“Yesterday I dreamed about Thea von Harbou. . . . It woke me right up. . . . But then, thinking about it, I realized that I dreamed about her because of a novel I read recently. . . . It’s not that it was such a strange book, but I got the idea that the author was hiding something. . . . And after the dream, I figured it out . . .”

“What novel?”

“Silhouette, by Gene Wolfe.”

“. . .”

“Want me to tell you what it’s about?”

“All right, while I’m making breakfast.”

“I had some tea before, when you were asleep.”

“I’ve got a headache. Are you going to want another cup of tea?”

“Yes.”

“Go on. I’m listening, even if my back is turned.”

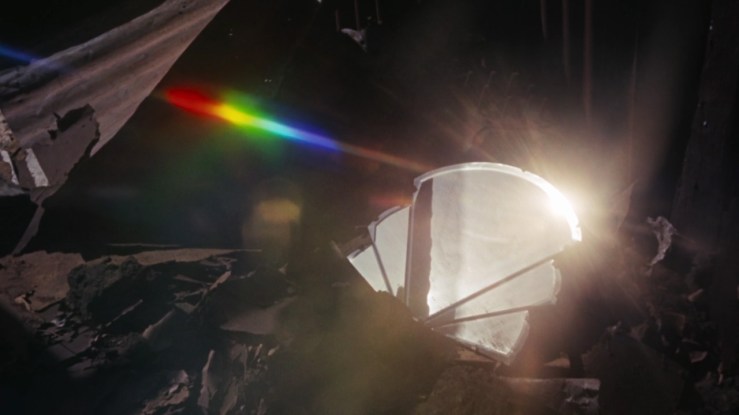

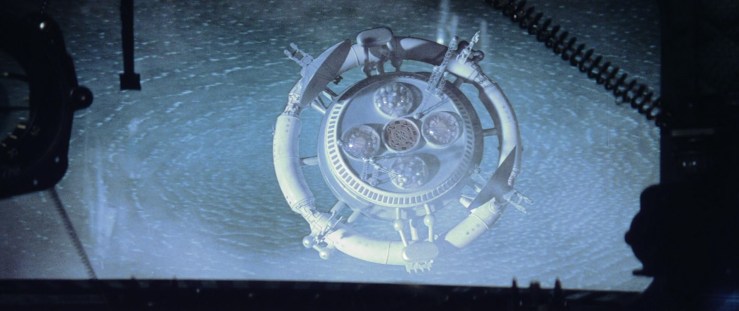

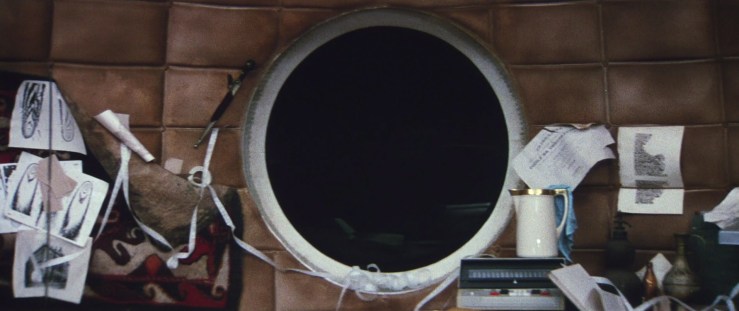

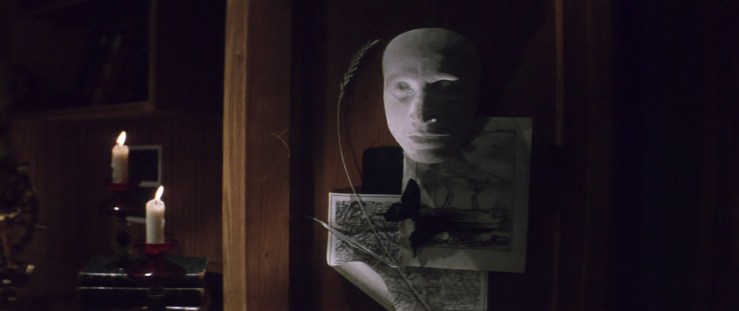

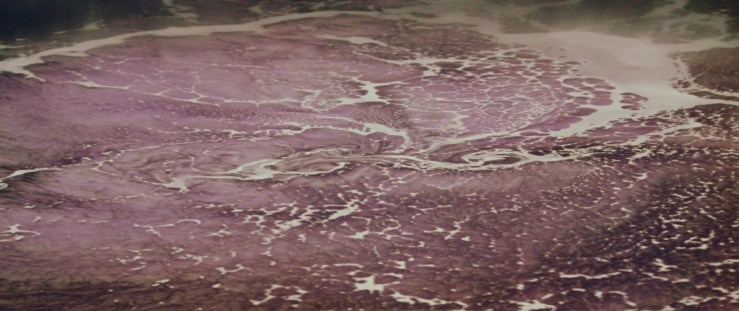

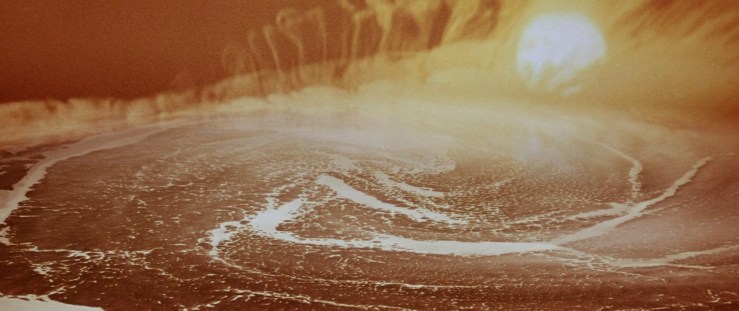

“It’s the story of a spaceship that for a long time has been looking for a planet habitable by the human race. At last they find one, but it’s been many years since they set off on the voyage, and the crew has changed; they’ve all gotten older, but you have to realize that they were very young when they set off. . . . What’s changed are their beliefs: sects, secret societies, covens have sprung up. . . . The ship has also fallen into disrepair—there are computers that don’t work, blown-out lights that no one bothers to fix, wrecked sleeping compartments. . . . Then, when they find the new planet, the mission is completed and they’re supposed to return to Earth with the news, but no one wants to go back. . . . The voyage will consume the rest of their youth, and they’ll return to an unknown world, because meanwhile several centuries have gone by on Earth, since they’ve been traveling at close to light speed. . . . It’s just a starving, overpopulated planet. . . . And there are even those who believe that there is no life left on Earth. . . . Among them is Johann, the protagonist. . . . Johann is a quiet man, one of the few who love the ship. . . . He’s of average height. . . . There’s a hierarchy of height; the woman who’s captain of the ship, for example, is the tallest, and the privates are the shortest. . . . Johann is a lieutenant; he goes about his duties without making too many friends. Like nearly everyone, he’s set in his ways; he’s bored . . . until they reach the strange planet. . . . Then Johann discovers that his shadow has grown darker. . . . Black as outer space and dense . . . As you probably guessed, it’s not his shadow but a separate being that’s taken over there, mimicking the movements of his shadow. . . . Where has it come from? The planet? Space? We’ll never know, and it doesn’t really matter. . . . The Shadow is powerful, as we’ll see, but as silent as Johann. . . . Meanwhile the sects are preparing to mutiny. . . . A group tries to convince Johann to join them; they tell him that he’s one of the chosen, that their common fate is to create something new on this planet. . . . Some seem pretty loony, others dangerous. . . . Johann commits to nothing. . . . Then the Shadow transports him to the planet. . . . It’s a vast jungle, a vast desert, a vast beach. . . . Johann, dressed only in shorts and sandals, almost like a Tyrolean, walks through the undergrowth. . . . He moves his right leg when he feels the Shadow push against his right leg, then the left, slowly, waiting. . . . The darkness is total. . . . But the Shadow looks after him as if he’s a child. . . . When he returns, rebellion breaks out. . . . It’s total chaos. . . . Johann, as a precaution, takes off his officer’s stripes. . . . Suddenly he runs into Helmuth, the captain’s favorite and one of the heads of the rebellion, who tries to kill him, but the Shadow overpowers him, choking him to death. . . . Johann realizes what’s happening and makes his way to the bridge; the captain and some of the other officers are there, and on the screens of the central computer they see Helmuth and the mutineers readying a laser cannon. . . . Johann convinces them that all is lost, that they must flee to the planet. . . . But at the last minute, he stays behind. . . . He returns to the bridge, disconnects the fake video feed that the computer operators have manipulated, and sends an ultimatum to the rebels. . . . Whoever lays down arms this very instant will be pardoned; the rest will die. . . . Johann is well acquainted with the tools of falsehood and propaganda. . . . Then, too, he has the police and the marines on his side, who’ve spent the voyage in hibernation, and he knows that no one can snatch victory from him. . . . He finishes his communiqué with the announcement that he is the new captain. . . . Then he plots another route and abandons the planet. . . . And that’s all. . . . But then I dreamed about Thea von Harbou, and I realized that it was a Millennial Reich ship. . . . They were all Germans . . . all trapped in entropy. . . . Though there are a few weird things, strange things. . . . Under the effects of some drug, one of the girls—the one who sleeps most often with Johann—remembers something painful, and, weeping, she says that her name is Joan. . . . The girl’s real name is Grit, and Johann thinks that maybe her mother called her Joan when she was a baby. . . . Old-fangled and unfashionable names, banned by the psychologists, too . . .”

“Maybe the girl was trying to say that her name was Johann.”

“Possibly. The truth is, Johann is a serious fucking opportunist.”

“So why doesn’t he stay on the planet?”

“I don’t know. Leaving the planet, and not going back to Earth, is like choosing death, isn’t it? Or maybe the Shadow convinced him that he shouldn’t colonize the planet. Either way, the captain and a bunch of people are stuck there. Listen, read the novel, it’s really good. . . . And now I think the swastika came from the dream, not Gene Wolfe. . . . Though who knows . . . ?”

“So you dreamed about Thea von Harbou . . .”

“Yes, it was a blond girl.”

“But have you ever seen a picture of her?”

“No.”

“How did you know it was Thea von Harbou?”

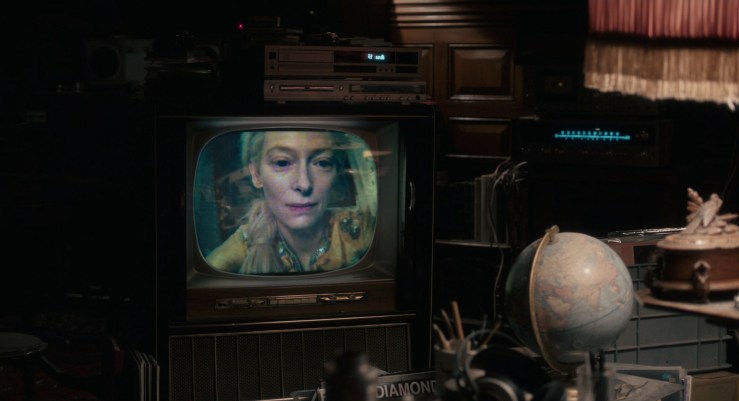

“I don’t know, I guessed it. She was like Marlene Dietrich singing ‘Blowin’ in the Wind,’ the Dylan song, you know? Weird stuff, spooky, but very up-close and personal—it’s hard to explain, but personal.”

“So the Nazis take over the Earth and send ships in search of new worlds.”

“Yes. In Thea von Harbou’s version.”

“And they find the Shadow. Isn’t that a German story?”

“The story of the Shadow or the man who loses his shadow? I don’t know.”

“And it was Thea von Harbou who told yo all this?”

“Johann believes that inhabited planets, or habitable planets, are the exception in the universe. . . . As he tells it, Guderian’s tanks lay waste to Moscow . . .”

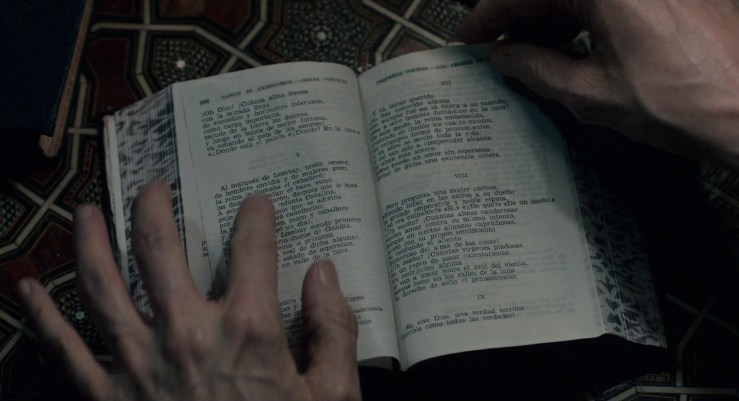

From Roberto Bolaño’s novel The Spirit of Science Fiction. English translation by Natasha Wimmer.

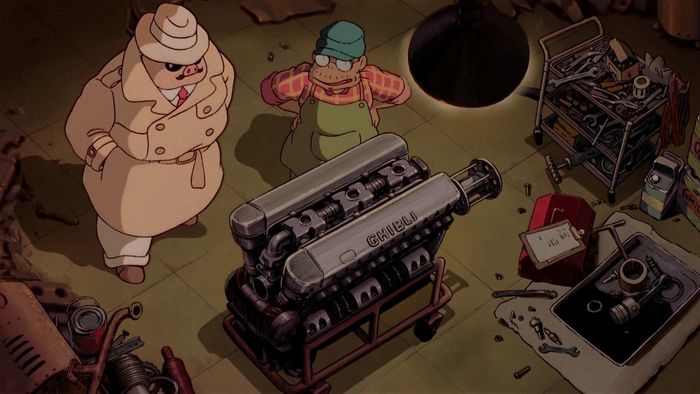

Gene Wolfe’s 1975 novella Silhouette was originally published in The New Atlantis, an anthology of sci-fi edited by Robert Silverberg, and later collected in Endangered Species (1989). Silhouette begins with an epigraph culled from Ambrose Bierce’s short story “A Psychological Shipwreck” (1879):

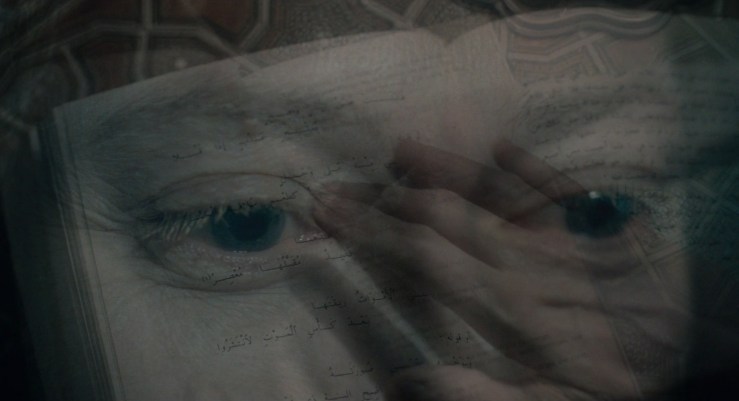

To sundry it is given to be drawn away, and to be apart from the body for a season; for, as concerning rills which would flow across each other the weaker is borne along by the stronger, so there be certain of kin whose paths intersecting, their souls do bear company, the while their bodies go foreappointed ways, unknowing.

In Bierce’s story, this passage is itself quoted from “that rare and curious work, Denneker’s Meditations.”

Thea von Harbou wrote many novels and screenplays, including numerous screenplays for her husband director Fritz Lang, including the classic sci-fi film Metropolis. After its ascendance to power, von Harbou remained loyal to the Nazi party.