Antoine Volodine’s collection of loosely-connected stories Writers (2010; English translation by Katina Rogers, Dalkey Archive, 2014) is 108 pages. I have read the first four of the seven stories here—the first 54 pages. This is the first book by Volodine that I have read. Antoine Volodine is in fact a pseudonym, I know, but I don’t know much else about the writer. I’ve been meaning to read him for a few years, after some good folks suggested I do so, but I’ve never come across any of his books in the wild until this weekend. After I finish Writers I will read more about Volodine, but for now I am enjoying (?) how and what this book teaches me about the bigger project Volodine seems to be working towards.

That bigger project evinces in the first story in the collection, “Mathias Olbane,” which centers on the titular character, a writer who tries to hypnotize himself into a suicide attempt. Poor Mathias goes to prison for twenty-six years — “He had assassinated assassins.” Like most of the figures in Writers (so far anyway—you see by the title of this post that I am reporting from half way through, yes?) — like most of the figures in Writers, Mathias is a revolutionary spirit, resisting capitalist power and conformist order through radical violence. Before prison, Mathias wrote two books. The first, An Autumn at the Boyols’ “consisted of eight short texts, inspired by fantasy or the bizarre, composed in a lusterless but impeccable style. Let’s say that it was a collection that maintained a certain kinship with post-exoticism…” The description of the book approximates a description of Writers itself; notably, Volodine identifies his own genre as post-exoticism. Autumn at the Boyols’ doesn’t sell at all, and its sequel, Splendor of the Skiff (which “recounted a police investigation, several episodes of a global revolution, and traumatizing incursions into dream worlds”) somehow fares even worse. Mathias begins a new kind of writing in prison:

…after twenty-six years in captivity, he had forged approximately a hundred thousand words, divided as follows:

- sixty thousand first and last names of victims of unhappineess

- twenty thousand names of imaginary plants, mushrooms, and herbs

- ten thousand names of places, rivers, and localities

- and ten thousand various words that do not belong to any language, but have a certain phonetic logic that makes them sound familiar

I love the mix of tones here: Mathias Olbane’s grand work is useless and strange and sad and ultimately unknowable, and Volodine conveys this with both sinister humor and dark pathos. Once released from prison, our hero immediately becomes afflicted with a rare and incurable and painful disease. Hence, the suicide urge. But let’s move on.

The second tale in Writers, “Speech to the Nomads and the Dead,” offers another iteration of post-exotic writing, both in form and content. The story plays out like a weird nightmare. Linda Woo, isolated and going mad in a prison cell, conjures up an audience of burn victims, an obese dead man, Mongolian nomads, and several crows. She delivers a “lesson” to her auditors (a “lesson,” we learn, is one of post-exoticism’s several genres). The lesson is about the post-exotic writers themselves. She names a few of these post-exotic writers (Volodine is addicted to names, especially strange names), and delivers an invective against the modern powers that the post-exotic writers write against:

Post-exoticism’s writers…have in their memory, without exception, the wars and the ethnic and social exterminations that were carried out from one end of the 20th century to the other, they forget none and pardon none, they also keep permanently in mind the savageries and the inequalities that are exacerbated among men…

The above excerpt is a small taste of Woo’s bitter rant, which goes on for long sentence after long sentence (Volodine is addicted to long sentences). Like Mathias Olbane, Linda Woo writes in the face of futility, creating the “post-exotic word,” a word that creates an “absurd magic” that allows the post-exotic writers to “speak the world.”

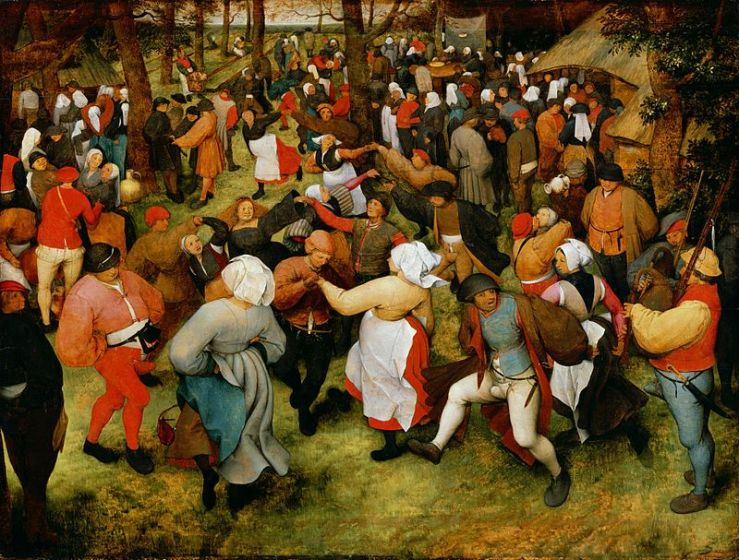

Linda Woo’s name appears in the next story in Writers, “Begin-ing,” if only in passing. This story belongs to an unnamed writer, yet another prisoner. Wheelchair-bound, he is interrogated and tortured by two insane inmates who have taken over their prison, having killed their captors. The pair, Greta and Bruno Khatchatourian, are thoroughly horrific, spouting abject insanities that evoke Hieronymus Boschs’s hell. They are terrifying, and I had a nightmare the night that I read “Begin-ing.” It’s never quite clear if Greta and Bruno Khatchatourian are themselves post-exotic writers gone mad or just violent lunatics on the brink of total breakdown. In any case, Volodine affords them dialogue that veers close to a kind of horror-poetry. “We can also spew out the apocalypse,” Greta defiantly sneers. They torture the poor writer. Why?

They would like it, in the end, if he came around to their side, whether by admitting that he’s been, for a thousand years, a clandestine leader of dark forces, or by tracing for them a strategy that could lead them to final victory. … They would like above all for him to help them to drive the dark forces out from the asylum, to prepare a list of spies, they want him to rid the world of the last nurses, of Martians, of colonialists, and of capitalists in general.

The poor writer these lunatics torture turns inward to his own formative memories of first writings, of begin-ing, when he created his own worlds/words in ungrammatical misspelled scrawlings, filling notebook after notebook. Volodine unspools these memories in sentences that carry on for pages, mostly centering on the writer’s strange childhood in an abject classroom where he engages in depravities that evoke Pasolini’s Salò. And yet these memories are the writer’s comfort—or at least resistance—to the lunatics’ violence. Volodine’s prose in “Begin-ing” conjures Goya’s various lunatics, witches, demons, and dogs. It’s all very upsetting stuff.

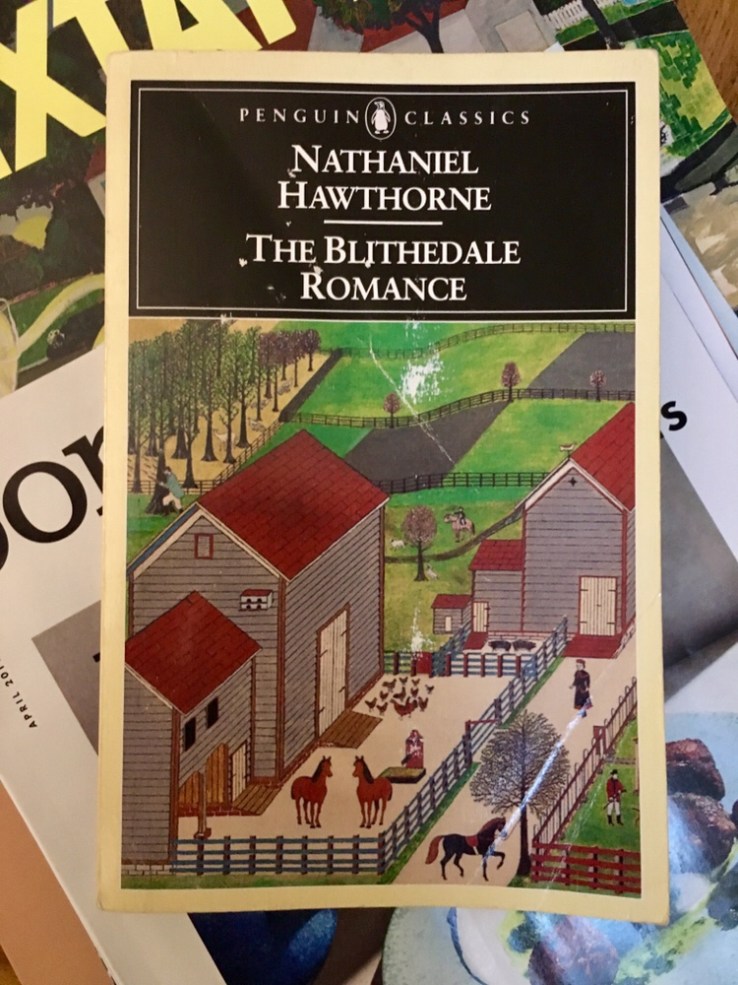

After the depravity of “Begin-ings,” the caustic comedy of the next story “Acknowledgements” is a welcome palate cleanser. In this story’s twelve pages (I wish there were more!) Volodine simultaneously ridicules and exults the “Acknowledgements” page that often appends a novel, elevating the commonplace gesture to its own mock-heroic genre. The story begins with the the hero-writer thanking “Marta and Boris Bielouguine, who plucked me from the swamp that I had unhappily fallen into along with the bag containing my manuscript.” The “swamp” here is not a metaphor, but a literal bog the writer nearly drowned in. And the manuscript? A Meeting at the Boyols’, a title that recalls poor Mathias Olbane’s first book An Autumn at the Boyols’. Each paragraph of “Acknowledgments” is its own vignette, a miniature adventure in the form of a thank-you note to certain parties. Most of the vignettes end in sex or death, or an escape from one of the two. “Grad Litrif and his companion Lioudmila” as well as “the head of the Marbachvili archives” (oh the names in this story!) are thanked for allowing the writer

…to access the notebooks of Vulcain Marbachvili, from which I was able, for my story Long Ago to Bed Early, to copy several sentences before the earthquake struck that engulfed the archives. My thanks to these three people, and apologies to the archivist, as I was sadly unable to locate either her name or her body in the rubble.

“Acknowledgments” is littered with such bodies—sometimes victims of disasters and plagues, and elsewhere the bodies of the married or boyfriended women the writer copulates with before escaping into some new strange circumstances (he often thanks the husbands and the boyfriends, and in one inspired moment, thanks a gardener “who one day had the presence of mind to detain Bernardo Balsamian in the orchard while Grigoria and I showered and got dressed again”). He thanks a couple who shows him their collection of 88 stuffed guinea pigs; he thanks “the leader of the Muslim Bang cell” who, during his “incarceration in Yogyakarta…forbid the prisoners on the floor from sodomizing” him; he thanks the “Happy Days” theater troupe who “had the courage” to perform his play Djann’s Awakening three times “before a rigorously empty room.” Most of the acknowledgments connect the writer’s thank-you to a specific book he’s written. I’m tempted to list them all (oh the names!), but just a few—Tomorrow the Otters, Eve of Pandemic, Journal of Pandemonium, Goodbye Clouds, Goodbye Romeo, Mlatelpopec in Paradise, Macbeth in Paradise, Hell in Paradise…Without exaggeration: “Acknowledgements” is one of the funniest stories I’ve ever read.

With its evocations of mad and obscure writers, Volodine’s books strongly reminds me of Roberto Bolaño’s work. And yet reading it is not like reading an attempt to copy another writer—which Volodine is in no way doing—but rather like reading a writer who has filtered much of the same material of the 20th century through himself, and has come to some of the same tonal and thematic viewpoints—Volodine’s labyrinth is dark and weird and sinister and abject, but also slightly zany and terribly funny. More to come.

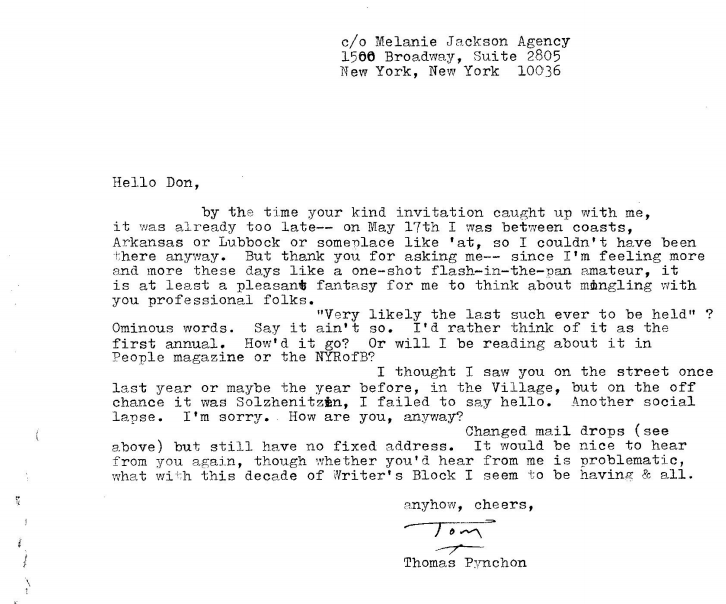

To date, Thomas Ruggles Pynchon (American, b. 1937), has published eight novels and one collection of short stories. These books were published between 1963 and 2013. On this day, Thomas Ruggles Pynchon’s 81st birthday, I present my ranking of his novels. My ranking is completely subjective, essentially incomplete (in that I haven’t read two of Pynchon’s novels all the way through), and thoroughly unnecessary. My ranking should be disregarded, but I do not think it should be treated with any malice. You are most welcome to make your own ranking in the comments section of this post, or perhaps elsewhere online, or on a scrap of your own paper, or in personal remarks to a friend or loved one, etc. I have not included the short story collection Slow Learner (1984) in this ranking because it is not a novel.

To date, Thomas Ruggles Pynchon (American, b. 1937), has published eight novels and one collection of short stories. These books were published between 1963 and 2013. On this day, Thomas Ruggles Pynchon’s 81st birthday, I present my ranking of his novels. My ranking is completely subjective, essentially incomplete (in that I haven’t read two of Pynchon’s novels all the way through), and thoroughly unnecessary. My ranking should be disregarded, but I do not think it should be treated with any malice. You are most welcome to make your own ranking in the comments section of this post, or perhaps elsewhere online, or on a scrap of your own paper, or in personal remarks to a friend or loved one, etc. I have not included the short story collection Slow Learner (1984) in this ranking because it is not a novel.