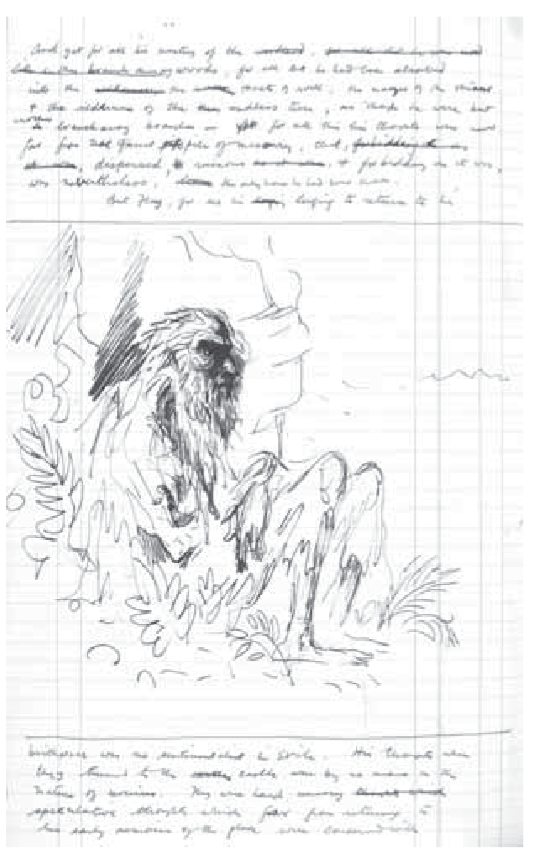

Illustration for Elena Poniatowska’s children’s novel, Lilus Kikus, c. 1954 by Leonora Carrington (1917 – 2011)

Illustration for Elena Poniatowska’s children’s novel, Lilus Kikus, c. 1954 by Leonora Carrington (1917 – 2011)

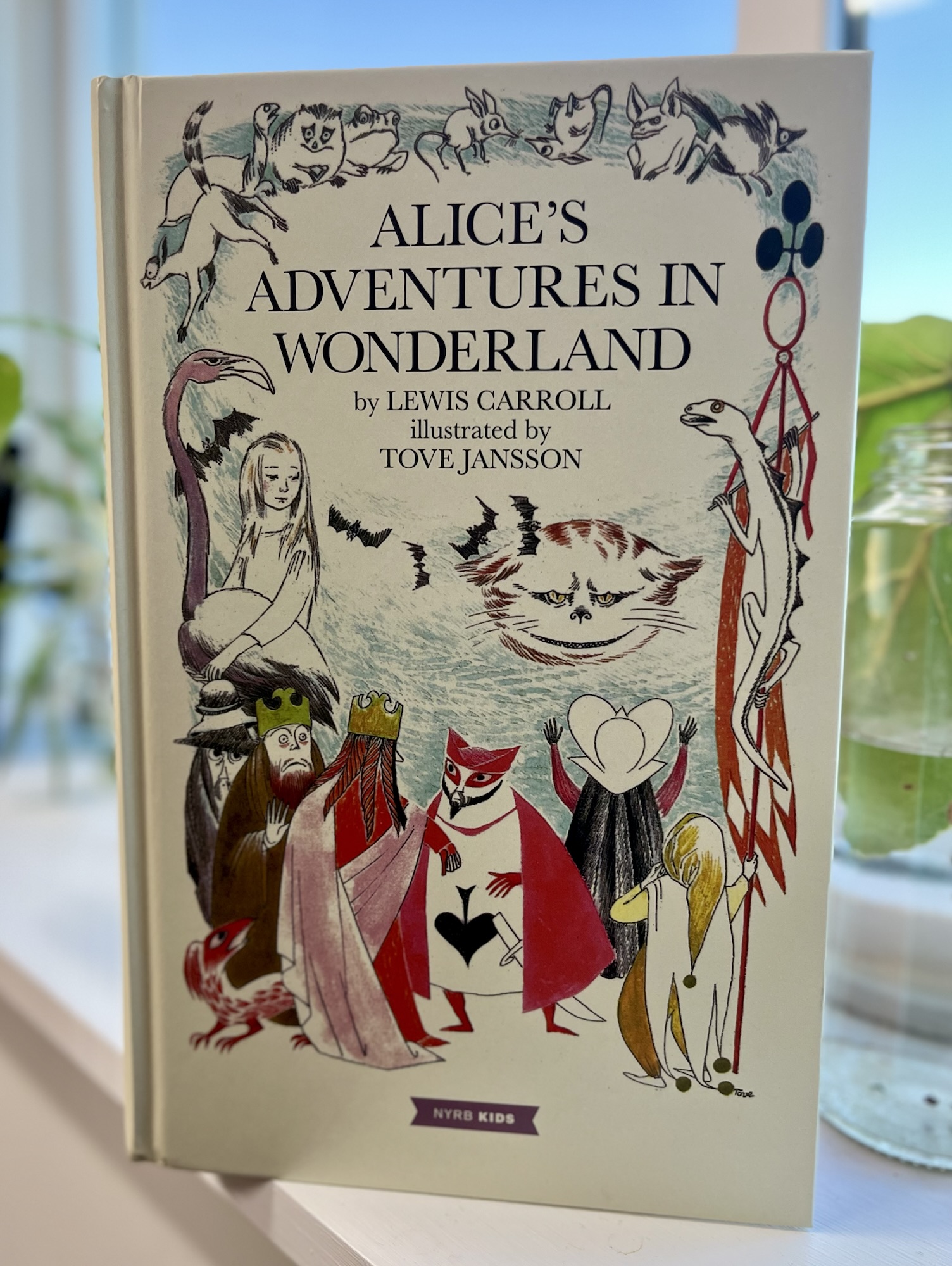

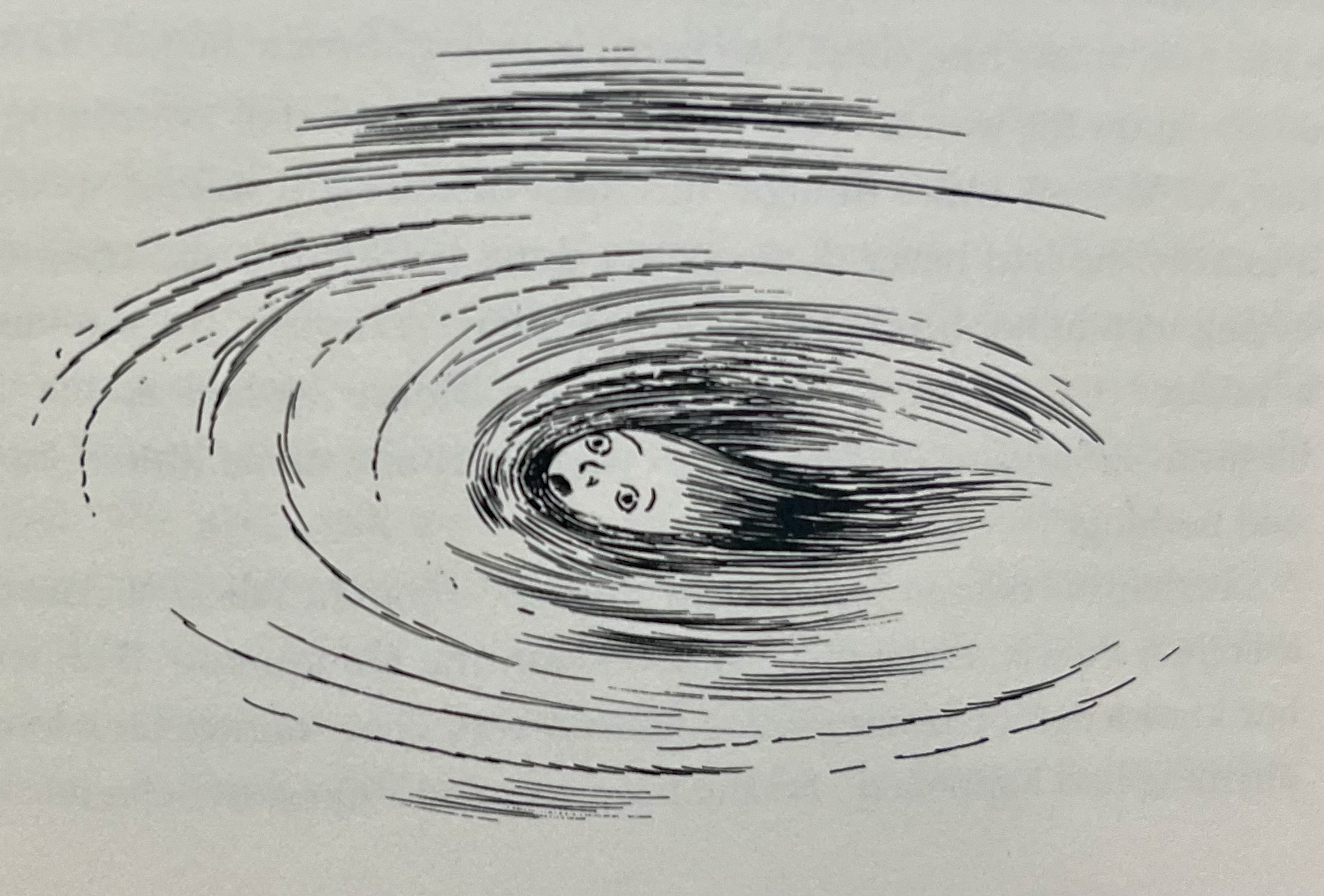

This fall–just in time for the holiday season–the NYRB Kids imprint has published an edition of Lewis Carroll’s classic Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland illustrated by the Finnish author and artist Tove Jansson. Jansson is most famous for her Moomin books, which remain an influential cult favorite with kids and adults alike. She illustrated Carroll’s Alice in 1966 for a Finnish audience; this NRYB edition is the first English-language version of the book. There are illustrations on almost every page of the book; most are black and white sketches — doodles, portraits, marginalia — but there are also many full-color full-pagers, like this odd image about a dozen pages in:

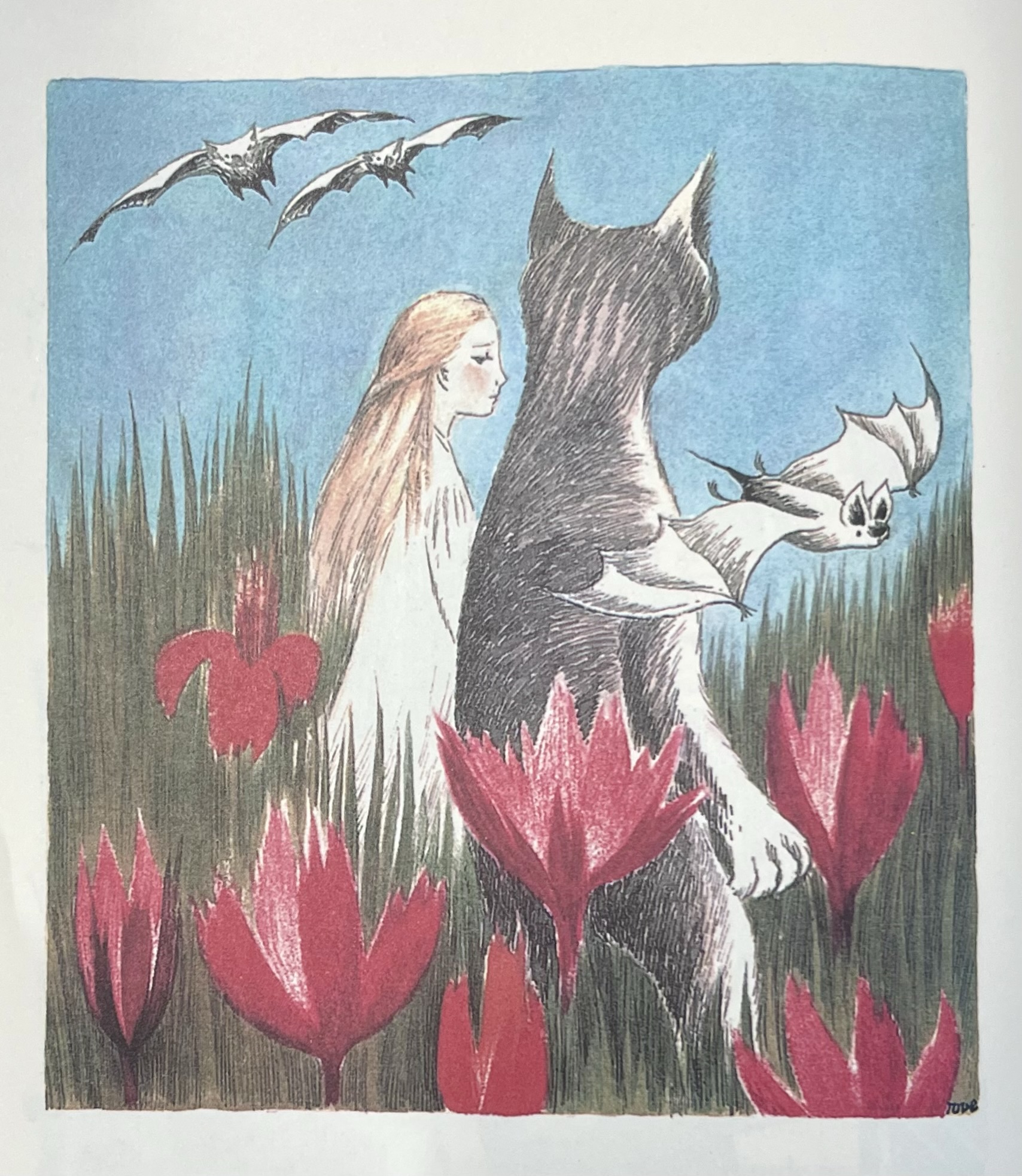

Here we have Alice and her cat Dinah, transformed into a shadowy, even sinister figure, large, bipedal. Bats float in the background, echoing Goya’s famous print El sueño de la razón produce monstruos. The image accompanies Alice’s initial descent into her underland wonderland: “Down, down, down. There was nothing else to do, so Alice soon began talking again,” addressing Dinah, who will “miss me very much to-night, I should think!” Wonderlanding if Dinah might catch a bat, which is something like a mouse, maybe, “Alice began to get rather sleepy, and went on saying to herself, in a dreamy sort of way, ‘Do cats eat bats? Do cats eat bats?’ and sometimes, ‘Do bats eat cats?; for, you see, as she couldn’t answer either question, it didn’t much matter which way she put it.” Jansson’s red flowers suggest poppies, contributing to the scene’s slightly-menacing yet dreamlike vibe. The image ultimately echoes the myth of Hades and Persephone.

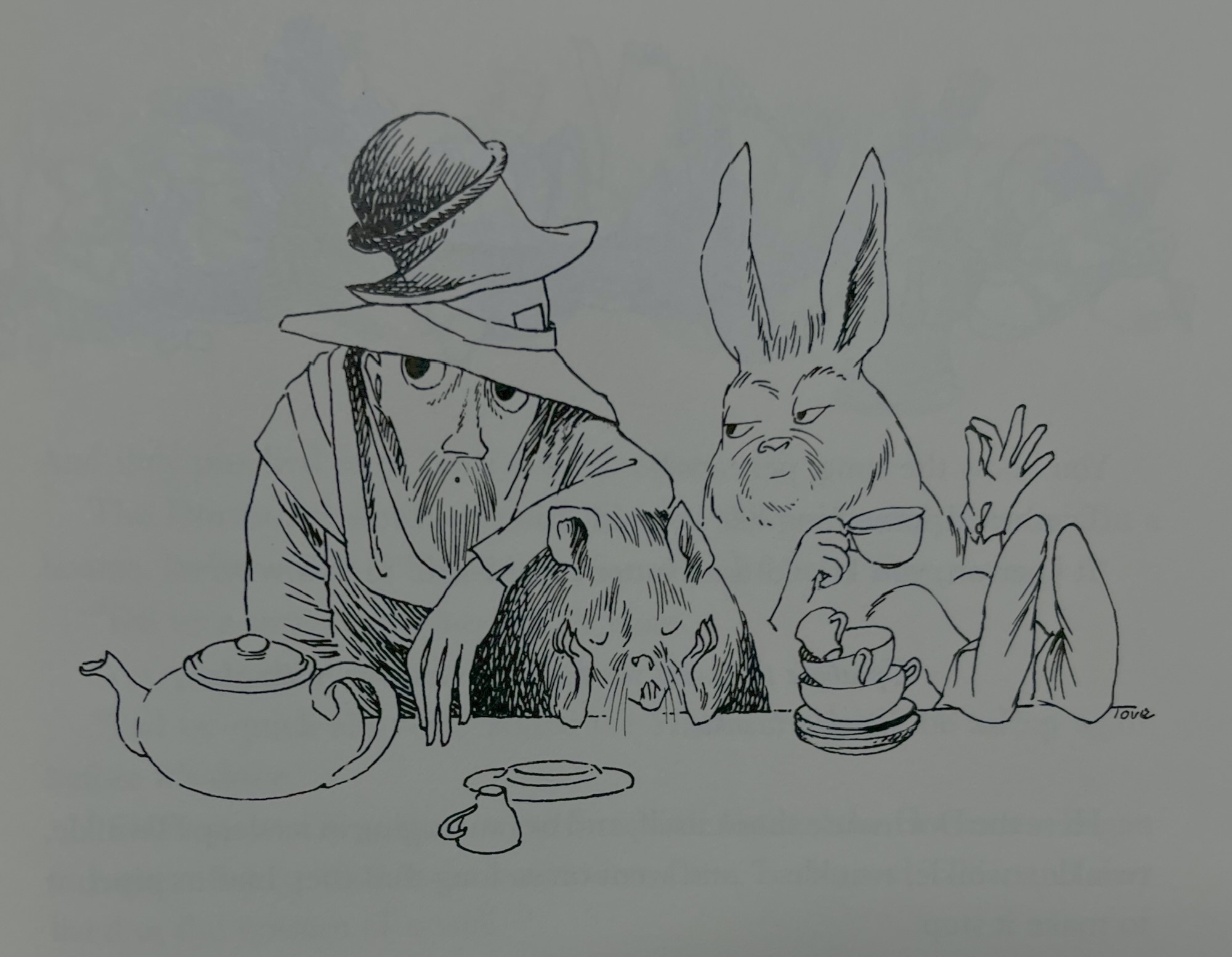

All the classic characters are here, of course, rendered in Jansson’s sensitive ink. Consider this infamous trio —

There was a table set out under a tree in front of the house, and the March Hare and the Hatter were having tea at it: a Dormouse was sitting between them, fast asleep, and the other two were using it as a cushion, resting their elbows on it, and talking over its head.

I love Jansson’s take on the Hatter; he’s not the outright clown we often see in post-Disneyfied takes on the character, but rather a creature rendered in subtle pathos. The March Hare is smug; the Dormouse is miserable.

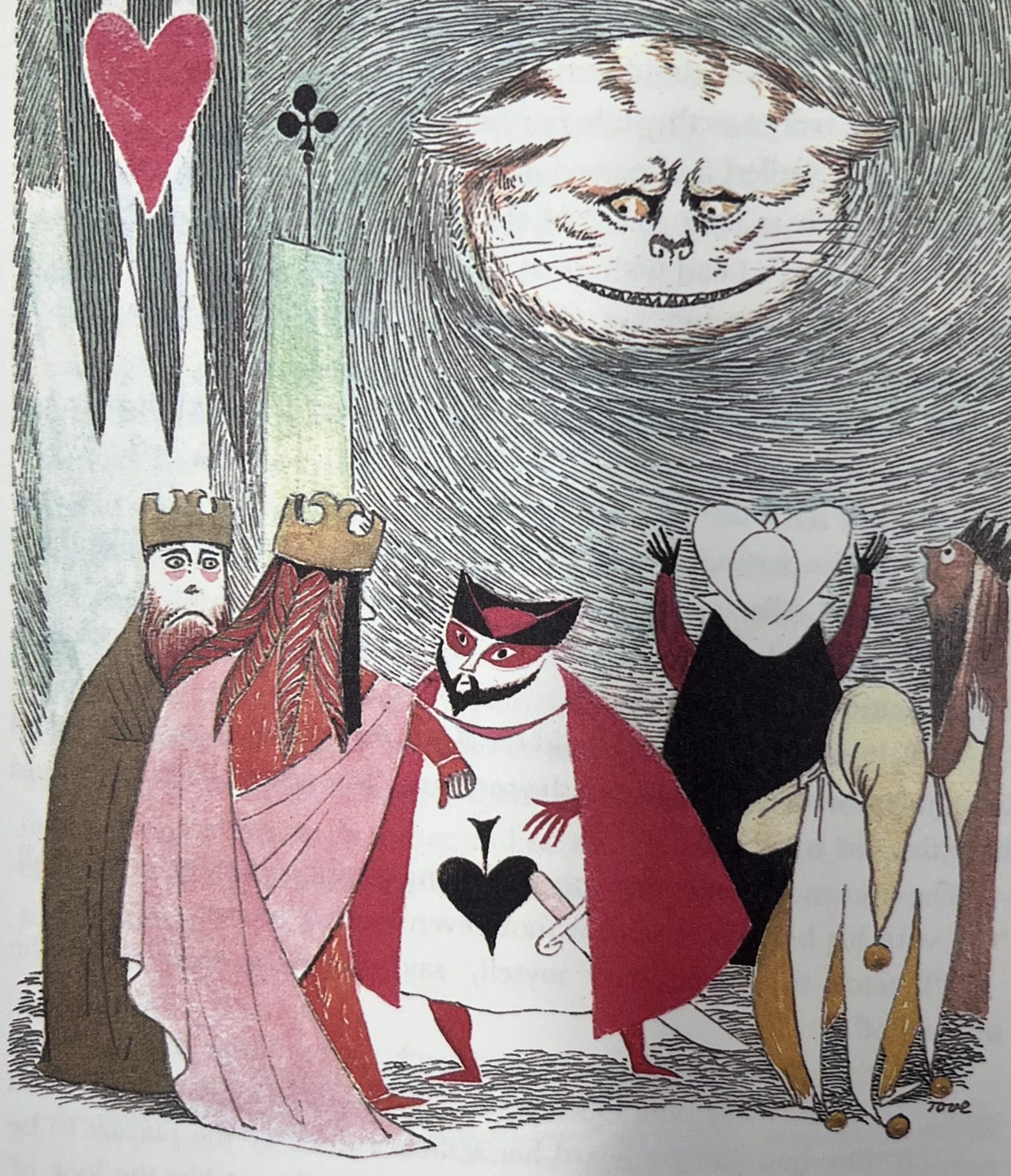

And you’ll want a glimpse of the famous Cheshire cat who appears (and disappears) during the Queen’s croquet match:

Jansson’s figures here remind one of the surrealist Remedios Varo’s strange, even ominous characters. Like Varo and fellow surrealist Leonora Carrington, Jansson’s art treads a thin line between whimsical and sinister — a perfect reflection of Carroll’s Alice, which we might remember fondly as a story of magical adventures, when really it is much closer to a horror story, a tale of being sucked into an underworld devoid of reason and logic, ruled by menacing, capricious, and ultimately invisible forces. It is, in short, a true reflection of childhood,m. Great stuff.

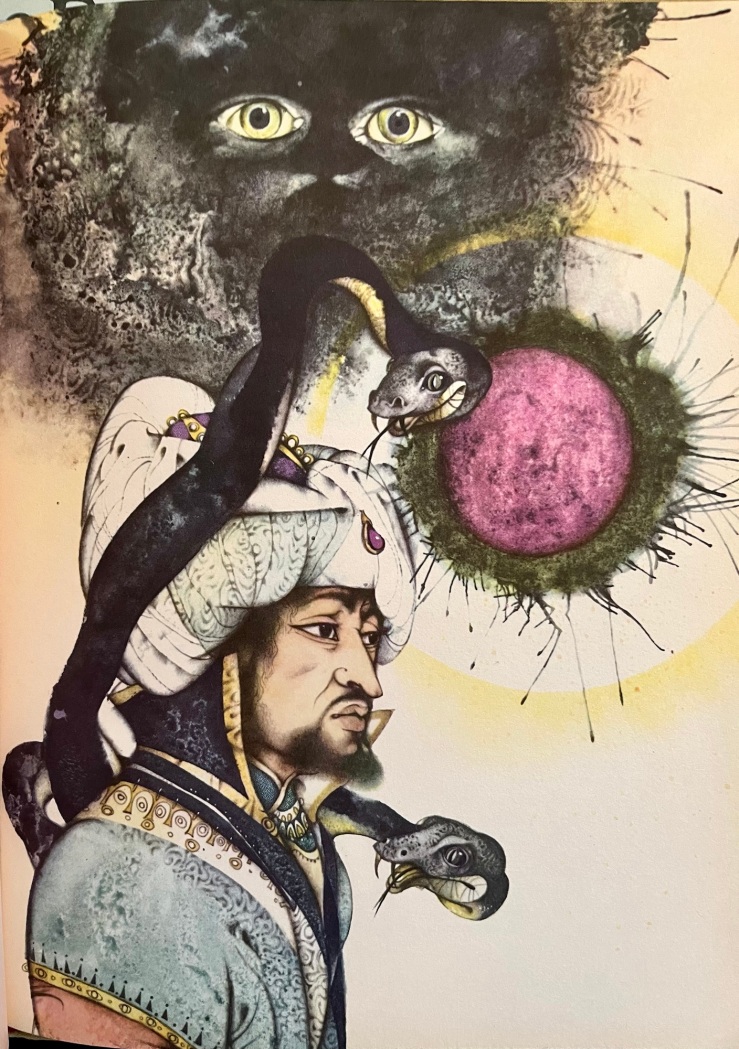

Luděk Maňásek’s illustration for “The Snake King.” From Jaroslav Tichý’s Persian Fairy Tales, Hamlyn, 1970. (English translations in the collection are by Jane Carruth).

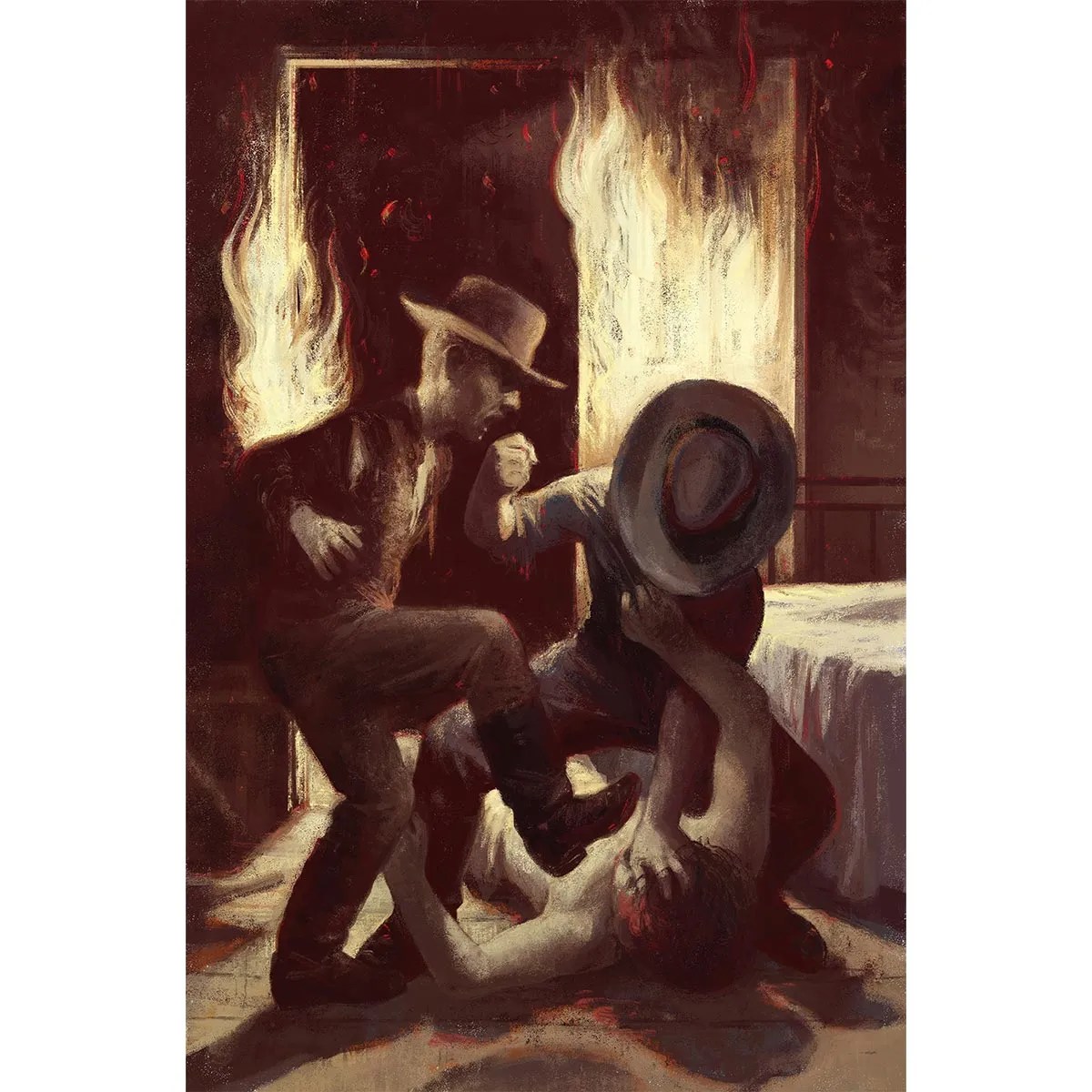

Illustration for Cormac McCarthy’s novel Blood Meridian by Gérard DuBois. From the Folio Society edition of Blood Meridian.

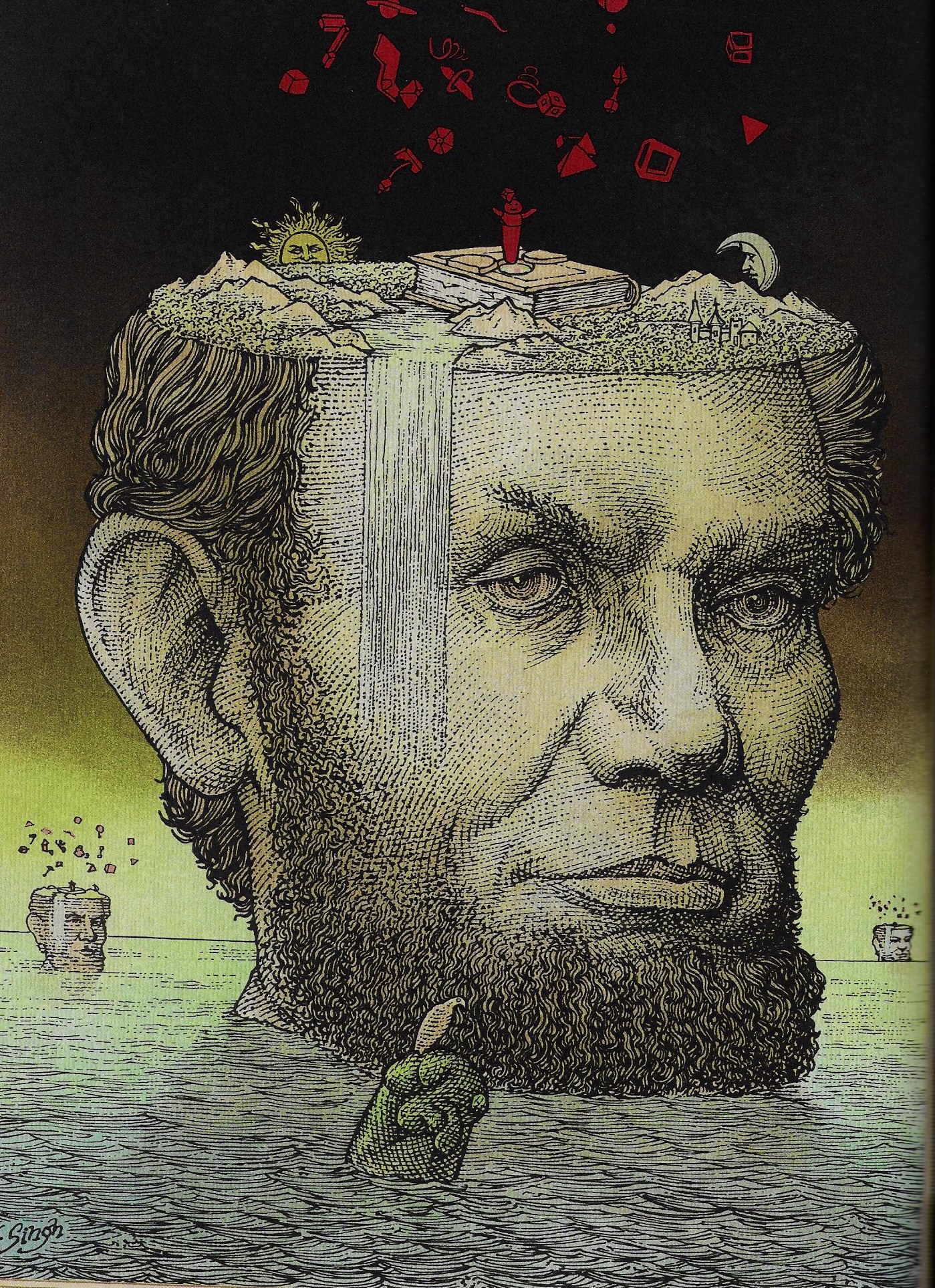

A portrait of Abraham Lincoln, from Adventure Time: The Enchiridion & Marcy’s Super Secret Scrapbook, 2015, by Mahendra Singh (b. 1961)

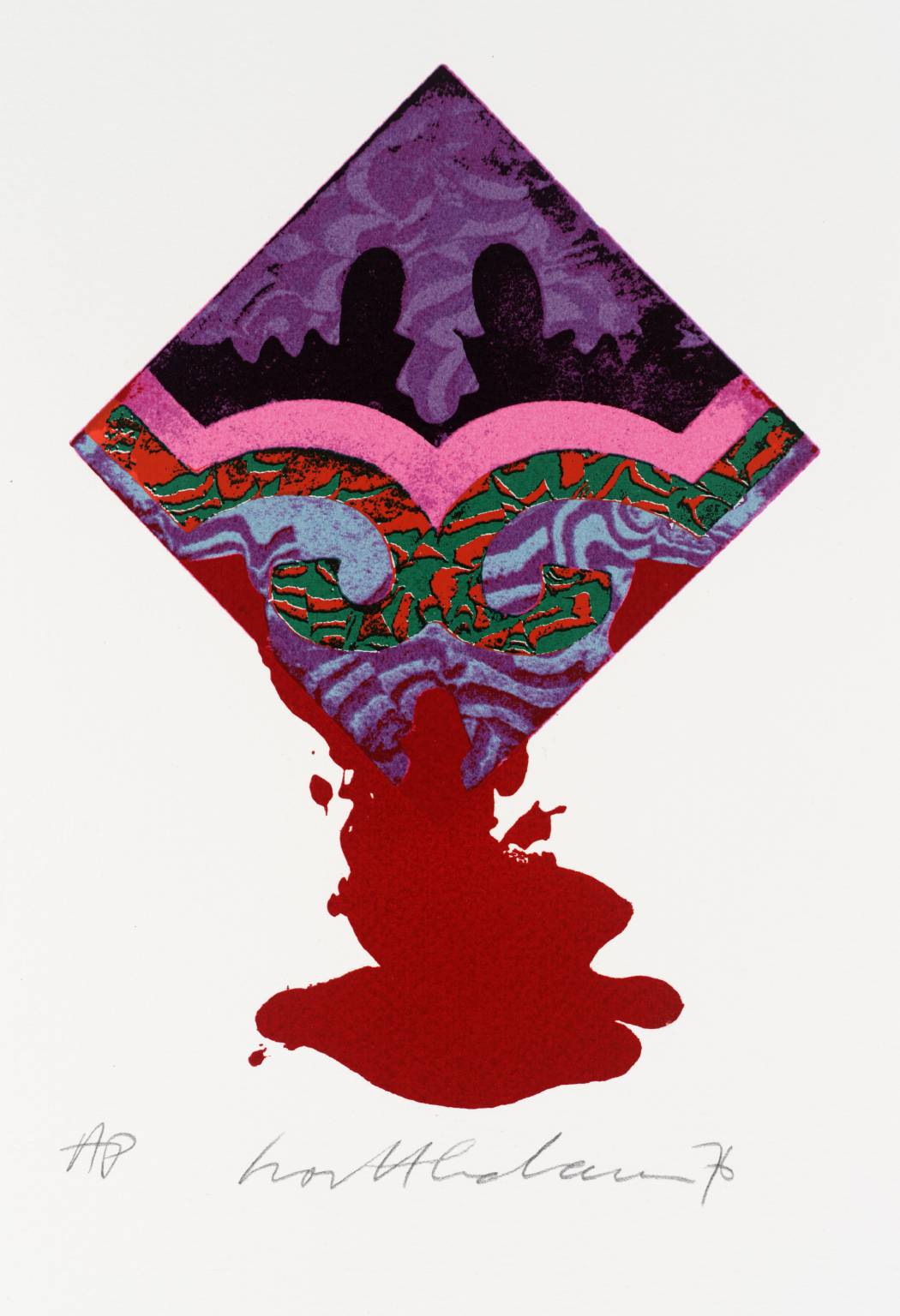

Illustration for Poe’s “The Masque of Red Death,” 1976 by Ivor Abrahams (1935–2015)

“The Masque of Red Death”

by

Edgar Allan Poe

The “Red Death” had long devastated the country. No pestilence had ever been so fatal, or so hideous. Blood was its Avatar and its seal—the redness and the horror of blood. There were sharp pains, and sudden dizziness, and then profuse bleeding at the pores, with dissolution. The scarlet stains upon the body and especially upon the face of the victim, were the pest ban which shut him out from the aid and from the sympathy of his fellow-men. And the whole seizure, progress and termination of the disease, were the incidents of half an hour.

But the Prince Prospero was happy and dauntless and sagacious. When his dominions were half depopulated, he summoned to his presence a thousand hale and light-hearted friends from among the knights and dames of his court, and with these retired to the deep seclusion of one of his castellated abbeys. This was an extensive and magnificent structure, the creation of the prince’s own eccentric yet august taste. A strong and lofty wall girdled it in. This wall had gates of iron. The courtiers, having entered, brought furnaces and massy hammers and welded the bolts. They resolved to leave means neither of ingress nor egress to the sudden impulses of despair or of frenzy from within. The abbey was amply provisioned. With such precautions the courtiers might bid defiance to contagion. The external world could take care of itself. In the meantime it was folly to grieve, or to think. The prince had provided all the appliances of pleasure. There were buffoons, there were improvisatori, there were ballet-dancers, there were musicians, there was Beauty, there was wine. All these and security were within. Without was the “Red Death”.

It was towards the close of the fifth or sixth month of his seclusion, and while the pestilence raged most furiously abroad, that the Prince Prospero entertained his thousand friends at a masked ball of the most unusual magnificence. Continue reading “Illustration for Poe’s “The Masque of Red Death” — Ivor Abrahams”

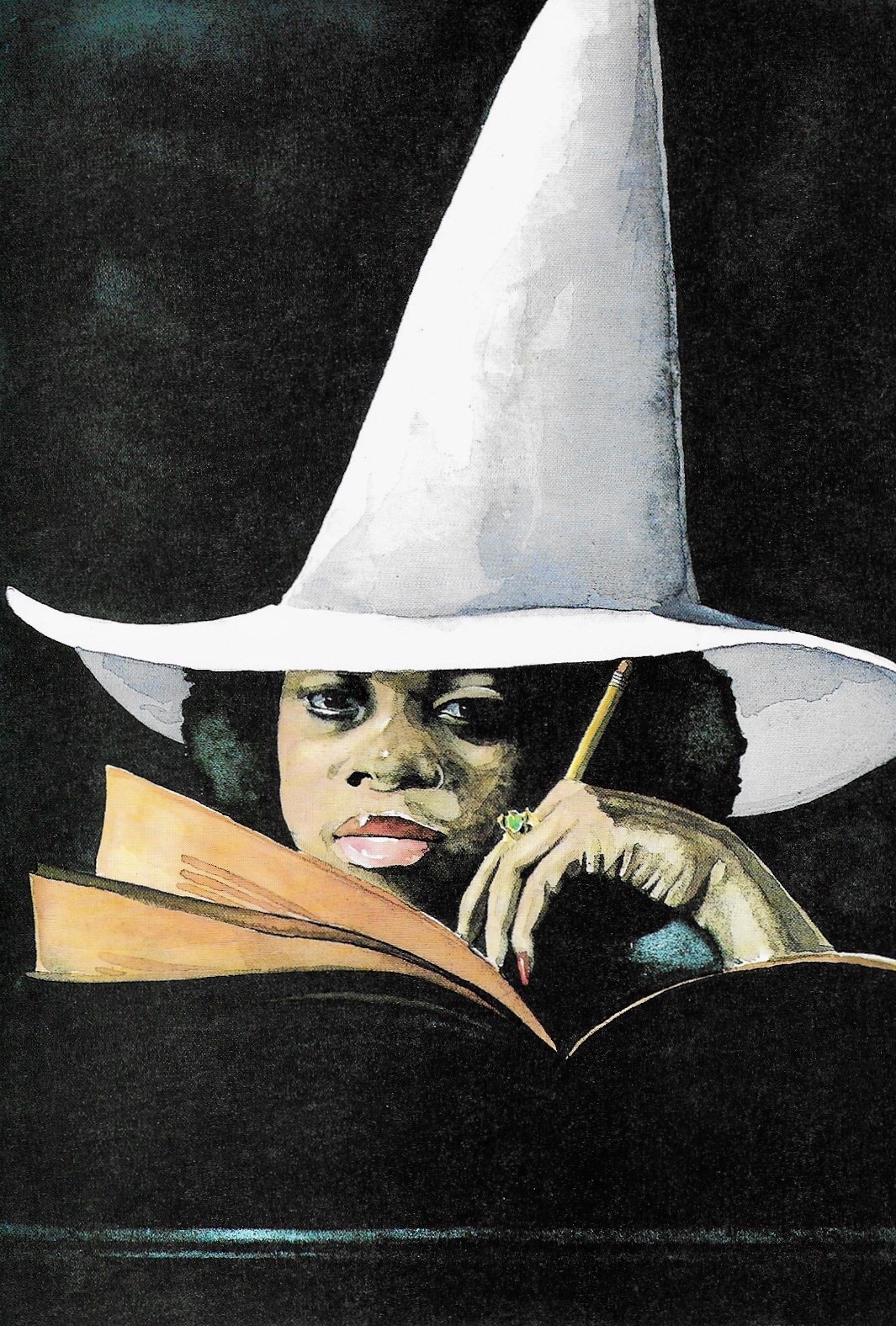

Barry Moser’s illustration for Lynne Reid Banks’s “The Hare and the Black-and-White Witch.” From The Magic Hare, Avon, 1994.

![Canto X: [no title] 1982 by Tom Phillips born 1937](https://biblioklept.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/p07693_10.jpg)

Canto X, 1982 by Tom Phillips (b. 1937). From the Dante’s Inferno series.

Thomas Pynchon’s short story “The Secret Integration” was first published in a December issue of The Saturday Evening Post, and later published again as part of Pynchon’s first and only short story collection, Slow Learner.

In a 2018 article published at The Yale Review, Terry Reilly suggested that by publishing “The Secret Integration” in The Saturday Evening Post,

…Pynchon uses the form of an apparently simple, entertaining adolescent boys’ story to engage and then to manipulate the Post readers; to invoke various features of the publication history of The Saturday Evening Post while simultaneously calling attention to the magazine’s limited scope and conservative bias concerning issues of civil rights and racial integration in 1964.

Pynchon’s story was accompanied by three illustrations by the cartoonist Arnold Roth, including a header, a small illustration, and this full page illustration below:

The first page of the story:

by

Thomas Pynchon

OUTSIDE it was raining, the first rain of October, end of haying season and of the fall’s brilliance, purity of light, a certain soundness to weather that had brought New Yorkers flooding up through the Berkshires not too many weekends ago to see the trees changing in that sun. Today, by contrast, it was Saturday and raining, a lousy combination. Inside at the moment was Tim Santora, waiting for ten o’clock and wondering how he was going to get out past his mother. Grover wanted to see him at ten this morning, so he had to go. He sat curled in an old washing machine that lay on its side in a back room of the house; he listened to rain going down a drainpipe and looked at a wart that was on his finger. The wart had been there for two weeks and wasn’t going to go away. The other day his mother had taken him over to Doctor Slothrop, who painted some red stuff on it, turned out the lights and said, “Now, when I switch on my magic purple lamp, watch what happens to the wart.” It wasn’t a very magic-looking lamp, but when the doctor turned it on, the wart glowed a bright green. “Ah, good,” said Doctor Slothrop. “Green. That means the wart will go away, Tim. It hasn’t got a chance.” But as they were going out, the doctor said to Tim’s mother, in a lowered voice Tim had learned how to listen in on, “Suggestion therapy works about half the time. If this doesn’t clear up now spontaneously, bring him back and we’ll try liquid nitrogen.” Soon as he got home, Tim ran over to ask Grover what “suggestion therapy” meant. He found him down in the cellar, working on another invention. Continue reading “Arnold Roth’s original illustrations for Thomas Pynchon’s 1964 short story “The Secret Integration” (and a link to the full text of the story)”

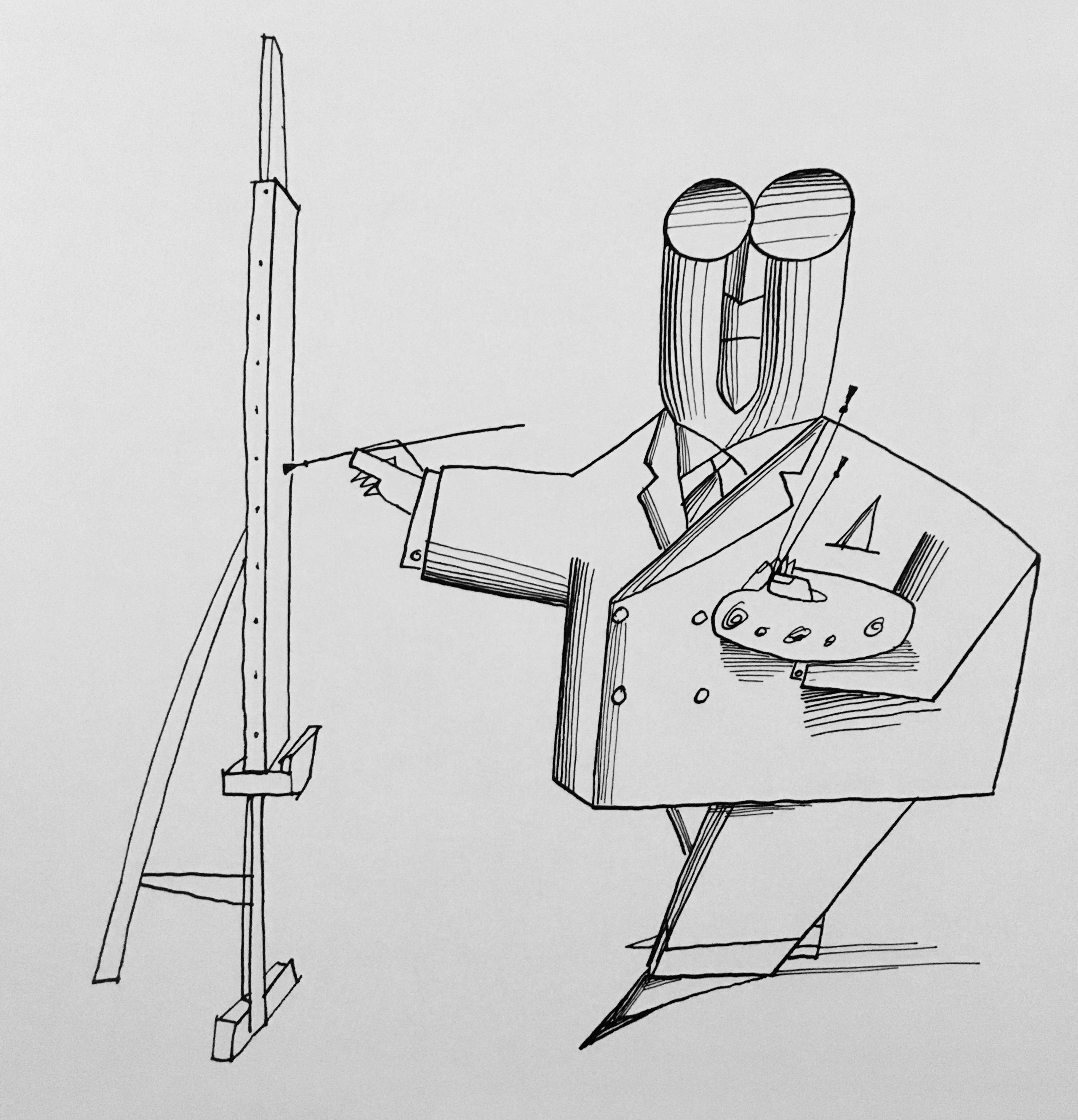

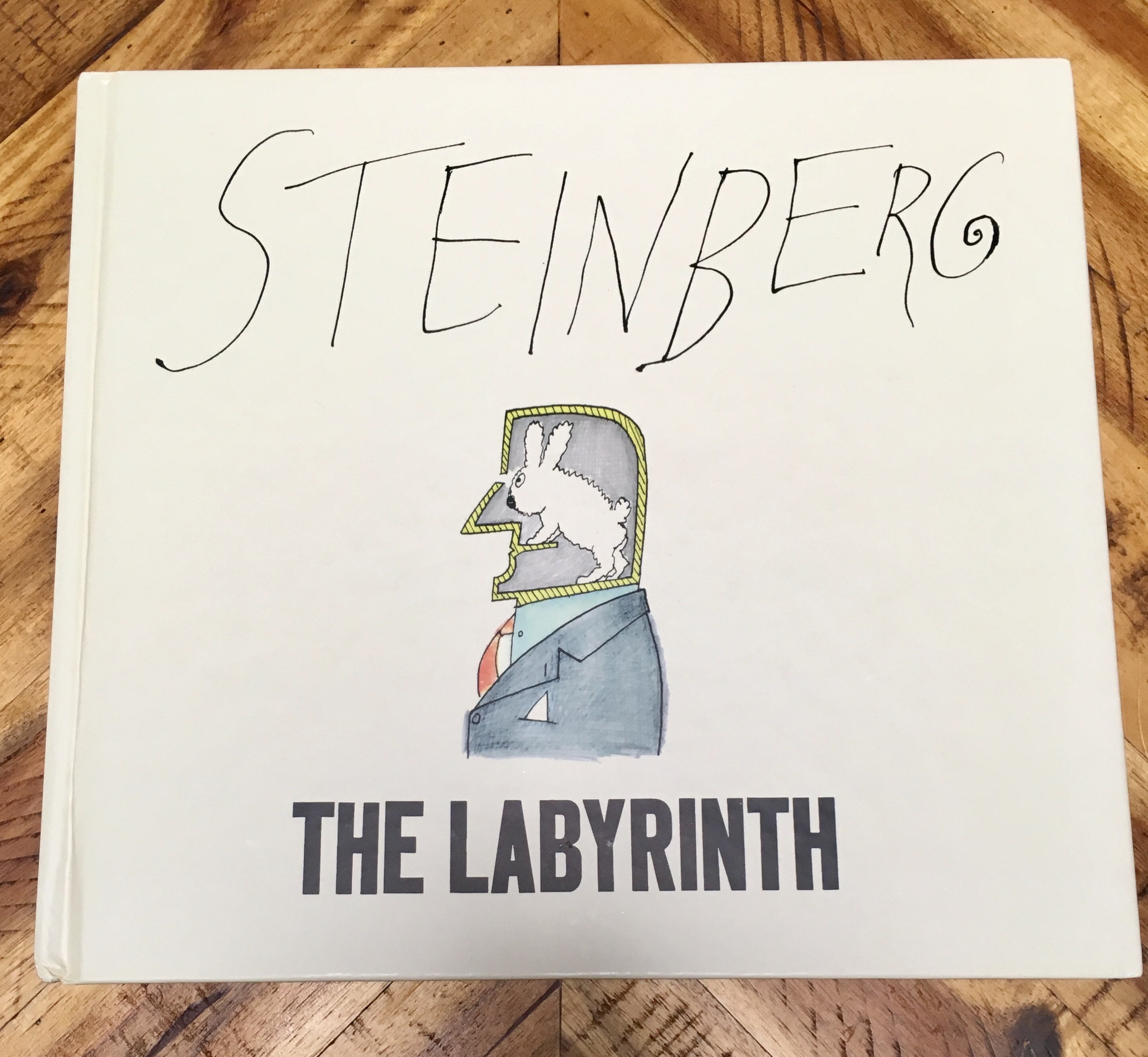

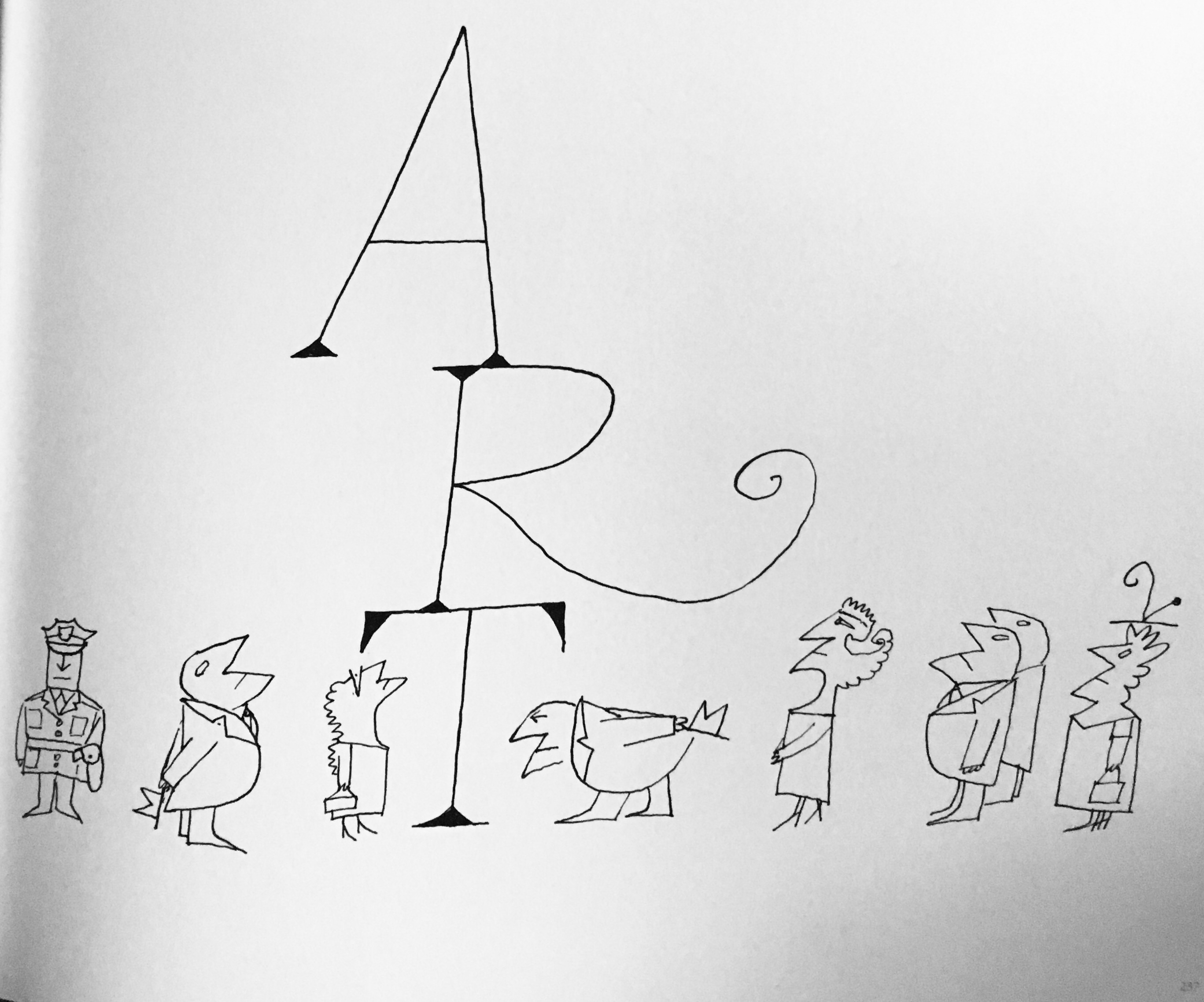

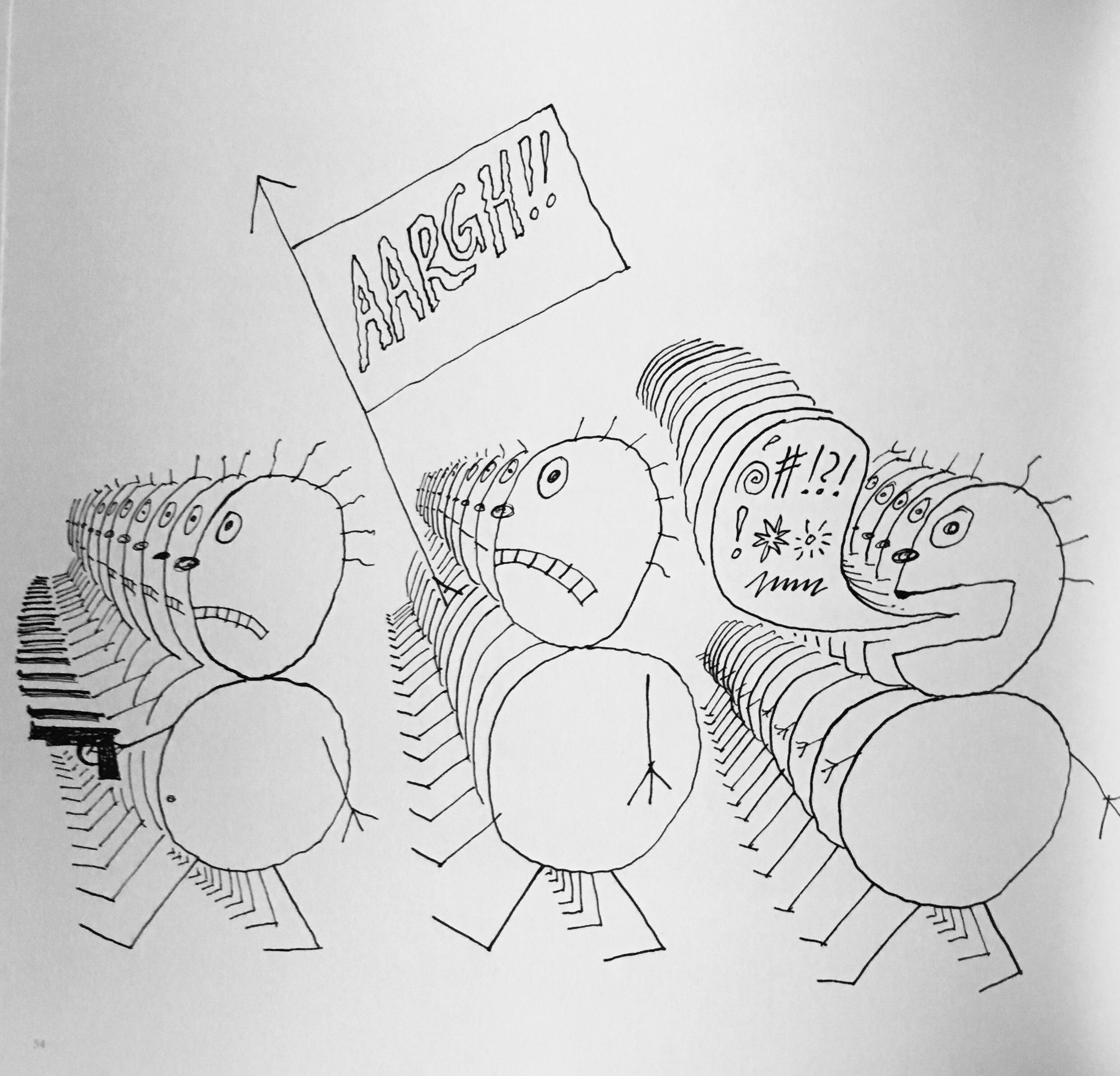

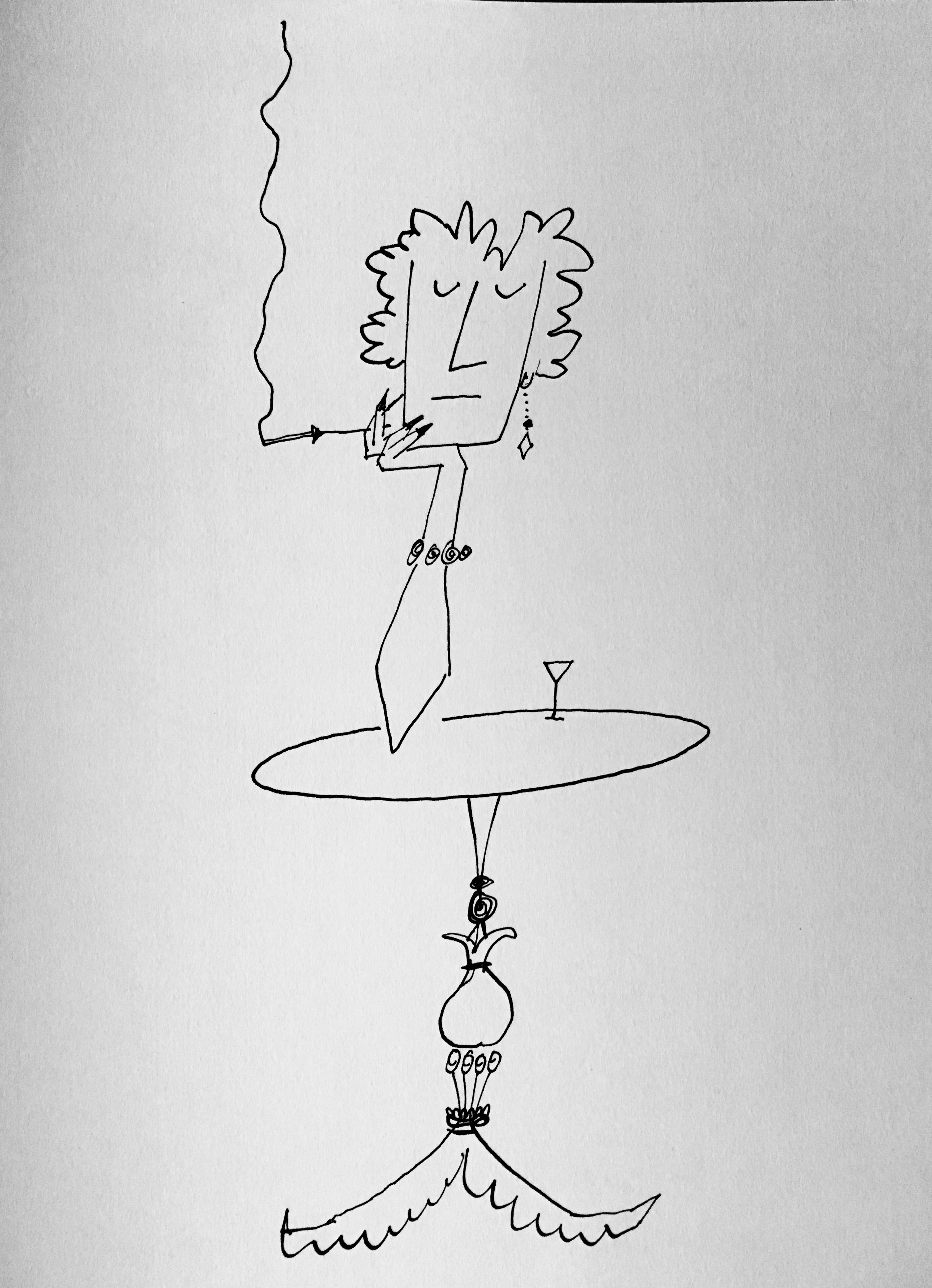

Saul Steinberg’s The Labyrinth is new in print again from NYRB, this time with a new introduction by novelist Nicholson Baker. The book is simply gorgeous.

My eight-year-old son immediately asked if he might read it (he has been on a sort of comix probation since I caught him reading a R. Crumb collection), and he shuttled through the thing two or three times over half an hour.

The Labryinth is 280 or so pages of illustrations with no story or plot, and he was a bit bewildered when I told him I planned to review the thing. “How?” I’ll figure out a way.

For now, here’s NYRB’s blurb:

Saul Steinberg’s The Labyrinth, first published in 1960 and long out of print, is more than a simple catalog or collection of drawings— these carefully arranged pages record a brilliant, constantly evolving imagination confronting modern life. Here is Steinberg, as he put it at the time, “discovering and inventing a great variety of events: Illusion, talks, music, women, cats, dogs, birds, the cube, the crocodile, the museum, Moscow and Samarkand (winter, 1956), other Eastern countries, America, motels, baseball, horse racing, bullfights, art, frozen music, words, geometry, heroes, harpies, etc.” This edition, featuring a new introduction by Nicholson Baker, an afterword by Harold Rosenberg, and new notes on the artwork, will allow readers to discover this unique and wondrous book all over again.

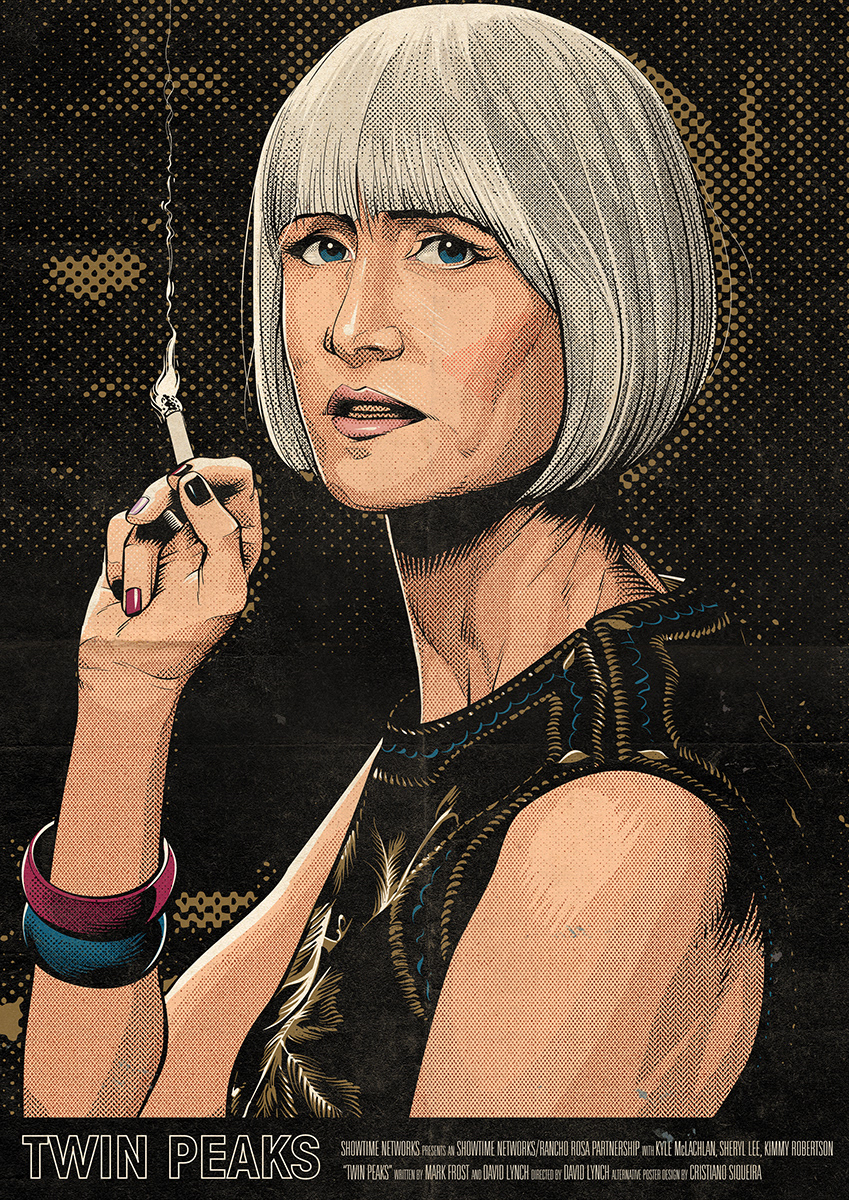

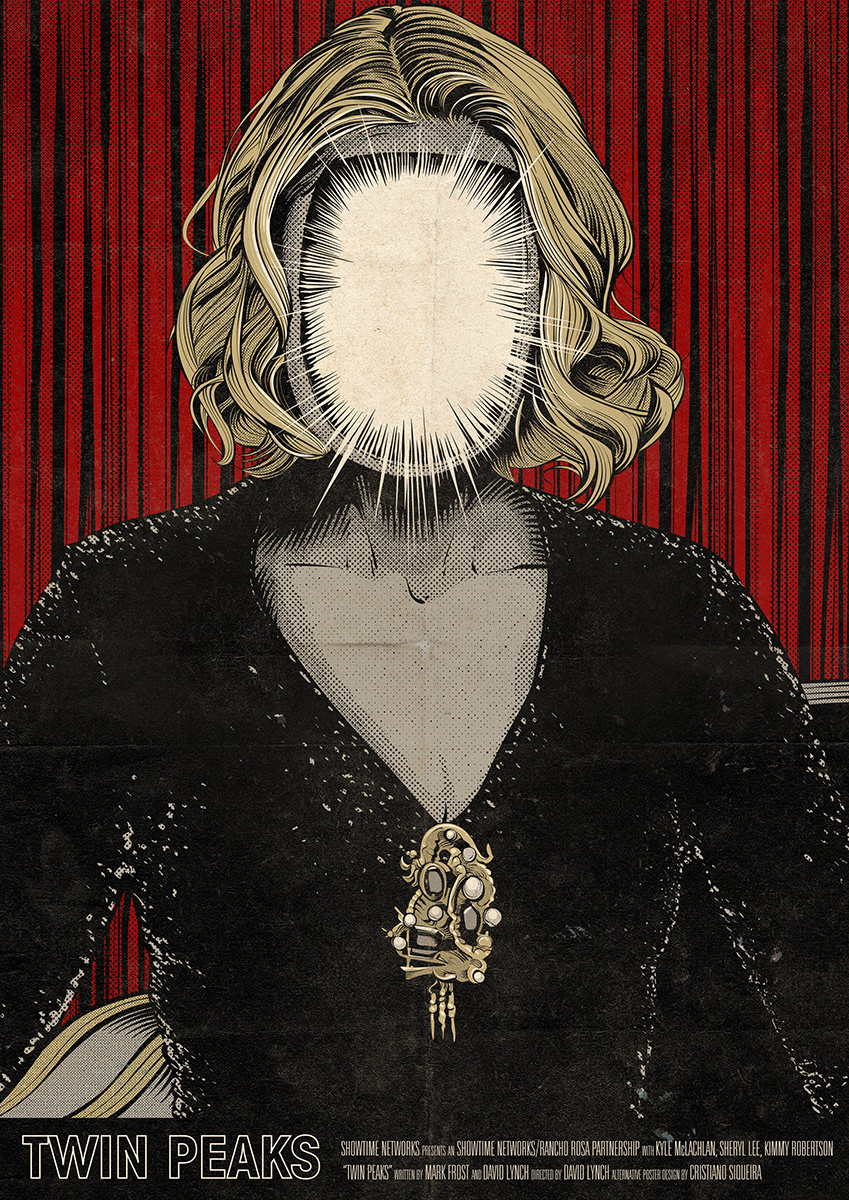

I somehow missed Cristiano Siqueira’s series of posters for Twin Peaks: The Return. Siqueira did a poster for each episode of David Lynch’s 2017 sequel—19 posters in all, including a bonus poster depicting Audrey. Check out all nineteen posters here.

Cursed Forest by Kilian Eng (b. 1982)