During that period of three months when I wrote reviews, reading ten or more books a week, I made a discovery: that the interest with which I read these books had nothing to do with what I feel when I read-let’s say—Thomas Mann, the last of the writers in the old sense, who used the novel for philosophical statements about life. The point is, that the function of the novel seems to be changing; it has become an outpost of journalism; we read novels for information about areas of life we don’t know-Nigeria, South Africa, the American army, a coal-mining village, coteries in Chelsea, etc. We read to find out what is going on. One novel in five hundred or a thousand has the quality a novel should have to make it a novel—the quality of philosophy. I find that I read with the same kind of curiosity most novels, and a book of reportage. Most novels, if they are successful at all, are original in the sense that they report the existence of an area of society, a type of person, not yet admitted to the general literate consciousness. The novel has become a function of the fragmented society, the fragmented consciousness. Human beings are so divided, are becoming more and more divided, and more subdivided in themselves, reflecting the world, that they reach out desperately, not knowing they do it, for information about other groups inside their own country, let alone about groups in other countries. It is a blind grasping out for their own wholeness, and the novel-report is a means towards it. Inside this country, Britain, the middle-class has no knowledge of the lives of the working-people, and vice-versa; and reports and articles and novels are sold across the frontiers, are read as if savage tribes were being investigated. Those fishermen in Scotland were a different species from the coalminers I stayed with in Yorkshire; and both come from a different world than the housing estate outside London. Yet I am incapable of writing the only kind of novel which interests me: a book powered with an intellectual or moral passion strong enough to create order, to create a new way of looking at life. It is because I am too diffused. I have decided never to write another novel. I have fifty ‘subjects’ I could write about; and they would be competent enough. If there is one thing we can be sure of, it is that competent and informative novels will continue to pour from the publishing houses. I have only one, and the least important of the qualities necessary to write at all, and that is curiosity. It is the curiosity of the journalist. I suffer torments of dissatisfaction and incompletion because of my inability to enter those areas of life my way of living, education, sex, politics, class bar me from. It is the malady of some of the best people of this time; some can stand the pressure of it; others crack under it; it is a new sensibility, a half-unconscious attempt towards a new imaginative comprehension. But it is fatal to art.

From Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook.

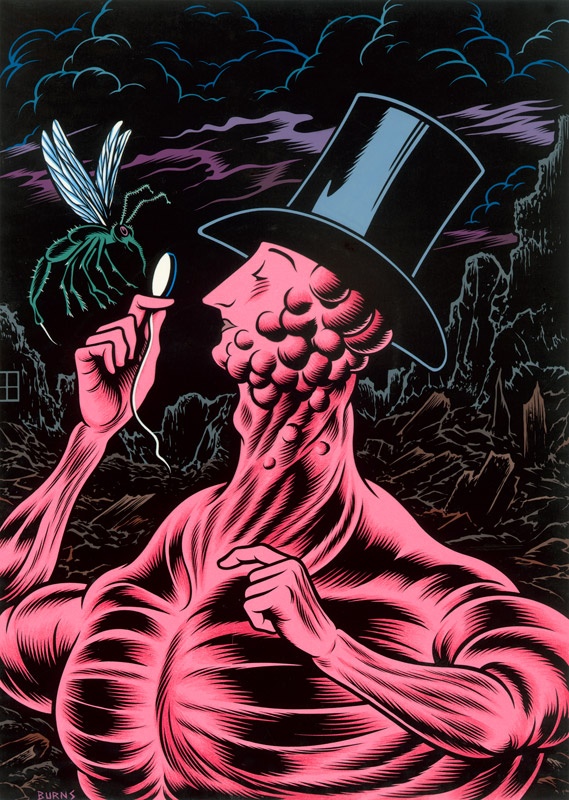

Kevin Thomas’s new book Horn! (from

Kevin Thomas’s new book Horn! (from