“Parents and Children”

by

Alberto Savinio

translated by Richard Pevear

Today, at the table, my daughter complained to her mother and me about the antipathy that we, her parents, show towards her friends of both sexes, and had shown to her little playmates when she was still a child. She added: “I make a point of not inviting my friends to the house, knowing so well how badly you’ll treat them.”

I was about to deny it, but I didn’t. My daughter’s words had enlightened me. They had clarified a feeling in me that until now had been obscure. And what they clarified most of all was the analogy that suddenly appeared to me between this feeling of mine and an identical feeling which for some time I had recognized in my daughter: the antipathy she has for my and her mother’s friends.

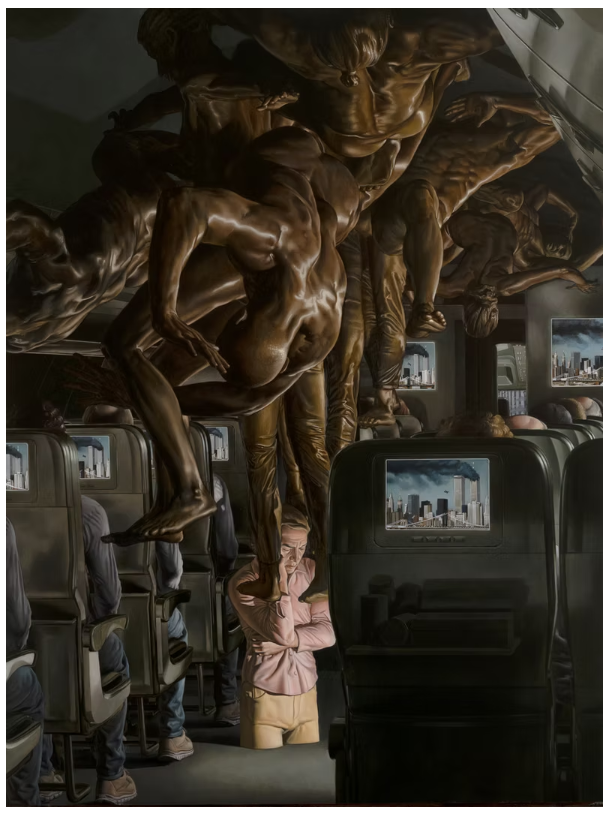

We’re at the table, as a family, united in love, and behind that veil, we are mute enemies on a silent battlefield.

The reasons for this war are the same: the will to affirm yourself, the will to deny your neighbor and, if possible, to annihilate him. Whoever it may be. Even your own father, even your own child. And if the will to annihilate your own father or your own child rarely reveals itself, that is not because it isn’t there but because it is overlaid by another will: that of affirming yourself through your own father or your own child and, beyond that, through relatives, friends, through all those who are or whom we believe are part of ourselves, an extension of ourselves, a development of our own possibilities.

At the table, my daughter’s words had revealed this usually hidden and silent will at one stroke.

Nobody spoke. We all felt the pricking of conscience under our seats.

Which of us is entirely alone? Each of us has a maniple, or a cohort, or even an army of persons by means of which he reinforces himself, extends himself, expands himself. The force of association is that much greater in the young, the more recent is the discovery in themselves of this force, its usefulness, its possibilities.

Hence that most strict, most active, most fanatical jealousy that unites my children to their friends (parts of themselves), and to their teachers, and to all that constitutes their “personal” world; hence the jealousy, though more loose, that unites me to my friends—I who also know how to fight alone; I who also know not to fight; I who am also aware of the vanity of fighting.

There are four of us at the table: a family; and behind each of us a little army is drawn up—invisible.

Rarely does the presence of this militia manifest itself; rarely does this militia have occasion to manifest itself. So complex, so various, so different, so contrary are the feelings in the heart of a single family: that mess.

But any reason at all, and the most unexpected at that, can spark a clash or even a most cruel battle. And the invisible troops go into action.

The most indirect of combats. The armies, here more than elsewhere, are passive—and indifferent—instruments. But this most indirect of combats, fought by invisible armies, is in truth the most direct of combats, fought between the most visible adversaries: husband and wife, parents and children.

The combat between parents and children is more bitter, because the children bring to it an enormous load of personal interests, a whole future of them; and the parents for their part have to defend themselves, defend the field against the threat of dispossession, against the “humiliating” danger of substitution.

And if the war between parents and children almost never ends in a fatal way, that is because at a certain point, when the battle is about to get rough, the parents and children separate; the children abandon the parents and go their own way; they understand the uselessness, the absurdity of combat with adversaries with whom, at bottom, they have nothing in common.

The battle between parents and children—the not always silent battle between parents and children—though ended not by the victory of one of the parties, but by a peaceful abandoning of the field, has its epinicium in a closer, more profound, more passionate union of the parents.

If silver anniversaries and golden anniversaries are celebrated, with even greater reason we should celebrate the new and more solemn anniversary once the children, having become adult, having left their training period behind, having become conscious of the need for a different strategy, abandon the parents and set out on their own way, towards the only true and fruitful battles, which are those that are fought between people of the same generation.

Because matrimony, that poetic song of generation (if the pun be permitted), is a pact bound with sacred ties between a man and a woman of the same generation, against other generations, against other people, all of them, including their own children. Once the children leave, the

union between husband and wife is purified of its practical reason (procreation); it withdraws into its own pure reason; it enters into the condition of poetry.

One point remained obscure to me. Why this antipathy of mine for my daughter’s friends, little men and women whom I do not know and have almost never seen; why this antipathy of my daughter’s for her mother’s friends and mine, men and women whom my daughter rarely sees, and with whom she has no common affections, feelings, tastes, interests?

I understood.

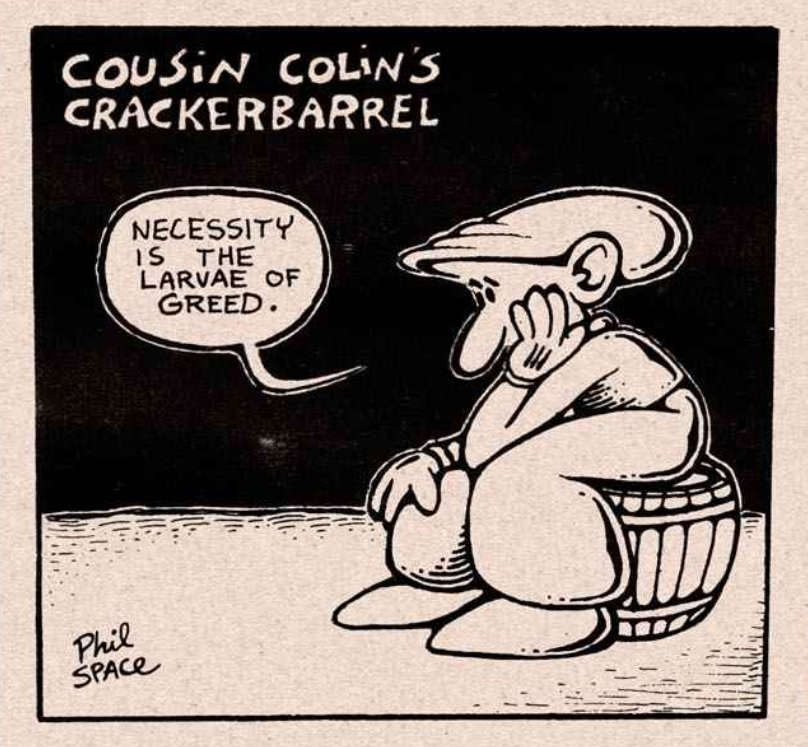

Friends, in this case, are a way of playing off the cushions (a term from billiards).

The empire of the good, in spite of so many transmutations of values, and though the reasons that first established that empire have weakened greatly and are becoming more and more confused—the empire of the good still has so much force, so much authority, that it does not allow a son to say, or even think, “I dislike my father,” nor a father to say, or even think, “I dislike my son.” But there is antipathy between fathers and sons. And even hatred. All the more antipathy, all the more hatred, insofar as the conditions for antipathy and hatred are much more frequent between those who love each other and who are united not only by love but by a common life, by common means, by a common affection for people and things, by common habits. Antipathy and hatred do not exclude sympathy and love, just as sympathy and love do not exclude antipathy and hatred. On the contrary. A strange cohabitation, but cohabitation all the same. And they either alternate, or one gains the upper hand over the other, or one hides the other—hides behind the other, as most often happens, despite the will to the good that we put into it, that we know we should put into it, that we feel a duty to put into it—that we sense the convenience of putting into it. And there is antipathy and hatred—there is “even” antipathy and hatred—of children for parents and parents for children behind love, behind great love, behind the greatest love; but since this antipathy and hatred cannot be given directly and openly to those it is destined for, the antipathy and hatred go, by an automatic transfer, and unbeknownst to the interested parties, to those who represent the “continuation” of the children, the continuation of the parents: to the friends of the children, to the friends of the parents.

The deepest ground of the drama of passion.