Disney’s Fantasia is one of the better film adaptations of Thomas Pynchon’s novel Gravity’s Rainbow.

At least this thought zipped into my head a few weeks back, as I watched the film with my wife and kids. I was in the middle of a second reading of the novel, an immediate rereading prompted by the first reading. It looped me back in. Everything seemed connected to the novel in some way. Or rather, the novel seemed to connect itself to everything, through its reader—me—performing a strange dialectic of paranoia/anti-paranoia.

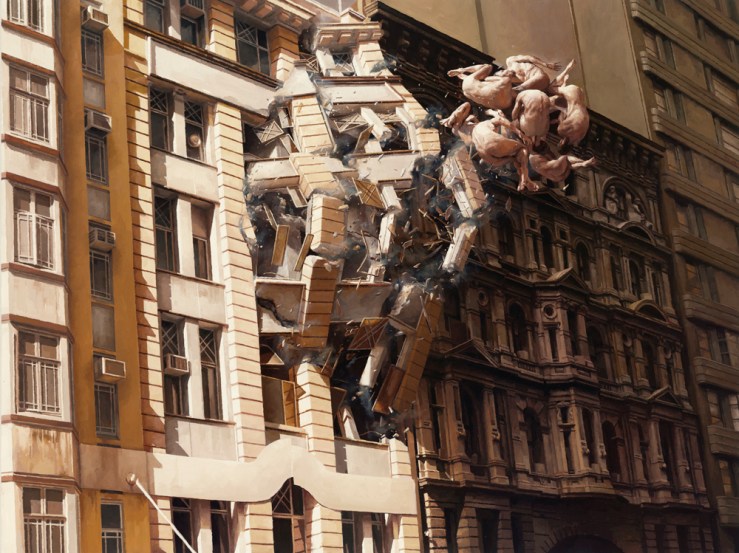

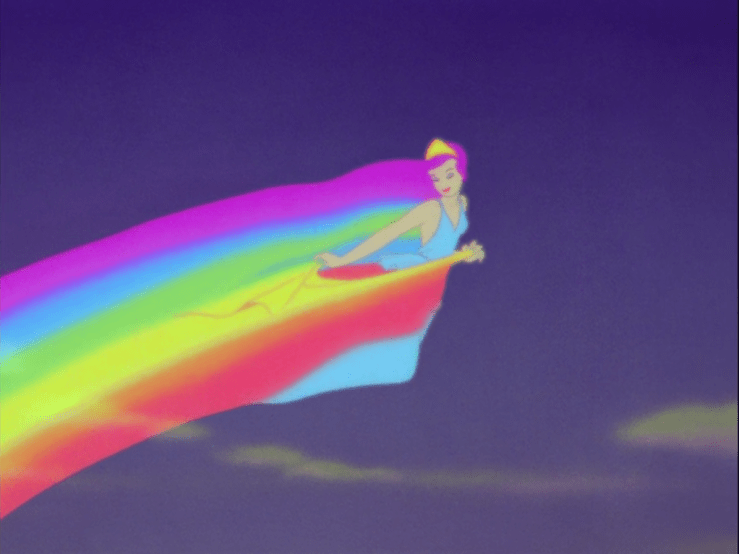

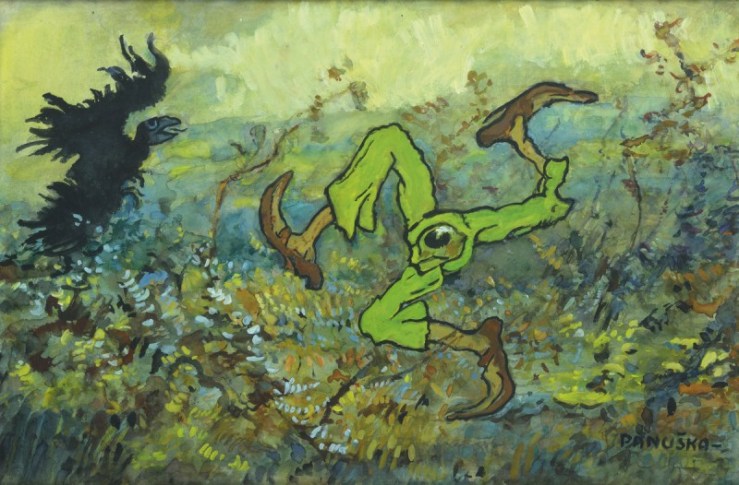

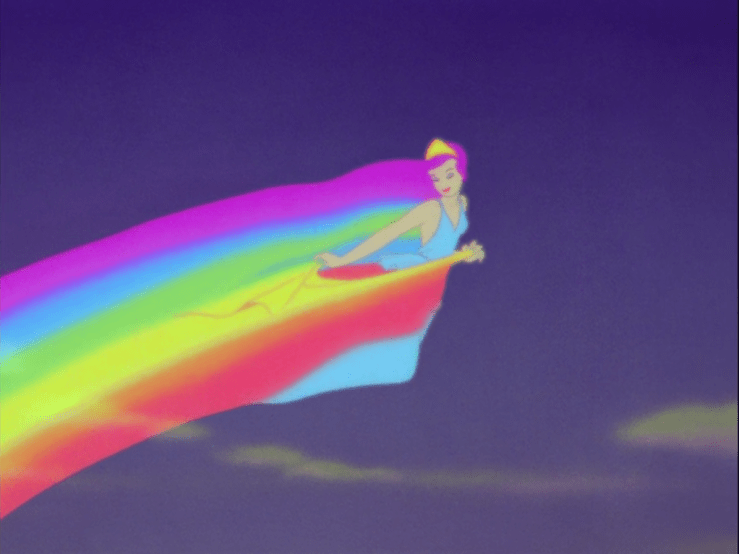

So anyway, Fantasia seemed to me an adaptation of Gravity’s Rainbow, bearing so many of the novel’s features: technical prowess, an episodic and discontinuous form, hallucinatory dazzle, shifts between “high” and “low” culture, parodic and satirical gestures that ultimately invoke sincerity, heightened musicality, themes of magic and science, themes of automation and autonomy, depictions of splintering identity, apocalypse and genesis, cartoon elasticity, mixed modes, terror, love, the sublime, etc.

(There’s even a coded orgy in Fantasia).

But Fantasia was first released in 1940 right, when Pynchon was, what, three or four? And Gravity’s Rainbow was published in 1973, and most of the events in that novel happen at the end of World War II, in like, 1944, 1945, right? So the claim that “Fantasia is one of the better film adaptations of Gravity’s Rainbow” is ridiculous, right?

(Unless, perhaps, we employ those literary terms that Steven Weisenburger uses repeatedly in his Companion to Gravity’s Rainbow: analepsis and prolepsis—so, okay, so perhaps we consider Fantasia an analepsis, a flashback, of Gravity’s Rainbow, or we consider Gravity’s Rainbow a prolepsis, a flashforward, of Fantasia…no? Why not?).

Also ridiculous in the claim that “Fantasia is one of the better film adaptations of Gravity’s Rainbow” is that modifier “better,” for what other film adaptations of Gravity’s Rainbow exist?

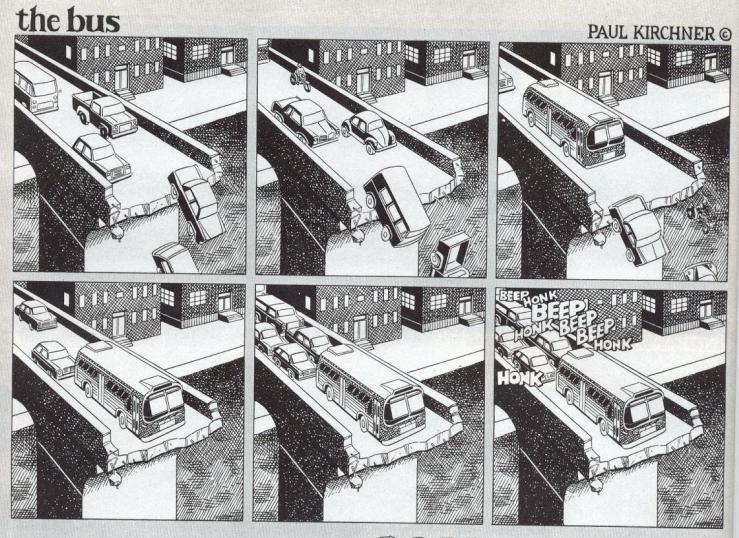

(The list is long and mostly features unintentional titles, but let me lump in much of Robert Altman, The Conversation, Richard Kelly’s Southland Tales, Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master, that Scientology documentary Going Clear, a good bit of stuff by the Wachowksis, The Fisher King (hell, all of Terry Gilliam, why not?), the Blackadder series, which engenders all sorts of wonderful problems of analepsis and prolepsis…).

Gravity’s Rainbow is of course larded with film references, from King Kong and monster movies to German expressionism (Fritz Lang in particular), and features filmmakers and actors as characters. The novel also formulates itself as its own film adaptation, perhaps. The book’s fourth sentence tells us “…it’s all theatre.” (That phrase appears again near the novel’s conclusion, in what I take to be a key passage). And the book ends, proleptically, in “the Orpheus Theatre on Melrose,” a theater managed by Richard M. Nixon, excuse me, Zhlubb—with the rocket analeptically erupting from the past into “The screen…a dim page spread before us, white and silent.” Indeed, as so many of the book’s commentator’s have noted, Pynchon marks separations in the book’s sequences with squares reminiscent of film sprockets — □ □ □ □ □ □ □. Continue reading “A last riff (for now) on Gravity’s Rainbow (and Disney’s Fantasia)” →