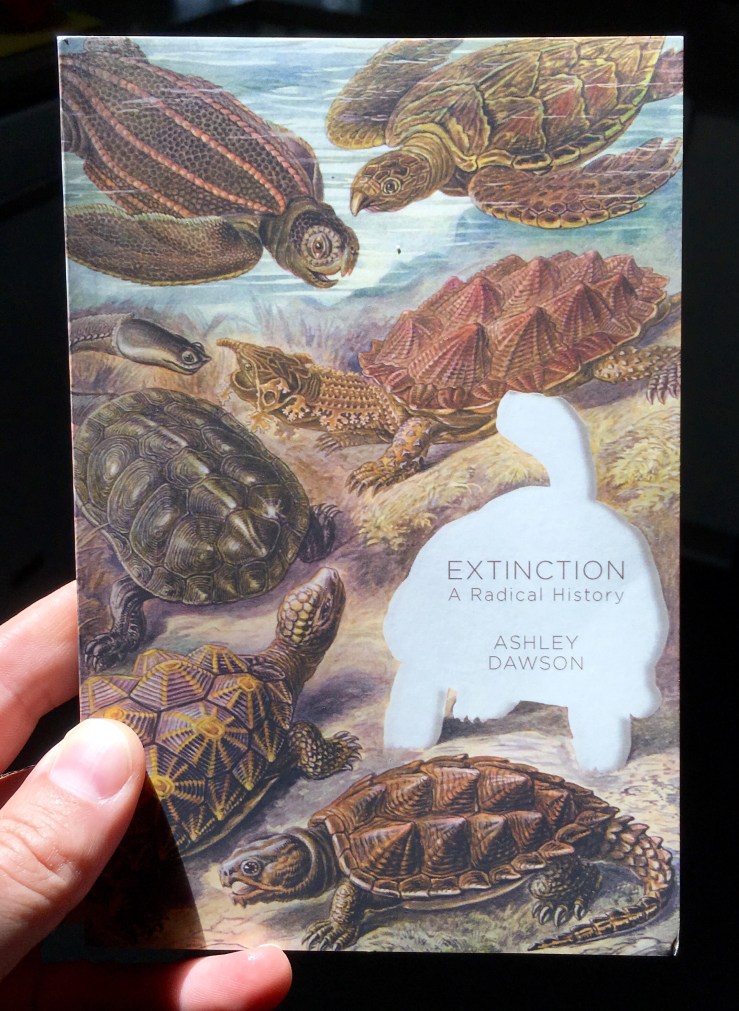

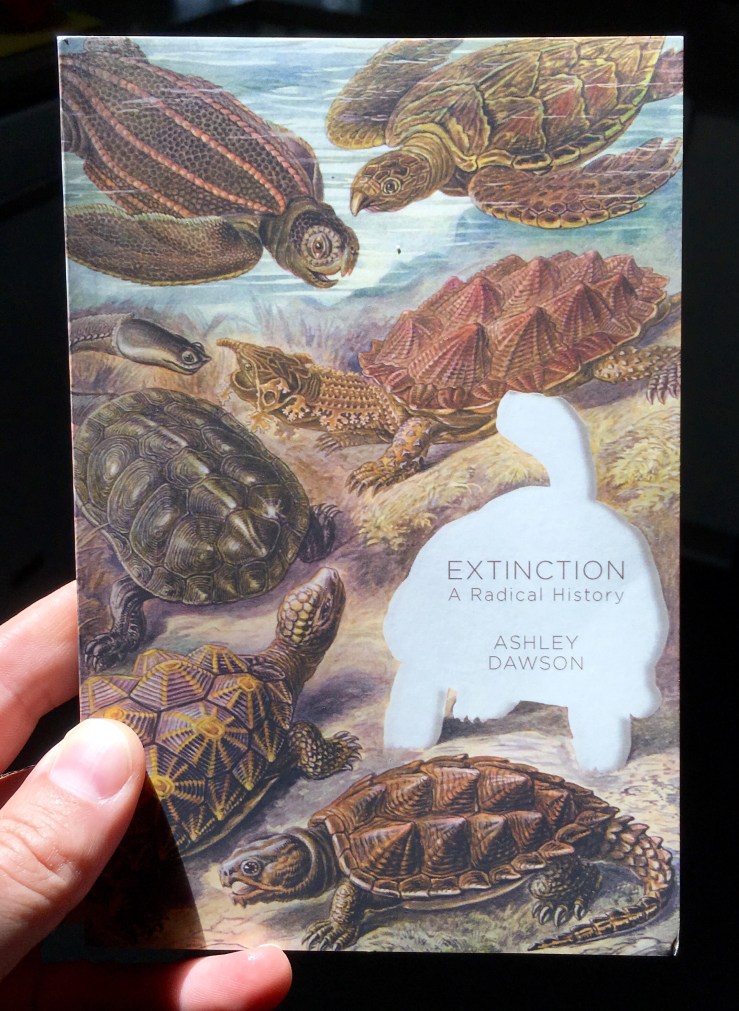

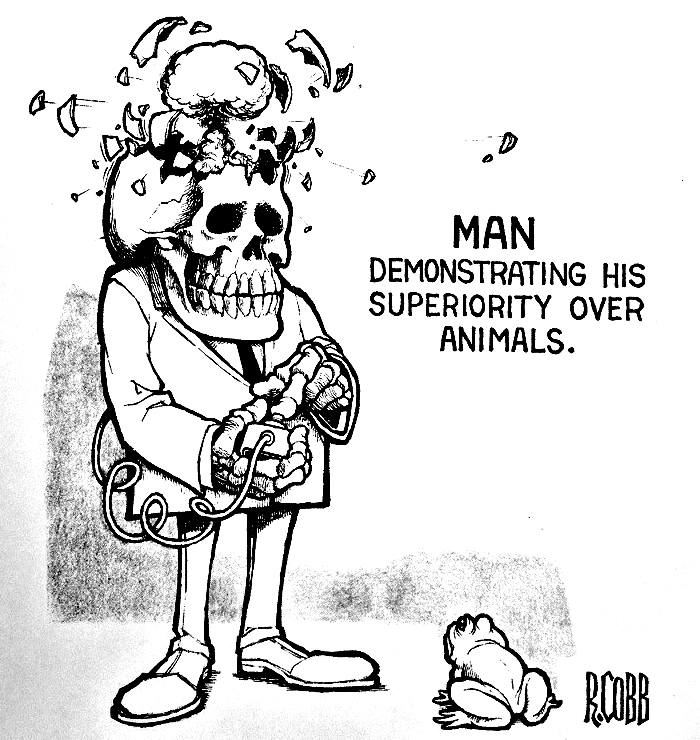

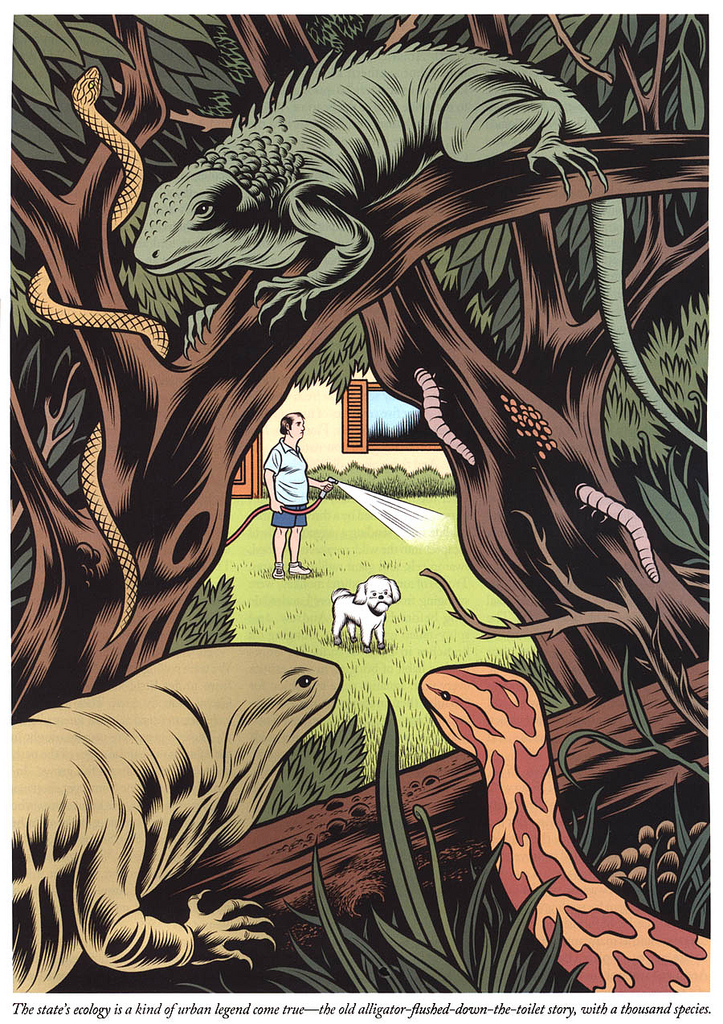

Reading the introduction to Ashley Dawson’s Extinction: A Radical History this afternoon (forthcoming from OR Books), I felt a surreal yet nevertheless familiar twinge of apocalypse anxiety creeping into my right eye, where it tussled around. Is unnerved the metaphor I look for, here? Or is my response more literal? “Extinction is the product of a global attack on the commons, the great trove of air, water, plants and creatures, as well as collectively created cultural forms such as language, that have been regarded traditionally as the inheritance of humanity as a whole,” writes Dawson, and I nod my head. Dawson continues: “capital of course depends on continuous commodification of this environment to sustain its growth.” I nod some more. “Indeed, there is no clearer example of the tendency of capital accumulation to destroy its own conditions of reproduction than the sixth extinction.” More nodding, more anxiety.

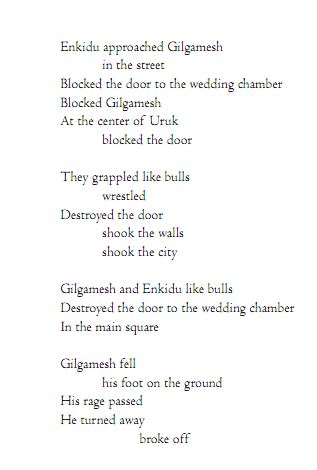

Chapter 2 of Extinction, “An Etiology of the Present Catastrophe,” assuages (not its intent, thank gawd) some of my anxiety by beginning with a passage from old ancient historical literature. Dawson gives us a passage from The Epic of Gilgamesh; we get Gilgamesh and his homeboy Enkidu killing the forest guardian spirit Humbaba. I’m more at home in literature, in history, outside of the awful present (I’m thinking that later in the book, in chapters titled “Anti-Extinction” and “Radical Conservation,” that Dawson might like call on me to do something other than to extol the virtues of Thoreau and Emerson to college sophomores. (And nod in agreement with him)).

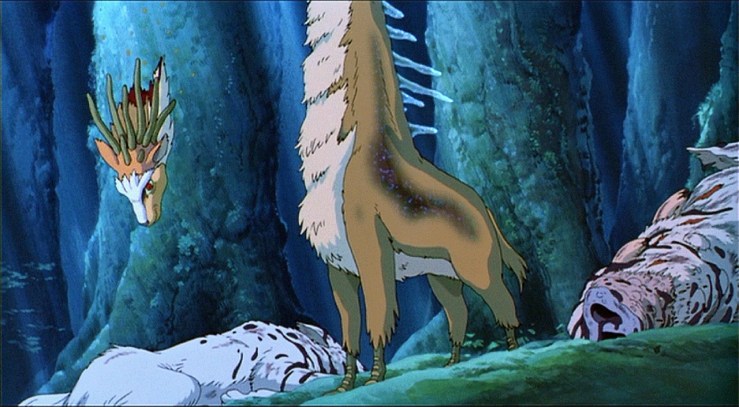

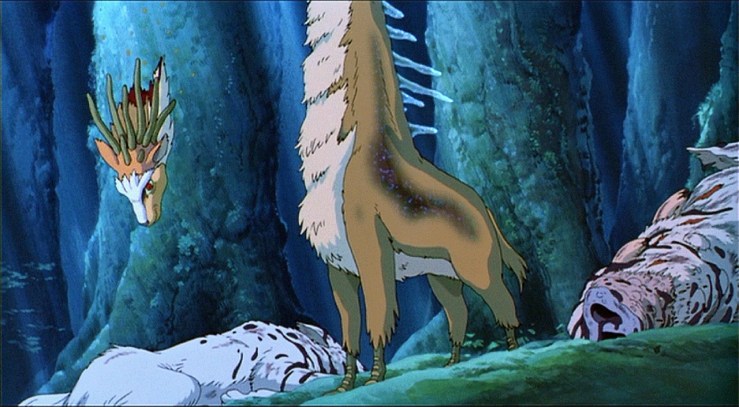

But so and anyway, reading this prefatory paragraph from Gilgamesh, I made the immediate imaginative leap that literature licenses me: the episode that Dawson has invoked, this city-statesman vs. nature narrative featuring Gilgamesh straight up beheading the forest protector—well, that’s the central conflict/plot in Hayao Miyazki’s 1997 film Mononoke-hime (rendered in English as Princess Mononoke, but I think better translated as Spirit-Monster Wolfchild or something like that, although no one asked me).

More on that in a second, but first, Dawson again, from the middle of “An Etiology of the Present Catastrophe,” wherein we move from literature to history to the present:

The violence generated by what geologists call the Holocene epoch was directed not just at other human beings but also at nature. Indeed what is perhaps humanity’s first work of literature, the Epic of Gilgamesh (1800 BCE), hinges on a mythic battle with natural forces. In the epic, the protagonist Gilgamesh, not content with having built the walls of his city-state, seeks immortality by fighting and beheading Humbaba, a giant spirit who protects the sacred cedar groves of Lebanon. Gilgamesh’s victory over Humbaba is a pyrrhic one, for it causes the god of wind and storm to curse Gilgamesh. We know from written records of the period that Gilgamesh’s defeat of the tree god reflects real ecological pressures on the Sumerian empire of the time. As the empire expanded, it exhausted its early sources of timber. Sumerian warriors were consequently forced to travel to the distant mountains to the north in order to harvest cedar and pine trees, which they then ferried down the river to Sumer. These journeys were perilous since tribes who populated the mountains resisted the Sumerians’ deforestation of their land.

Dawson goes on to to detail how the Sumerians’ short-sighted, expansion-oriented agricultural methods led to the downfall of their empire: A scarcity of timber and farming practices that led to a “salt-soaked earth” led to Iraq’s modern deserts.

Before my eye starts twitching again let me return (retreat) to Miyazaki—

—well, I watched Princess Mononoke just this Saturday, the Saturday before Easter—for like the first time in a decade. (We watch his films all the time with our kids (Ponyo, Totoro, and Spirited Away especially), but not Mononoke, which is too abject and violent yet for their tender years. And not Porco Rosso, which isn’t really for kids. Or The Wind Rises).

Anyway: So: Mononoke, I was thinking, rewatching it, was/is this wonderfully, beautiful, aesthetically astonishing take on the beginning of industrialization, and the weaponization of industry, and, like man vs nature, in a primordial sense. It’s also a Japanese Western, a meditation on purity and defilement, and a study of sorts on a feral child. Not having seen it in some time, I was perhaps most struck by how complex, brave, and intriguing I found the industrialist arms-designer/manufacturer Lady Eboshi (voiced by Minnie Driver). She fights against the forest gods, she destroys and pollutes nature, she creates new weapons capable of killing people with a proficiency not yet seen on this earth. And yet at the same time, she finds a home for lepers and prostitutes—and not just a home, but a reason to be, an agency, an existential calling outside of the feudal system that would otherwise reject them. She’s the most human character in the film, perhaps. Miyazaki’s villains are rarely absolute. They are gray, human. And in their complicated, seemingly realistic humanity, I find the consolation of fantasy, yes?

So in viewing Mononoke this Easter eve—well maybe it was the wine I drank transubstantiating (or do I mean consubstantiating?) my blurred vision toward something more (an aesthetic illusion)—

—or and but anyway, so in Mononoke, I found some kind of synthesis, some kind of reconciliation between the wolfchild (Princess Mononoke, human-divine emissary of the old gods, the human not in nature but of and for nature) and the film’s protagonist (the self-exiled marked man Ashitaka—a cursed wanderer like Cain).

But no redemption. Or maybe only aesthetic redemption—which is ultimately anaesthetic, no? The rebirth in Mononoke—spoilers, maybe sorry—well the rebirth is predicated on the same sacrifices (same same but different) detailed in the Easter story. Self-sacrifice: Obliteration of self. The tree-god-guardian—as in Gilgamesh—is beheaded. But Miyazaki contrives a heroic restoration of the godhead, one that turns the literal megafauna creature into a metaphor, an idea—a concept of nature to be attended to—stewarded by—humankind. This is wish-fulfillment, of course.

But hey and so: that fantastic wonderful megafauna, eh? They range and lumber and speak and act and assert agency throughout Mononoke. Boars, wolves, elk. A kirin. Hell, apes. In Extinction, Dawson takes us through the mass extinction of the megafauna that once trudged and bounded over the earth, detailing the “Pleistocene wave of megadeath.” (Should I note that saber tooth tigers and giant sloths and wooly mammoths populated my childhood fantasies more than any T-rex or triceratops?). We—that is humans—we are the big animals now, elephants be damned! (Dawson opens his book with the shocking line “His face was hacked off.” This, in reference to the elephant Satao, felled by poachers). Is it my dreams and fantasies that I find consolation in? In aesthetics? In the crusty rime of religion that sticks to my consciousness?

Extinction frightens me—wait, I said that already, forgive me, I’ve been applying anaesthetics, okay—Dawson’s take is real, urgent, vital. It makes me face that I prefer my ecological criticism couched in the fantasy of the fantasy-past (Mononoke) or the doomed-but-hey-maybe-not-so-doomed-future (I’ll call here on Mononoke’s twin, Miyazaki’s 1984 epic Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, as an example). But prefer is not the right mode/verb here (and neither is the spirit of this riff, a solipsistic navel-gazing blog of myself). This failure is my failure.

Maybe skip ahead, eh?— “The struggle to preserve global biodiversity must be seen as an integral part of a broader fight to challenge an economic and social system based on feckless, suicidal, expansion,” Dawson writes later. And skimming ahead more, I see notes on regenesis, ideas toward rewilding. Dawson’s last paragraphs—damn me, I skipped way ahead, looking for rhetorical solace—point toward “a human capacity to dream and to build a more just, more biologically diverse world.” A rhetorical flourish is easy but Dawson’s claim here is real—a future requires imagination, but an imagination beyond solace, beyond consolation. Miyazaki’s ecoverses perhaps point toward an imaginative collective future—or perhaps don’t. I don’t have a rhetorical flourish to finish off this riff.

Stuart Kendall is the author of several books, including The Ends of Art and Design, a work that examines the role of experience-events in the post-subjective world, and Georges Bataille, a critical biography of that influential author. Stuart also edited and contributed to Terrence Malick: Film and Philosophy. Stuart has produced and published numerous translations, including works by Bataille, Guy Debord, Paul Éluard, and Maurice Blanchot. His latest translation is a telling of Gilgamesh, one that casts the ancient epic poem in modernist poetry. Stuart has taught at several universities and colleges, including Boston University and the California College of the Arts, where he is currently Chair of Critical Studies. Stuart was kind enough to talk to me about Gilgamesh—and Malick—over a series of emails. You can read more about Stuart’s work at his

Stuart Kendall is the author of several books, including The Ends of Art and Design, a work that examines the role of experience-events in the post-subjective world, and Georges Bataille, a critical biography of that influential author. Stuart also edited and contributed to Terrence Malick: Film and Philosophy. Stuart has produced and published numerous translations, including works by Bataille, Guy Debord, Paul Éluard, and Maurice Blanchot. His latest translation is a telling of Gilgamesh, one that casts the ancient epic poem in modernist poetry. Stuart has taught at several universities and colleges, including Boston University and the California College of the Arts, where he is currently Chair of Critical Studies. Stuart was kind enough to talk to me about Gilgamesh—and Malick—over a series of emails. You can read more about Stuart’s work at his

In part notions like these are so deeply disturbing because they cut to the core of our perspective on reality. As part of a thoroughly pagan text, Gilgamesh consistently encounters gods in the things and people around him. But he also fears some of those same things as much as he savors others. The text provides rich details about objects and animals. It shows people looking at and enjoying other people. It is a book of sensual celebration as much as it is a journey into despair and the two are related, as I suggested just now: death is to be feared because life is so very full.

In part notions like these are so deeply disturbing because they cut to the core of our perspective on reality. As part of a thoroughly pagan text, Gilgamesh consistently encounters gods in the things and people around him. But he also fears some of those same things as much as he savors others. The text provides rich details about objects and animals. It shows people looking at and enjoying other people. It is a book of sensual celebration as much as it is a journey into despair and the two are related, as I suggested just now: death is to be feared because life is so very full.