I am glad I reread Nathaniel Hawthorne’s 1852 novel for many reasons. One of those reasons is because I had completely forgotten to remember a marvelous scene near the end of the novel, in Ch. XXV — “The Masqueraders.” This episode happens near the end of the chapter. Hawthorne’s stand-in Miles Coverdale has decided to return to Blithedale after spending some time out in, like, the world.

Coverdale’s return to the utopian project he half-heartedly abandoned is thoroughly coded in Hawthorne’s signature ambivalence: He notes “a sickness of the spirits kept alternating with my flights of causeless buoyancy” as he walks through the wood. Approaching the Blithedale farm, and feels an “invincible reluctance” in his return, which causes him to linger in the forest. By and by, as the lovely transitional phrase goes, Coverdale winds his way back to his “hermitage, in the heart of the white-pine tree.” (The white-pine reference strikes me as an oblique reference here to Hawthorne himself—or rather, a nod to a distinction between white pine and black hawthorn trees, alter egos).

Here in his hermitage he rests among grapes dangling in “abundant clusters of the deepest purple, deliciously sweet to the taste.” Coverdale’s hermitage is an idealized, natural—transcendental—version of Blithedale, the grapevines (a prefiguration of communication in the American parlance) a kind of perfectly polygamous knot of communal existence.

Taken up in solo-bacchanalia, Coverdale begins devouring the grapes. Always the loner, always the voyeur, he checks out the house from his arboreal perch and notes its emptiness. He decides, drunken on sweet grapes, to skulk through the woods, where he hears “Voices, male and feminine; laughter, not only of fresh young throats, but the bass of grown people.” He continues—

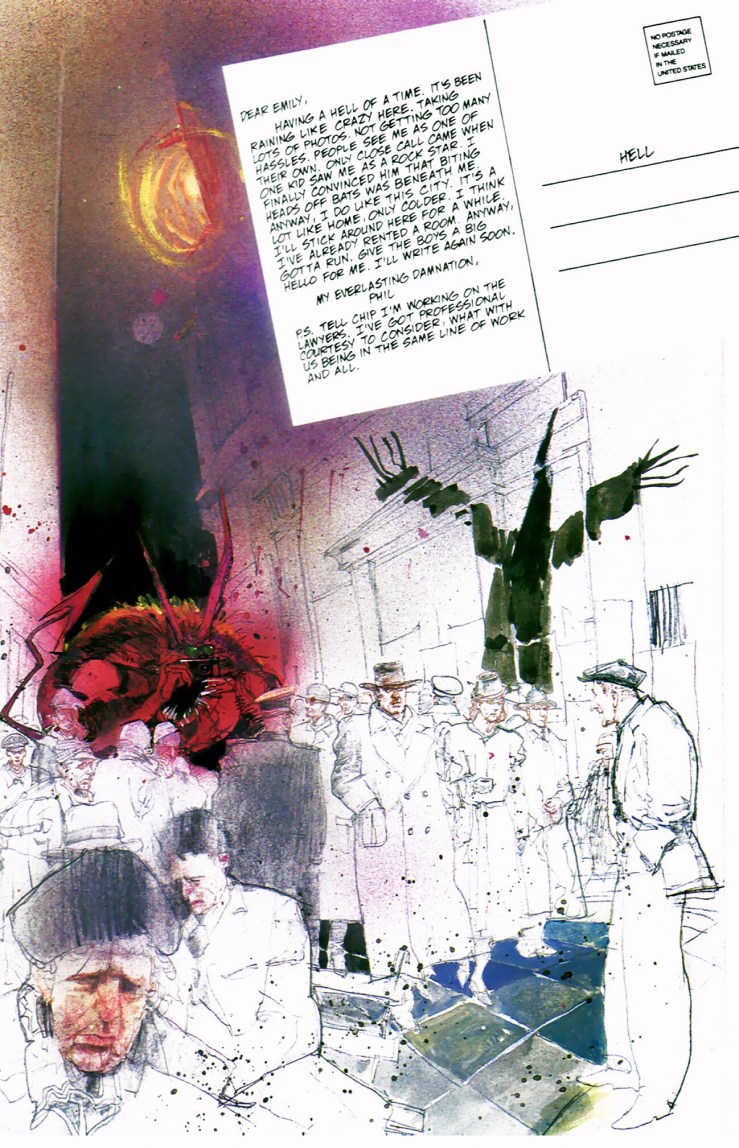

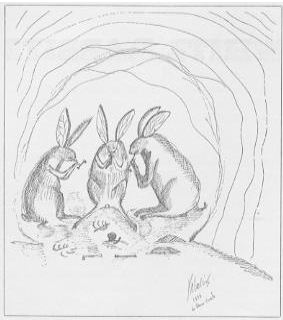

The wood, in this portion of it, seemed as full of jollity as if Comus and his crew were holding their revels in one of its usually lonesome glades. Stealing onward as far as I durst, without hazard of discovery, I saw a concourse of strange figures beneath the overshadowing branches. They appeared, and vanished, and came again, confusedly with the streaks of sunlight glimmering down upon them.

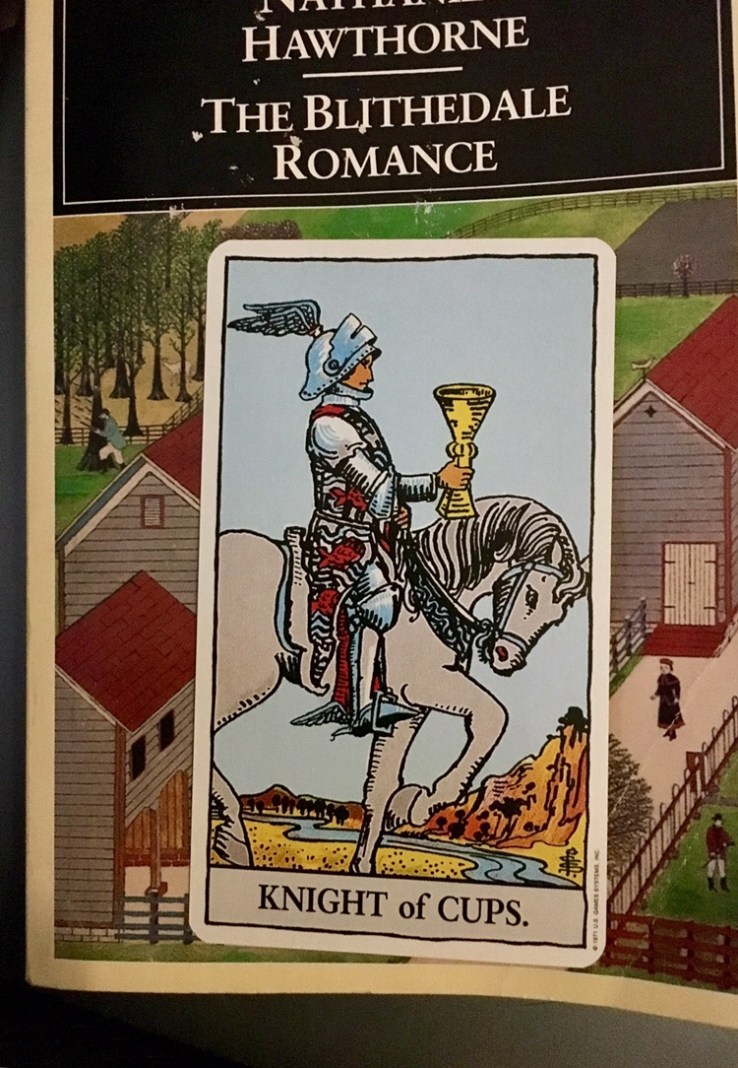

“Comus and his crew” — what a lovely evocation! Comus, cup-bearer and heir of Bacchus, is a figuration of erotic chaos. Hawthorne ushers his hero into a scene of pastoral American anarchy, a strange Arcadia that Walt Whitman would try to replicate in Leaves of Grass a few years later. Note the admixture of cultures here in Hawthorne’s transcendentalist Halloween:

Among them was an Indian chief, with blanket, feathers, and war-paint, and uplifted tomahawk; and near him, looking fit to be his woodland bride, the goddess Diana, with the crescent on her head, and attended by our big lazy dog, in lack of any fleeter hound. Drawing an arrow from her quiver, she let it fly at a venture, and hit the very tree behind which I happened to be lurking. Another group consisted of a Bavarian broom-girl, a negro of the Jim Crow order, one or two foresters of the Middle Ages, a Kentucky woodsman in his trimmed hunting-shirt and deerskin leggings, and a Shaker elder, quaint, demure, broad-brimmed, and square-skirted. Shepherds of Arcadia, and allegoric figures from the “Faerie Queen,” were oddly mixed up with these. Arm in arm, or otherwise huddled together in strange discrepancy, stood grim Puritans, gay Cavaliers, and Revolutionary officers with three-cornered cocked hats, and queues longer than their swords. A bright-complexioned, dark-haired, vivacious little gypsy, with a red shawl over her head, went from one group to another, telling fortunes by palmistry; and Moll Pitcher, the renowned old witch of Lynn, broomstick in hand, showed herself prominently in the midst, as if announcing all these apparitions to be the offspring of her necromantic art.

Again though, in classic Hawthorne fashion, our author hedges all bets, tempering his mythical romantic flight in skepticism, here embodied by Silas Foster, the only real farmer (real earthworker) of Blithedale:

But Silas Foster, who leaned against a tree near by, in his customary blue frock and smoking a short pipe, did more to disenchant the scene, with his look of shrewd, acrid, Yankee observation, than twenty witches and necromancers could have done in the way of rendering it weird and fantastic.

Our narrator Coverdale also spies some men “with portentously red noses…spreading a banquet on the leaf-strewn earth; while a horned and long-tailed gentleman” tuning up a fiddle. The end result:

So they joined hands in a circle, whirling round so swiftly, so madly, and so merrily, in time and tune with the Satanic music, that their separate incongruities were blended all together, and they became a kind of entanglement that went nigh to turn one’s brain with merely looking at it.

The entanglement here—which eventually explodes in riotous communal laughter—recalls the polygamous knot of grapevines that shrouded Coverdale’s hermitage.

The great laughter prompts Coverdale to explode in his own laughter, whereupon the Bacchic party sets out after him with comic-murderous intent:

“Some profane intruder!” said the goddess Diana. “I shall send an arrow through his heart, or change him into a stag, as I did Actaeon, if he peeps from behind the trees!”

Coverdale flees.

He eventually happens upon an old rotting woodpile covered in moss, where he daydreams about “the long-dead woodman, and his long-dead wife and children, coming out of their chill graves, and essaying to make a fire with this heap of mossy fuel!” — this before finally giving himself up to the Blithedale crew.

The episode strikes me very much as a sequel or reboot of Hawthorne’s 1835 story “Young Goodman Brown,” in which a Puritan naif wonders into the woods dark and deep and witnesses all the horrors of his young country made real—he sees the dark heart of his community beating naked and bloody and raw and Satanic—and it changes him forever, essentially dulling his soul unto a living death. The American Arcadia episode of Blithedale though is a bit richer in its mythos, its paganism more complex and inclusive, its perspective character more attuned to the vibrant possibilities of a transcendental community, even as he stands on its outside—and what is an outsider but the most vital secret ingredient of any community?