New Zealand writer Carl Shuker is the author of four novels, including Three Novellas for a Novel, cult novel The Lazy Boys, and The Method Actors. His latest novel is Anti Lebanon (Counterpoint Press) is a strange work of surreal horror, set primary in Lebanon in the immediate fallout of the Arab Spring. In my review, I wrote that Anti Lebanon’s “trajectory repeatedly escapes the reader’s expectations, driving into increasingly alien terrain.”

Carl was kind enough to talk about his work over a series of emails. He was especially kind in letting Biblioklept publish the short story “Fiction” which he mentions in the first part of this interview.

Biblioklept: How did Anti Lebanon begin? Did you set out to write about a Lebanese Christian? Tell us about the genesis of the novel and your research process.

Carl Shuker: Anti Lebanon started with the words, and the disjunction between my sense memories of the words, the place names and the language, and the atrocity exhibition of the Lebanese civil war of ‘75-’90 (which we are reliving now in the Syrian civil war).

I was brought up moderately conservative Anglican, which early on involved a lot of Bible stories and Sunday school. I had a very deep and powerful connection with the vocabulary. I remember tasting the words in a totally engrossing synesthesia: lying in bed in a small town in the South Island of New Zealand, ten years old and waiting for sleep and saying the words to myself.

Lebanon, for example, was thick milk and Alpine honey (as Nabokov once described his life). You can taste it in those pregnant Bs, those labile Ls and sonorous Os and Ns. And Syria and Damascus—with the latter I had generated some fertile misprision, I think, because into it I had somehow conflated “alabaster.” So the city had the word within it, and these cool and chalky white walls I felt up under my fingernails were as real to me as the blanket at my cheek. Jounieh, Jtaoui, and Bsharre; Ehden, and Zghorta.

Sometime in late 2006 I lost my agent (of only two years), via a one-paragraph email entitled, chillingly, “Cutting back.” He was a bit older and I hadn’t made him any money so it was understandable.

I saw, after eight years of trying to get it published, that although it did well critically and got a very cult following of some very cool and interesting people (a lot of eastern European teenage girls, pleasingly), that The Lazy Boys (2006) was not going to be any kind of breakthrough. There would be no musical. That book does sometimes feel to me like a cursed chalice. Another two years of querying agents for my Three Novellas for a Novel project had not gotten me representation again. I had no publisher for it. A long-gestating film project with a director and producer finally fell through due to funding and all the difficulties surrounding that. (The screenplay for The Lazy Boys is sitting humming in my drawer.) I was running out of money I had from a prize and I felt after nearly ten years of work I was back almost at square one. Currently I have no agent and I think I’m fortunate to have gotten through the current convulsions in publishing under my own steam. I don’t know what I’d advise a young writer right now, about getting represented.

With writing and publishing, which is a tough and demanding ambient, the cliché is very useful: you get bitter or you get better. Working on a new thing is the best and only antidote to publishing an old thing. It’s always and only the writing that saves you. I started looking around for a new project. Though I don’t write short stories I wrote a suicide note for the lit-fict writer of the time and of the writer I’d almost become, a short story called “Fiction” that started to encompass elements of this new obsession with Lebanon, and to extend it to the consequences of that obsession.

I’m intuitive and a weird hybrid of deeply elemental and playful and airy fairy when I look around for a new project. But I’ve learned to identify and focus in on my obsessions, which is an important skill for a novelist. And usually it is what is troubling me; what I can’t figure out.

Etienne Sakr, a Christian militia leader in the civil war, who has been subsequently exiled and tarred as a rightist and racist and has not emerged from the post-war period at all well, wrote, “Politics is not the art of the possible. Politics, like all great art forms, is the art of the impossible. Otherwise there is no problem to resolve.”

Like all great art forms. This was a conception of the novel as well. The writing is a resolving of unresolved and seemingly irresolvable elements—it’s a tension, also, that can sustain you through the long period of composing something as big and demanding as a novel. Solving some problem you couldn’t any other way.

And the solution was the mode I think I am refining, that I work in by default anyhow. Freud in The Interpretation of Dreams: “Contradictory thoughts do not try to eliminate one another, but continue side by side, and often combine to form condensation products, as though no contradiction existed.”

In Anti Lebanon it was: how to resolve and express this deep but wordless feeling I have for the words of this country, the bloody holy dirt of this country, and the tropes and gestures of the vampire, the monster?

I prepped and read as much as I could on the civil war, and went to Beirut in May 2008 to taste the dirt. This was the same month I published the Three Novellas in serial online for a limited time for free or more, a la Radiohead’s In Rainbows, clearing the decks for something new (These were rereleased with a new introduction, for all ebook formats, in 2011: http://www.threenovellasforanovel.com).

And while I was there Hezbollah invaded Beirut, and I was given my novel to the sound of gunfire in the west, to the sight of an old Christian making fun of the Ashura and of the Shi’a who now owned his city and his country, wearing a comedy fez and mock self-flagellating with a plastic whip.

Biblioklept: Was it always in your head to introduce the vampire element into the plot? How did that come about?

CS: Well, when I started Anti Lebanon I started with the scene in the amusement park with my protagonist Leon, a security guard there who’s fallen asleep and wakes up to “a dead and freakish still.” I had all these materials in my head for the book:

I had the country, my obsession with it. I had the this amazing historical moment when Hezbollah took over, in response to the Sunni-heavy government under Saad Hariri trying to control them, to shut down their illegal communications network. The revenge of the Shia in Lebanon against the Sunni who have always looked down upon them. And the first time the seemingly untouchable Hezbollah turned their guns against fellow Lebanese. It was a complex contemporary political and military moment that I think novels have a particular genius in showing us, if novelists would only look at them.

I had Christians in Lebanon after the civil war. All the tragedy and the bloodthirstiness of Lebanese Christianity. The decline of things, which I’m very attracted to: pride in decline. And I had this character of Leon’s father very powerfully in mind: a big Christian, both physically and in personality; a security guard, a burly, charismatic, working man and leader and a civil war veteran. A man I became friendly with in east Beirut. One of those powerful male figures in our lives we feel are untouchable and always right. (“Three times jujitsu champion of Lebanon during the civil war; when? who remembers; who knows now.”) I had the contradictions creeping into his life, as the Hezbollah he has to support, because the Christian party he supports has aligned with them, do something very ambiguous and worrying.

But there was something missing, some binding element, or catalyst, some next level shit that could help the novel embody the whole messy idea. Somehow represent the addiction to violence, the ancestral handing-down of this kind of obligation to violence, and the sense of the blood in the soil always under your feet in Beirut. Walking a particular corner, looking at the men outside Phalange headquarters, and knowing Black Saturday started here where you stand. I had always wanted to write a vampire, one day. It was right in front of me, begging me to see it.

When I finally realised it, that was when the problems started.

Biblioklept: Okay—you can’t just stop there. Tell us about those problems.

CS: Oh my God. It would seem so silly and all writers’ problems when it comes to actually writing are the same or similar. Not finding a voice. Doubting your own voice. Time. Jobs. Debt. Money. Doubt, principally. The only mentionable and salvageable things, because they are, in retrospect, possibly funny, are the symptoms: I became convinced I was losing my hair. I went to an ER one day and had to abashedly (I was then a 36-year-old heavy smoker) tell the doctor (kind of leaning into him, and making an “I know this sounds stupid” face) that I thought I might be having a heart attack.

You don’t want to go into the emotions you feel when you enter a hospital ER thinking you’re having a heart attack and leave with some over-the-counter Gaviscon and one rogue ECG electrode still stuck to your ribs.

There were pressures. The worst were probably internal. But when my daughter was born she slept a lot of the time and I had a sudden superhuman burst of clarity and focus and went through the entire manuscript again stem to stern, took two weeks off work to rewrite one of the Japan sequences where Beirut and Lebanon had slipped off the page and the book had gotten floaty and lost, and then almost immediately I submitted it to Jack Shoemaker.

Biblioklept: The final third of the book, those Japan sequences and the Israel bit, those are some of my favorites. I think there’s a lot of picaresque energy there. Was Jack Shoemaker your editor as well as publisher?

CS: Jack is my first reader, then there’s a second, but he’s never edited me as a copy editor edits. He’s always been my greatest advocate and is an amazing reader (and his list speaks for itself) but I don’t even know if he edits anyone any more. My editor on the first two books was the incomparable Trish Hoard, who was then one half of Shoemaker and Hoard before Jack got Counterpoint back.

Biblioklept: Were you ever pressured or tempted to play up the vampire aspect of the novel as a means to, I don’t know, bolster its commercial appeal?

CS: Well I started the book in 2008 and very soon after Twilight hunched and slouched and pouted into my awareness and after about six seconds of thinking “oh cool, trickledown” I realised it was an unmitigated disaster for me. Not only was my vampirism in Anti Lebanon supposed to be truly terrifying – and geopolitical, and religious – plus it had to do with sex but was also kind of unsexy in the easier ways (in that the sex in the book is constrained by religion, and is difficult and a bit sad and more about relief and frustration), but it was also the kind of vampirism I actually believed in: a nearly physical manifestation of a metaphor that is so persistent and pervasive and persuasive: a shade.

So I asked myself would the audience of Twilight and True Blood really want to broaden their fun base into a novel about Beirut, Hezbollah, the Lebanese civil war and the Christian exodus, and I decided probably not. So I thought so I’m writing the wrong kind of vampirism to speak to these people, and too much vampirism to speak to everybody else who’s thoroughly sick of it, and I’m screwed when it comes to publication.

But the metaphor was so true and so right and the novel started to click “like a fucking Geiger counter” as dfw would have it, so I really had no choice. I stuck by the kind of vampire the book was into and the kind of questions the book was asking: is he or is he not a vampire? What is a vampire really? If the historical record clearly demonstrates so many acts that are far, far worse and the cause of so much more blood spilled than any act of vampirism, then what kind of creature is a vampire? Is he mourning?

Late in the war a Christian priest was quoted as saying, “For a long time it was fun. Playing in our own blood.” I put alongside this a Patrick Chauvel photograph of a priest in robes standing in a pile of shells firing a 50-cal. machine gun in south Lebanon in 1985. The glee on his face. A soldier beside him with his face in his hand. The material in the “pyr” chapter, about PLO soldiers ransacking the the Christian mausoleums in Damour: it was all true. What more evidence did I need? All good lit, music, film goes against what prevailing fashions, even if they’re dealing in the same ostensible material.

And here we recognize conclusive evidence of pyr: The process of exection extended to the dead. The Damour cemetery was invaded and it was a rout. They rooted out the corpsesnipers from the mausoleums, dragged the skeletonsoldiers from their elaborate Christian coffins, stripped them of their mortuary best, murdered their cadavers, pulling rib from rib, penetrating the vacant insides to locate and despoil and exect the very Christian soul.

—Anti Lebanon – 150

Plus, in terms of “commercial appeal”, Etienne Sakr said another smart thing:

“When you are fighting you either follow the cause and don’t get the money, or you follow the money and lose the cause.”

Biblioklept: There’s a lot in the book that makes the reader go, “Wait, what?” Is this real? Is this really happening to Leon? Is this in his head?” The section in Israel for example . . .

CS: The idea became for me the discipline of this particular novel, which was to attempt to analogise contemporary Christian Lebanon while invoking and revitalising the vampire genre. [Note: some spoilers follow in this response only]

Leon is a young Christian in a very precarious situation. Yet paradoxically he and his father are security guards. (The novel is riddled with them – and Leon kills one later.) With some fellow Christians he commits, through a fin de siècle hedonism, accident and the absence of inhibition bred of desperation and overfamiliarity, a violent crime against, not a rival sect, but a fellow Christian. This is the vulnerable, damaged Armenian jeweller Frederick Zakarian. And, believing him dead, as they try to dispose of his body Zakarian, tied up but seemingly still alive, bites him. With the only weapon Zakarian has any longer. Teeth.

It is here (though for close readers the inevitability is triggered at the threshold to Zakarian’s workshop) that the narrative attempts to successfully double or mirror Leon – as vampire, as criminal, as victim, failed son, inheritor of paternal sin and a psychology overdetermined by violence, and simply as mourning brother. To me, being undead and mourning share a lot of the same qualities.

There was a wonderful 1984 Playboy interview with the Druze leader Walid Jumblatt (despite the blood and compromise on his hands a very interesting polymath and political genius, who showed William Dalrymple the rooms of priceless religious artifacts he’d saved from the war – see Dalrymple’s excellent From the Holy Mountain). I had it as an epigraph for a time:

Q: How do you deal with those feelings on a personal level? How does it feel not to know if you or your family will live through another day?

A: We become inhuman. We no longer respond to normal human feelings.

—interview with Walid Jumblatt, Playboy 1984

Leon flees Lebanon when it becomes clear the Armenians, missing their man and the jewels he was working on (destined for Iranians), are talking to the Christians of Beirut who have decades-old scores to settle against Leon’s father for his alliances in the civil war. The factions begin to align around money. Leon’s flight from Lebanon also simply mirrors in a particular sense the horrible inevitability of the more general Christian flight after 1400 continuous years of settlement in that one place.

The scenes in Israel you mention, that feature a psychic during immigration questioning at the Allenby Bridge border: these are simply in-context extrapolations of the already wildly implausible real we’re all struggling to absorb.

Biblioklept: Can you tell us what you’re working on now? I know you’ve been working on something new…

CS: [sotto voce] Right now I’m writer in residence at Victoria University of Wellington’s International Institute of Modern Letters, and the generosity and good company of students and staff here have allowed me to get 60,000 words into a new novel set in a medical journal in London. It’s a social comedy in the world of work, with a Straw Dogs strand and a healthy skepticism for the whole project of “a social comedy in the world of work” driving the plot—like Saki meeting Julio Cortazar in an argument over grammar and style in a London pub full of eccentric, driven healthcare professionals.

Biblioklept: Have you ever stolen a book?

CS: I once rescued Burroughs’ Cities of the Red Night (in English) from a trashcan in Tokyo (and stole a great nickname for one of my dark drinking lazy boys: “Pazuzu, of the rotting genitals’). I was also prohibited from graduating from Victoria due to more than $1000 in overdue fees from the library. One of the books was David Bergamini’s astonishing Japan’s Imperial Conspiracy. So I have no regrets.

Kevin Thomas’s new book Horn! (from OR Books) collects the book reviews he’s been doing for the past few years at the Rumpus. Kevin reviews new books (and occasionally reissues) in comic strip form. Over a series of emails, Kevin talked with me about his process, how he got started, the books that have stuck with him the most over the years, and his theory that The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou is a secret remake of Three Amigos! Find Kevin on Goodreads,Twitter, and Tumblr.

Kevin Thomas’s new book Horn! (from OR Books) collects the book reviews he’s been doing for the past few years at the Rumpus. Kevin reviews new books (and occasionally reissues) in comic strip form. Over a series of emails, Kevin talked with me about his process, how he got started, the books that have stuck with him the most over the years, and his theory that The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou is a secret remake of Three Amigos! Find Kevin on Goodreads,Twitter, and Tumblr.

I was deeply impressed by the short stories in Jessica Hollander’s In These Times the Home Is a Tired Place (

I was deeply impressed by the short stories in Jessica Hollander’s In These Times the Home Is a Tired Place (

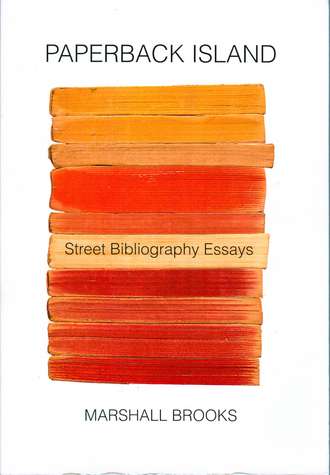

Marshall Brooks’s recent collection of memoir-essays Paperback Island explores the ways that friendship and place influence what we read, how we read, and how we make—and keep—books. Marshall began his career in publishing in 1971, reading manuscripts for Harry Smith at his legendary publishing house The Smith. In 1979 he created Arts End Press. Subtitled Street Bibliography Essays, Marshall’s latest book provides fascinating insights into a world of post-Beat publishing that is slowly slipping away (that is, aside from in memories and books). Marshall was kind enough to talk to me over a series of emails. He was generous and thoughtful, and also interested in my own life—in my kids, in my reading and teaching, but also in the bookstores in my community. It was a pleasure to talk with him. The end of our email exchange found him in NYC, attending a memorial for Harry Smith. Marshall lives in Vermont with his wife and two sons. Check out

Marshall Brooks’s recent collection of memoir-essays Paperback Island explores the ways that friendship and place influence what we read, how we read, and how we make—and keep—books. Marshall began his career in publishing in 1971, reading manuscripts for Harry Smith at his legendary publishing house The Smith. In 1979 he created Arts End Press. Subtitled Street Bibliography Essays, Marshall’s latest book provides fascinating insights into a world of post-Beat publishing that is slowly slipping away (that is, aside from in memories and books). Marshall was kind enough to talk to me over a series of emails. He was generous and thoughtful, and also interested in my own life—in my kids, in my reading and teaching, but also in the bookstores in my community. It was a pleasure to talk with him. The end of our email exchange found him in NYC, attending a memorial for Harry Smith. Marshall lives in Vermont with his wife and two sons. Check out

Biblioklept: Did you prefer to use as much of the subject’s language as possible? Maybe I’m getting into what you described as “the second difficult thing” — how much of yourself do you see in the pieces? I think there’s clearly a voice, a tone that unifies the pieces . . . I’m curious how much of the process was crafting or editing or revising or repurposing the subject’s original language…

Biblioklept: Did you prefer to use as much of the subject’s language as possible? Maybe I’m getting into what you described as “the second difficult thing” — how much of yourself do you see in the pieces? I think there’s clearly a voice, a tone that unifies the pieces . . . I’m curious how much of the process was crafting or editing or revising or repurposing the subject’s original language…

Joshua Henkin’s new novel, The World Without You, tells the story of the Frankels, a large Jewish American family who gather over the Fourth of July weekend to mourn the death of their son Leo, a journalist who was kidnapped and then murdered in Iraq. The World Without You is Henkin’s third novel after Matrimony and Swimming Across the Hudson. Henkin directs the MFA program in Fiction Writing at Brooklyn College. The World Without You is new in hardback from

Joshua Henkin’s new novel, The World Without You, tells the story of the Frankels, a large Jewish American family who gather over the Fourth of July weekend to mourn the death of their son Leo, a journalist who was kidnapped and then murdered in Iraq. The World Without You is Henkin’s third novel after Matrimony and Swimming Across the Hudson. Henkin directs the MFA program in Fiction Writing at Brooklyn College. The World Without You is new in hardback from  Biblioklept: The World Without You is conveyed in the present tense. I’m curious what led you to compose in the present tense, or if you drafted parts of the novel in the past tense—what advantages can the present tense offer the writer and reader? What are its limitations?

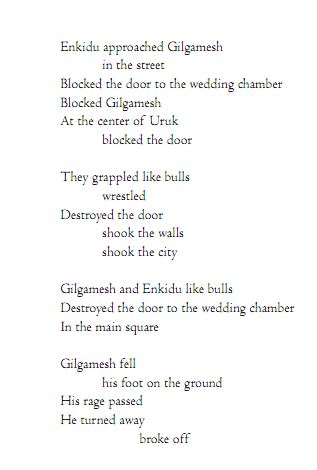

Biblioklept: The World Without You is conveyed in the present tense. I’m curious what led you to compose in the present tense, or if you drafted parts of the novel in the past tense—what advantages can the present tense offer the writer and reader? What are its limitations? Stuart Kendall is the author of several books, including The Ends of Art and Design, a work that examines the role of experience-events in the post-subjective world, and Georges Bataille, a critical biography of that influential author. Stuart also edited and contributed to Terrence Malick: Film and Philosophy. Stuart has produced and published numerous translations, including works by Bataille, Guy Debord, Paul Éluard, and Maurice Blanchot. His latest translation is a telling of Gilgamesh, one that casts the ancient epic poem in modernist poetry. Stuart has taught at several universities and colleges, including Boston University and the California College of the Arts, where he is currently Chair of Critical Studies. Stuart was kind enough to talk to me about Gilgamesh—and Malick—over a series of emails. You can read more about Stuart’s work at his

Stuart Kendall is the author of several books, including The Ends of Art and Design, a work that examines the role of experience-events in the post-subjective world, and Georges Bataille, a critical biography of that influential author. Stuart also edited and contributed to Terrence Malick: Film and Philosophy. Stuart has produced and published numerous translations, including works by Bataille, Guy Debord, Paul Éluard, and Maurice Blanchot. His latest translation is a telling of Gilgamesh, one that casts the ancient epic poem in modernist poetry. Stuart has taught at several universities and colleges, including Boston University and the California College of the Arts, where he is currently Chair of Critical Studies. Stuart was kind enough to talk to me about Gilgamesh—and Malick—over a series of emails. You can read more about Stuart’s work at his

In part notions like these are so deeply disturbing because they cut to the core of our perspective on reality. As part of a thoroughly pagan text, Gilgamesh consistently encounters gods in the things and people around him. But he also fears some of those same things as much as he savors others. The text provides rich details about objects and animals. It shows people looking at and enjoying other people. It is a book of sensual celebration as much as it is a journey into despair and the two are related, as I suggested just now: death is to be feared because life is so very full.

In part notions like these are so deeply disturbing because they cut to the core of our perspective on reality. As part of a thoroughly pagan text, Gilgamesh consistently encounters gods in the things and people around him. But he also fears some of those same things as much as he savors others. The text provides rich details about objects and animals. It shows people looking at and enjoying other people. It is a book of sensual celebration as much as it is a journey into despair and the two are related, as I suggested just now: death is to be feared because life is so very full. Adam Novy’s debut novel The Avian Gospels is one of the best novels I’ve read this year, and one of the best contemporary novels I’ve read in ages. It’s a surreal dystopian magical romance set against the backdrop of political and cultural repression, violent rebellion, torture, family, and birds. Lots and lots of birds. (

Adam Novy’s debut novel The Avian Gospels is one of the best novels I’ve read this year, and one of the best contemporary novels I’ve read in ages. It’s a surreal dystopian magical romance set against the backdrop of political and cultural repression, violent rebellion, torture, family, and birds. Lots and lots of birds. ( Biblioklept: It’s interesting that you mention the LOTR movies as a kind of ambient influence, because they were pretty ubiquitous in the last decade—and there’s so much of the last decade’s zeitgeist in your book: torture, despotism, political and cultural repression, the plight of a refugee class, the idea of “green zones,” etc. You foreground these themes by crafting Gospels as a kind of dystopian novel with elements of magical realism, but it’s also very much a novel about family, and even a love story. (By sheer coincidence I watched the restored edit of Metropolis in the same time frame that I was reading Gospels, and saw so many echoes there). How conscious were you of genre conventions? I’m curious because your book sometimes blends genre tropes, sometimes blurs them, and sometimes straight-up explodes them . . .

Biblioklept: It’s interesting that you mention the LOTR movies as a kind of ambient influence, because they were pretty ubiquitous in the last decade—and there’s so much of the last decade’s zeitgeist in your book: torture, despotism, political and cultural repression, the plight of a refugee class, the idea of “green zones,” etc. You foreground these themes by crafting Gospels as a kind of dystopian novel with elements of magical realism, but it’s also very much a novel about family, and even a love story. (By sheer coincidence I watched the restored edit of Metropolis in the same time frame that I was reading Gospels, and saw so many echoes there). How conscious were you of genre conventions? I’m curious because your book sometimes blends genre tropes, sometimes blurs them, and sometimes straight-up explodes them . . .