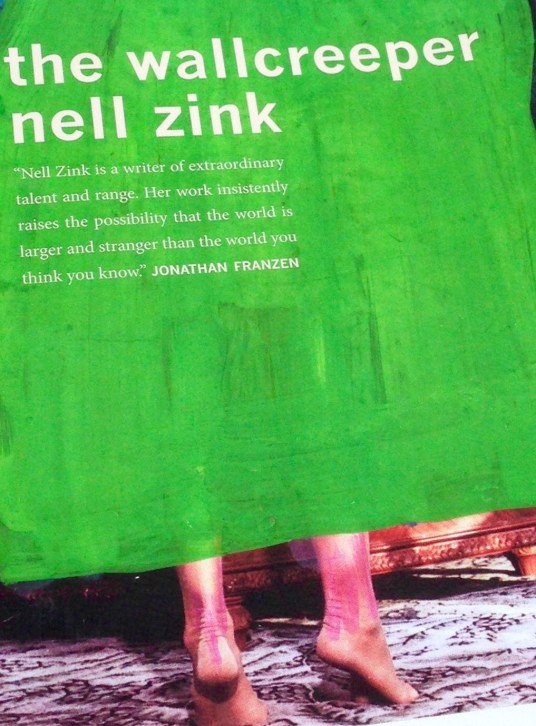

The short review is, “Nell Zink’s début novel The Wallcreeper is extraordinary.”

But this argument is insufficient, unsupported, you, dear reader, may protest. Why should you spend your hard-earned time reading The Wallcreeper, eh? (I read the book in four sittings. I was late to Sunday dinner for finishing the thing). To invert one of the better book short book reviews I’ve ever read: Every sentence made me want to read the next sentence. Is that not a good enough reason to read The Wallcreeper? Maybe you want to read some of those sentences. Here’s the first one:

I was looking at the map when Stephen swerved, hit the rock, and occasioned the miscarriage.

Or a page or two later when our heroine/narrator Tiffany describes how she met Stephen:

Our first meeting prevented a crime. He saw me standing in front of the open gate of the vault.

(Don’t worry about that crime). Oh, and, on that first meeting with Stephen:

It was one of those moments where you think: We will definitely fuck. It might take a while, though, because Stephen looked as respectable as I did.

And here’s a simile from Tiffany, just because I love the line and can wedge it in here:

After the cranes had landed, the geese passed overhead in so many Vs that they merged into Xs and covered the entire sky like a fishnet stocking.

It occurs to me now that I’m probably doing this wrong, right? I should be summarizing the book a bit, no? I’m not particularly interested in that—the plot is the sentences—I mean, yeah, there’s a plot, about Tiffany and Stephen in Berne and later Berlin—and some other places too—and the different lovers they take and the various projects they undertake—music, language acquisition, ecoterrorism—and lots of birdwatching.

Maybe I should lazily just reblurb Keith Gessen’s blurb:

Who is Nell Zink? She claims to be an expatriate living in northeast Germany. Maybe she is; maybe she isn’t. I don’t know. I do know that this first novel arrives with a voice that is fully formed: mature, hilarious, terrifyingly intelligent, and wicked. The novel is about a bird-loving American couple that moves to Europe and becomes, basically, eco-terrorists. This is strange, and interesting, but in between is some writing about marriage, love, fidelity, Europe, and saving the earth that is as funny and as grown-up as anything I’ve read in years. And there are some jokes in here that a young Don DeLillo would kill to have written. I hope he doesn’t kill Nell Zink

The DeLillo comparison is apt, but Zink’s novel is funnier than anything DeLillo’s done in ages. Maybe that’s not fair. “Funny” seems like a weak word, really, for Zink and her narrator Tiffany (and Stephen)—all the words I would use to describe what Zink’s doing here seem pale and imprecise. I mean witty, smart, intelligent, devastating, confounding. Extraordinary, right, that was the word I used above, yes? (He looks the word up in an online dictionary, somehow at 36 and a lifelong native English speaker unsure what it actually means). A placeholder like strange would work, except some of y’all take that word as a pejorative. Eccentric or quirky imply, I think, a rhetorical imprecision wholly absent from the novel. The Wallcreeper is a precise book. The book is very good. It is an interesting book. (What awful sentences those were! But true).

Can you know a book through the words the reviewer uses to describe it though? (No). Can you really know a character through the words she launches your way, anyway? In The Wallcreeper, Tiffany doesn’t really know herself, or Stephen, and the narrative is in some ways her kinda sorta finding out about herself (and Stephen, and other stuff), in a non-urgent manner. Or maybe very urgent, I don’t know—she and Stephen are in a constant state of crisis, sort of, or epiphany-making—

Our marriage had begun in the most daunting way imaginable. We had barely known each other, and then we had those accidents and that jarring disconnect between causes (empty-headed young people liking each other, wallcreepers) and effects (pain, death).

A wallcreeper is a small bird with crimson wings, by the way.

The titular wallcreeper, also by the way, is the thing that makes Stephen swerve in that opening sentence I shared for you above. The book is full of swerves, dips, dives, turns—each sentence swerves into the next, artfully, gracefully, precisely. Tiffany’s consciousness, or the language that Zink uses to represent Tiffany’s consciousness, swerves:

We walked down into the lower garden and sat on a bench. He looked into the pond and remarked favorably on the lack of goldfish. I thought of all the spawn-guzzling carp I had admired in the past and felt abashed. I shrank at the vulgarity of raptures over beauty, nature’s most irrelevant and unnecessary quality.

Beautiful!

But where was I? I think swerves was the metaphor I was batting about a bit—well, I suppose I could go on, suggest that all that swerving swerves up to Something More, that the novel swerves (swells? no, not swells) to an ending shot-through with mythical undertones (which our narrator punctures)—I mean to say that, yes, okay, the novel is a wonderful witty aesthetic read—each sentence made me want to read the next sentence—but readers who require More Than That will also get it. Or maybe not. The Wallcreeper, like all extraordinary novels, is Not For Everyone. The Wallcreeper was/is for me though, and I hope it will also be for you too.

The Wallcreeper is available directly from publisher The Dorothy Project and finer bookshops.

I’ve just started reading this and was equally captivated by all the sentences you just listed. It’s reminding me of Lydia Davis and Miranda July so far… can’t wait to read the rest!

LikeLike

I’m convinced–added it to my list.

LikeLike

I have to read this for an English seminar this upcoming semester and am now very excited!

LikeLike

[…] Nell Zink’s debut novel The Wallcreeper is fucking incredible. […]

LikeLike

[…] taking me a lot longer to get through than The Wallcreeper, maybe in large part because I’m reading it as an ebook, which means its competing with other […]

LikeLike

[…] with Marianne Fritz’s The Weight of Things), the publisher who brought us Nell Zink’s The […]

LikeLike

[…] The Wallcreeper, Nell Zink […]

LikeLike

[…] Nell Zink (although I liked The Wallcreeper better, but hey, it was published last […]

LikeLike