in scarlet and gold. Along the road, in the midst of a beaten track, I saw mushrooms or toad-stools which had sprung up probably during the night.

The houses in this vicinity are, many of them, quite antique, with long, sloping roofs, commencing at a few feet from the ground, and ending in a lofty peak. Some of them have huge old elms overshadowing the yard. One may see the family sleigh near the door, it having stood there all through the summer sunshine, and perhaps with weeds sprouting through the crevices of its bottom, the growth of the months since snow departed. Old barns, patched and supportedby timbers leaning against the sides, and stained with the excrement of past ages.

In the forenoon I walked along the edge of the meadow towards Cow Island. Large trees, almost a wood, principally of pine with the green pasture-glades intermixed, and cattle feeding. They cease grazing when an intruder appears, and look at him with long and wary observation, then bend their heads to the pasture again. Where the firm ground of the pasture ceases, the meadow begins,–loose, spongy, yielding to the tread, sometimes permitting the foot to sink into black mud, or perhaps over ankles in water. Cattle-paths, somewhat firmer than the general surface, traverse the dense shrubbery which has overgrown the meadow. This shrubbery consists of small birch, elders, maples, and other trees, with here and there white-pines of larger growth. The whole is tangled and wild and thick-set, so that it is necessary to part the nestling stems and branches, and go crashing through. There are creeping plants of various sorts which clamber up the trees; and some of them have changed color in the slight frosts which already have befallen these low grounds, so that one sees a spiral wreath of scarlet leaves twining up to the top of a green tree, intermingling its bright hues with their verdure, as if all were of one piece. Sometimes, instead of scarlet, the spiral wreath is of a golden yellow.

Within the verge of the meadow, mostly near the firm shore of pasture ground, I found several grapevines, hung with an abundance of large purple grapes. The vines had caught hold of maples and alders, and climbed to the summit, curling round about and interwreathing their twisted folds in so intimate amanner that it was not easy to tell the parasite from the supporting tree or shrub. Sometimes the same vine had enveloped several shrubs, and caused a strange, tangled confusion, converting all these poor plants to the purpose of its own support, and hindering their growing to their own benefit and convenience. The broad vine-leaves, some of them yellow or yellowish-tinged, were seen apparently growing on the same stems with the silver-mapled leaves, and those of the other shrubs, thus married against their will by the conjugal twine; and the purple clusters of grapes hung down from above and in the midst, so that one might “gather grapes,” if not “of thorns,” yet of as alien bushes.

One vine had ascended almost to the tip of a large white-pine, spreading its leaves and hanging its purple clusters among all its boughs,–still climbing and clambering, as if it would not be content till it had crowned the very summit with a wreath of its own foliage and bunches of grapes. I mounted high into the tree, and ate the fruit there, while the vine wreathed still higher into the depths above my head. The grapes were sour, being not yet fully ripe. Some of them, however, were sweet and pleasant.

Nathaniel Hawthorne’s journal entry for September 26th, 1841. From Passages from the American Note-Books.

Inversions without end (Blood Meridian)

As they rode that night upon the mesa they saw come toward them much like their own image a party of riders pieced out of the darkness by the intermittent flare of the dry lightning to the north. Glanton halted and sat his horse and the company halted behind him. The silent riders hove on. When they were a hundred yards out they too halted and all sat in silent speculation at this encounter.

Who are you? called Glanton.

Amigos, somos amigos.

They were counting each the other’s number.

De donde viene? called the strangers.

A donde va? called the judge.

They were ciboleros down from the north, their packhorses laden with dried meat. They were dressed in skins sewn with the ligaments of beasts and they sat their animals in the way of men seldom off them. They carried lances with which they hunted the wild buffalo on the plains and these weapons were dressed with tassels of feathers and colored cloth and some carried bows and some carried old fusils with tasseled stoppers in their bores. The dried meat was packed in hides and other than the few arms among them they were innocent of civilized device as the rawest savage of that land.

They parleyed without dismounting and the ciboleros lighted their small cigarillos and told that they were bound for the markets at Mesilla. The Americans might have traded for some of the meat but they carried no tantamount goods and the disposition to exchange was foreign to them. And so these parties divided upon that midnight plain, each passing back the way the other had come, pursuing as all travelers must inversions without end upon other men’s journeys.

The last few paragraphs of Ch. IX of Cormac McCarthy’s novel Blood Meridian. The inversion here points towards the novel’s palindromic structure (I would link that phrase “palindromic structure” to Christopher Forbis’s essay “Of Judge Holden’s Hats; Or, the Palindrome in Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian“—only I can’t seem to find it online anymore).

“My husband met some women online and I found out” | Read Joanna Walsh’s story “Online”

Electric Literature has published “Online,” a story from Joanna Walsh’s forthcoming collection Vertigo. You can buy Vertigo now from the indie imprint Dorothy (I ordered Vertigo along with Marianne Fritz’s The Weight of Things), the publisher who brought us Nell Zink’s The Wallcreeper.

The first few paragraphs of Walsh’s “Online”:

My husband met some women online and I found out.

His women were young, witty, and charming, and they had good jobs—at least I ignored the women he had met online who were not young, witty, and charming, and who did not have good jobs—and so I fell more in love with my husband, reflected as he was, in the words of these universally young, witty, and charming women.

I had neglected my husband.

Now I wanted him back.

So I tried to be as witty and charming as the women my husband had met online.

I tried to take an interest.

At breakfast, I said to him, “How is your breakfast?”

He said to me, “Fine, thanks.”

I said to him, “What do you like for breakfast?”

(Having lived with him for a number of years, I already know what my husband likes for breakfast, and this is where the women online have the advantage of me: they do not yet know what my husband likes for breakfast and so they can ask him what he likes for breakfast and, in that way, begin a conversation.)

He did not answer my question.

“The History of the Apple Tree” — Henry David Thoreau

“The History of the Apple Tree”

by

Henry David Thoreau

from “Wild Apples.”

It is remarkable how closely the history of the Apple-tree is connected with that of man. The geologist tells us that the order of the Rosaceae, which includes the Apple, also the true Grasses, and the Labiatae or Mints, were introduced only a short time previous to the appearance of man on the globe.

It appears that apples made a part of the food of that unknown primitive people whose traces have lately been found at the bottom of the Swiss lakes, supposed to be older than the foundation of Rome, so old that they had no metallic implements. An entire black and shrivelled Crab-Apple has been recovered from their stores.

Tacitus says of the ancient Germans, that they satisfied their hunger with wild apples (agrestia poma) among other things.

Niebuhr observes that “the words for a house, a field, a plough, ploughing, wine, oil, milk, sheep, apples, and others relating to agriculture and the gentler way of life, agree in Latin and Greek, while the Latin words for all objects pertaining to war or the chase are utterly alien from the Greek.” Thus the apple-tree may be considered a symbol of peace no less than the olive.

The apple was early so important, and generally distributed, that its name traced to its root in many languages signifies fruit in general. [Greek: Maelon], in Greek, means an apple, also the fruit of other trees, also a sheep and any cattle, and finally riches in general.

The apple-tree has been celebrated by the Hebrews, Greeks, Romans, and Scandinavians. Some have thought that the first human pair were tempted by its fruit. Goddesses are fabled to have contended for it, dragons were set to watch it, and heroes were employed to pluck it.

The tree is mentioned in at least three places in the Old Testament, and its fruit in two or three more. Solomon sings,—”As the apple-tree among the trees of the wood, so is my beloved among the sons.” And again,—”Stay me with flagons, comfort me with apples.” The noblest part of man’s noblest feature is named from this fruit, “the apple of the eye.”

The apple-tree is also mentioned by Homer and Herodotus. Ulysses saw in the glorious garden of Alcinous “pears and pomegranates, and apple-trees bearing beautiful fruit” (kai maeleui aglaokarpoi). And according to Homer, apples were among the fruits which Tantalus could not pluck, the wind ever blowing their boughs away from him. Theophrastus knew and described the apple-tree as a botanist.

According to the Prose Edda, “Iduna keeps in a box the apples which the gods, when they feel old age approaching, have only to taste of to become young again. It is in this manner that they will be kept in renovated youth until Ragnarök” (or the destruction of the gods).

I learn from Loudon that “the ancient Welsh bards were rewarded for excelling in song by the token of the apple-spray;” and “in the Highlands of Scotland the apple-tree is the badge of the-clan Lamont.” Continue reading ““The History of the Apple Tree” — Henry David Thoreau”

Fabled horde, legion of horribles | Blood Meridian riff

The captain watched through the glass.

I suppose they’ve seen us, he said.

They’ve seen us.

How many riders do you make it?

A dozen maybe.

The captain tapped the instrument in his gloved hand.

They dont seem concerned, do they?

No sir. They dont.

The captain smiled grimly. We may see a little sport here before the day is out.

The first of the herd began to swing past them in a pall of yellow dust, rangy slatribbed cattle with horns that grew agoggle and no two alike and small thin mules coalblack that shouldered one another and reared their malletshaped heads above the backs of the others and then more cattle and finally the first of the herders riding up the outer side and keeping the stock between themselves and the mounted company. Behind them came a herd of several hundred ponies. The sergeant looked for Candelario. He kept backing along the ranks but he could not find him. He nudged his horse through the column and moved up the far side. The lattermost of the drovers were now coming through the dust and the captain was gesturing and shouting. The ponies had begun to veer off from the herd and the drovers were beating their way toward this armed hides the painted chevrons and the hands and rising suns and birds and fish of every device like the shade of old work through sizing on a canvas and now too you could hear above the pounding of the unshod hooves the piping of the quena, flutes made from human bones, and some among the company had begun to saw back on their mounts and some to mill in confusion when up from the offside of those ponies there rose a fabled horde of mounted lancers and archers bearing shields bedight with bits of broken mirrorglass that cast a thousand unpieced suns against the eyes of their enemies. A legion of horribles, hundreds in number, half naked or clad in costumes attic or biblical or wardrobed out of a fevered dream with the skins of animals and silk finery and pieces of uniform still tracked with the blood of prior owners, coats of slain dragoons, frogged and braided cavalry jackets, one in a stovepipe hat and one with an umbrella and one in white stockings and a bloodstained weddingveil and some in headgear of cranefeathers or rawhide helmets that bore the horns of bull or buffalo and one in a pigeontailed coat worn backwards and otherwise naked and one in the armor of a Spanish conquistador, the breastplate and pauldrons deeply dented with old blows of mace or sabre done in another country by men whose very bones were dust and many with their braids spliced up with the hair of other beasts until they trailed upon the ground and their horses’ ears and tails worked with bits of brightly colored cloth and one whose horse’s whole head was painted crimson red and all the horsemen’s faces gaudy and grotesque with daubings like a company of mounted clowns, death hilarious, all howling in a barbarous tongue and riding down upon them like a horde from a hell more horrible yet than the brim tone land of Christian reckoning, screeching and yammering and clothed in smoke like those vaporous beings in regions beyond right knowing where the eye wanders and the lip jerks and drools.

Oh my god, said the sergeant.

- The legion of horribles passage comes near the end of Ch. IV of Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, and is probably the passage I see cited most often from the book—which makes sense: It comes early enough in the novel and doesn’t really need much context—other than its own language—to mean. And of course its language—well, that’s the occasion, yes? The passage condenses the book’s violence into a baroque and surreal fevered dream (to steal a phrase from the passage). We have here an ornate parcel, a prefiguration of ecstatic violence.

- I remember the first time I read this passage. It was 2008, very late at night, and it just sort of short circuited whatever brains I had left. I had to go back and start the novel again, hit reset. I’m revisiting Blood Meridian (I’ve reread it at least once every year since I first read it, a common practice of many of its fans I’ve realized over the years) after having just revisited Suttree. Blood Meridian always seems funnier and darker, and somehow—how?!—more violent.

- The legion of horribles passage is not acutely violent in and of itself; rather it stages the violence that explodes in the next few paragraphs, a dizzying, overwhelming violence. Scenes of rape and murder.

- I claimed in my first paragraph that the passage doesn’t require context, but here’s some anyway: We have there at the beginning Captain White and his sergeant. White—appropriately named—plans to lead his unauthorized band of irregulars into Mexico to loot and spoil and steal. He’s recruited the kid, the would-be protagonist of Blood Meridian. With its vile nativism, xenophobia, and racism, Captain White’s recruitment monologue (which doesn’t really persuade the kid as much as the simple promise of a horse, rifle, and saddle) wouldn’t be out of place in American politics today. White’s racism makes his initial impression of the fabled horde that will kill all but a handful of his men—and, spoiler, behead him—all the more ironic/moronic: “We may see a little sport here before the day is out,” he grimly jests. This seems to me almost the set-up to a punchline, with a long excursion into a description of the advancing “horde from hell” as the meat of the joke (Joke!?), with the final punchline/payoff in the sergeant’s dry horrified realization: “Oh my god.”

- In Suttree, McCarthy synthesizes American literature; in Blood Meridian, he’s condensing something more primal. Myth and history, time and space, whorled into blood and violence.

- We can see this condensation of myth and history in the very language of the legion of horribles passage. McCarthy offers a nightmare vision of time collapsed into a single violent, overwhelming space—and as I go now to pull an example, I find that there are too many, that the passage is all example, all detail, all image.

- Or, okay, hell, just one image then—the “armor of a Spanish conquistador, the breastplate and pauldrons deeply dented with old blows of mace or sabre done in another country by men whose very bones were dust”—there, that’s it, that’s all of it, history, myth, violence.

- Or just the words themselves, the diverse diction, culled from so many roots and tongues (attic, biblical)—and the compounding of words (bloodstained, weddingveil, headgear, cranefeathers, rawhide, pigeontailed, etc.), the compression and synthesis of words, the force of the words. The onomatopoeia. The barbaric yawps.

- What happens next? Okay, I’d say, Read the book—but I’ve already told you—the horde eviscerates White’s men. The kid survives, somehow, and the first section of Blood Meridian seems to end—as if this fabled horde, this legion of horribles were merely a preamble to the darker violence to come—a preview of the Glanton Gang and their sinister commandant Judge Holden.

Does Suttree die? | A riff on Cormac McCarthy’s novel Suttree

Does Suttree die?

At the end of Cormac McCarthy’s novel Suttree, I mean?

Look, before we go any farther, let’s be clear—this little riff is intended for those who’ve read the book. Anyone’s welcome to read this riff of course, but I’m not going to be, y’know, summarizing the plot or providing an argument that you should read Suttree (you should; it’s great)—and there will be what I suppose you’d call spoilers.

So anyway—Does Suttree die at the end of Cormac McCarthy’s novel Suttree?

This question percolated in the background of my brain as I revisited Suttree this month via Michael Kramer’s amazing audiobook version (I also reread key sections—especially the last), in large part because of comments made on my 2010 review of the novel.

The first comment suggesting that Suttree dies at the end of the novel came in 2012 from poster “Jack foy,” who suggested that Suttree “has died in the boat and that it is his corpse cariied [sic] from there and his spirit and not his body hitching a ride at the finale.”

Earlier this year, a commenter named Julie Seeley responded to Jack foy’s idea; her response is worth posting in full:

I kind of agree that Suttree dies at the end also–or at least there are a lot of indications that the ending is meant to be ambiguous. Suttree reflects on his life, saying something to the effect of “I was not unhappy.” He visits his own houseboat and finds the door off and a corpse in his bed. A driver picks him up and says, “Come on,” even though Suttree had never even stuck out his thumb to hitch-hike It feels oddly similar to Dickinson’s “Because I could not stop for Death, He kindly stopped for me.” All of the scenery whizzing by faster and faster does feel like (sorry for the cliche) his life sort of flashing before him. This was a thought-provoking novel that I am looking forward to reading again soon.

Julie Seeley’s analysis is persuasive and her connection to Dickinson is especially convincing upon rereading the book’s final paragraphs. In my Suttree review, I argued that the book is a synthesis of American literature, tracing the overt connections to Faulkner and Frost, Poe and Cummings, Ellison and Steinbeck, before laundry listing:

…we find Mark Twain, Herman Melville, Ernest Hemingway, Walt Whitman, Emerson and Thoreau, Emily Dickinson, and William Carlos Williams, to name just a few writers whose blood courses through this novel (even elegant F. Scott Fitzgerald is here, in an unexpected Gatsbyish episode late in the novel).

Revisiting Suttree this month I found myself again impressed with McCarthy’s command of allusion and reference. Its transcendentalist streak stood out in particular. (Or perhaps more accurately, I sensed the generative material of the American Renaissance writers filtered through the writers that came before Suttree). But one American Renaissance writer I failed to name in my original review was Dickinson’s (near) contemporary Nathaniel Hawthorne, whose work of course filters through all serious American novels. There are plenty of echoes of Hawthorne in Suttree—Hawthorne’s tales in particular—but it’s the way that Hawthorne ends his tales that interests me here. Like the dashes that conclude many of Dickinson’s poems (including “Because I could not stop for Death”), Hawthorne’s conclusions are frequently ambiguous. Like the conclusion of Suttree.

So: Does Suttree die at the end of Cormac McCarthy’s novel Suttree?

Well, wait. Let’s go back to the beginning. Of the novel, I mean. Like I said, I’d had this question buzzing around in the back of my head as I revisited the book.

So, the beginning. Well, I’d forgotten that Suttree had a twin brother who had died at birth. The twin resurfaces a few times in the text, and there’s even a scene in the musseling section featuring a set of twins. Does Suttree’s twin brother’s death in infancy prefigure Suttree’s own death? How could it not? But—at the same time—hey, it’s ambiguous if Suttree dies; should I have stated my answer to my own damn question earlier?—hey, at the same time, the twin brother’s death is not Suttree’s death sentence, right? It simply introduces a motif—the dead body. Continue reading “Does Suttree die? | A riff on Cormac McCarthy’s novel Suttree”

Nathaniel Hawthorne’s journal entry of September 18th, 1842

September 18th.–How the summer-time flits away, even while it seems to be loitering onward, arm in arm with autumn! Of late I have walked but little over the hills and through the woods, my leisure being chiefly occupied with my boat, which I have now learned to manage with tolerable skill. Yesterday afternoon I made a voyage alone up the North Branch of Concord River. There was a strong west-wind blowing dead against me, which, together with the current, increased by the height of the water, made the first part of the passage pretty toilsome. The black river was all dimpled over with little eddies and whirlpools; and the breeze, moreover, caused the billows to beat against the bow of the boat, with a sound like the flapping of a bird’s wing. The water-weeds,where they were discernible through the tawny water, were straight outstretched by the force of the current, looking as if they were forced to hold on to their roots with all their might. If for a moment I desisted from paddling, the head of the boat was swept round by the combined might of wind and tide. However, I toiled onward stoutly, and, entering the North Branch, soon found myself floating quietly along a tranquil stream, sheltered from the breeze by the woods and a lofty hill. The current, likewise, lingered along so gently that it was merely a pleasure to propel the boat against it. I never could have conceived that there was so beautiful a river-scene in Concord as this of the North Branch. The stream flows through the midmost privacy and deepest heart of a wood, which, as if but half satisfied with its presence, calm, gentle, and unobtrusive as it is, seems to crowd upon it, and barely to allow it passage; for the trees are rooted on the very verge of the water, and dip their pendent branches into it. On one side there is a high bank, forming the side of a hill, the Indian name of which I have forgotten, though Mr. Thoreau told it to me; and here, in some instances, the trees stand leaning over the river, stretching out their arms as if about to plunge in headlong. On the other side, the bank is almost on a level with the water; and there the quiet congregation of trees stood with feet in the flood, and fringed with foliage down to its very surface. Vines here and there twine themselves about bushes or aspens or alder-trees, and hang their clusters (though scanty and infrequent this season) so that I can reach them from my boat. I scarcely remember a scene of more complete and lovely seclusion than the passage of the river through this wood. Even an Indian canoe, in oldentimes, could not have floated onward in deeper solitude than my boat. I have never elsewhere had such an opportunity to observe how much more beautiful reflection is than what we call reality. The sky, and the clustering foliage on either hand, and the effect of sunlight as it found its way through the shade, giving lightsome hues in contrast with the quiet depth of the prevailing tints,–all these seemed unsurpassably beautiful when beheld in upper air. But on gazing downward, there they were, the same even to the minutest particular, yet arrayed in ideal beauty, which satisfied the spirit incomparably more than the actual scene. I am half convinced that the reflection is indeed the reality, the real thing which Nature imperfectly images to our grosser sense. At any rate, the disembodied shadow is nearest to the soul.

There were many tokens of autumn in this beautiful picture. Two or three of the trees were actually dressed in their coats of many colors,–the real scarlet and gold which they wear before they put on mourning. These stood on low, marshy spots, where a frost has probably touched them already. Others were of a light, fresh green, resembling the hues of spring, though this, likewise, is a token of decay. The great mass of the foliage, however, appears unchanged; but ever and anon down came a yellow leaf, half flitting upon the air, half falling through it, and finally settling upon the water. A multitude of these were floating here and there along the river, many of them curling upward, so as to form little boats, fit for fairies to voyage in. They looked strangely pretty, with yet a melancholy prettiness, as they floated along. The general aspect of the river, however, differed but little from that of summer,–at least the differencedefies expression. It is more in the character of the rich yellow sunlight than in aught else. The water of the stream has now a thrill of autumnal coolness; yet whenever a broad gleam fell across it, through an interstice of the foliage, multitudes of insects were darting to and fro upon its surface. The sunshine, thus falling across the dark river, has a most beautiful effect. It burnishes it, as it were, and yet leaves it as dark as ever.

On my return, I suffered the boat to float almost of its own will down the stream, and caught fish enough for this morning’s breakfast. But, partly from a qualm of conscience, I finally put them all into the water again, and saw them swim away as if nothing had happened.

Nathaniel Hawthorne’s journal entry of September 18th, 1842

Geryon Transporting Dante and Virgil to Malasbolsas — William Blake

Read Shirley Jackson’s short story “Charles”

“Charles”

by

Shirley Jackson

The day my son Laurie started kindergarten he renounced corduroy overalls with bibs and began wearing blue jeans with a belt; I watched him go off the first morning with the older girl next door, seeing clearly that an era of my life was ended, my sweet-voiced nursery-school tot replaced by a long-trousered, swaggering character who forgot to stop at the corner and wave good-bye to me.

He came home the same way, the front door slamming open, his cap on the floor, and the voice suddenly become raucous shouting, “Isn’t anybody here?”

At lunch he spoke insolently to his father, spilled his baby sister’s milk, and remarked that his teacher said we were not to take the name of the Lord in vain.

“How was school today?” I asked, elaborately casual.

“All right,” he said.

“Did you learn anything?” his father asked.

Laurie regarded his father coldly. “I didn’t learn nothing,” he said.

“Anything,” I said.

“Didn’t learn anything”

“The teacher spanked a boy, though,” Laurie said, addressing his bread and butter. “For being fresh,” he added, with his mouth full.

“What did he do?” I asked. “Who was it?”

Laurie thought. “It was Charles,” he said. “He was fresh. The teacher spanked him and made him stand in a corner. He was awfully fresh.”

“What did he do?” I asked again, but Laurie slid off his chair, took a cookie, and left, while his father was still saying, “See here, young man.”

The next day Laurie remarked at lunch, as soon as he sat down, “Well, Charles was bad again today.” He grinned enormously and said, “Today Charles hit the teacher.”

“Good heavens,” I said, mindful of the Lord’s name, “I suppose he got spanked again?”

“He sure did,” Laurie said. “Look up,” he said to his father. “What?” his father said, looking up.

“Look down,” Laurie said. “Look at my thumb. Gee, you’re dumb.” He began to laugh insanely.

“Why did Charles hit the teacher?” I asked quickly.

“Because she tried to make him color with red crayons,” Laurie said. “Charles wanted to color with green crayons so he hit the teacher and she spanked him and said nobody play with Charles but everybody did.”

The third day—it was Wednesday of the first week—Charles bounced a see-saw on to the head of a little girl and made her bleed, and the teacher made him stay inside all during recess. Thursday Charles had to stand in a corner during storytime because he kept pounding his feet on the floor. Friday Charles was deprived of blackboard privileges because he threw chalk.

Geryon — Gustave Dore

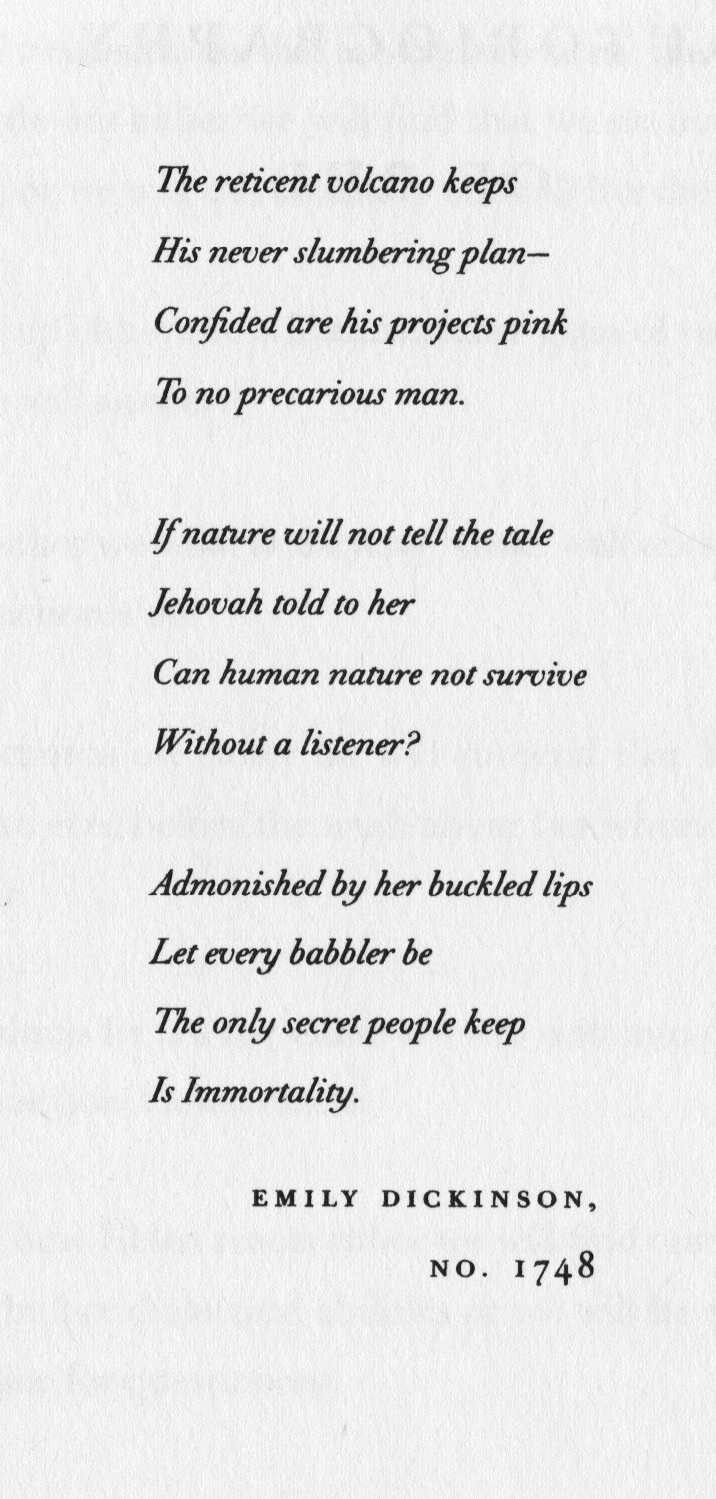

“The reticent volcano keeps” — Emily Dickinson

This Dickinson poem is a sort of epigraph to Anne Carson’s novel-poem-poem-novel Autobiography of Red. I had never read either, before today, somehow, but oh my electric!