I. What I read

I read Alasdair Gray’s 1992 novel Poor Things. It was the second time I’d read the novel. I first read it close to ten years ago, after I read Gray’s superior but more flawed cult novel Lanark (1981).

II. What I remembered from that first reading

The basic contours of the plot; the postmodernist matryoshka-doll structure; the typography; the engravings; the art.

III. Why I reread it

Director Yorgos Lanthimos has adapted Poor Things into a film. The four films I have seen by him (Dogtooth, 2009; The Lobster, 2015; The Killing of a Sacred Deer, 2017; The Favourite, 2018) are formally daring, horrific, hallucinatory, and darkly funny.

(The final two minutes of The Favourite are absolutely hypnotic.)

I had the good fortune to see all of these films cold, with no awareness of plot or structure, and I have extended this gift to myself again with Lanthimos’ adaptation of Gray’s novel: I have avoided watching any of the trailers for the film or reading any reviews or other bright clippings. I do know the identity of some of the actors involved, but do not know which characters they play. (I assume Emma Stone is Bella.)

Of course, in rereading the source novel, I have perhaps primed myself to a first viewing of Lanthimos’ Poor Things by setting Lanthimos’ vision against its literary and visual antecedent. This might be a way of saying I am not going into his film cold.

IV. About the plot of Alasdair Gray’s Poor Things

Poor Things riffs on Shelley’s Frankenstein.

It is also a passionate defense for rationality, sexuality, feminism, and humanism. It is set primarily in the nineteenth century and in Glasgow, Scotland, but it is also set elsewhen and elsewhere.

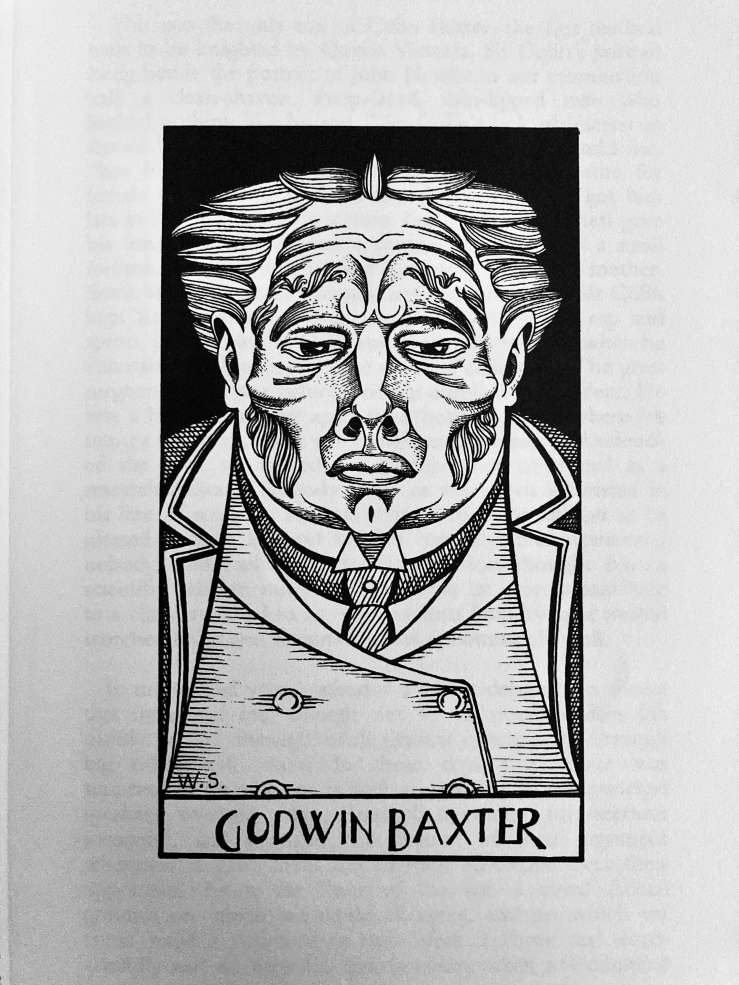

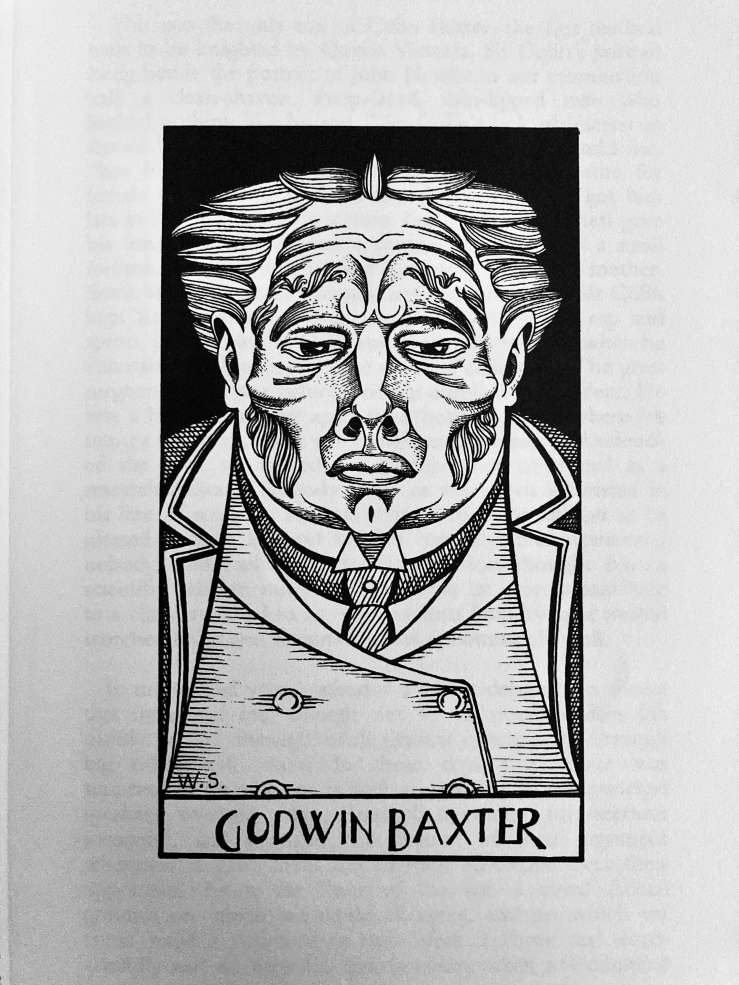

There are three primary characters: Archibald McCandless, Bella Caledonia, and Godwin Baxter. They are depicted rather allegorically on Gray’s wonderful cover for his novel, Archie and Bella cuddled up to God:

Godwin is not a mad scientist, but he does undertake some radical experiments.

Bella is the chiefest of those experiments. I will not spoil all the details. The narrative hints too that Godwin himself, surgeon son of a famous surgeon, might himself be an experimental creation.

Archibald McCandless, who narrates most of the novel, is of poorer stock than rich Godwin Baxter. A rural bastard with a chip on his shoulder, McCandless finds himself out of sync with his fellow medical students, rich boys all. But he finds a fellow to his liking in weirdo Godwin, through whom he meets Bella. He quickly falls deeply in love with the strange creature.

There are engagements, elopements, entanglements; there are dialectics, debates, debaucheries.

The rest of the plot of Poor Things should not be recounted in too much detail. It draws from Marys Shelley and Wollstonecraft; from Candide and Gray’s Anatomy, from 18th and 19th c. travelogues and Fabian Society tracts.

I should let Bella offer her own (which is to say Gray’s ironic metareflexive) dissection of the novel’s sources. In a letter that appends the narrative proper, she suggests that the “story positively stinks of all that was morbid in that most morbid of centuries, the nineteenth,” cribbing

…episodes and phrases to be found in Hogg’s Suicide’s Grave with additional ghouleries from the works of Mary Shelley and Edgar Allan Poe. What morbid Victorian fantasy has he NOT filched from? I find traces of The Coming Race, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Dracula, Trilby, Rider Haggard’s She, The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes and, alas, Alice Through the Looking-Glass; a gloomier book than the sunlit Alice in Wonderland. He has even plagiarized work by two very dear friends: G. B. Shaw’s Pygmalion and the scientific romances of Herbert George Wells.

The “he” in the text above is Archibald McCandless (although it is also of course Alasdair Gray).

V. About the structure of Alasdair Gray’s Poor Things

The narrative structure of Gray’s Poor Things is indissoluble from the plot, images, and themes. I have used the word structure in the above; perhaps presentation of events would be better. Nevertheless.

The bulk of the novel consists of a “lost” vanity-press memoir entitled Episodes from the Early Life of Archibald McCandless M.D., Scottish Public Health Officer. This narrative includes the ostensible etchings of one “William Strang” (the illustrations are of course by Gray himself).

Inside McCandless’ Episodes are nested other episodes, purportedly by other authors. First, there’s the letter from Duncan Wedderburn, once a lustful rake, now reduced to lunacy after his entanglement with Bella (his riff on Scotland and The Book of Revelations is a wonderful moment of true crankery).

Then, McCandless’s narrative gives way for quite some time to the purported letters of Bella herself, off adventuring away from Father God and Betrothed Archie. These letters are the philosophical backbone of Poor Things; the moral meat of its plot. McCandless then regains his Episodes; it ends with wonderful gothic violence.

But the novel Poor Things continues. We have another letter from Bella, now much advanced in age, herself a famous doctor, having taken up the family trade. Her silly husband Archie is dead and she’s destroyed all but a single copy of his memoir Episodes—the single copy we’ve just read. Her letter is addressed to the possible future heirs who have failed to materialize, and who thus have been spared the scandal of their antecedent’s apparent lunacy. Bella’s letter seeks to undo the gothic fantasies that preceded it, puncturing McCandless’s swollen fancies with surgical rationality while at the same time reasserting the essential feminist qualities of that precursor text. The effect is somewhat deflationary—but the novel is not yet complete!

Gray’s Poor Things is framed by two bookends, both attributed to “Alasdair Gray.”

The initial frame is “Introduction,” in which Gray explains how a friend found McCandless’s Episodes in a pile of documents that were set to be destroyed, read it, and passed it along to Gray. Gray then explains how he edited together the volume we are about to read (he “unfortunately” managed to lose the original volume in the process), cribbing it together along with Bella’s letter and some other visual materials—an assemblage, a lovely literary Frankenstein’s creature.

The final bookend is “Notes Critical and Historical.” In this section, Gray simultaneously bolsters and undermines all the narrative material that’s come before it. As one might expect from “historical” end notes, Gray (or “Gray”) lards this section with other narrative materials—anecdotes, citations, bibliographies, and interviews, among other apparent ephemera. And yet this conclusion is hardly ephemeral—indeed, the material Gray includes serves to again puncture the narratives that precede it.

Gray’s bookending gambit pays dividends in the last paragraph of the novel, by which I mean the last paragraph of “Notes Critical and Historical.” Again, I will not spoil the content here, but rather suggest that Gray has covered all his bets. The real fun in the novel is to immediately re-read the beginning: flip the frames around. Maybe fan the book about. Facts and fancies may fall out of it.

VI. An anticipation of Yorgos Lanthimos’ film adaptation of Poor Things

I have no strong emotional investment in the quality of a film adaptation of an Alasdair Gray novel. (I’m far more aesthetically invested in a possible video game adaptation of his cult classic Lanark.)

I don’t mean the previous unparantheticalized sentence to sound dismissive; to be very clear, I don’t think I’d object to any novel I loved being adapted to film or any other medium. The filmmaker might fuck up their own adaption but they could never truly affect the novel itself. At one point I think I’d have been aghast at someone’s attempt to adapt Gravity’s Rainbow or Blood Meridian; I’ve felt bad about film adaptations of Under the Volcano and Moby-Dick, no matter how grand their ambitions.

Now, I just don’t give a fuck. Go for it. Something interesting might happen, but you can’t hurt the text. At best, you’ll end up with a New Thing, which is what I expect and hope from Yorgos Lanthimos’ Poor Things. Who knows?

In rereading Gray’s Poor Things, I thought of what other filmmakers might do with the novel. Guillermo del Toro would fuss over its visuals too much at the expense of characterization. (Maybe Matteo Garrone could reign him in.) Jane Campion could likely channel its gothicism, its wit, its intellect. Peter Greenaway in his prime could have made a brilliant series of tableaux from Gray’s material. Gaspar Noé could explode a few pages of its essence over a few hours without ever getting to its core. Wes Anderson might have skillfully arranged its nested narratives, but perhaps too cleanly, too precisely even. Lars Von Trier might lean into the dirt. I suppose I could go on.

But really, while rereading Poor Things the thought that kept coming back to life was, Hey, how will Lanthimos adapt this to film?

VII. A possible answer to the above question

I hope he’s created his own beautiful monster.

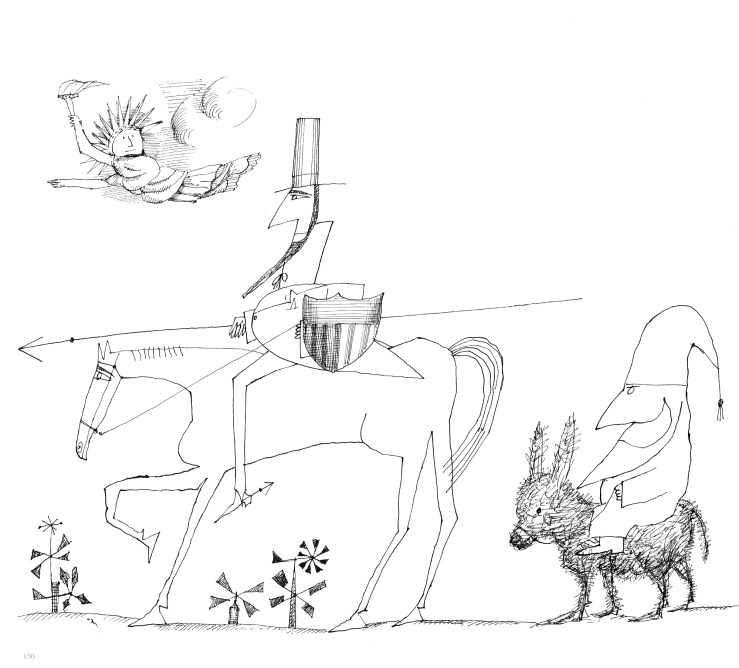

A page from Approaching Centauri by Moebius (Jean Giraud, 1938–2012)

A page from Approaching Centauri by Moebius (Jean Giraud, 1938–2012)