What an interesting few weeks it’s been! Here’s (some of) what I’ve been reading so far this year:

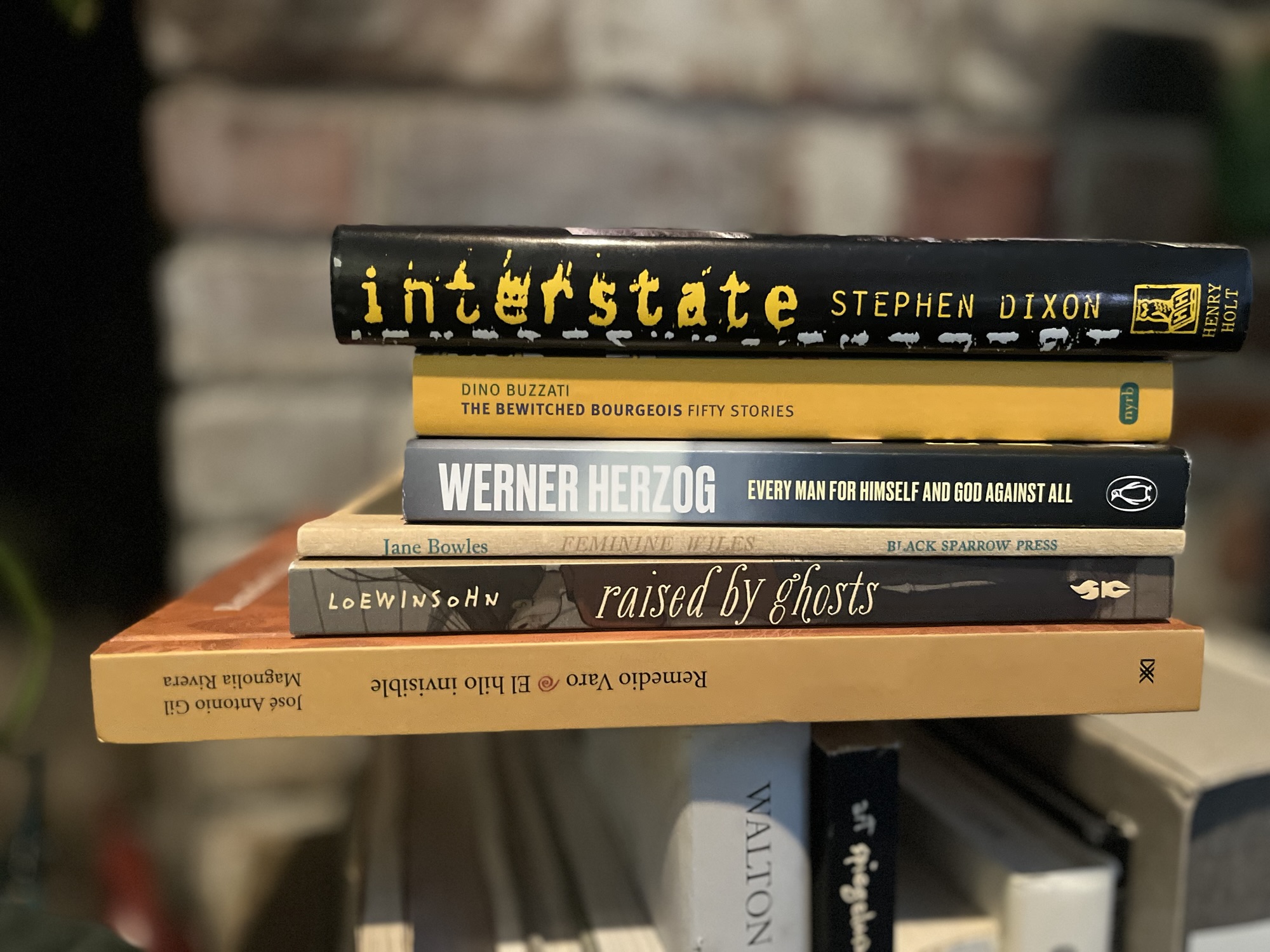

I’m in the middle of Stephen Dixon’s novel Interstate. It is a devastating, ugly, addictive, beautiful novel; I have no idea if it is “good” or not but I love it. I can’t really think of a single person I know (in real life) I could recommend it to. We played cards with some friends and one of them asked about what I was reading, and I said a novel called Interstate by this guy Stephen Dixon, and she asked of course What’s it about? and I said something, Well, this guy’s driving on the interstate with his daughters and two guys in a van pull up along side him and start shooting at them, killing his younger daughter–this happens in like, the first few paragraphs–and then we see how this event destroys his life–but then Dixon repeats the initial scenario like seven more times with different (but all really tragic so far) outcomes–and it’s written in this addictive vocal style that might be really off-putting to many readers, and it also makes really fascinating use of the coordinating conjunction for, which may just be a verbal tic –and it’s also really funny at times? I am not trying to sell this novel to anyone but I love it.

My reading experience of Briana Loewinsohn’s graphic novel Raised by Ghosts was kinda sorta the opposite of Dixon’s Interstate in that after I finished it I immediately pressed it on my wife and then my kids and then texted some of my oldest friends about it (oldest in the previous clause should be understood to modify the friendship, not the actual friend’s years–although we’re all getting older). We’re all getting older, all the time, and Raised by Ghosts provoked an aged nostalgia in me. I’m about half a year older than Loewinsohn and so much of her semi-autobiographical novel resonated with me. She gets everything right about what it was like to be a little bit of a weirdo at school in the nineties. There’s this wonderful passage on how important it was to get a handwritten note from a friend; there’s a page that’s nothing but a notebook page filled with band names; there’s a marvelous scene where our hero loses her shit watching You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown. I should have a proper review this week or next, but great stuff. (The whole family loved it, by the way.)

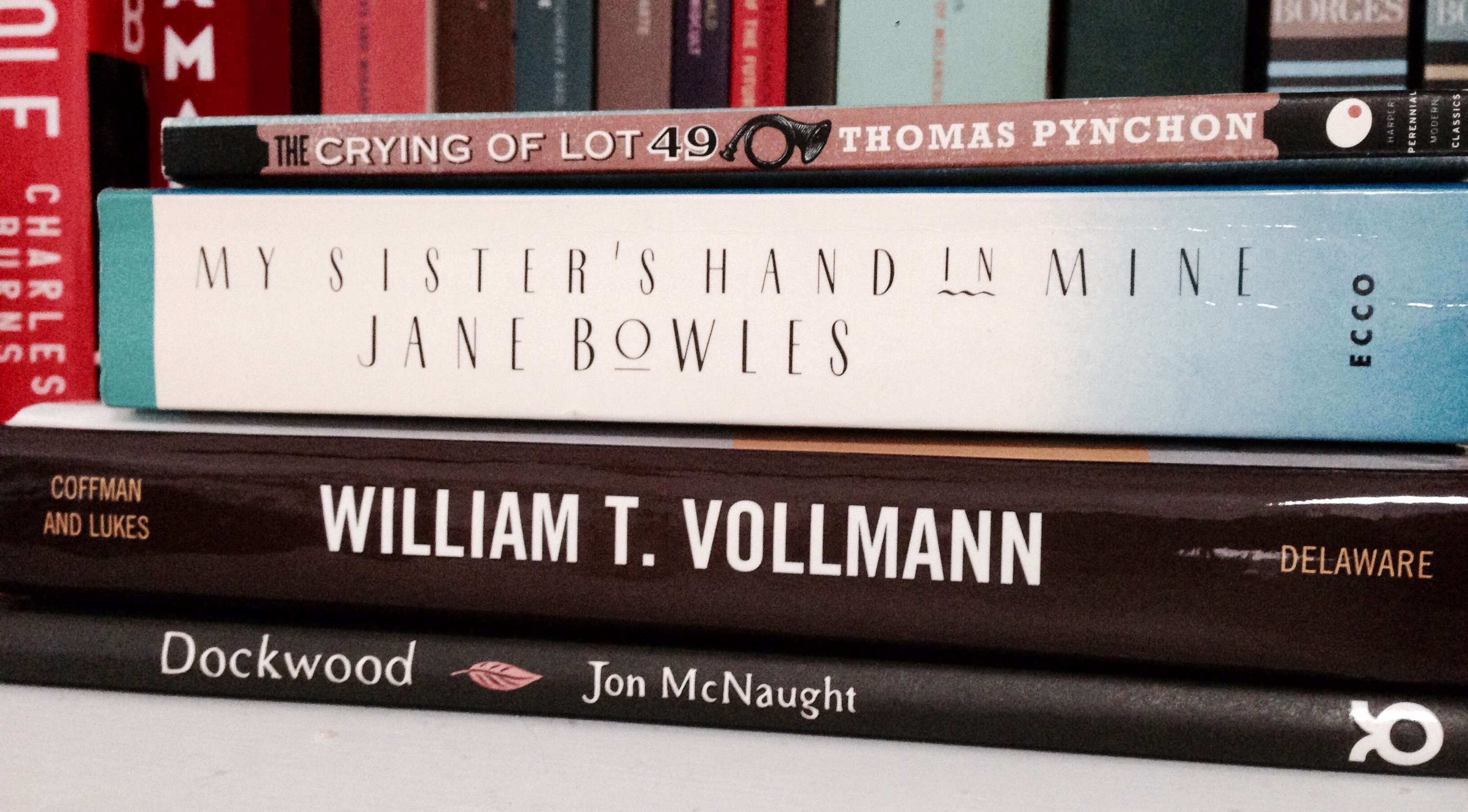

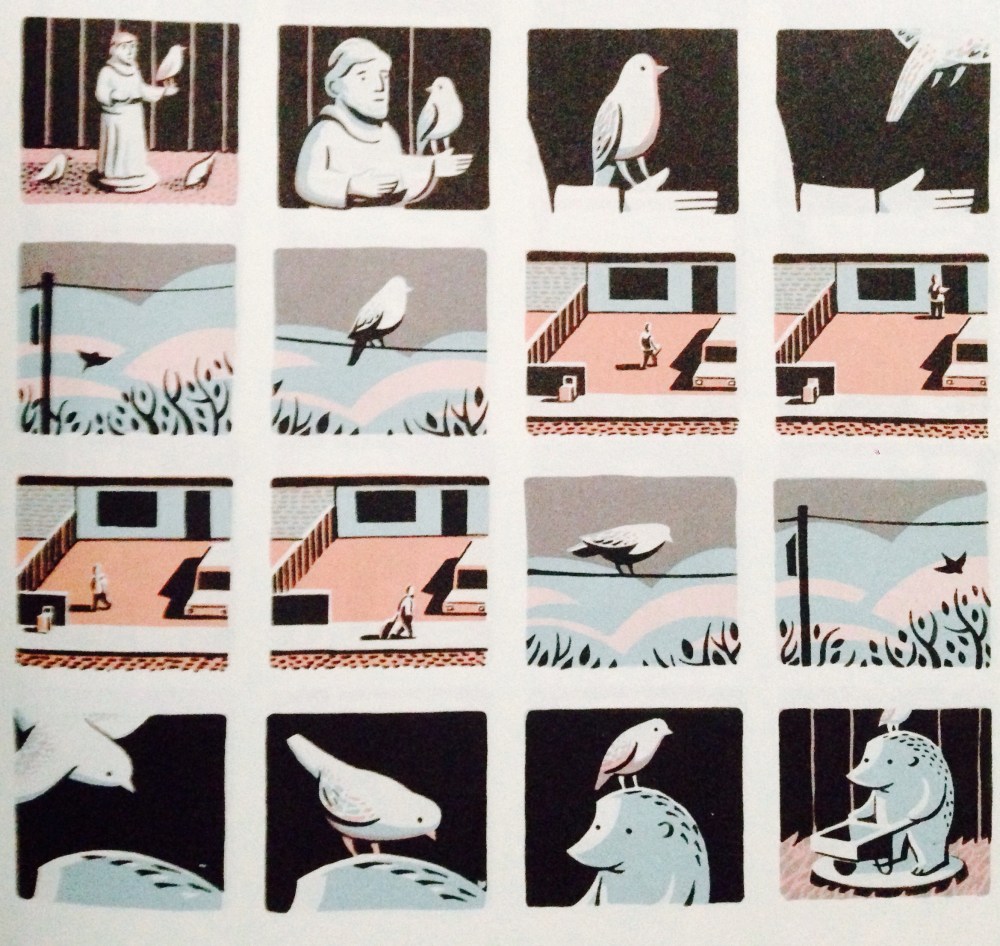

I’ve been reading a collection of Dino Buzzati short stories translated by Lawrence Venuti; my technique is to read one of the shorter stories when I feel a bit of dread or anxiety from, like, reading something else. (The collection is called The Bewitched Bourgeois by the way.) I’ve enjoyed reading them, and have especially enjoyed allowing myself to read them at random instead of following the collection’s chronological trajectory. Very Kafka, very Borges, but also very original.

Not in the picture above, but I’ve also been working my way through a digital copy of Vladimir Sorokin’s short story collection Dispatches from the District Committee, in translation by Max Lawton (and illustrated by Gregory Klassen). Great gross stuff.

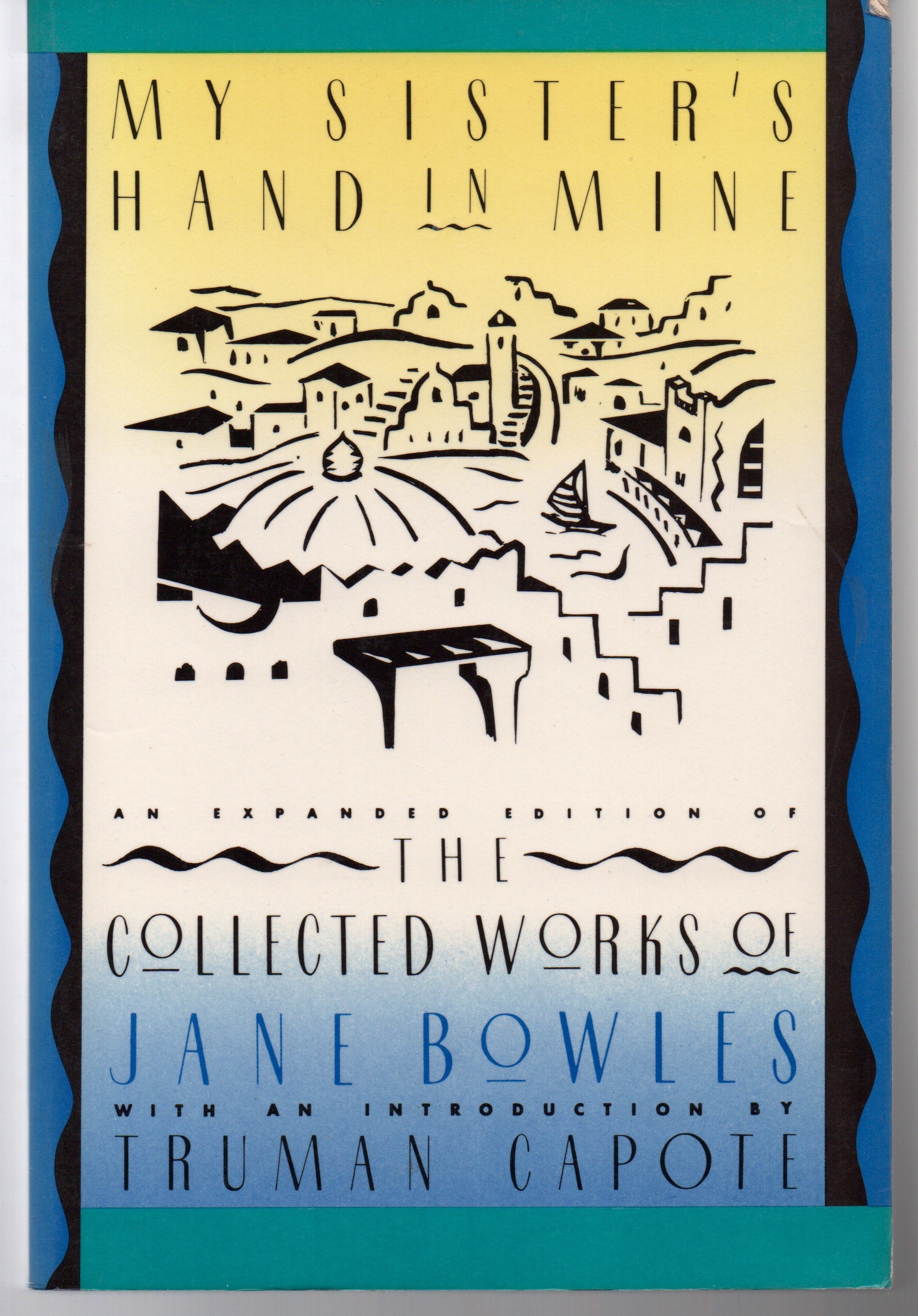

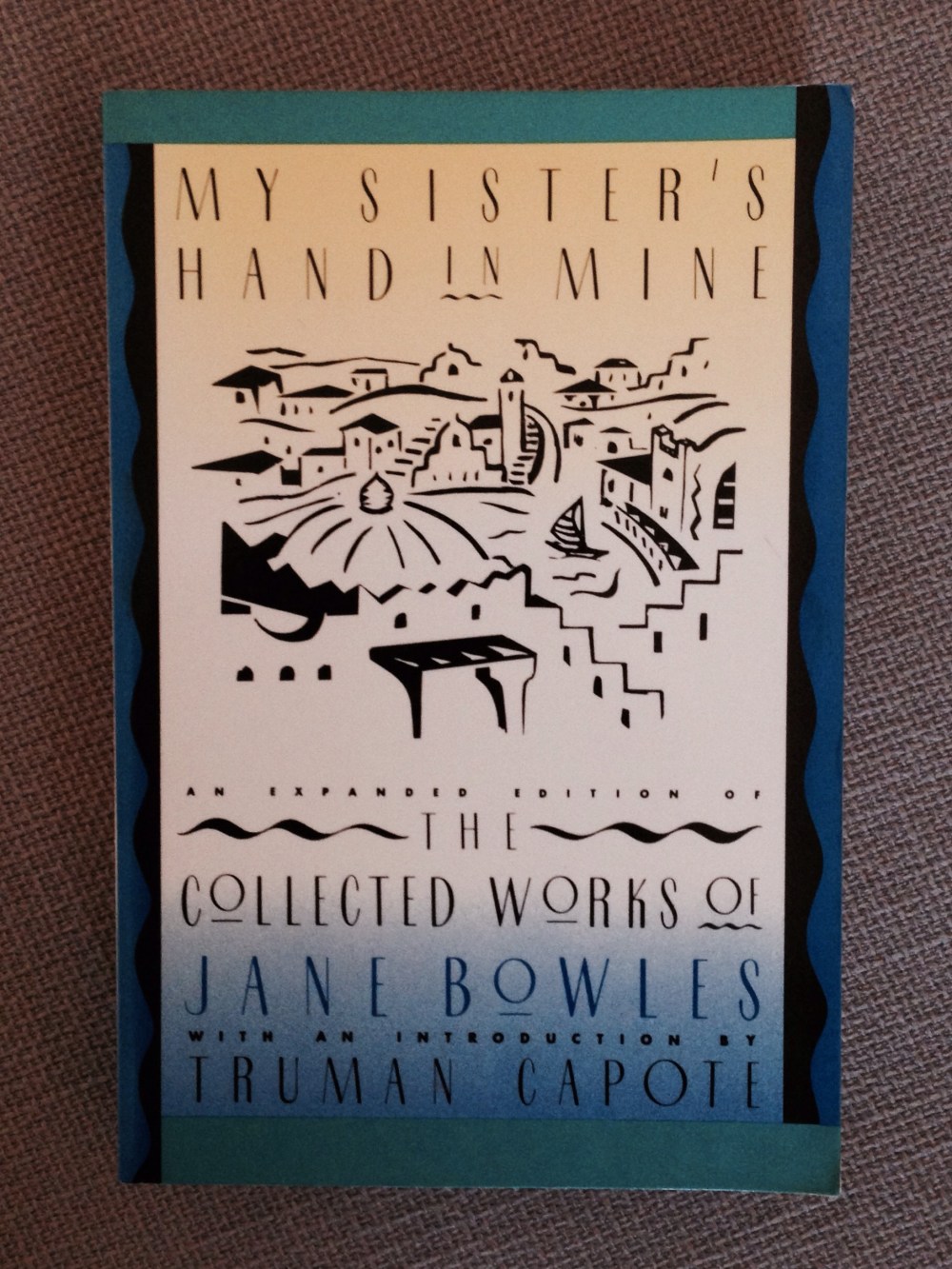

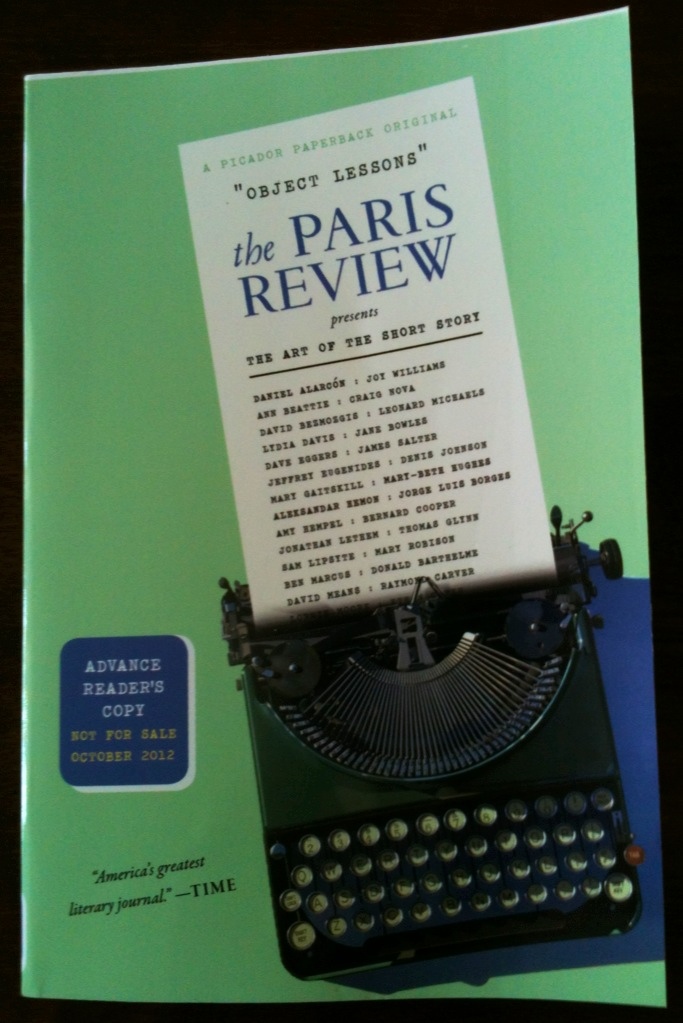

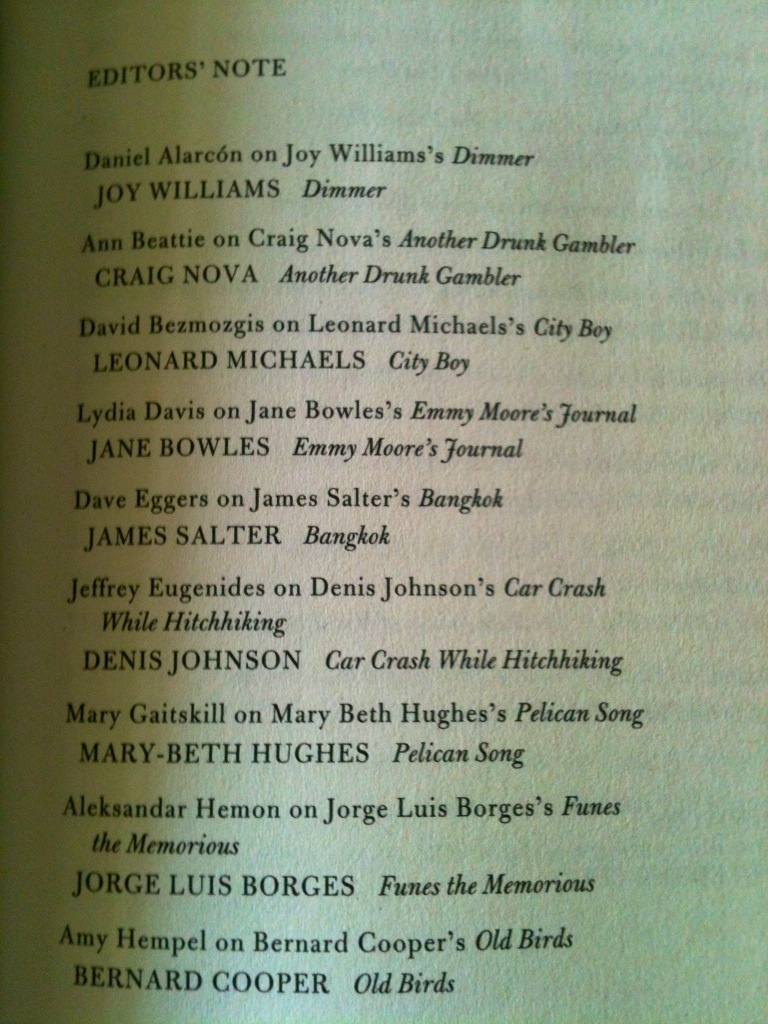

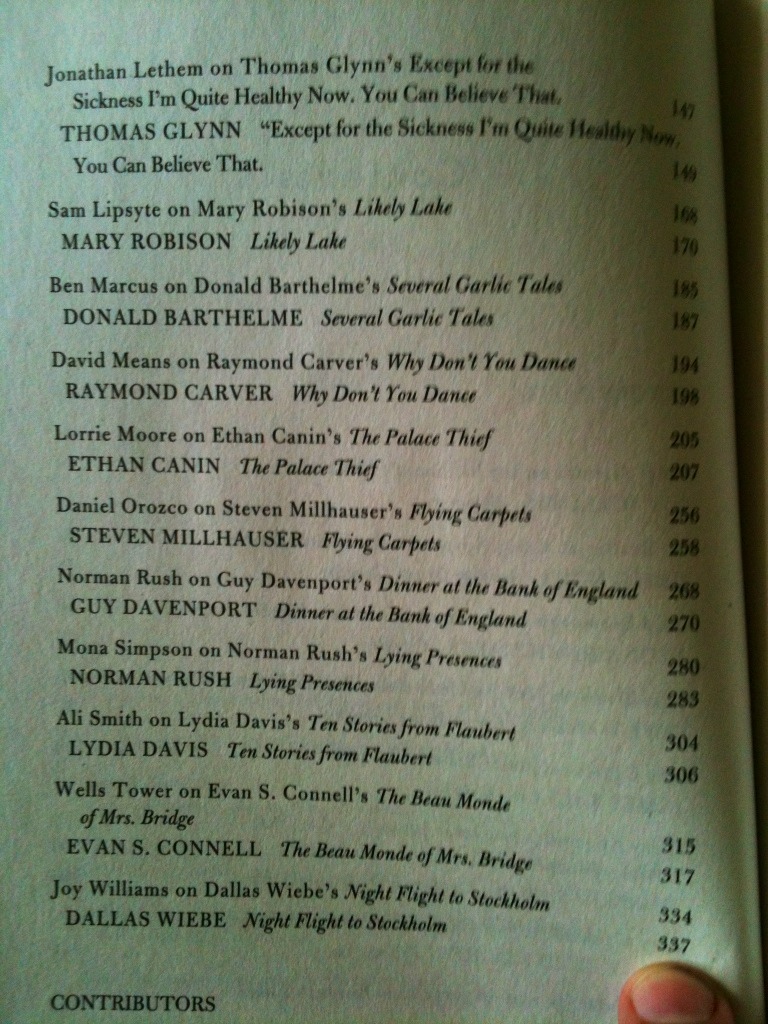

I picked up a collection of Jane Bowles’ sketches, letters, and other ephemera a few weeks ago–I love her stuff, but really it was that these were contained in the somewhat-rare Black Sparrow Press edition Feminine Wiles. I’m pretty sure all of the stuff here is collected in My Sister’s Hand in Mine, but I’ve enjoyed dipping into this one more. It’s slim, not bulky, but that bulky boy’s around her (My Sister’s) if I need him.

My uncle sent me a copy of Werner Herzog’s 2022 memoir Every Man for Himself and God Against All for Christmas (in translation by Michael Hofmann). I devoured the first few chapters and then a colleague hipped me to the fact that there’s an audiobook of Herzog reading his memoir (available on Spotify and other platforms) — so on my commute I’ve been listening to him read his own memoir, which is just amazing. Like fucking amazing. Hearing him say phrases like “the escapades of Christopher Robin, Winnie-the-Pooh, Piglet, and Eeyore” or that “chipmunks…have something consoling about them” is surreal. There are like fifty insane things that happen in every chapter, and if Dwight Garner of the failing New York Times attested that he didn’t “believe a word” of the memoir, I take the opposite tack. Everything is true, everything is permitted.

Finally, I can’t really say I’ve been “reading” Remedios Varo: El hilo invisible by Jose Antonio Gil and Magnolia Rivera. My grasp of Spanish cannot graspingly grasp too much of the Spanish (although my iPhone’s picture-text-translate thing works fine when I’m really curious), but the book is a lovely visual catalog of not just one of my favorite artist’s works (including many pieces I haven’t seen before), but also documents her visual influences. I picked it up at the Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico City back in January, still floating on the high of seeing many of Varo’s lovely paintings there that afternoon.