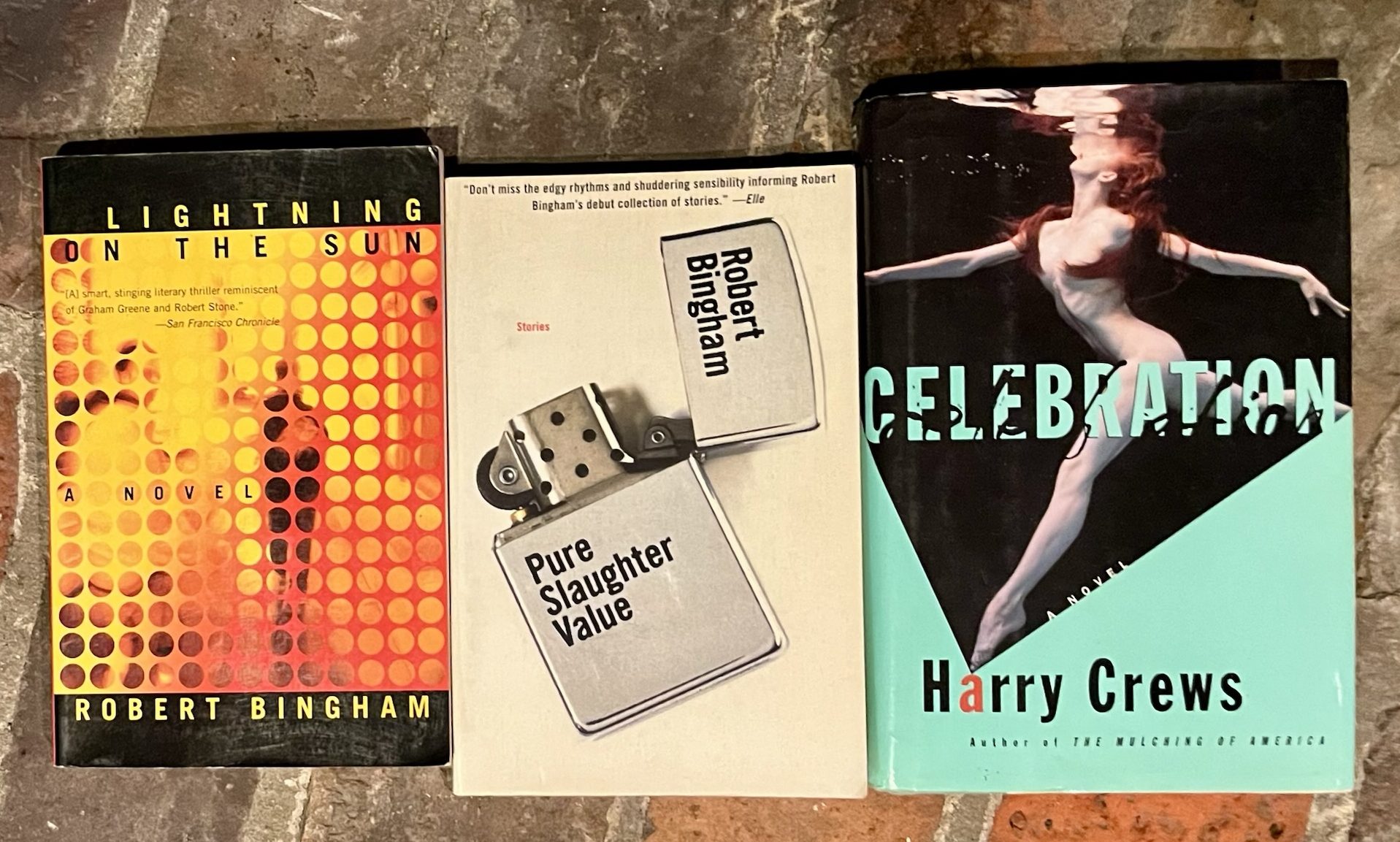

I finally gave in and picked up Robert Bingham’s books, the novel Lightning on the Sun and the collection Pure Slaughter Value.

Bingham was one of the founders of the literary magazine and press Open City. Open City published David Berman’s collection Actual Air in 1999. Bingham was friends with Berman and the Pavement boys. He was also the wealthy scion of an old Louisville family. He o.d.’d in ’99. Both Malkmus and Berman eulogized him in song — SM in “Church on White,” the Silver Jews in “Death of an Heir of Sorrows”:

I wish I had a rhinestone suit

I wish I had a new pair of boots

But mostly I wish

I wish I was with you

I think what really plugged the Bingham back into my brain was going through a July 1999 issue of SPIN magazine. I was looking for something else, but I found an old Pavement profile in which Bingham shows up early with bobo hockey tix. From the profile:

Pavement are standing outside Madison Square Garden, shouldering their way through tens of thousands of burly hockey fans. There’s a sold-out game about to start—the Rangers vs. the Mighty Ducks—and cops, peanut vendors, and entire families in matching red-white-and-blue Rangers jerseys mill about, blocking the sidewalk. “We’ve never gone to a hockey game together,” says bassist Mark Ibold. He is unceremoniously shoved aside by a squall of kids bearing cotton candy. “Usually we go see baseball games.”

Pavement pal Robert “Bingo” Bingham, a New York fiction writer, grows increasingly nervous as they approach the arena. He bought the band scalped tickets, an offense he’s been nailed for once before. “Should we come up with a fall-back strategy?” he says.

“Don’t sweat it, Bingo,” says bandleader Stephen Malkmus, still wearing the track suit and squash shoes he threw on this morning while awaiting clean laundry. The band is determined to get in, as percussionist Bob Nastanovich has already phoned his bookie to bet on the Rangers. “We don’t much care for the Ducks,” Nastanovich says.

“They’re all Steve Garveys,” adds the clean-cut Malkmus. Nastanovich takes a final drag from his Marlboro, then leads the group through the throngs to the ticket line. They cruise right in, home free—until a security squad catches up with them moments later.

“You aren’t going anywhere with those,” a guard says, motioning at the ticket stubs in Bingo’s hand. “They’re fakes.”

“Oh, please,” Bingo says. He knows they’re scalped, but fakes? A bit stunned, the band takes a look. “Well, yeah,” Ibold says. “I can see that.”

The printing is all faded and off-register.

“Mine looks like it was perforated with a cookie cutter,” says Nastanovich. Upon further inspection, they realize they all have the same seat.

Meanwhile, the Garden crowd is going ballistic. Christopher Reeve has just been wheeled onto the ice for the opening ceremony. Security hems and haws for a while, and finally takes pity on Pavement. A bearded fellow rests a cozy hand on Bingo’s arm. “You tell me who you bought these from,” he says, “and if he’s still out there, we’ll bust the fucker.”

Bingo hangs his head. “I don’t remember,” he mutters, and ambles off. Pavement trudge back to the street, reassuring their friend that the night is still young. They end up viewing the game at a nearby sports bar, and work on getting stinking drunk. Nedved is benched. Gretzky is checked. The once formidable Rangers lose handily, 4–1. Nastanovich looks up from his Bass Ale and shakes his head, laughing. He just lost $100.

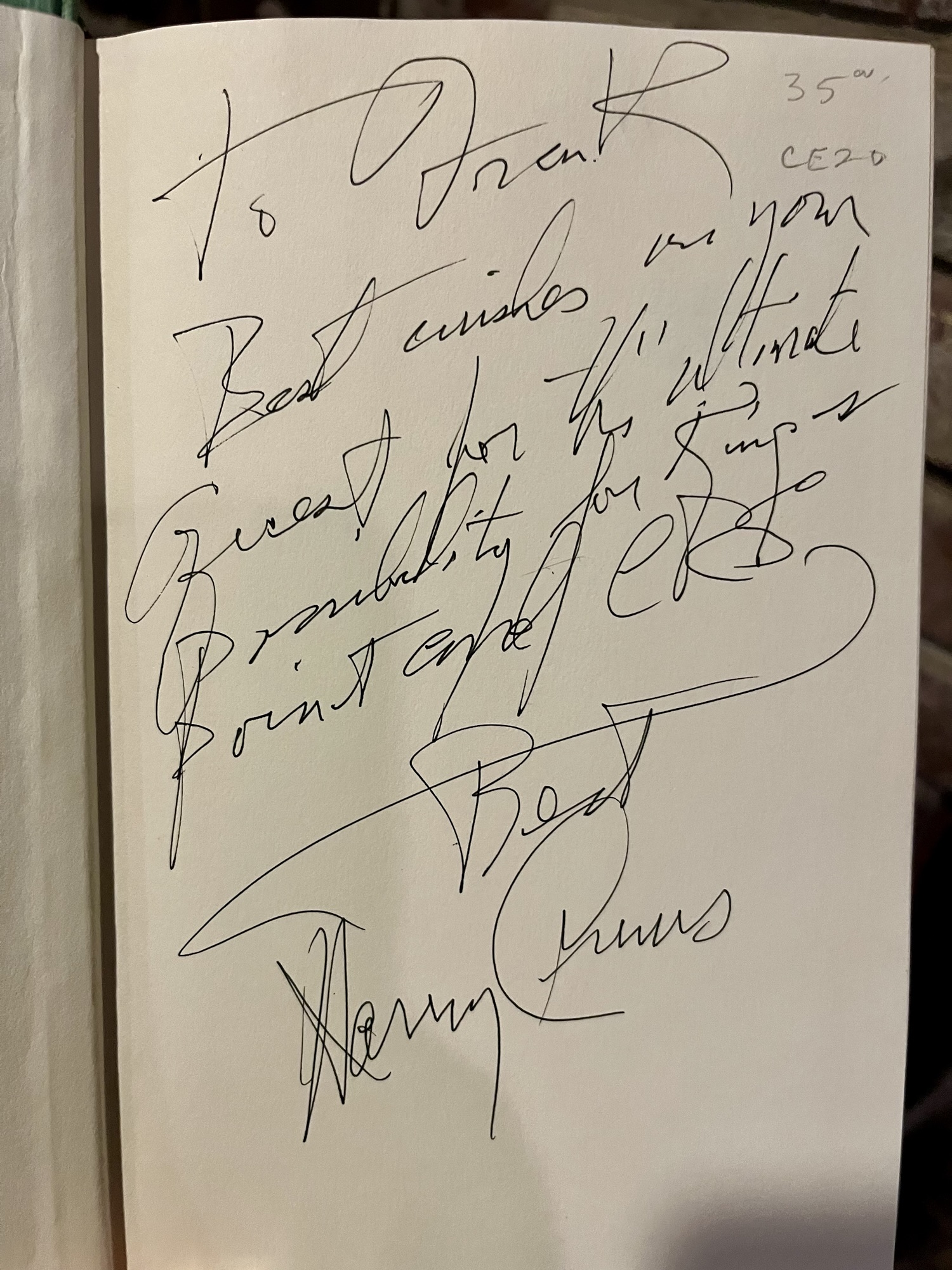

I also couldn’t resist a signed copy of Harry Crews’ 1998 novel Celebration.

If you can make out the inscription, let me know. I think it’s to Frank, who was on the ultimate quest for…?