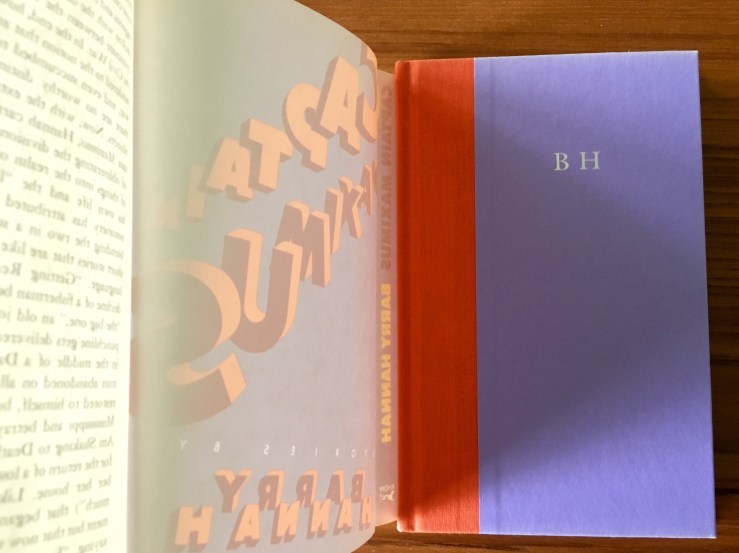

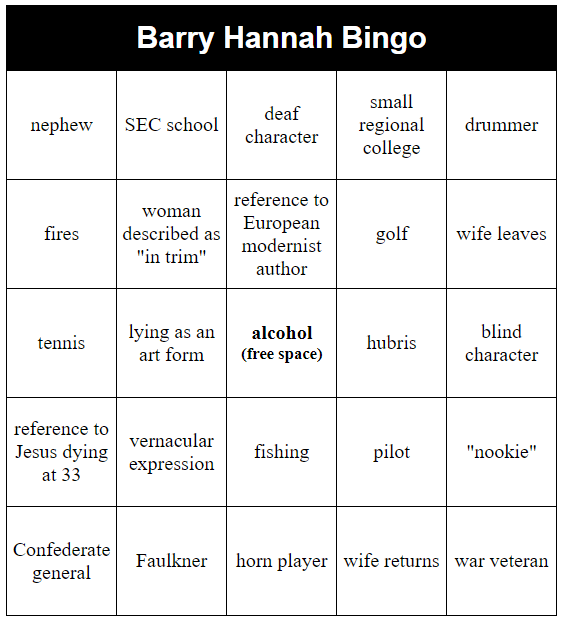

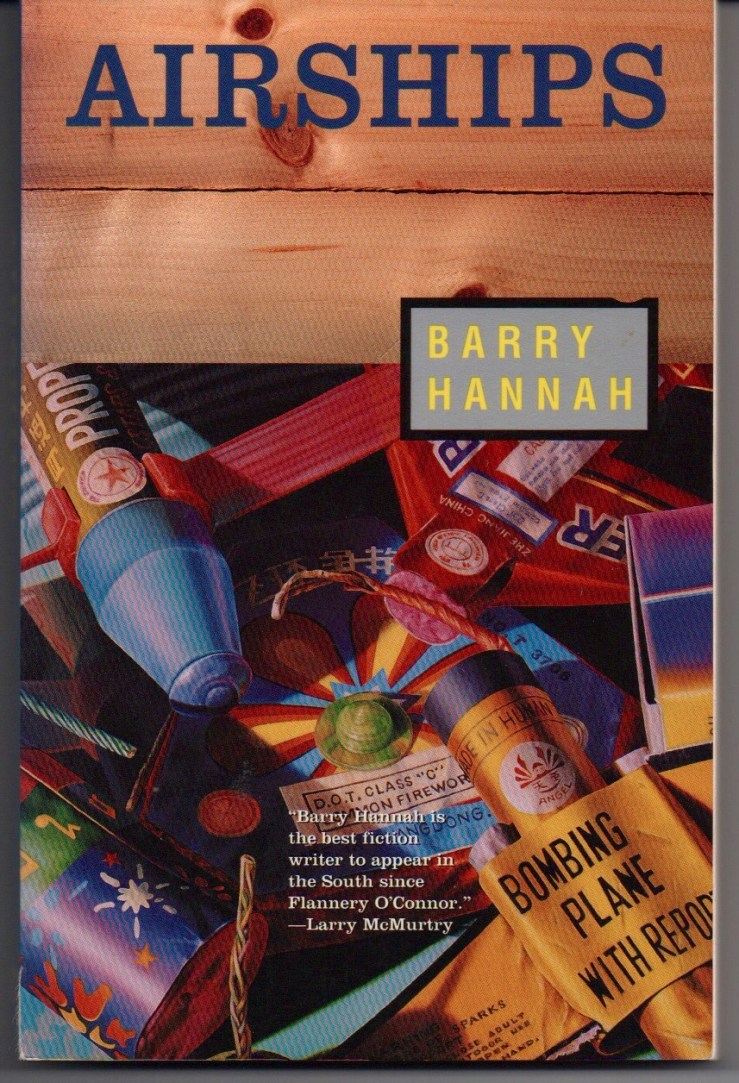

In his 1978 collection Airships, Barry Hannah sets stories in disparate milieux, from the northern front of the Civil War, to an apocalyptic future, to the Vietnam War, to strange pockets of the late-twentieth century South. Despite the shifts in time and place, Airships is one of those collections of short stories that feels somehow like an elliptical, fragmentary novel. There are the stories that correspond directly to each other — the opener “Water Liars,” for instance, features (presumably, anyway), the same group of old men as “All the Old Harkening Faces at the Rail.” The old men love to crony up, gossip, tell tall tales. An outsider spoils the fun in “Water Liars” by telling a truth more terrible than any lie; in “Harkening,” an old man shows off his new (much younger) bride. These stories are perhaps the simplest in the collection, the homiest, anyway, or at least the most “normal” (whatever that means), yet they are both girded by a strange darkness, both humorous and violent, that informs all of Airships.

We find that humor and violence in an outstanding trio of Civil War stories (or, more accurately, stories set during the Civil War). The narrator of “Dragged Fighting from His Tomb,” a Confederate infantryman relates a tale of heroic slaughter with a hypberbolic, phallic force. Observe—

I knew the blueboys thought they had me down and were about ready to come in. I was in that position at Chancelorsville. There should be about six fools, I thought. I made the repeater, I killed four, and the other two limped off. Some histrionic plumehead was raising his saber up and down on the top of a pyramid of crossties. I shot him just for fun. Then I brought up another repeater and sprayed the yard.

Later, the narrator defects, switches to the Union, and claims he kills Jeb Stuart, a figure that towers over the Civil War tales. The narrator of “Dragged Fighting” hates Stuart; the narrator of “Knowing He Was Not My Kind Yet I Followed” is literally in love with the General. In contrast to the narrator of “Dragged Fighting,” the speaker in “Knowing” — an avowed “sissy” whom the other soldiers openly detest — hates the violence and madness of war—

We’re too far from home. We are not defending our beloved Dixie anymore. We’re just bandits and maniacal. The gleam in the men’s eyes tells this. Everyone is getting crazier on the craziness of being simply too far from home for decent return. It is like Ruth in the alien corn, or a troop of men given wings over the terrain they cherished and taken by the wind to trees they do not know.

He despairs when he learns of Jeb Stuart’s death. In the final Civil War story, “Behold the Husband in His Perfect Agony,” a Union spy is given the task to communicate news of Stuart’s death through enemy lines. Rather than offering further explication, let me instead point you, dear reader, to more of Hannah’s beautiful prose, of which I have not remarked upon nearly enough. From “Behold the Husband” —

Isaacs False Corn, the Indian, the spy, saw Edison, the Negro, the contact, on the column of an inn. His coat was made of stitched newspapers. Near his bare feet, two dogs failed earnestly at mating. Pigeons snatched at the pieces of things in the rushing gutter. The rains had been hard.

The short, descriptive passage rests on my ears like a poem. Hannah, who worked with Gordon Lish, evinces in his writing again and again that great editor’s mantra that writing is putting one sentence after another.

Although set in the Vietnam War, “Midnight and I’m not Famous Yet” seems an extension of the Civil War stories. In it, an officer from a small Southern town goes slowly crazy from all the killing, yet, like the narrator of “Dragged Fighting,” he presents himself as a warrior. Above all though, he laments that the war has robbed him of some key, intermediary phase of his late youth, a phase he can’t even name—

The tears were out of my jaws then. Here we shot each other up. All we had going was the pursuit of horror. It seemed to me my life had gone straight from teen-age giggling to horror. I had never had time to be but two things, a giggler and a killer.

This ironic sense of a “pursuit of horror” pervades Airships, particularly in the collection’s most apocalyptic visions. “Eating Wife and Friends” posits an America where food shortages and material scarcity leads people to eating leaves and grass — and then each other. In “Escape to Newark,” the environment is wildly out of balance—

In August it’s a hundred fifty degrees. In December it’s minus twenty-five and three feet of snow in Mississippi. In April the big trees explode.

A plan is made to “escape” these conditions via a rocket, but of course there’s not enough fuel to get past Newark. In Airships, modes of flight are transcendent but ultimately transient. Gravity’s pull is heavy stuff.

Just as Hannah’s war stories are not really war stories, his apocalypse tales are really about human relationships, which he draws in humor, pathos, and dark cynicism. In “Green Gets It,” an old man repeatedly attempts his suicide, only to fail again and again. His suicide note, written to his daughter, is scathing and shocking and sad and hilarious and wise–

My Beloved Daughter,

Thanks to you for being one of the few who never blamed me for your petty, cheerless and malign personality. But perhaps you were too busy being awful to ever think of the cause. I hear you take self-defense classes now. Don’t you understand nobody could take anything from you without leaving you richer? If I thought rape would change you, I’d hire a randy cad myself. I leave a few dollars to your husband. Bother him about them and suffer the curse of this old pair of eyes spying blind at the minnows in the Hudson.

Your Dad,

Crabfood

Although Hannah explores the darkest gaps of the soul in Airships, he also finds there a shining kernel of love in the face of waste, depravity, violence, and indifference. This love evinces most strongly perhaps in Airships trio of long stories. These tales, which hover around 30 pages, feel positively epic set against the other stories in the collection, which tend to clock in between five and ten pages. The first long story, “Testimony of Pilot,” details the development of a boyhood friendship over a few decades. It captures the strange affections and rivalries and unnameable bonds and distances that connect and disconnect any two close friends. The second of the long tales is “Return to Return,” a tragicomic Southern drama in the Oedipal vein (with plenty of tennis and alcoholism to boot). As in “Testimony of Pilot,” Hannah finds some measure of redemption, or at least solace, for his characters in their loving friendship, yet nothing could be more unsentimental. The final long story, which closes the collection, is “Mother Rooney Unscrolls the Hurt,” a daring work of stream of consciousness that seems to both respond to — and revise — Katherine Anne Porter’s “The Jilting of Granny Weatherall.” The story concludes (and of course concludes the volume) with a vision of love that corresponds to the imagery of The Pietà, a kind of selflessness that ironically confirms the self as an entity that exists in relation to the pain of others.

I could keep writing of course — I’ve barely touched on Hannah’s surrealism, a comic weirdness that I’ve never seen elsewhere; it is Hannahesque, I suppose. Nor have I detailed Hannah’s evocations of regular working class folk, fighting and drinking and divorcing and raising children (not necessarily in that order). Airships is a world too rich and fertile to unpack in just one review, and I’ve already been blathering too long, I fear, when what I really want to do is just outright implore you, kind reader, to find it and start reading it immediately. Very highly recommended.

[Editorial note: Biblioklept published a version of this review on March 20th, 2011. I am currently listening to the audiobook of the Hannah omnibus Long, Last, Happy, and just finished the first section, which contains most of Airships. The audiobook is good, but I wish it was Hannah reading it himself.]