Yuri Herrera’s new novella Kingdom Cons condenses myth and archetype into concrete, brutal noir. Gritty and visceral, but also elegant and surreal, Herrera’s prose bristles with cinematic energy in a tale of blood magic and the relationship between power and art.

In Kingdom Cons, our central protagonist Lobo is a singer of corridos, ballads he improvises in dive bars for a few coins to survive on. Herrera paints Lobo’s backstory in quick but rich strokes that evoke a hardboiled, hardscrabble life:

The next day his father went to the other side. They waited in vain. Then his mother crossed without so much as a promise of return. They left him the accordion so he could make his way in the cantinas, and it was there he learned that while boleros can get by with a sweet face, corridos require bravado and acting out the story as you sing. He also learned the following truths: Life is a matter of time and hardship. There is a God who says Deal with it, cause this is the way it is. And perhaps the most important: Steer clear of a man about to vomit.

In one of these cantinas Lobo encounters “the King,” a Mexican drug lord. Lobo is instantly smitten by the King’s power; or, more precisely, by the aesthetics of power that attend the King. Lobo sees himself as a reader of blood. Indeed, he’s survived the streets by

…learning blood. He could detect its curdle in the parasites who said, Come, come little boy, and invited him into the corner; the way it congealed in the veins of fraidycats who smiled for no reason; the way it turned to water in the bodies of those who played the same heartache on the jukebox, over and over again; the way it dried out like a stone in lowlifes just aching to throw down.

Lobo believes he detects magic in the King’s blood, and vows to become a retainer in the King’s Court, which in time he does. There, in the Palace, he takes up a new mantle. He becomes “the Artist,” a singer of narcorridos he composes to flatter his patron, the King. In the Court,

The Artist realized that people saw him only when he sang or they wanted to hear how tough they were; and that was good, because it meant he could see how things worked in the court.

The Artist’s personality is quickly subsumed into this archetypal Court, which includes the Manager, the Journalist, the Jeweler, the Doctor, the Girl, and the Heir. There’s also the Witch and the Commoner, agents who bring the plot of Kingdom Cons to its climax. There’s a cinematic, page-burner quality to the plot, a briskness that perhaps disguises the novella’s heavier themes of art and power.

Herrera weaves these themes into their own subtle climax. The Artist is initially spellbound by the King, whose very “smile seemed a protective embrace” to the singer. The narcobaron urges the Artist to tell the truth in his corridos, even if the truth is brutal: “Let them be scared, let the decent take offense. Put them to shame. Why else be an artist?” And yet in time the Artist begins to parse the layers of distinction to “truth,” and to see the complicated relationship between truth, beauty, and power. He grows into a new art, a new blood.

Indeed, Kingdom Cons is a subtle, spare Künstlerroman, in which Herrera’s hero’s quiet, internal observations lead him to a new artistic outlook. Regarding a slain narco’s corpse, the Artist thinks first that the man probably deserved his death, before appending the notion: “if there’s one thing we deserve, it’s a heaven that’s real.” When the Artist recognizes himself in a “an ashen boy coaxing squalid notes from a trumpet,” he laments “It’s as if there is no right to beauty.” The Artist seeks to create a right to beauty, to secure a heaven that’s real, but his tools are limited—and thoroughly mediated in violence, in blood. Herrera pushes his hero “to feel the power of an order different from that of the Court,” a power that emanates from “his own sovereign texture and volume. A separate reality.” Herrera’s skill as a writer evokes that “separate reality,” first by creating a mythical-brutal narcoland noir, and then by evoking the consciousness of an artist trying to navigate that violence and find his own power through art, through words.

In its finest moments—of which there are many—Herrera evokes his hero’s consciousness in action. Consider the following passage. The Artist has sneaked out of the Palace to return “to the cantina where he’d first met the King”; there, he observes again, becomes eyes and ears that will channel grimy reality into artful storytelling:

…he heard the fortunes and tragedies of the average jack:

The wetback who’d been deported by immigration and was unwanted on this side as well. They’d told him to sing the anthem, explain what a molcajete was and recite the ingredients of pipián to see if he was really allowed to stay; his jitters made him forget it all so they kicked him out too. The narco-in-training who sent bindles of smack over the river with a slingshot and then simply crossed over to pick them up, until one day he got a wild hair and hit a gringo in the head with his whiterock crackshot, and tho that was the end of his business, he still got a kick out of calling himself an avenger. The woman who, to free herself of her cheating husband, sold the house to a much-feared loanshark and left hubby with no house, no wife, and no peace. The boy who faked his own kidnapping to wheedle money from his parents, who believed the ransom note was real and replied, You know what? We’re tired of that bum, how about bumping him off for half the price? And the boy, out of utter sorrow, said Okay, collected the cash, spent it on booze and then kept his word.

The force of storytelling leads the Artist to an epiphany about the King—and, more significantly, to himself as an artist capable of creating a “separate reality.”

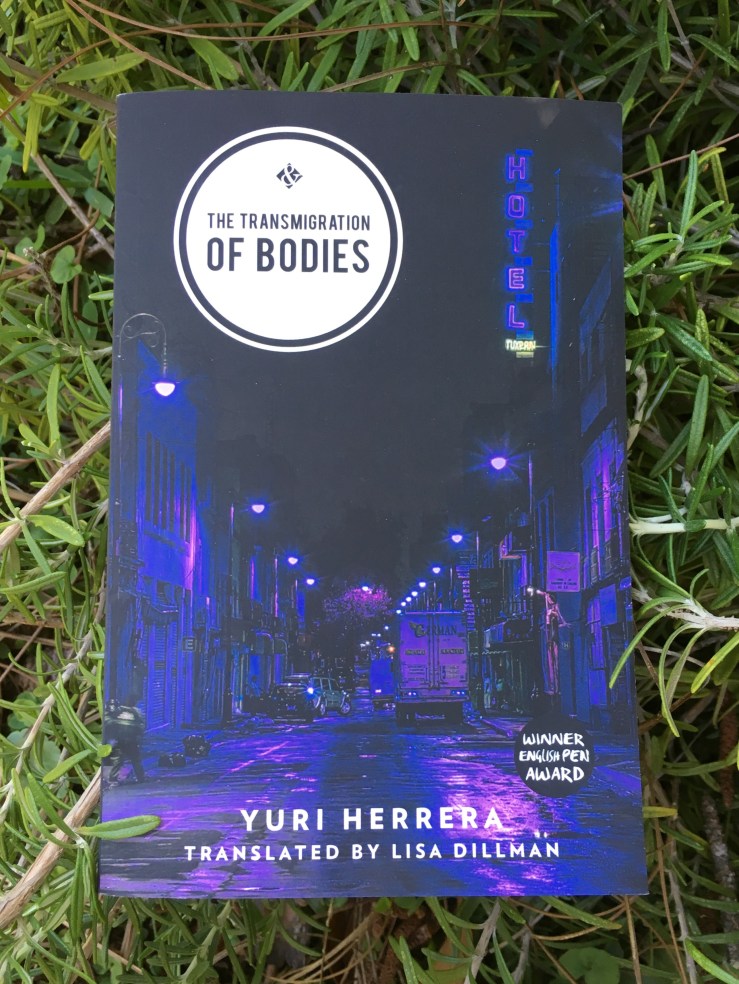

I can’t help but think of Kingdom Cons as the third part of a loose trilogy that also includes Herrera’s previous novellas Signs Preceding the End of the World and The Transmigration of Bodies. All three are published by And Other Stories and all three are translated by Lisa Dillman, who conjures magic in translating Herrera’s neologisms, slang, and mythical tone. Kingdom Cons extends the mythic-noir mode that Signs initiated and Bodies continued. Herrera is a writer with a voice and a viewpoint, an author whose archetypal approach shows the deep significance to contemporary life’s concrete contours. I wrote “trilogy” above, but to be clear, I’d be very happy if Herrera, Dillman, and And Other Stories kept putting out these fine novellas. Highly recommended.

One satirical reading rule for True Detective Season 2 is introduced in the first episode, “The Western Book of the Dead.” In one of

One satirical reading rule for True Detective Season 2 is introduced in the first episode, “The Western Book of the Dead.” In one of  And the plot? What? Another reading rule, indulge me, indulge me, comes in the series’ overuse of aerial shots of L.A. freeways—big converging loops, sometimes black white gray, but often glowing lurid neon at night. The plot is easy to write off as a shaggy dog mess (see also Inherent Vice, Twin Peaks, The Big Lebowski), but it’s not. It does fit together (just like the plots of those examples I proffered parenthetically).

And the plot? What? Another reading rule, indulge me, indulge me, comes in the series’ overuse of aerial shots of L.A. freeways—big converging loops, sometimes black white gray, but often glowing lurid neon at night. The plot is easy to write off as a shaggy dog mess (see also Inherent Vice, Twin Peaks, The Big Lebowski), but it’s not. It does fit together (just like the plots of those examples I proffered parenthetically).

Online auctions allow book-lovers to engage in what could be labeled “biblio-sharking.” Some poor sap needs to clear out his basement to make room for a foosball table or a Jacuzzi, and readers take his books for an extraordinary profit. While the seller may hesitate to dispose of their treasures, I’ll readily pay negligible sums to compensate him for his losses. So, if your rumpus room means more to you than fiction, please please please place your ads on Ebay.

Online auctions allow book-lovers to engage in what could be labeled “biblio-sharking.” Some poor sap needs to clear out his basement to make room for a foosball table or a Jacuzzi, and readers take his books for an extraordinary profit. While the seller may hesitate to dispose of their treasures, I’ll readily pay negligible sums to compensate him for his losses. So, if your rumpus room means more to you than fiction, please please please place your ads on Ebay. Spillane sold hundreds of millions of detective and spy stories during a long career, and the Hammer stories guaranteed him an interested and rabid following. Although private dick Mike Hammer finds himself in any number of slippery situations, Spillane’s central character, rather than any individual plot twist, is what makes these stories both convincing and compelling.

Spillane sold hundreds of millions of detective and spy stories during a long career, and the Hammer stories guaranteed him an interested and rabid following. Although private dick Mike Hammer finds himself in any number of slippery situations, Spillane’s central character, rather than any individual plot twist, is what makes these stories both convincing and compelling. This was the first collection of detective stories I’ve ever finished, and each page dragged me further into a black and white world filled with villains, vixens, and corrupt politicians. The reader becomes an unpaid extra in a B-level film noir.

This was the first collection of detective stories I’ve ever finished, and each page dragged me further into a black and white world filled with villains, vixens, and corrupt politicians. The reader becomes an unpaid extra in a B-level film noir. Michael Wiley is a mystery writer and professor of British Romantic literature and culture at the University of North Florida. He’s published academic volumes about geography and migration in Romantic literature, but we spoke to him about the latest edition in his detective series, The Bad Kitty Lounge. Dr. Wiley was kind enough to talk to us via email about ambiguity and resolution in mystery fiction, giving readers what they want, and the prospects of Wordsworth with a Glock. The Bad Kitty Lounge is available new in hardcover from

Michael Wiley is a mystery writer and professor of British Romantic literature and culture at the University of North Florida. He’s published academic volumes about geography and migration in Romantic literature, but we spoke to him about the latest edition in his detective series, The Bad Kitty Lounge. Dr. Wiley was kind enough to talk to us via email about ambiguity and resolution in mystery fiction, giving readers what they want, and the prospects of Wordsworth with a Glock. The Bad Kitty Lounge is available new in hardcover from

Denis Johnson’s Nobody Move is a tight snare drum of a comedy crime novel. Jimmy Luntz, still decked out in his white barbershop chorus tux (don’t ask) gets into trouble with a big gorilla he owns money too. On the run, he meets smoldering bombshell Anita. More trouble ensues. Nobody Move, originally serialized in Playboy, is a dark, funny genre exercise propelled by Johnson’s sharp dialogue and keen eye for detail. Johnson’s restraint and economy demonstrate writerly chops, but its his story and his characters that made me stay up too late reading last night.

Denis Johnson’s Nobody Move is a tight snare drum of a comedy crime novel. Jimmy Luntz, still decked out in his white barbershop chorus tux (don’t ask) gets into trouble with a big gorilla he owns money too. On the run, he meets smoldering bombshell Anita. More trouble ensues. Nobody Move, originally serialized in Playboy, is a dark, funny genre exercise propelled by Johnson’s sharp dialogue and keen eye for detail. Johnson’s restraint and economy demonstrate writerly chops, but its his story and his characters that made me stay up too late reading last night. I’m kind of embarrassed that I’d never heard of George V. Higgins’s seminal crime novel, The Friends of Eddie Coyle, the story of a down-on-his luck gunrunner trying to get a break on a three-year sentence. Picador’s new edition celebrates the book’s 40th anniversary. Higgins’s electric dialogue thrusts the reader right into the action, trading narrative clarity for a smoky milieu of backroom deals and gritty alleys. But my phrasing here sounds way too corny and trite. Forgive me, I don’t really know how to write about good crime fiction because I’m so unused to it. I’ll lazily favorably compare The Friends of Eddie Coyle to David Simon’s Baltimore crime epic The Wire.

I’m kind of embarrassed that I’d never heard of George V. Higgins’s seminal crime novel, The Friends of Eddie Coyle, the story of a down-on-his luck gunrunner trying to get a break on a three-year sentence. Picador’s new edition celebrates the book’s 40th anniversary. Higgins’s electric dialogue thrusts the reader right into the action, trading narrative clarity for a smoky milieu of backroom deals and gritty alleys. But my phrasing here sounds way too corny and trite. Forgive me, I don’t really know how to write about good crime fiction because I’m so unused to it. I’ll lazily favorably compare The Friends of Eddie Coyle to David Simon’s Baltimore crime epic The Wire. I’ve been too engrossed with Coyle and Nobody Move the past few days to do more than skim over Clancy Martin’s How to Sell, a novel about grifters and scam artists in the jewelery world, but I did read and very much enjoy its first chapter, where the protagonist pawns his mother’s wedding ring (“the only precious thing she had left”) and yet still manages to keep reader sympathy (mine, at least). Martin worked for years in the fine jewelery business. He also translates Nietzsche and Kierkegaard. Zadie Smith says of How to Sell: “It’s a little like Dennis Cooper with a philosophical intelligence, or Raymond Carver without hope. But mostly it’s like itself.” I like that.

I’ve been too engrossed with Coyle and Nobody Move the past few days to do more than skim over Clancy Martin’s How to Sell, a novel about grifters and scam artists in the jewelery world, but I did read and very much enjoy its first chapter, where the protagonist pawns his mother’s wedding ring (“the only precious thing she had left”) and yet still manages to keep reader sympathy (mine, at least). Martin worked for years in the fine jewelery business. He also translates Nietzsche and Kierkegaard. Zadie Smith says of How to Sell: “It’s a little like Dennis Cooper with a philosophical intelligence, or Raymond Carver without hope. But mostly it’s like itself.” I like that.