Ann Quin’s third novel Passages (1969) ostensibly tells the story of an unnamed woman and unnamed man traveling through an unnamed country in search of the woman’s brother, who may or may not be dead.

The adverb ostensibly is necessary in the previous sentence, because Passages does not actually tell that story—or it rather tells that story only glancingly, obliquely, and incompletely. Nevertheless, that is the apparent “plot” of Passages.

Quin is more interested in fractured/fracturing voices here. Passages pushes against the strictures of the traditional novel, eschewing character and plot development in favor of pure (and polluted) perceptions. There’s something schizophrenic about the voices in Passages. Interior monologues turn polyglossic or implode into elliptical fragments.

Quin repeatedly refuses to let her readers know where they stand. Indeed, we’re never quite sure of even the novel’s setting, which seems to be somewhere in the Mediterranean. It’s full of light and sea and sand and poverty, and the “political situation” is grim. (The woman’s brother’s disappearance may or may not have something to do with the region’s political instability.)

Passage’s content might be too slippery to stick to any traditional frame, but Quin employs a rhetorical conceit that teaches her reader how to read her novel. The book breaks into four unnamed chapters, each around twenty-five pages long. The first and third chapters find us loose in the woman’s stream of consciousness. The second and fourth chapters take the form of the man’s personal journal. These sections contain marginal annotations, which might be meant to represent actual physical annotations, or perhaps mental annotations–the man’s stream of consciousness while he rereads his journal.

Quin’s rhetorical strategy pays off, particularly in the book’s Sadean climax. This (literal) climax occurs at a carnivalesque party in a strange mansion on a small island. We see the events first through the woman’s perception, and then through the man’s. But I’ve gone too long without offering any representative language. Here’s a passage from the woman’s section, just a few paragraphs before the climax. To set the stage a bit, simply know that the woman plays voyeur to a bizarre threesome:

Mirrors faced each other. As the two turned, approached. Slower in movement in the centre, either side of him, turning back in the opposite direction to their first movement. Contours of their shadows indistinct. The first mirror reflected in the second. The second in the first. Images within images. Smaller than the last, one inside the other. She lay on the floor, wrists tied together. She bent back over the chair. He raised the whip, flung into space.

Later, the man’s perception of events at the party both clarify and cloud the woman’s account. As you can see in the excerpt above, the woman frequently refuses to qualify her pronouns in a way that might stabilize identities for her reader. Such obfuscation often happens in the course of a sentence or two:

I ran on, knowing I was being followed. She came to the edge, jumped into expanding blueness, ultra violet tilted as she went towards the beach. We walked in silence.

The woman’s I becomes a She and then merges into a We. The other half of that We is a He, the follower (“He later threw the bottle against the rocks”), but we soon realize that this He is not the male protagonist, but simply another He that the woman has taken as a one-time lover.

The woman frequently takes off somewhere to have sex with another man. At times the sex seems to be part of her quest to find her brother; other times it’s simply part of the novel’s dark, erotic tone. The man is undisturbed by his lover’s faithlessness. He is passive, depressive, and analytical, while she is manic and exuberant. Late in the novel he analyzes himself:

How many hours I waste lying in bed thinking about getting up. I see myself get up, go out, move, drink, eat, smile, turn, pay attention, talk, go up, go down. I am absent from that part, yet participating at the same time. A voyeur in all senses, in my actions, non-actions. What a delight it might be actually to get up without thinking, and then when dressed look back and still see myself curled up fast asleep under the blankets.

The man longs for a kind of split persona, an active agent to walk the world who can also gaze back at himself dormant, passive.

This motif of perception and observation echoes throughout Passages. Consider one of the man’s journal entries from early in the book:

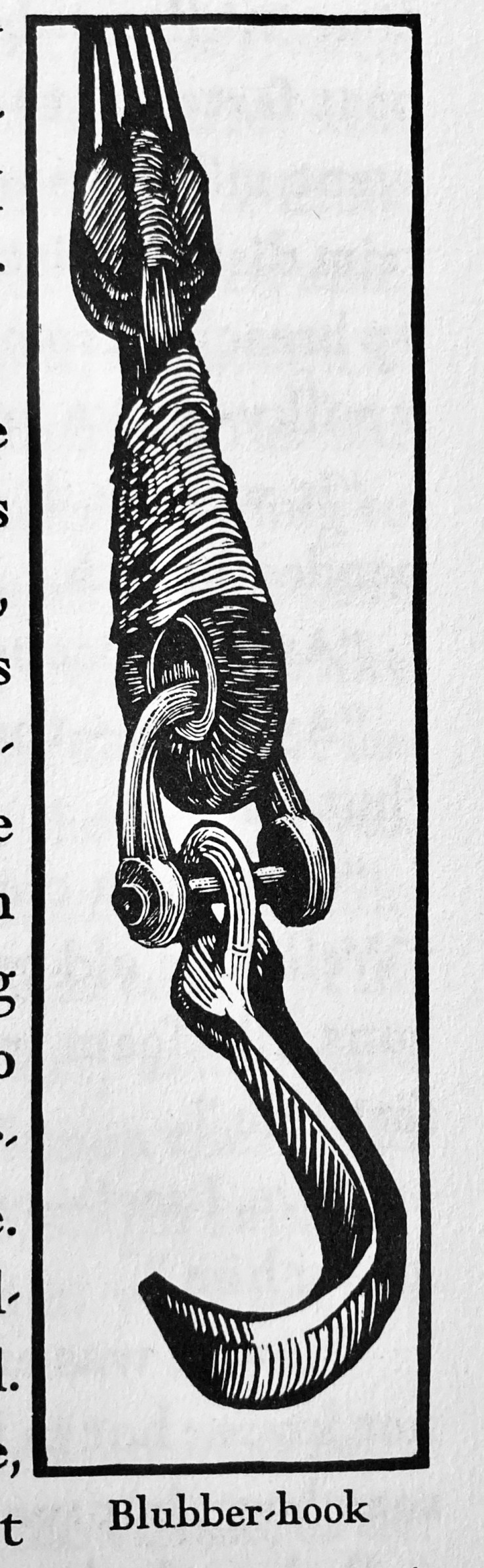

Above, I used an image instead of text to give a sense of what the journal entries and their annotations look like. Here, the man’s annotation is a form of self-observation, self-analysis.

Other annotations dwell on describing myths or artifacts (often Greek or Talmudic). In a “December” entry, the man’s annotation is far lengthier than the text proper. The main entry reads:

I am on the verge of discovering my own demoniac possibilities and because of this I am conscious I am not alone with myself.

Again, we see the fracturing of identity, consciousness as ceaseless self-perception. The annotation is far more colorful in contrast:

An ancient tribe of the Kouretes were sorcerers and magicians. They invented statuary and discovered metals, and they were amphibious and of strange varieties of shape, some like demons, some like men, some like fishes, some like serpents, and some had no hands, some no feet, some had webs between their fingers like gees. They were blue-eyed and black-tailed. They perished struck down by the thunder of Zeus or by the arrows of Apollo.

Quin’s annotations dare her reader to make meaning—to put the fragments together in a way that might satisfy the traditional expectations we bring to a novel. But the meaning is always deferred, always slips away. Passages collapses notions of center and margin. As its title suggests, this is a novel about liminal people, liminal places.

The results are wonderfully frustrating. Passages is abject, even lurid at times, but also rich and even dazzling in moments, particularly in the woman’s chapters, which read like pure perception, untethered by traditional narrative expectations like causation, sequence, and chronology.

As such, Passages will not be every reader’s cup of tea. It lacks the sharp, grotesque humor of Quin’s first novel, Berg, and seems dead set at every angle to confound and even depress its readers. And yet there’s a wild possibility in Passages. In her introduction to the new edition of Passages recently published by And Other Stories, Claire-Louise Bennett tries to capture the feeling of reading Quin’s novel:

It’s difficult to describe — it’s almost like the omnipotent curiosity one burns with as an adolescent — sexual, solipsistic, melancholic, fierce, hungry, languorous — and without limit.

Bennett, whose anti-novel Pond bears the stamp of Quin’s influence, employs the right adjectives here. We could also add disorienting, challenging, abject and even distressing. While clearly influenced by Joyce and Beckett, Quin’s writing in Passages seems closer to William Burroughs’s ventriloquism and the hollowed-out alienation of Anna Kavan’s early work. Passages also points towards the writing of Kathy Acker, Alasdair Gray, and João Gilberto Noll, among others. But it’s ultimately its own weird thing, and half a century after its initial publication it still seems ahead of its time. Passages is clearly Not For Everyone but I loved it. Recommended.