“Bitterness for Three Sleepwalkers”

by

Gabriel García Márquez

translated by Gregory Rabassa

Now we had her there, abandoned in a corner of the house. Someone told us, before we brought her things – her clothes which smelled of newly cut wood, her weightless shoes for the mud – that she would be unable to get used to that slow life, with no sweet tastes, no attraction except that harsh, wattled solitude, always pressing on her back. Someone told us – and a lot of time had passed before we remembered it – that she had also had a childhood. Maybe we didn’t believe it then. But now, seeing her sitting in the corner with her frightened eyes and a finger placed on her lips, maybe we accepted the fact that she’d had a childhood once, that once she’d had a touch that was sensitive to the anticipatory coolness of the rain, and that she always carried an unexpected shadow in profile to her body.

All this – and much more – we believed that afternoon when we realized that above her fearsome subworld she was completely human. We found it out suddenly, as if a glass had been broken inside, when she began to give off anguished shouts; she began to call each one of us by name, speaking amidst tears until we sat down beside her; we began to sing and clap hands as if our shouting could put the scattered pieces of glass back together. Only then were we able to believe that at one time she had had a childhood. It was as if her shouts were like a revelation somehow; as if they had a lot of remembered tree and deep river about them. When she got up, she leaned over a little and, still without covering her face with her apron, still without blowing her nose, and still with tears, she told us:

‘I’ll never smile again.’

We went out into the courtyard, the three of us, not talking: maybe we thought we carried common thoughts. Maybe we thought it would be best not to turn on the lights in the house. She wanted to be alone – maybe – sitting in the dark corner, weaving the final braid which seemed to be the only thing that would survive her passage toward the beast.

Outside, in the courtyard, sunk in the deep vapor of the insects, we sat down to think about her. We’d done it so many times before. We might have said that we were doing what we’d been doing every day of our lives.

Yet it was different that night: she’d said that she would never smile again, and we, who knew her so well, were certain that the nightmare had become the truth. Sitting in a triangle, we imagined her there inside, abstract, incapacitated, unable even to hear the innumerable clocks that measured the marked and minute rhythm with which she was changing into dust. ‘If we only had the courage at least to wish for her death,’ we thought in a chorus. But we wanted her like that: ugly and glacial, like a mean contribution to our hidden defects.

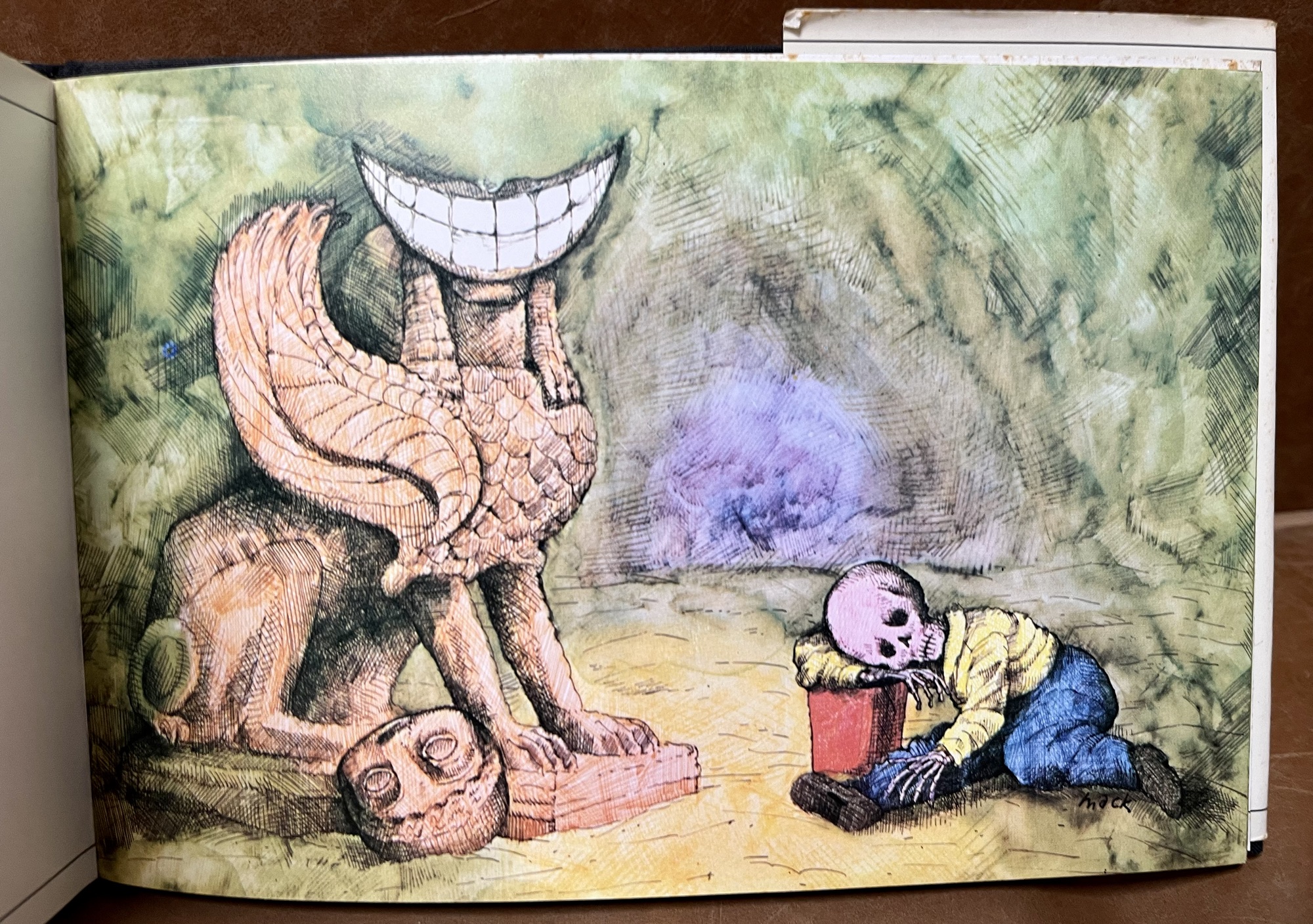

We’d been adults since before, since a long time back. She, however, was the oldest in the house. That same night she had been able to be there, sitting with us, feeling the measured throbbing of the stars, surrounded by healthy sons. She would have been the respectable lady of the house if she had been the wife of a solid citizen or the concubine of a punctual man. But she became accustomed to living in only one dimension, like a straight line, perhaps because her vices or her virtues could not be seen in profile. We’d known that for many years now. We weren’t even surprised one morning, after getting up, when we found her face down in the courtyard, biting the earth in a hard, ecstatic way. Then she smiled, looked at us again; she had fallen out of the second-story window onto the hard clay of the courtyard and had remained there, stiff and concrete, face down on the damp clay. But later we learned that the only thing she had kept intact was her fear of distances, a natural fright upon facing space. We lifted her up by the shoulders. She wasn’t as hard as she had seemed to us at first. On the contrary, her organs were loose, detached from her will, like a lukewarm corpse that hadn’t begun to stiffen.

Her eyes were open, her mouth was dirty with that earth that already must have had a taste of sepulchral sediment for her when we turned her face up to the sun, and it was as if we had placed her in front of a mirror. She looked at us all with a dull, sexless expression that gave us – holding her in my arms now – the measure of her absence. Someone told us she was dead; and afterward she remained smiling with that cold and quiet smile that she wore at night when she moved about the house awake. She said she didn’t know how she got to the courtyard. She said that she’d felt quite warm, that she’d been listening to a cricket, penetrating, sharp, which seemed – so she said – about to knock down the wall of her room, and that she had set herself to remembering Sunday’s prayers, with her cheek tight against the cement floor.

We knew, however, that she couldn’t remember any prayer, for we discovered later that she’d lost the notion of time when she said she’d fallen asleep holding up the inside of the wall that the cricket was pushing on from outside and that she was fast asleep when someone, taking her by the shoulders, moved the wall aside and laid her down with her face to the sun.

That night we knew, sitting in the courtyard, that she would never smile again. Perhaps her inexpressive seriousness pained us in anticipation, her dark and willful living in a corner. It pained us deeply, as we were pained the day we saw her sit down in the corner where she was now; and we heard her say that she wasn’t going to wander through the house any more. At first we couldn’t believe her. We’d seen her for months on end going through the rooms at all hours, her head hard and her shoulders drooping, never stopping, never growing tired. At night we would hear her thick body noise moving between two darknesses, and we would lie awake in bed many times hearing her stealthy walking, following her all through the house with our ears. Once she told us that she had seen the cricket inside the mirror glass, sunken, submerged in the solid transparency, and that it had crossed through the glass surface to reach her. We really didn’t know what she was trying to tell us, but we could all see that her clothes were wet, sticking to her body, as if she had just come out of a cistern. Without trying to explain the phenomenon, we decided to do away with the insects in the house: destroy the objects that obsessed her.

We had the walls cleaned; we ordered them to chop down the plants in the courtyard and it was as if we had cleansed the silence of the night of bits of trash. But we no longer heard her walking, nor did we hear her talking about crickets any more, until the day when, after the last meal, she remained looking at us, she sat down on the cement floor, still looking at us, and said: ‘I’m going to stay here, sitting down,’ and we shuddered, because we could see that she had begun to look like something already almost completely like death.

That had been a long time ago and we had even grown used to seeing her there, sitting, her braid always half wound, as if she had become dissolved in her solitude and, even though she was there to be seen, had lost her natural faculty of being present. That’s why we now knew that she would never smile again; because she had said so in the same convinced and certain way in which she had told us once that she would never walk again. It was as if we were certain that she would tell us later: ‘I’ll never see again,’ or maybe ‘I’ll never hear again,’ and we knew that she was sufficiently human to go along willing the elimination of her vital functions and that spontaneously she would go about ending herself, sense by sense, until one day we would find her leaning against the wall, as if she had fallen asleep for the first time in her life. Perhaps there was still a lot of time left for that, but the three of us, sitting in the courtyard, would have liked to hear her sharp and sudden broken-glass weeping that night, at least to give us the illusion that a baby … a girl baby had been born in the house. In order to believe that she had been born renewed.