He had brought with him a dime novel, one of the Chums of Chance series, The Chums of Chance at the Ends of the Earth, and for a while each night he sat in the firelight and read to himself but soon found he was reading out loud to his father’s corpse, like a bedtime story, something to ease Webb’s passage into the dreamland of his death.

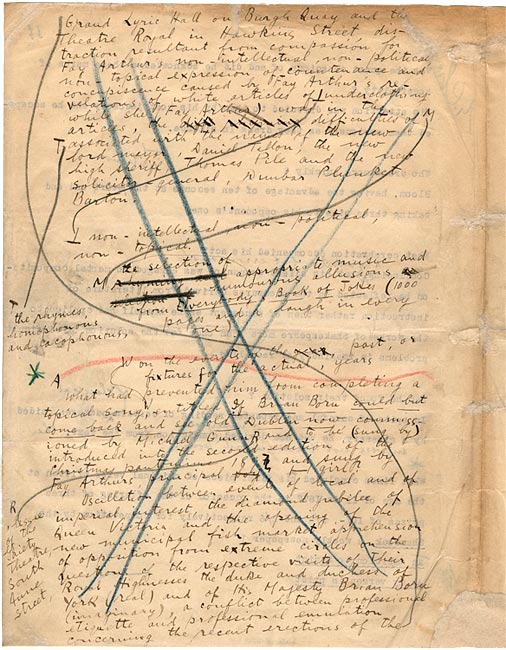

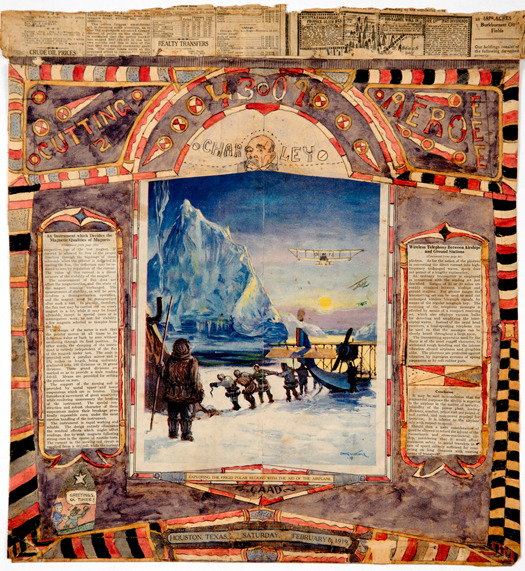

Reef had had the book for years. He’d come across it, already dog-eared, scribbled in, torn and stained from a number of sources, including blood, while languishing in the county lockup at Socorro, New Mexico, on a charge of running a game of chance without a license. The cover showed an athletic young man (it seemed to be the fearless Lindsay Noseworth) hanging off a ballast line of an ascending airship of futuristic design, trading shots with a bestially rendered gang of Eskimos below. Reef began to read, and soon, whatever “soon” meant, became aware that he was reading in the dark, lights-out having occurred sometime, near as he could tell, between the North Cape and Franz Josef Land. As soon as he noticed the absence of light, of course, he could no longer see to read and, reluctantly, having marked his place, turned in for the night without considering any of this too odd. For the next couple of days he enjoyed a sort of dual existence, both in Socorro and at the Pole. Cellmates came and went, the Sheriff looked in from time to time, perplexed.

At odd moments, now, he found himself looking at the sky, as if trying to locate somewhere in it the great airship. As if those boys might be agents of a kind of extrahuman justice, who could shepherd Webb through whatever waited for him, even pass on to Reef wise advice, though he might not always be able to make sense of it. And sometimes in the sky, when the light was funny enough, he thought he saw something familiar. Never lasting more than a couple of watch ticks, but persistent. “It’s them, Pa,” he nodded back over his shoulder. “They’re watching us, all right. And tonight I’ll read you some more of that story. You’ll see.”

Riding out of Cortez in the morning, he checked the high end of the Sleeping Ute and saw cloud on the peak. “Be rainin later in the day, Pa.”

“Is that Reef? Where am I? Reef, I don’t know where the hell I am—”

“Steady, Pa. We’re outside of Cortez, headin up to Telluride, be there pretty soon—”

“No. That’s not where this is. Everthin is unhitched. Nothin stays the same. Somethin has happened to my eyes. . . .”

“It’s O.K.”

“Hell it is.”

—From Thomas Pynchon’s novel Against the Day (215).

1. There’s so much I like about this passage.

2. First, Pynchon explicitly ties together two groups of his characters here. Pynchon connects the Traverses of Colorado with those champions of the ether, The Chums of Chance.

And he does it through a novel, which I’ll get to in a minute.

3. I’ve already remarked on the adventurous, even light-hearted tone of the Chums of Chance episodes, which often buoy the narrative out of its byzantine winding.

4. The Chums passages contrast strongly with the Colorado episodes featuring the Traverses.

While Pynchon is not really known for his pathos or the depth of his characters, the Traverse story line is genuinely moving. We see the family disintegrate against the greed of the Colorado mining rush. Patriarch Webb cannot hold his family together, and he gives over to a deep bitterness; his union becomes his raison d’etre, and he undertakes dangerous secret missions to fight the forces of capitalism. It’s worth giving Webb’s opinion at length:

“Here. The most precious thing I own.” He took his union card from his wallet and showed them, one by one. “These words right here”—pointing to the slogan on the back of the card— “is what it all comes down to, you won’t hear it in school, maybe the Gettysburg Address, Declaration of Independence and so forth, but if you learn nothing else, learn this by heart, what it says here—‘Labor produces all wealth. Wealth belongs to the producer thereof.’ Straight talk. No doubletalking you like the plutes do, ’cause with them what you always have to be listening for is the opposite of what they say. ‘Freedom,’ then’s the time to watch your back in particular—start telling you how free you are, somethin’s up, next thing you know the gates have slammed shut and there’s the Captain givin you them looks. ‘Reform’? More new snouts at the trough. ‘Compassion’ means the population of starving, homeless, and dead is about to take another jump. So forth. Why, you could write a whole foreign phrase book just on what Republicans have to say.”

5. It’s also worth pointing out that Webb is likley the Kieselguhr Kid: He has a secret identity and secret powers, like many of the characters who inhabit Against the Day.

6. The Traverse passages recall the social realism of Steinbeck at times, with a dose of the moralizing we might find in Upton Sinclair. There’s also a heavy dash of Ambrose Bierce’s cynicism, and something of Bret Harte’s milieu here.

A kind of ballast for Pynchon’s flightier whims? Not sure.

7. Returning to our initial citation:

As prodigal son Reef Traverse moves his father’s corpse across Colorado, he reads from The Chums of Chance at the Ends of the Earth. We learn that he’s had the dime novel for years and we learn of its physical condition — “dogeared, scribbled in, torn and stained from a number of sources, including blood.” The book is a kind of abject survivor, a physical totem with powers of endurance, which, in turn, grants metaphysical powers on its user-reader.

8. (Parenthetical (i.e. unexplored) aside: The cover of The Chums of Chance at the Ends of the Earth features handsome, uptight Lindsay Noseworth facing off against a “bestially rendered gang of Eskimos.” Here is our Manifest Destiny; here is our White Man’s Burden).

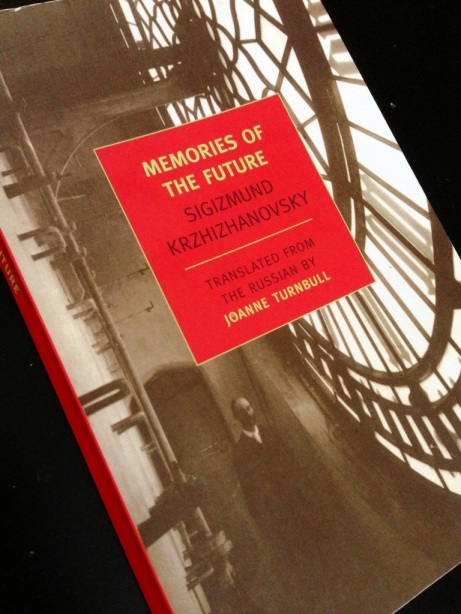

9. The Chums of Chance at the Ends of the Earth allows Reef brief transcendence of time (“whatever ‘soon’ meant”) and space (it provides him escape from his jail cell).

10. Also: The Chums of Chance at the Ends of the Earth grants its reader the power to read in the dark. There is something of a huge in-joke here that all late-night readers will appreciate.

Also: the major motif of At the End of the Day is darkness and light. The Chums of Chance at the Ends of the Earth works as a kind of self-illuminating object outside the confines of the physical world, but only when the user is not conscious of this power (“As soon as he noticed the absence of light, of course, he could no longer see to read”).

11. The Chums of Chance at the Ends of the Earth bestows upon Reef, its operator, “a sort of dual existence, both in Socorro and at the Pole.” This relationship, again, won’t be unfamiliar to voracious readers. Hell, many of us chase that transcendent space the rest of our lives. The older we get, the harder it is to get back to Dickensian London or Rivendell or Crusoe’s island or Narnia or Thornfield Hall or wherever it was that we got to live out part of our dual existence.

Here Reef, a grown-ass man, gets to be one of the Chums and traverse an alien frontier.

12. And the biggie: Somehow this dime novel wakes the dead.

Now, it’s easy to say that Webb doesn’t really talk to Reef, just as we can easily say that Reef doesn’t really head to the pole with the Chums, doesn’t really transcend time and space, etc. We could look for simple answers in psychology—Reef has internalized his father’s voice; Reef is going mad.

But I think Pynchon’s presentation of the scene suggests something more—but something I don’t know how to name or describe, only a fifth of the way into this book. Something to look for in any case.

And so thus end with Webb’s line: “Somethin has happened to my eyes.”