In the first chapter of his estimable volume The Book of Were-Wolves (1865), Sabine Baring-Gould outlines his project (emphasis mine):

In the following pages I design to investigate the notices of were-wolves to be found in the ancient writers of classic antiquity, those contained in the Northern Sagas, and, lastly, the numerous details afforded by the mediæval authors. In connection with this I shall give a sketch of modern folklore relating to Lycanthropy.

It will then be seen that under the veil of mythology lies a solid reality, that a floating superstition holds in solution a positive truth.

This I shall show to be an innate craving for blood implanted in certain natures, restrained under ordinary circumstances, but breaking forth occasionally, accompanied with hallucination, leading in most cases to cannibalism. I shall then give instances of persons thus afflicted, who were believed by others, and who believed themselves, to be transformed into beasts, and who, in the paroxysms of their madness, committed numerous murders, and devoured their victims.

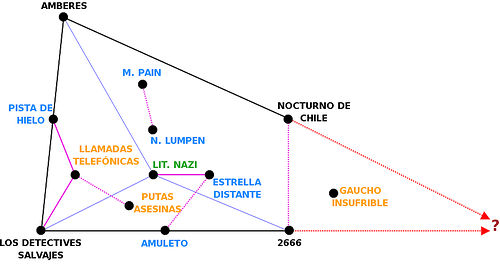

The first few chapters of the book recount werewolf mythology in heavily archetypal terms: we’re talking Greek and Norse stuff here, really ancient stories that tap into primal-human-animal-instinct and so forth. Then there are a few chapters on Scandinavian werewolves (and other shapeshifters) that reminded me of William Vollmann’s marvelous saga The Ice-Shirt, a book that treats warriors shifting into bears as totally standard fare. The book then tackles “The Were-Wolf in the Middle Ages,” where Baring-Gould relies heavily on monks who seem to view their subject through the heady lens of supernaturalism. Baring-Gould weaves together these culturally disparate stories, citing a strong backlist of sources, and refraining from pointing out the obvious archetypal flavor that girds these tales.

It’s in Chapter VI, “A Chamber of Horrors,” that mythology and archetype give way to a kind of terrible realism. Perhaps this is simply an effect of records-keeping, of the vague fact that narratives and terms of the early Renaissance seem so much more accessible to us than, say, the terms of Scandinavian saga. In any case, the book takes on a horrific scope: the vagaries of myth give way to dates, names, places, witnesses, trials, verdicts. To go back to Baring-Gould’s intro, we see the “solid reality” under “the veil of mythology,” stripped away.

An example to illustrate — “A Chamber of Horrors” begins:

In December, 1521, the Inquisitor-General for the diocese of Besançon, Boin by name, heard a case of a sufficiently terrible nature to produce a profound sensation of alarm in the neighbourhood. Two men were under accusation of witchcraft and cannibalism. Their names were Pierre Bourgot, or Peter the Great, as the people had nicknamed him from his stature, and Michel Verdung. Peter had not been long under trial, before he volunteered a full confession of his crimes. It amounted to this:–

In the interest of time and space, I’ll break from Baring-Gould’s summary of the Inquisitor General’s record of Peter the Great’s confession to quickly summarize: There are several pages detailing the ritual circumstances of Peter and Michel’s initial transmogrifications into werebeasts, including some early kills. Let’s skip ahead to some grisly details:

In one of his were-wolf runs, Pierre fell upon a boy of six or seven years old, with his teeth, intending to rend and devour him, but the lad screamed so loud that he was obliged to beat a retreat to his clothes, and smear himself again, in order to recover his form and escape detection. He and Michel, however, one day tore to pieces a woman as she was gathering peas; and a M. de Chusnée, who came to her rescue, was attacked by them and killed.

On another occasion they fell upon a little girl of four years old, and ate her up, with the exception of one arm. Michel thought the flesh most delicious. Another girl was strangled by them, and her blood lapped up. Of a third they ate merely a portion of the stomach.

One evening at dusk, Pierre leaped over a garden wall, and came upon a little maiden of nine years old, engaged upon the weeding of the garden beds. She fell on her knees and entreated Pierre to spare her; but he snapped the neck, and left her a corpse, lying among her flowers. On this occasion he does not seem to have been in his wolf’s shape. He fell upon a goat which he found in the field of Pierre Lerugen, and bit it in the throat, but he killed it with a knife.

Michel was transformed in his clothes into a wolf, but Pierre was obliged to strip, and the metamorphosis could not take place with him unless he were stark naked. He was unable to account for the manner in which the hair vanished when he recovered his natural condition.

I’ve given this example at some length as it’s a fairly representative passage. To be clear, Baring-Gould goes on for pages and pages and pages of this stuff, bringing up example after example of murderers and their victims and the villages and cities that prosecute them (you can read the book for free, if you wish—it’s in the public domain). It’s ugly and depressing, and one gets the picture that the kind of psychopathic homicidal behavior we often think of as pervasive in and native to the 20th and 21st centuries is actually far, far older. Pierre Bourgot and Michel Verdung are earlier instantiations of Henry Lee Lucas and Ottis Toole or Leopold and Loeb or any of the other partners in crime we might think of.

But not all these werewolves work in pairs. There’s the case of Jean Grenier, who gets his own chapter. A description of Grenier as a boy of about 13:

The appearance of the lad was peculiar. His hair was of a tawny red and thickly matted, falling over his shoulders and completely covering his narrow brow. His small pale-grey eyes twinkled with an expression of horrible ferocity and cunning, from deep sunken hollows. The complexion was of a dark olive colour; the teeth were strong and white, and the canine teeth protruded over the lower lip when the mouth was closed. The boy’s hands were large and powerful, the nails black and pointed like bird’s talons. He was ill clothed, and seemed to be in the most abject poverty. The few garments he had on him were in tatters, and through the rents the emaciation of his limbs was plainly visible.

Baring-Gould’s gift for detail—a gift bequeathed in part, one gathers, from trial testimonies and other criminal records—presents the ambiguity of Grenier. The boy is clearly a case of neglect who slips into madness and murder. Baring-Gould also has a gift for dialogue. Here, Grenier terrorizes some fair innocent maidens:

“Well, my maidens,” said he in a harsh voice, “which of you is the prettiest, I should like to know; can you decide among you?”

“What do you want to know for?” asked Jeanne Gaboriant, the eldest of the girls, aged eighteen, who took upon herself to be spokesman for the rest.

“Because I shall marry the prettiest,” was the answer.

“Ah!” said Jeanne jokingly; “that is if she will have you, which is not very likely, as we none of us know you, or anything about you.”

“I am the son of a priest,” replied the boy curtly.

“Is that why you look so dingy and black?”

“No, I am dark-coloured, because I wear a wolf-skin sometimes.”

“A wolf-skin!” echoed the girl; “and pray who gave it you?”

“One called Pierre Labourant.”

“There is no man of that name hereabouts. Where does he live?”

A scream of laughter mingled with howls, and breaking into strange gulping bursts of fiendlike merriment from the strange boy. The little girls recoiled, and the youngest took refuge behind Jeanne.

“Do you want to know Pierre Labourant, lass? Hey, he is a man with an iron chain about his neck, which he is ever engaged in gnawing. Do you want to know where he lives, lass? Ha., in a place of gloom and fire, where there are many companions, some seated on iron chairs, burning, burning; others stretched on glowing beds, burning too. Some cast men upon blazing coals, others roast men before fierce flames, others again plunge them into caldrons of liquid fire.”

The terrible scene continues in this vein, building dread until the poor girls (sensibly) flee.

Grenier takes off on a murderous, cannibalistic spree, before being apprehended and “sentenced . . . to perpetual imprisonment within the walls of a monastery at Bordeaux, where he might be instructed in his Christian and moral obligations.”

The monastery—the asylum—is the kind of place where many if not most of these convicted werewolves end up. I’ve neglected to share Baring-Gould’s definition of lycanthropy, which also telegraphs part of his thesis (emphasis, again, is mine):

What is Lycanthropy? The change of man or woman into the form of a wolf, either through magical means, so as to enable him or her to gratify the taste for human flesh, or through judgment of the gods in punishment for some great offence. This is the popular definition.

Truly it consists in a form of madness, such as may be found in most asylums.

We see here that Baring-Gould’s project is to strip away the supernaturalism—indeed the glamor—of the werewolf to root out the all-too-human madness underneath.

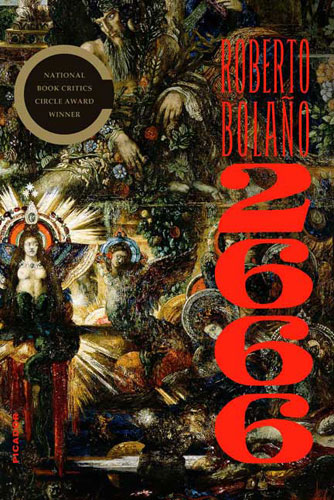

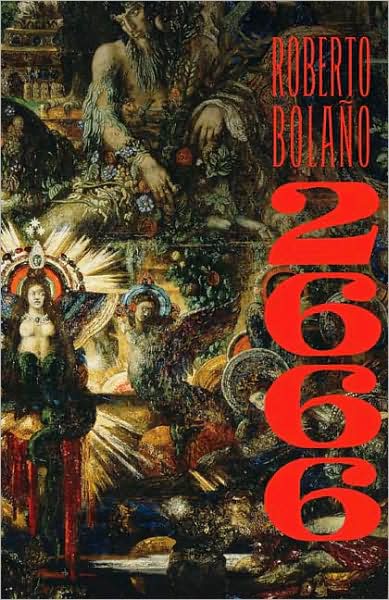

Perhaps I’ve taken too long to connect Baring-Gould to the work of Roberto Bolaño, but I felt the need to set the stage and share some of Baring-Gould’s language, which, to be clear, I believe prefigures Bolaño’s own work in many ways. I am not suggesting that Bolaño read Baring-Gould, only that the realistic documentation of grisly murder and madness in The Book of Were-Wolves evinces throughout the Bolañoverse, particularly in 2666, from which I will draw my examples in this essay.

What Bolaño and Baring-Gould do in these books is explore madness and violence and the ways that our world tries to (or fails to) contain madness and violence.

If you’ve read 2666, you’ll likely note that Baring-Gould’s descriptions and even tone resonates strongly with “The Part About the Crimes,” a grisly catalog of murder and violence (even Baring-Gould’s chapter title “A Chamber of Horrors” seems to correspond). To be sure, both writers employ a frank, almost reportorial tone that often clashes against lucid nightmare details—there’s a heavy dose of unreality that poses as a kind of cure, almost, to the poisoned reality of mutilated bodies.

Maybe another way of approaching this is to point out how heavily the werewolves of Baring-Gould and Bolaño contrast with the glamorous, sexy werewolves of, say, True Blood or Twilight, werewolves that clearly tap into the mythos and psychology of transformation while at the same time sundering that transformative possibility away from any plain old Joe Schmo’s aptitude for grisly violence.

I’ve just referred to Bolaño’s werewolves—it’s also the title of this essay, so “just referred” is hardly accurate—so I should point out that the word werewolf never occurs in 2666.

What I want to suggest is that Bolaño’s werewolves are, in line with Baring-Gould’s, people fated to madness and violence, but also relatively normal people. These werewolves contain within them a dreadful capacity for violence.

The litany of evil in “The Part About Crimes,” as I’ve already suggested, showcases werewolf work: the mutilated bodies, the rape, the awful mystery of it all. There are even a few references to wolf transformations (of a kind). Here’s a late one:

Something ugly happened here, said the border patrol, but since there were no bodies, the whole thing was easy to write off. What did Ayala do with the bodies? According to El Tequila, he ate them, that’s how crazy and evil he was, although Haas doubted there was anyone capable of wolfing down eight illegal immigrants, no matter how demented or ravenous he might be.

I won’t torture the scene into something it’s not, but we see here the possibility—in language—of the criminal El Tequila “wolfing” down his victims in an act of cannibalism.

Or, this scene, where Epifanio Galinda, one of the few heroes of “The Part About the Crimes” believes he’s killed a wolf:

I killed a wolf, he said. Let’s see, said the police chief, and the two of them set out into the darkness again. There were no headlights visible on the highway. The air was dry but sometimes there were gusts of salty wind, as if before it made its way into the desert the air had brushed across a salt marsh. The boy looked at the lighted dashboard of the car and then he covered his face with his hands. A few yards away the police chief ordered Epifanio to pass him the flashlight and he shone it on the body of the animal lying in the road. It isn’t a wolf, said the police chief. Oh, no? Look at its coat, wolves’ coats are shinier, sleeker, not to mention they aren’t dumb enough to get themselves run over by a car in the middle of a deserted highway. Let’s see, let’s measure it, you hold the flashlight. Epifanio trained the beam on the animal as the chief laid it straight and eyeballed it. Coyotes, he said, are twenty-eight to thirty-six inches long, counting the head. What would you say this one measures? About thirty-two? asked Epifanio. Correct, said the police chief. And he went on: coyotes weigh between twenty-two and thirty-five pounds. Pass me the flashlight and pick it up, it won’t bite you. Epifanio picked up the dead animal, cradling it in his arms. How much would you say it weighs? Somewhere between twenty-six and thirty-three, maybe, said Epifanio. Like a coyote. Because it is a coyote, jackass, said the police chief.

The term coyote of course has its own associations in borderland—it’s a pejorative term for the men who smuggle immigrants into the U.S. Epifanio’s would-be wolf, symbol of predation and murder, morphs under closer analysis into another, subtler predator.

But I’m not particularly interested in literal wolves or even the metaphorical use of the word wolf in this discussion of 2666 and The Book of Were-Wolves. Again, what I think germane here is Bolaño’s ability to document the capacity of insanity and violence that lurks in each and every person—that is what the werewolf is. We can see the werewolf when we strip away what Baring-Gould calls “the veil of mythology,” the “floating superstition” that would otherwise explain away the secrets of evil.

Here’s a detail from the first few pages of 2666, from “The Part About the Critics”:

[Espinoza] also discovered that he was bitter and full of resentment, that he oozed resentment, and that he might easily kill someone, anyone . . .

The line seems almost casual so early in the text. It’s not necessarily forgettable, but it’s also not especially noteworthy—that is, until you work your way through the labyrinth of 2666 a second or third time. In a course of rereading, Espinoza’s murderous urge becomes not just a simple expression, but a genuine threat.

“The Part About the Critics” is, in some ways, the least obviously lycanthropic chapter of 2666, and hence all the more important to my (admittedly cloudy) thesis. I’m going to devote the rest of my energy solely to “Critics,” but first I’ll sweep over the rest of the book.

“The Part About Amalfitano” documents a descent into madness, and if its motif relies more on ghosts than werewolves, I’d still like to submit Marco Antonio Guerra as the worst kind of would-be werewolf, a youth primed for insane back alley violence of every stripe. He is pure Bolaño-sinister, a character from the shady margins of a Lynch film. When he tells Amalfitano that, “the human being, broadly speaking, is the closest thing there is to a rat,” his statement is all the more believable because he is, of course, a wererat.

“The Part About Fate” twins “Amalfitano,” similarly documenting descent into madness; its special werewolf—maybe more a vampire, to be fair—is Chucho Flores.

I’ve already remarked on “The Part About the Crimes.”

“The Part About Archimboldi,” with its Gothic scenes and numerous Dracula references perhaps skews more vampire again, but let’s just lump these supernatural predators together for now. Suffice to point out that Baring-Gould frequently reminds his audience that “the were-wolf is closely related to the vampire.” He continues:

The lycanthropist falls into a cataleptic trance, during which his soul leaves his body, enters that of a wolf and ravens for blood. On the return of the soul, the body is exhausted and aches as though it had been put through violent exercise. After death lycanthropists become vampires. They are believed to frequent battlefields in wolf or hyæna shapes, and to suck the breath from dying soldiers, or to enter houses and steal the infants from their cradles.

Back to “The Part About the Critics”: The first time I read 2666, I thought of the “Critics” as a light, even romantic entry point to the novel—a sort of romantic quadrangle with ironic self-awareness. Subsequent readings reveal an extremely dark work, one that repeatedly hides its darkness, or shifts quickly away from it, as when the critic Morini reads about the Sonora killings that will figure so heavily in “Crimes” in a newspaper and only an hour later forgets the matter completely.

But that murderous violence is always there, seething under the surface, as in that early description of Espinoza, or in this description from early in the book, one of the first labyrinthine nesting doll tales, where the Swabian relates a story related to him by an old woman of a visit to Buenos Aires and her encounter with a strange ranch-hand:

. . . the little gaucho looked up at the lady with the eyes of a bird of prey, ready to plunge a knife into her at the navel and slice up to the breasts, cutting her wide open, his eyes shining with a strange intensity, like the eyes of a clumsy young butcher, as the lady recalled, which didn’t stop her from following him without protest when he took her by the hand and led her to the other side of the house, to a place where a wrought-iron pergola stood, bordered by flowers and trees that the lady had never seen in her life or which at that moment she thought she had never seen in her life, and she even saw a fountain in the park, a stone fountain, in the center of which, balanced on one little foot, a Creole cherub with smiling features danced, part European and part cannibal, perpetually bathed by three jets of water that spouted at its feet, a fountain sculpted from a single piece of black marble, a fountain that the lady and the little gaucho admired at length . . .

Everything in that New World “part European and part cannibal.” The aesthetics of the episode devour or at least mask the little gaucho’s violence, his ability to transform into a murderous beast.

The critics who hear this story from the Swabian represent some of the old, dignified cultures of Europe—French, Italian, English, Spanish; they are erudite academics, situated above the dirty meaningless violence that litters the rest of the book.

Of course, Bolaño absolutely ridicules this notion, evoking the critics’ own dispositions to violence.

Here’s a passage that illustrates Bolaño’s lycanthropic powers. In this little episode, Pelletier and Espinoza—both in love and lust with fellow critic Norton—share a cab with her during a visit to London. I quote at some length:

And for the first few minutes, the driver, a Pakistani, watched them in his rearview mirror, in silence, as if he couldn’t believe what his ears were hearing, and then he said something in his language and the cab passed Harmsworth Park and the Imperial War Musuem, heading along Brook Drive and then Austral Street and then Geraldine Street, driving around the park, an unnecessary maneuver no matter how you looked at it. And when Norton told him he was lost and said which streets he should take to find his way, the driver fell silent again, with no more murmurings in his incomprehensible tongue, until he confessed that London was such a labyrinth, he really had lost his bearings.

Which led Espinoza to remark that he’d be damned if the cabbie hadn’t just quoted Borges, who once said London was like a labyrinth— unintentionally, of course. To which Norton replied that Dickens and Stevenson had used the same trope long before Borges in their descriptions of London. This seemed to set the driver off, for he burst out that as a Pakistani he might not know this Borges, and he might not have read the famous Dickens and Stevenson either, and he might not even know London and its streets as well as he should, that’s why he’d said they were like a labyrinth, but he knew very well what decency and dignity were, and by what he had heard, the woman here present, in other words Norton, was lacking in decency and dignity, and in his country there was a word for what she was, the same word they had for it in London as it happened, and the word was bitch or slut or pig, and the gentlemen who were present, gentlemen who, to judge by their accents, weren’t English, also had a name in his country and that name was pimp or hustler or whoremonger.

This speech, it may be said without exaggeration, took the Archimboldians by surprise, and they were slow to respond. If they were on Geraldine Street when the driver let them have it, they didn’t manage to speak till they came to Saint George’s Road. And then all they managed to say was: stop the cab right here, we’re getting out. Or rather: stop this filthy car, we’re not going any farther. Which the Pakistani promptly did, punching the meter as he pulled up to the curb and announcing to his passengers what they owed him, a fait accompli or final scene or parting token that seemed more or less normal to Norton and Pelletier, no doubt still reeling from the ugly surprise, but which was absolutely the last straw for Espinoza, who stepped down and opened the driver’s door and jerked the driver out, the latter not expecting anything of the sort from such a well-dressed gentleman. Much less did he expect the hail of Iberian kicks that proceeded to rain down on him, kicks delivered at first by Espinoza alone, but then by Pelletier, too, when Espinoza flagged, despite Norton’s shouts at them to stop, despite Norton’s objecting that violence didn’t solve anything, that in fact after this beating the Pakistani would hate the English even more, something that apparently mattered little to Pelletier, who wasn’t English, and even less to Espinoza, both of whom nevertheless insulted the Pakistani in English as they kicked him, without caring in the least that he was down, curled into a ball on the ground, as they delivered kick after kick, shove Islam up your ass, which is where it belongs, this one is for Salman Rushdie (an author neither of them happened to think was much good but whose mention seemed pertinent), this one is for the feminists of Paris (will you fucking stop, Norton was shouting), this one is for the feminists of New York (you’re going to kill him, shouted Norton), this one is for the ghost of Valerie Solanas, you son of a bitch, and on and on, until he was unconscious and bleeding from every orifice in the head, except the eyes.

When they stopped kicking him they were sunk for a few seconds in the strangest calm of their lives. It was as if they’d finally had the menage a trois they’d so often dreamed of.

Pelletier felt as if he had come. Espinoza felt the same, to a slightly different degree. Norton, who was staring at them without seeing them in the dark, seemed to have experienced multiple orgasms. A few cars were passing by on St. George’s Road, but the three of them were invisible to anyone traveling in a vehicle at that hour. There wasn’t a single star in the sky. And yet the night was clear: they could see everything in great detail, even the outlines of the smallest things, as if an angel had suddenly clapped night-vision goggles on their eyes. Their skin felt smooth, extremely soft to the touch, although in fact the three of them were sweating. For a moment Espinoza and Pelletier thought they’d killed the Pakistani. A similar idea seemed to be passing through Norton’s mind, because she bent over the cabbie and felt for his pulse. To move, to kneel down, hurt her as if the bones of her legs were dislocated.

The scene shifts from erudite literary reference to sadistic violence, with strange interruptions of very dark humor (I am ashamed that the first time I read this passage it made me laugh out loud in places—the line about Rushdie, in particular), ending in whorl that directly connects the violence to (extremely satisfying) sex. In short, it underlines the lurid, inexplicable violence (and interwoven sexuality) capable of erupting in even the most apparently staid people (think of the poor driver who would never expect expect violence “of the sort from such a well-dressed gentleman”). Bolaño’s project, like Baring-Gould’s, is to cut through the mythologies of transformation and violence to plumb the visceral nightmare of reality underneath.

Let’s return to that last part of Baring-Gould’s definition of lycanthropy: “Truly it consists in a form of madness, such as may be found in most asylums.”

Need I remark on the asylums of 2666?

The word asylum appears 43 times in the text.

The word prison 164.

Labyrinth 14.

Madness 29.

Lunatic 21.

Abyss 22.

You get the picture.

I’ll end then with a minor character of 2666, a minor werewolf I suppose, whose predation is perhaps limited to himself. In “The Part About the Critics,” we learn of the artist Edwin Johns who “cut off his painting hand” and then incorporated it into a self-portrait:

This painting, viewed properly (although one could never be sure of viewing it properly), was an ellipsis of self-portraits, sometimes a spiral of self-portraits (depending on the angle from which it was seen), seven feet by three and a half feet, in the center of which hung the painter’s mummified right hand.

Edwin Johns’s madness leads him to self-mutilation, but his violence is also bizarrely controlled and, well, artistic. It lands him in an asylum of course (where he meets some of the critics), but it also helps create his defining work, described as a kind of elliptical, abyssal spiral at the center of which is suspended the very instrument that created the work itself. Johns’s mummified hand perhaps represents a kind of purity of self, an act of self-negation that paradoxically preserves a self. It’s a transformation that leaves a pure trace (which, sundered, is impure, incomplete). It simultaneously makes and breaks Johns, confers his identity (as that artist who cut his hand off) and takes it away, pushing him into an asylum where he can presumably do no more harm to himself. And how does Johns die? We learn that he falls off a mountain — “he fell into the abyss.” Complete self-erasure, the finishing touch on his strange self-portrait.

But I seem to have jumped into my own little abyss here, or at least written myself into an ill-defined corner, one that provides no clean surface to rest my back against (in any case, I’m jumbling metaphors here).

Maybe I’m just trying to recommend Baring-Gould’s strange ghoulish book.

Maybe I’m just taking another stab at writing about 2666.

Maybe I just have werewolves on the brain.

Maybe it’s germane to all of this that I’ve been reading the books in a weird kind of tandem switch-hitting rhythm in the deep dark of night, said books nestled neatly on the low glow of my trusty Kindle.

Maybe it’s just that Baring-Gould gives us an answer to the murder-mystery 2666 is sometimes supposed to be, an answer that I perhaps like so much because I proposed it in my first review of the book.

Who killed all those women in Sonora?

Why, we all did it.

I’ve quoted Bolaño at length in this piece, so I’ll give the last words—again at some length—to Sabine Baring-Gould.

Here, he describes—but makes no attempt to explain away—the pleasure we may take in cruelty:

Startling though the assertion may be, it is a matter of fact, that man, naturally, in common with other carnivora, is actuated by an impulse to kill, and by a love of destroying life.

It is positively true that there are many to whom the sight of suffering causes genuine pleasure, and in whom the passion to kill or torture is as strong as any other passion. Witness the number of boys who assemble around a sheep or pig when it is about to be killed, and who watch the struggle of the dying brute with hearts beating fast with pleasure, and eyes sparkling with delight. Often have I seen an eager crowd of children assembled around the slaughterhouses of French towns, absorbed in the expiring agonies of the sheep and cattle, and hushed into silence as they watched the flow of blood.

The propensity, however, exists in different degrees. In some it is manifest simply as indifference to suffering, in others it appears as simple pleasure in seeing killed, and in others again it is dominant as an irresistible desire to torture and destroy.

This propensity is widely diffused; it exists in children and adults, in the gross-minded and the refined., in the well-educated and the ignorant, in those who have never had the opportunity of gratifying it, and those who gratify it habitually, in spite of morality, religion, laws, so that it can only depend on constitutional causes.

The sportsman and the fisherman follow a natural instinct to destroy, when they make wax on bird, beast, and fish: the pretence that the spoil is sought for the table cannot be made with justice, as the sportsman cares little for the game he has obtained, when once it is consigned to his pouch. The motive for his eager pursuit of bird or beast must be sought elsewhere; it will be found in the natural craving to extinguish life, which exists in his soul. Why does a child impulsively strike at a butterfly as it flits past him? He cares nothing for the insect when once it is beaten down at his feet, unless it be quivering in its agony, when he will watch it with interest. The child strikes at the fluttering creature because it has life in it, and he has an instinct within him impelling him to destroy life wherever he finds it.

Parents and nurses know well that children by nature are cruel, and that humanity has to be acquired by education. A child will gloat over the sufferings of a wounded animal till his mother bids him “put it out of its misery.” An unsophisticated child would not dream of terminating the poor creature’s agonies abruptly, any more than he would swallow whole a bon-bon till he had well sucked it. Inherent cruelty may be obscured by after impressions, or may be kept under moral restraint; the person who is constitutionally a Nero, may scarcely know his own nature, till by some accident the master passion becomes dominant, and sweeps all before it. A relaxation of the moral check, a shock to the controlling intellect, an abnormal condition of body, are sufficient to allow the passion to assert itself.

As I have already observed, this passion exists in different persons in different degrees.