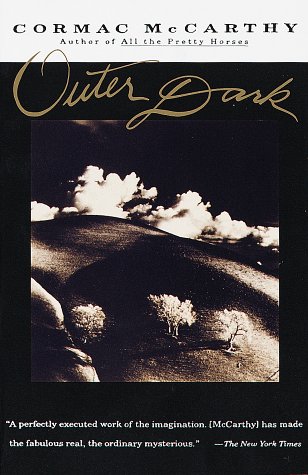

In Cormac McCarthy‘s second novel, Outer Dark, set in the backwoods and dust roads of turn-of-the-century Appalachia, Culla Holme hunts his sister Rinthy, who has abandoned the pair’s shack to find her newborn baby. Culla has precipitated this journey by abandoning the infant in the woods to die; a wandering tinker finds the poor child and absconds with it. As Rinthy and Culla independently scour the bleak countryside on their respective quests, a band of killers led by a Luciferian figure roams the wilderness, wreaking violence and horror wherever they go.

In a recent interview with the AV Club, critic Harold Bloom noted that Cormac McCarthy “tends to carry his influences on the surface,” pointing out that McCarthy’s major influence, William Faulkner, tends to proliferate throughout McCarthy’s early work to such an extent that those works (The Orchard Keeper, Outer Dark, Child of God, Suttree) suffer to a certain degree. Indeed, it’s hard not to read Outer Dark without the Faulkner comparison invading one’s perception. It’s not just McCarthy’s Appalachian milieu, populated with Southern Gothicisms, hideous grotesques, rural poverty, incest, and a general queasiness. It’s also McCarthy’s Faulknerian rhetoric, his elliptical syntax, his dense, obscure diction, his bricks of winding language that seem to obfuscate and resist easy interpretation. Like Faulkner, McCarthy’s language in Outer Dark functions as a dare to the reader, a challenge to venture to the limits of what words might mean when compounded. And while the results are sometimes (literally) startling, they often strain, if not outright break, the basic contract between writer and reader: at times, all cognitive sense is lost in the word labyrinth. Take the following sentence that ends the first chapter, where Culla looks back on the infant he has just abandoned:

It howled execration upon the dim camarine world of its nativity wail on wail while lay there gibbering with palsied jawhasps, his hands putting back the night like some witless paraclete beleaguered with all limbo’s clamor.

A “paraclete” is someone who offers comfort, an advocate. I’m thinking that the “jawhasps” must be a twisted mouth. No idea what “camarine” means. But it’s not just the obscure diction here: the whole action is obscure (how does one go about “putting back the night”?). This confusing passage is hardly an isolated incident in Outer Dark; instead McCarthy repeatedly employs long, dense, nearly unintelligible sentences, constructions that defy the reader’s ability to visualize the words he or she is being asked to decode. This unfortunate tendency alienates the reader in ways that are no doubt intentional, yet ultimately unproductive. More often than not, McCarthy’s long twisting hydras of obscurantism are not so much moving or thought-provoking as they are laughably ridiculous, and while his vocabulary is surely immense, it’s hard enough to get through such abstract sentences without having to run to a dictionary every other word.

Readers of mid-period, or even more recent McCarthy works will no doubt recognize this complaint, so it’s important to note that we’re not talking about the density and alienating syntax of Blood Meridian, the philosophical pontificating of The Border Trilogy, or the occasional run-to-a-thesaurus word choice one can find in The Road. No, Outer Dark is full-blown Faulkner-aping (Faulkner at his worst, I should add); over-written, ungenerous, and just generally hard to get into, especially the early part of the novel which is particularly guilty of these crimes. Which is a shame, because once one penetrates the wordy exterior of the first few chapters, there’s actually a pretty good novel there. While no one could accuse Outer Dark of having a tight, gripping plot, the intertwined tales of Culla and Rinthy–and the band of outlaws–gives McCarthy an excellent venue to showcase his biggest strength in the novel–the dialogue.

Spare and terse, the strange, strained conversations between McCarthy’s Appalachian grotesques are often funny, usually tense, and always awkward. Culla and Rinthy are outcasts who don’t quite understand the extent of their estrangement from the dominant social order. They frequently encounter fellow outcasts, often freaks of a mystical persuasion, like the witchy old woman who frightens Rinthy, or the old snake-trapper who freaks out Culla (a task not easily achieved). The dialogue between McCarthy’s characters reads with authenticity and intensity, and the author gets far more mileage out of the gaps in conversation, the elisions, the omissions–what is not said, what cannot be said. These odd characters culminate in the trio of outlaws who terrorize the fringes of Outer Dark. Their ominous black-clad leader prefigures many of McCarthy’s later antagonists, like the Judge of Blood Meridian or Chigurh in No Country for Old Men, but he pales in comparison to the former’s eloquent anarchy and the latter’s bloody intensity. McCarthy doesn’t really seem to know what to do with him, to tell the truth. Still, fans of Chigurh and the Judge will find the roots of those characters in this unnamed villain, and will probably have some interest in McCarthy’s evolution of this type.Indeed, it’s tracking this progression of themes and types throughout McCarthy’s body of work that was of the greatest interest to me, and in turn, I suspect that Outer Dark is probably going to be of greatest interest to those who’ve been reading McCarthy more or less chronologically backwards (like I have). It’s certainly not the starting place for this gifted author, and while its early dense prose will certainly provoke a few mournful groans, the end of the book redeems the bog of language at its outset.