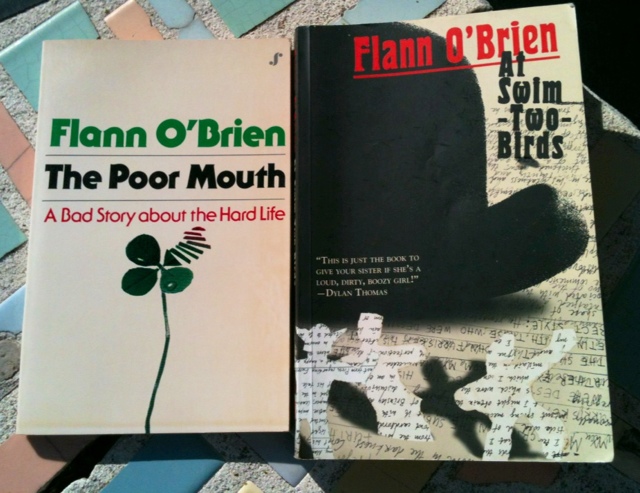

Here’s the short review: Flann O’Brien’s The Third Policeman is a dark, comic masterpiece—witty, bizarre, and buzzing with surreal transformations that push the limits of language. I am ashamed that I came so late to its cult (how the novel escaped my formative teens and twenties escapes me), but also thankful that I trusted the readers of this blog who kindly suggested I read it.

I’m also thankful that I knew pretty much nothing about the book going in; I’m thankful that I skipped over Denis Donoghue’s introduction (which has the gall to spoil the novel’s end); I’m thankful that I resisted looking up information on de Selby, a philosopher I had never heard the name of before The Third Policeman. I read the novel in an ideal state, a kind of Platonic purity of appropriate bewilderment, at turns gaping and guffawing at O’Brien’s sublime impositions on plot, imagery, thought, language.

To be plain, I think that you should read the book too, gentlest reader, and if you are fortunate enough to possess innocence of its strange virtues, all the better. The less you know about The Third Policeman, the more enjoyable your first time will be. But if such conditions are too much to ask, here are a few fragments of plot:

We have an unnamed narrator, a one-legged orphan and would-be de Selby scholar (don’t ask) who enters into a nefarious plot with a man named Divney. Okay, they plan and execute a murder for treasure. Shades of Crime and Punishment creep into the novel by way of Poe’s nervous narrators; the plot even anticipates in some ways The Stranger, though not as moody and far funnier and honestly just way better. (I’m riffing on books here because, again, it seems to me a disservice to the interested reader to overshare the plot of The Third Policeman).

Let’s just say there’s a two-dimensional house. Let’s just say there’s an absurd picaresque quest to recover a missing black box. Let’s just say there are two policemen (okay, there are three), alternately terrifying, edifying, assuaging, bewildering. Let’s just say there’s an army of one-legged men. Let’s just say there’s a soul. Let’s call him “Joe.”

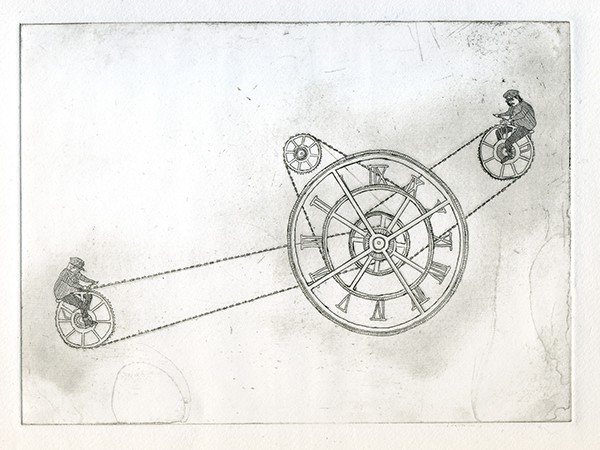

Let’s just say there are bicycles. Lots and lots of bicycles.

And the wisdom (?!) of de Selby, of course, “the savant,” who, via our unnamed narrator’s erudite footnotes (including the notes of de Selby’s esteemed commentators, of course) offers up opinions and maxims on matters of natural science and philosophy alike. Here’s a taste of de Selby, from the epigraph:

Human existence being an hallucination containing in itself the secondary hallucinations of day and night (the latter an insanitary condition of the atmosphere due to accretions of black air) it ill becomes any man of sense to be concerned at the illusory approach of the supreme hallucination known as death.

It’s also a good taste of the bizarre thrust of The Third Policeman; the first five words might work as a dandy summary, or at least summary enough.

But maybe I should share some of O’Brien’s language (and not just some philosopher that if you’re being honest you’ll admit you’ve never heard of before, although it seems like maybe you ought to have heard of him, hmmm?).

Just the first paragraph, gentle soul. It was enough to hook this fish:

Not everybody knows how I killed old Phillip Mathers, smashing his jaw in with my spade; but first it is better to speak of my friendship with John Divney because it was he who first knocked old Mathers down by giving him a great blow in the neck with a special bicycle-pump which he manufactured himself out of a hollow iron bar. Divney was a strong civil man but he was lazy and idle-minded. He was personally responsible for the whole idea in the first place. It was he who told me to bring my spade. He was the one who gave the orders on the occasion and also the explanations when they were called for.

And: two more excerpts that you can read, funny-stuff, context-free.

Okay. Hopefully I’ve convinced you a) to read The Third Policeman and b) to quit reading this review (let’s be honest, this isn’t so much a review as it is a riff, a recommendation, and it’s going to get even ramblier in a moment). You can get The Third Policeman from The Dalkey Archive, so you know it’s good, but oh-my-God-guess-what-can-you-believe-it? The Dalkey Archive is actually named after one of O’Brien’s novels, The Dalkey Archive.

So, yes, very highly recommended, read it, etc.

The rest of this riff I devote to puzzling out (without resolution) some of the marvels and conundrums of The Third Policeman; if you haven’t read the book, I suggest skipping all that follows.

I imagine that there’s a ton of criticism out there that might try to explain or elucidate the meaning of The Third Policeman, and while I’d love to hear or read some opinions on the book, I think it ultimately defies heavily symbolic readings. I suppose we might argue that the bicycle motif points toward the slow mechanization of humanity in the post-industrial landscape (or some such nonsense), or we might try to find some codex for the plot of the novel in the work of the fictional philosopher de Selby (and his critics), or we might try to plumb the novel’s mystical and religious underpinnings. It seems to me though that the absurd, nightmarish fever-joy of The Third Policeman lies in its precise indeterminacy. Here’s an example, at some length, of our narrator’s marvelous powers to describe what cannot be described:

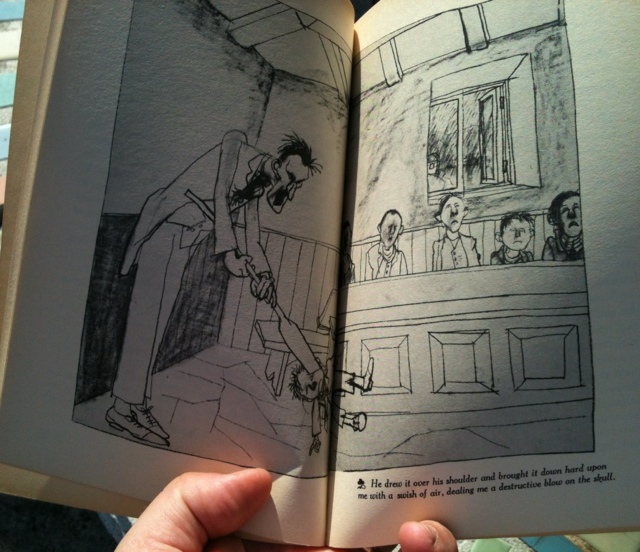

This cabinet had an opening resembling a chute and another large opening resembling a black hole about a yard below the chute. He pressed two red articles like typewriter keys and turned a large knob away from him. At once there was a rumbling noise as if thousands of full biscuit-boxes were falling down a stairs. I felt that these falling things would come out of the chute at any moment. And so they did, appearing for a few seconds in the air and then disappearing down the black hole below. But what can I say about them? In colour they were not white or black and certainly bore no intermediate colour; they were far from dark and anything but bright. But strange to say it was not their unprecedented hue that took most of my attention. They had another quality that made me watch them wild-eyed, dry-throated and with no breathing. I can make no attempt to describe this quality. It took me hours of thought long afterwards to realize why these articles were astonishing. They lacked an essential property of all known objects. I cannot call it shape or configuration since shapelessness is not what I refer to at all. I can only say that these objects, not one of which resembled the other, were of no known dimensions. They were not square or rectangular or circular or simply irregularly shaped nor could it be said that their endless variety was due to dimensional dissimilarities. Simply their appearance, if even that word is not inadmissible, was not understood by the eye and was in any event indescribable. That is enough to say.

O’Brien’s unnamed narrator repeatedly runs up against the problem of the ineffable, of the inability of language to center meaning.

The policemen—Sergeant Pluck and Policeman MacCruiskeen—are handier at navigating the absurd pratfalls of language. When the Sergeant asks the narrator if he’d like “a velvet-coloured colour,” we see the tautological, self-referential scope to description, and hence the underlying trouble of approaching pure communication. Much of the humor of The Third Policeman comes from such language. The Sergeant tells of an angry mob that “held a private meeting that was attended by every member of the general public except the man in question,” and we see the mutability of oppositions like “private/public” played to absurd comic effect.

When the policemen describe machines that break sensation into opposing and contradictory parts, we get here an anticipation of deconstruction, of the idea that difference and instability governs sensation and meaning. There is no purity:

‘We have a machine down there,’ the Sergeant continued, ‘that splits up any smell into its sub – and inter-smells the way you can split up a beam of light with a glass instrument. It is very interesting and edifying, you would not believe the dirty smells that are inside the perfume of a lovely lily-of-the mountain.’

‘And there is a machine for tastes,’ MacCruiskeen put in, ‘the taste of a fried chop, although you might not think it, is forty per cent the taste of…’ He grimaced and spat and looked delicately reticent.

The policemen’s analytic machinery correlates strongly with the narrator’s interest in philosophy and science. Through de Selby and his various critics, O’Brien simultaneously mocks and reveres the atomizing pursuits of knowledge. Delivered mostly in footnotes that would give David Foster Wallace a run for his money, the absurd philosophy of de Selby underpins the physical and metaphysical conundrums of The Third Policeman (this is, after all, the story of a man traversing a world where the laws of physics do not adhere). Here’s an early footnote:

. . . de Selby . . . suggests (Garcia, p. 12) that night, far from being caused by the commonly accepted theory of planetary movements, was due to accumulations of ‘black air’ produced by certain volcanic activities of which he does not treat in detail. See also p. 79 and 945, Country Album. Le Fournier’s comment (in Homme ou Dieu) is interesting. ‘On ne saura jamais jusqu’à quel point de Selby fut cause de la Grande Guerre, mais, sans aucun doute, ses théories excentriques – spécialement celle que nuit n’est pas un phénomène de nature, mais dans l’atmosphère un état malsain amené par un industrialisme cupide et sans pitié – auraient l’effet de produire un trouble profond dans les masses.’

This is wonderful mockery of academicese, a ridiculous idea presented with some commentary in French. At this point in the novel, I started to doubt the existence of de Selby; as the narrator’s notations of de Selby’s ideas grew increasingly bizarre, I soon realized the joke O’Brien had played on me.

And yet these jokes do not deflate the essential metaphysical seriousness of The Third Policeman: This is a novel about punishment, about crime, about damnation; this is a novel about not knowing but trying to know and describe what can’t be known or described.

This not knowing extends strongly to the reader of The Third Policeman. I was never sure if the narrator was dreaming or hallucinating or wandering through a strange afterlife—and in a way, it didn’t matter. There’s no allegorical match-up or metaphysical scorecard from which to parse The Third Policeman’s final meaning because there is no final meaning. Here’s O’Brien—or really Brian O’Nolan, I suppose; O’Brien was a pseudonym—summarizing the novel in a 1940 letter to William Saroyan:

I’ve just finished another book. The only thing good about it is the plot and I’ve been wondering whether I could make a crazy…play out of it. When you get to the end of this book you realize that my hero or main character (he’s a heel and a killer) has been dead throughout the book and that all the queer ghastly things which have been happening to him are happening in a sort of hell which he earned for the killing. Towards the end of the book (before you know he’s dead) he manages to get back to his own house where he used to live with another man who helped in the original murder. Although he’s been away three days, this other fellow is twenty years older and dies of fright when he sees the other lad standing in the door.

Then the two of them walk back along the road to the hell place and start thro’ all the same terrible adventures again, the first fellow being surprised and frightened at everything just as he was the first time and as if he’d never been through it before. It is made clear that this sort of thing goes on for ever – and there you are. It is supposed to be very funny but I don’t know about that either…I think the idea of a man being dead all the time is pretty new. When you are writing about the world of the dead – and the damned – where none of the rules and laws (not even the law of gravity) holds good, there is any amount of scope for back-chat and funny cracks.

Happily, as I mentioned earlier, I skipped the introduction and thus missed this letter, which I think deflates the novel in some ways, including the authorial spoiler. Also, O’Brien’s just plain wrong when he contends that the “only good thing about it is the plot” — there’s also the language, the ideas, the rhythm, the structure . . .

But 1940 was not ready for such a strange novel, and The Third Policeman wasn’t published until 1967, a year after its author’s death. By 1967 Thomas Pynchon had published V. and The Crying of Lot 49, John Barth has published The Sot-Weed Factor and Giles Goat-Boy, Don DeLillo had quit advertising to start writing novels, Donald Barthelme had published Snow-White, Kurt Vonnegut had gained a large audience—in short, the world of letters had caught up to O’Brien (or O’Nolan, if you prefer). Here was a post-modern novel delivered while Modernism was still in full swing.

But literary labels are no fun. You know what’s fun? The Third Policeman is fun. And unnerving. And energetic. And surreal. And really, really great. Very highly recommended.

[Ed. note—Biblioklept originally published a version of this review in May of 2012].