Describing Geometry in the Dust is a challenge. I’ve deleted so many openings now and my frustration is mounting: so some very basic description:

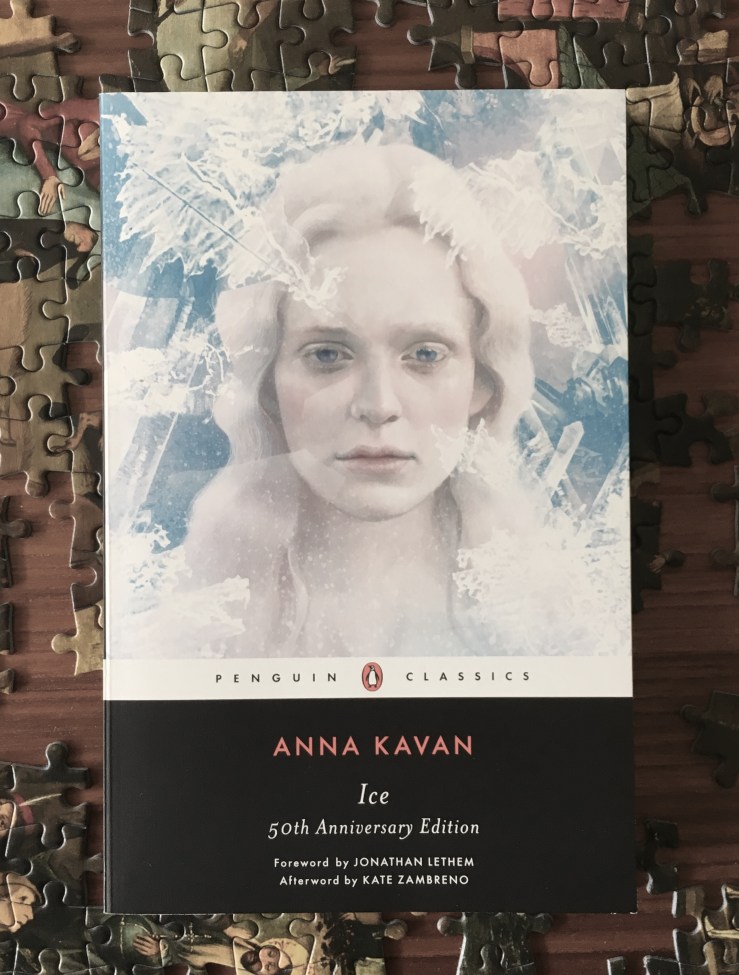

Geometry in the Dust is a novel by the French author Pierre Senges with accompanying illustrations by the Oubapo comix artist Killoffer. The novel was originally published in France (as Géométrie dans la poussière) in 2004. The English translation is by Jacob Siefring, and was published by Inside the Castle earlier this year. Geometry in the Dust is 117 pages and includes 22 black and white illustrations. The prose is set in two columns per page, with infrequent inclusions of inset notes of a smaller font obtruding into the text proper. The typeset is Venetian. The book is approximately 217cm long, 172cm tall, and 10cm thick. It weighs approximately 210 grams.

This is a lousy way to describe a book.

What is it about?, you’ll want to know. What’s the plot? Who are the characters? What’s the drama, the conflict, the themes?, you’ll insist.

So there’s a geometer.

The geometer is a first-person “I” who addresses himself to the “inheriting prince” who rules a “country of sand.” The geometer is of course also addressing himself to you the reader. In addition to being a geometer, he is also

your minister (of Economy, of Religion, of War, and also of the City, we decided). As your sole, faithful minister, your counsellor, chamberlain, and your scapegoat, having weathered many dry seasons and countless reorganizations of your cabinet, I am your confidant too, and, judging from appearances–one can say this without offending the dignity of your kingdom or its constitution, we might even call me your friend.

And so we have our characters: Geometer and his absent audience, his sultan, his reader.

And so for plot? What is our friend, our confidant doing in Geometry in the Dust? He is trying to describe the city that he and his monarch (?) have…dreamed up? Built from scratch? Proposed as a thought experiment?

(I’m not sure.)

The reality or unreality of the city in question should be dispensed with entirely of course. The city is made of words, and it exists in Geometry in the Dust through words. Our narrator implores us in the novel’s second paragraph: “do not be afraid of words!”

So our narrator the geometer tries to describe the city, this city, the sultan’s city, in words. But of course capturing a city in words is a problem—

How does one form an idea of the city, when all one has seen of it are little pieces of it brought back from voyages in trunks? how to describe a metropolis to someone who has only ever known sand and its forms through the cycle of seasons? how to speak of snow to a Moor, of cannibalism to a vegetarian Jesuit?

Measuring a city for our narrator amounts to measuring the angles of waves as they break on the shore: an impossible task. Even metaphors run dry, point in the wrong directions, and ultimately, “all of these measures will be in vain and mediocre , the descriptions will be lost in allegories.” Nevertheless, our narrator will try.

This trying to describe the city is the plot, I suppose, such as it is. And it’s really quite marvelous, far richer and smarter and funnier than I’ve managed to capture here so far. Our geometer is observant, sharp, witty, strangely sincere, flighty and whimsical at times. He advises his prince, his reader, on the value of getting lost in the city (the only way to know it), and a lot of Geometry might amount to our narrator getting lost himself, losing us, leading us in, out, around.

“You will readily understand that a city is not composed only of itself,” he avers at one point, continuing that, “a city is composed of city, the intentions present in the city, and the difference between the city and those intentions…” Perhaps too Geometry is our narrator’s effort to measure the gaps and lacunae between split intentions, and to situate the various players that fill these gaps: black marketeers and insomniacs, calligraphers and macabre dancers, crowders and loners, musicians and animals (including “an alligator of the White Nile” to reside “in the conduits of our main sewer,” whose presence will surely “spice up the lives of your people, those incorrigible auditors of fables.” And if such an alligator can’t be find, never mind–just spread its legends. Words).

And themes?, you ask after. I don’t know. I’ve read Geometry twice now and it’s thick with themes, the basic one, I suppose (and I could be wrong) is: What is a city? (This is too easy, I know). Senges’ narrator invokes and evokes every manner of archaic text, imagined or otherwise; he considers our native tendencies, the roles outsiders play, the movements of crowds, what constitutes a garden, and so forth.

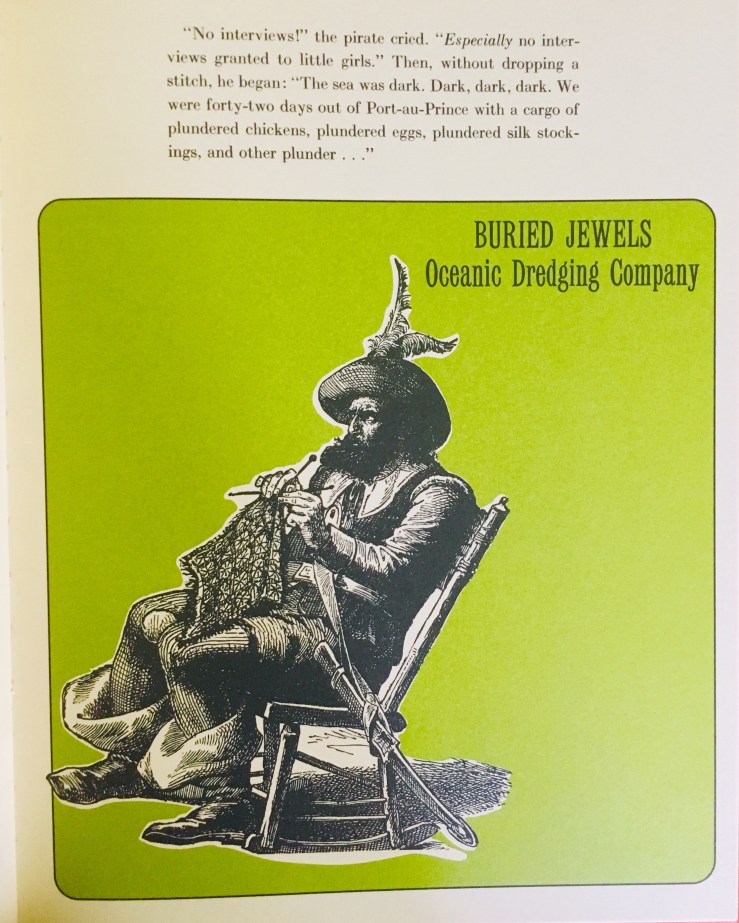

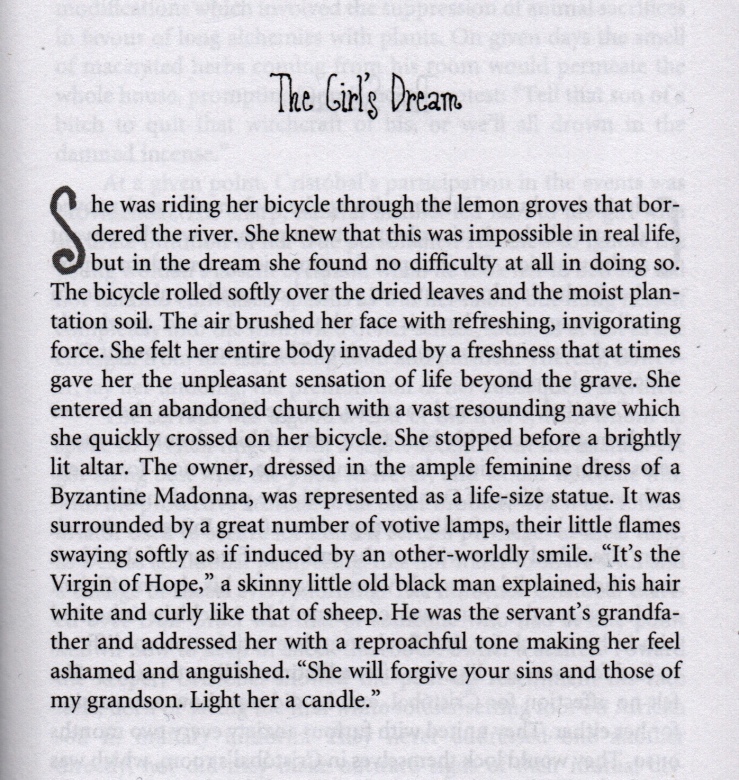

Maybe a better description of Geometry is to simply look at the text itself. Here is a short chapter (go on, read it—click on it if you need a bigger version):

Notice the punctuation: the semicolons, the dashes (em and en), the periods, the parentheses, the commas. Senges’ prose in Geometry is syntactically thick. Sentences, like alleys in a strange city, begin in one place and end up somewhere quite different. The interposition of jostling clauses might cause a reader to lose the subject, to drop the thread or diverge from the path (or pick your metaphor). The effect is sometimes profound, with our narrator arriving at some strange philosophical insight after piling clause upon clause that connects the original subject with something utterly outlandish. And sometimes, the effect is bathetic. In one such example, the narrator, instructing his sovereign on the proper modes of religious observance in the city, moves from a description of the ideal confessional to an evocation of Limbourg’s hell to the necessity of being able grasp a peanut between two fingers. The comical effect is not so much punctured as understood anew though when Senges’ narrator returns to the peanut as a central metaphor for the scope of a city (“there are roughly as many men in the city as peanuts in the city’s bowls”), a metaphor that he extends in clause after clause leading to an invocation of “Hop o’ my Thumb’s pebbles,” a reference to Charles Perrault fairy tale about a boy who uses riverstones to find his way home after having been abandoned in the woods by his parents.

What is the path through Geometry in the Dust? The inset notes, as you can see in the image above, also challenge the reader’s eye, as do the twin columns, so rare in contemporary novels.

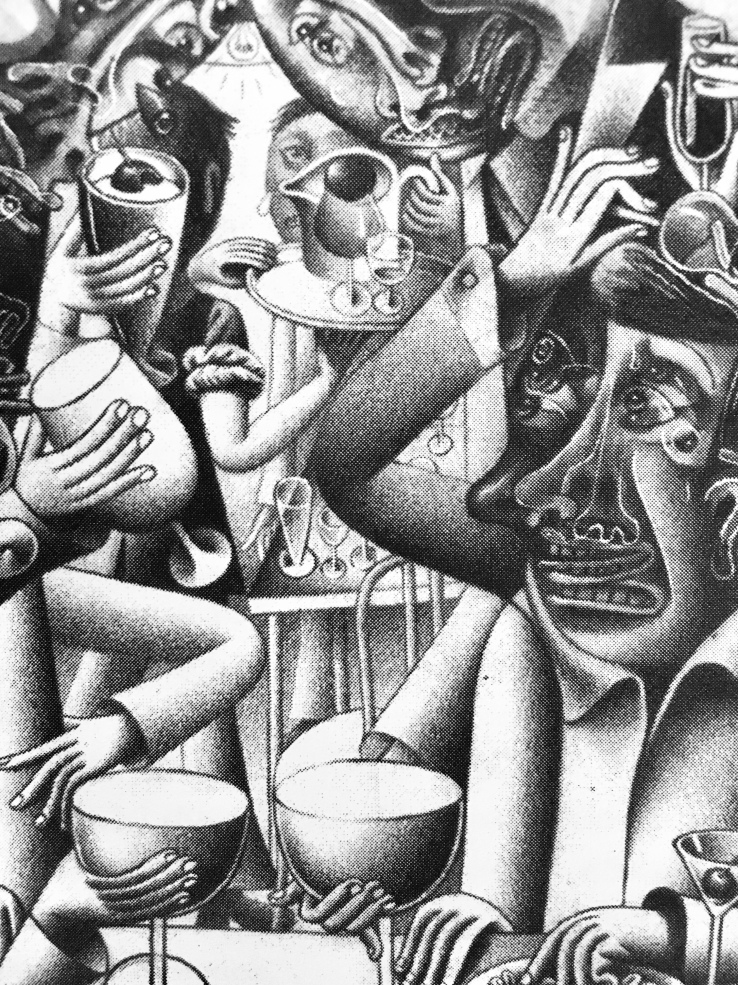

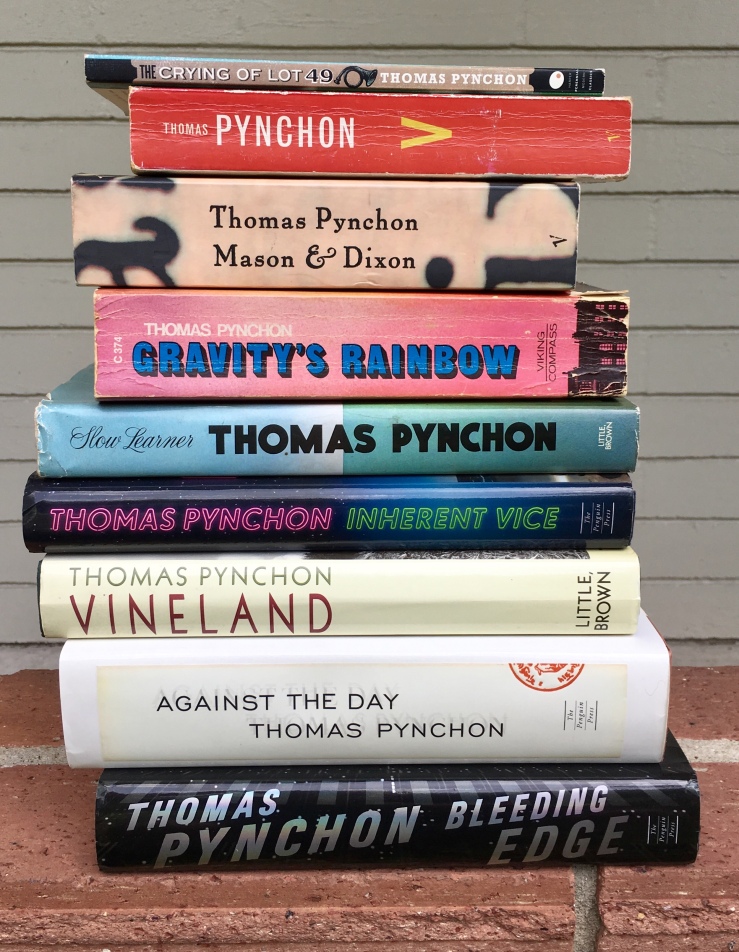

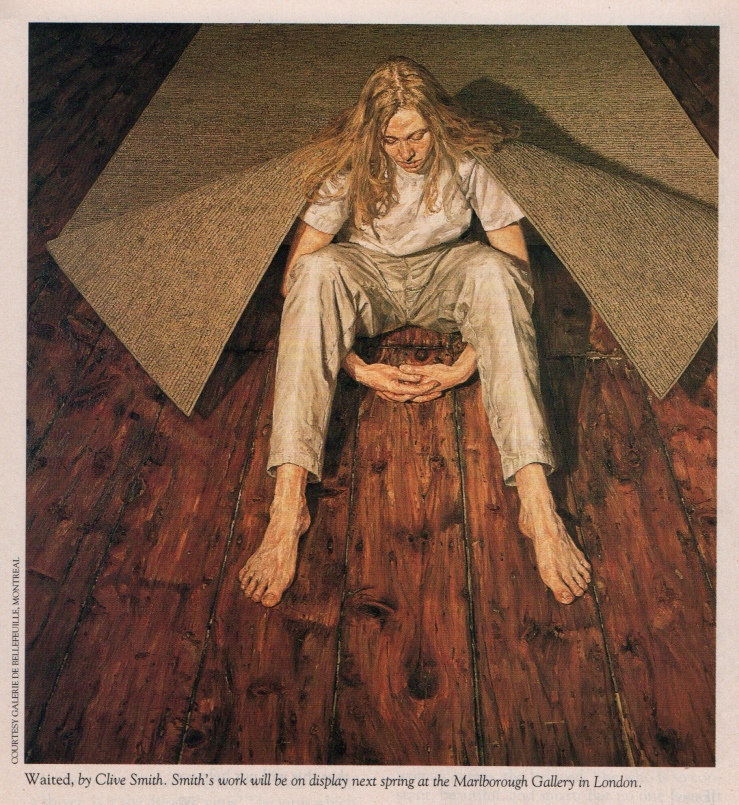

Killoffer’s illustrations also challenge the reader. They do not necessarily correspond in pagination to the sections that they (may) illustrate; rather, they seem to obliquely capture the spirit of the novel. The following image is perhaps the most literal illustration in the novel, evoking something in the passage I shared above:

The experience of reading Geometry is confounding but also rewarding. The first time I read it, at least for the first third or so, I kept looking for all those basic signs of a novel—character, plot, clear conflict, etc. I was happy to find instead something else, something more challenging, but also something unexpectedly fun and funny. In its finest moments, Geometry evokes the essays that Borges disguised as short stories. Readers familiar with Italo Calvino and Georges Perec will find familiar notes here too, as well as those who love the absurd tangles Donald Barthelme’s sentences can take. But Senges is singular here, his own weird flavor, a flavor I enjoyed very much. Recommended.