INTERVIEWER

Then you consider your novel a purely literary work as opposed to one in the tradition of social protest.

ELLISON

Now, mind, I recognize no dichotomy between art and protest. Dostoyevsky’s Notes from Underground is, among other things, a protest against the limitations of nineteenth-century rationalism; Don Quixote, Man’s Fate, Oedipus Rex, The Trial—all these embody protest, even against the limitation of human life itself. If social protest is antithetical to art, what then shall we make of Goya, Dickens, and Twain?

Tag: Literature

Matt Bell Chats with Biblioklept About Apocalypse, Hairy Infants, Cures for Writer’s Block, and His New Book Cataclysm Baby

When an advance copy of Matt Bell’s new novella-in-stories Cataclysm Baby showed up in the mail a few months ago, I was immediately intrigued. Post-apocalyptic fiction is right up my proverbial alley, and the book’s conceit—Bell’s site describes the book as “twenty-six post-apocalyptic parenting stories, all narrated by fathers, each revealing some different family, some new end of the world”—seemed refreshingly different than the “family issues” novels that publishers tend to send my way. I was not a jot disappointed in Cataclysm Baby either; in my review I write:

Bell’s apocalypse is discontinuous; each tale evokes its own paradigm, its own idiom of grief. He’s less interested in the invention and world-building that marks so much of sci-fi and fantasy than he is in tapping into the mythological undercurrents of end-of-the-world narratives. The short pieces in Cataclysm Baby unfold (or burst, or twist) like strange, dark fairy tales, each proposing another vision of collapse.

Matt was kind enough to talk to me over an exchange of emails. In the margins of our exchanges—those little quips that aren’t part of the interview proper—I found Matt to be a very nice, generous fellow. I enjoyed talking with him.

Matt teaches writing at the University of Michigan; he also works for Dzanc Books, where he runs the literary magazine The Collagist.

Cataclysm Baby, new from indie Mud Luscious Press, is Matt’s second book after the collection How They Were Found.

Biblioklept: Cataclysm Baby is a highly structured work that follows a clear pattern. Where did Cataclysm Baby begin? At what point did you start using the alphabet as an organizing principle for apocalypse family fiction?

Matt Bell: The writing of Cataclysm Baby began with its first story, “Abelard, Abraham, Absalom,” although I didn’t have that title for it then: I was just starting off to write a standalone short about this father, who was describing the birth of his son in what turned out to be fairly grim circumstances, and I didn’t know anything more than that—as is often the case with me, I was probably more interested in the voice than in the content or the character, at least at the very beginning. At some point in that draft, I wrote an early version of these lines: “For our baby, a name chosen from a book of names. Each name exhausted one after another, a sequence failure.” It was that suggestion of the baby name book that offered up that narrative’s title, and then alphabetizing as an organizing principle for more stories. Before that, I hadn’t intended to write a series, or this novella that they became, but the book’s structure was held in those lines, and that structure ended up driving a lot of the rest of the book’s drafting, by giving a shape for the other narratives to attach to.

Biblioklept: “Abelard, Abraham, Absalom” contains a horrifying image—the baby is born with a “furred esophagus,” and the dad must pull a hairball from the baby’s mouth. The following stories build on this horror: mutant offspring, forced-breeding, still birth, monster birth . . . You say that your initial concern was more with voice than content or character—but did you have any of these images in mind at the outset?

MB: It’s always a little hard to remember exactly—I wrote the first drafts of Cataclysm Baby in mid-2009—but I think that I would probably say that I didn’t have the imagery of the “furred esophagus” and that hair-choked baby before I started, but I might have had some of the others before starting their sections. Some of the sections were suggested by the names I chose, which in certain cases came first: Including the name “Cain” in the title of the third story, for instance, suggested at least a fratricide, if not exactly what that killing might entail.

For the most part, I’m typically not much of a planner, at the plot or situation level: I don’t have particularly good ideas, and so if I start there, I tend to end up with stories that are all surface, or that at least capture only the most surface stuff of me. By starting at the level of the sentence or the sound or the image—and then by staying at that level as long as I can—I feel more likely to dredge a little deeper, to discover something a little stronger. It’s in subsequent drafts that I do a lot of the plot and character shaping, and even some of the conceptual thinking. I need a certain critical mass of workable language before I can do too much story-work with it.

Bibliokept: Your language—tone, syntax, diction, etc.—inheres across the collection and works to unify the themes and images in Cataclysm Baby. Still, there’s a sense of disconnection of time and place between these stories, as if each one is its own discrete apocalypse or dystopia, even as they blend together.

In a sense, you seem to be playing obliquely with the tropes of end-of-the-world fiction, but resisting the heavy exposition and tendency for world-building we see in so much sci-fi. I suppose I’m pointing toward what I see as restraint in CB, but might have actually been editing on your part—how much of CB came from pruning and paring down?

MB: Generally I’d say that it’s my process to overwrite and then to cut back to the best version of any given story. That said, Cataclysm Baby was never a dramatically longer book, either as a whole or in its individual pieces. For me, many of these stories often operate more like fairy tales or biblical stories than contemporary sci-fi, and so have to do their world-building in different ways. I often write in fragments, and try to create useful spaces in the white spaces between—some regions of ambiguity or juxtaposition—and I think that when that’s working well those regions can end up standing in for what might otherwise require a lot of connective tissue and explanatory exposition.

Biblioklept: Why are end of the world stories are so compelling?

MB: The apocalyptic goes deep in us: Every civilization has its origin story, and also its story of how it’ll all end. Less of us might believe in more supernatural apocalypses now than in the past, but we’ve replaced those fears with secular ones, made all the more frightening for being manmade—global warming and constant war and economic inequality are the results of choices we’ve made, not the supernatural nature of the universe. We’re also within the first few generations that grew up during the environmental movement, taught to see the earth as something that needed to be saved by human action, from human action. All that adds to the gravity of certain kinds of apocalyptic stories: Our ending is now an act of agency instead of prophecy, and for me that changes everything.

Biblioklept: In what ways?

MB: What I mean is that if the end of the world is completely out of our control—if it’s the second coming or an unstoppable asteroid headed for earth —then we don’t bear any responsibility for it happening, and probably be can’t be tasked with stopping it. But if it’s a side effect of the way we live or the way we exploit the earth’s resources or of the way we treat each other, then I think we can be held responsible, both for what has already happened and our failures to make things better. The problem is that most of don’t actually have the chance to make a direct impact, or at least we don’t get to feel like we’re making one very often. It’s hard to make the links between our individual lives and our communal fates, in the biggest ways. But that doesn’t free us from the anxiety or the fear: If anything it probably makes it worse, because someone is making the decisions that might cost us everything, but it’s hard to pin down who it is, or to hold them accountable for their actions.

To bring it back toward Cataclysm Baby: The fathers in the book are rarely if ever responsible for the situations they and their families are in, and they aren’t generally given opportunities to improve things in a large-scale way. All they can do is focus on themselves and their families—which is, of course, what most of us do too, no matter how badly things are going outside our doors. This tension between what we know is wrong (climate change and oppression and war and every other kind of global problem) and what we are best suited for (caring for ourselves and the people closest to us) is problematic, and the solutions to that closing that gap aren’t particularly obvious, or at least they’re not obvious to me.

Biblioklept: I think that Cataclysm Baby has a positive ending—not necessarily a happy ending—but a positive one, or at least one that points to a future and generative capability. I’m curious if you tried out other ways to close the collection than those last few lines of “Zachary, Zahir, Zedekiah.”

MB: I’m so glad you read the ending that way: It’s definitely not a happy ending—and couldn’t be, after what’s come before—but I’d like to think that it at least leaves open the possibility of hope. That seems like such a slim solace, but it’s something, and sometimes enough.

As for whether there were other ways to end the novella: As I said above, I’m not generally a planner, and I ideally like to reach the final pages of a book or story in a burst, writing headlong, possessed by a sort of measured recklessness, in hopes that by moving as strongly as possible from sentence to sentence in a controlled sprint I might arrive at the end surprised and invigorated by what I find there, rather than overthinking or over-determining it. The final sentence of Cataclysm Baby was almost certainly tweaked through the rewriting process, but I arrived at its basic shape for the first time in much the same way I imagine a reader might, coming out of that run of repetitions and endings into something else, some possible future. I was glad that it contained that hope you felt, glad to know that was the way I instinctively responded when I reached the last page.

Biblioklept: Cataclysm Baby bears two epigraphs; one from the King James bible, and one from Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. The content of both quotations resonates with your work, as does the style.

McCarthy has said that “books are made out of books.” What writers or books were especially important or influential when you were composing Cataclysm Baby?

MB: I love that McCarthy quote, and couldn’t agree more: I think that for me a lot of my formative experiences didn’t happen in “real life,” but inside of books, in that space between what’s printed on the page and what happens in the reader. So the books I’ve read are at least as important an influence as the things I’ve done.

The Bible is obviously an influence on the voice of the book, but it also owes a debt to texts like Beowulf or the Greek myths—there’s a purposeful attempt here to use a more archaic-seeming way of speaking to talk about these futures. Fairy tales are an important part of how I structure stories and character development, and I think that way of thinking was a huge help when working with all of these compressed narratives. And of course there are all the end-of-the-world tales I read when I was a kid or a teenager or more recently: I grew up almost exclusively on science fiction and fantasy and horror, and so much of that still filters into the work. It’s some of that stuff from when I was younger that sticks with me the most, the different world-ending plots of Swan Song and The Stand and Robots and Empire and so on. And then there’s stuff I read later, like Beckett’s Endgame, like Shirley Jackson and McCarthy and Brian Evenson. But of course all of this is over-simplifying, or choosing only the most direct or obvious choices, the ones I couldn’t deny anyway: As I said above, I’ve lived a rather large part of my life inside the books I love, and so it’s no surprise that part of my books would end up being set in some combined world, some landscape they’ve all been mashed into inside me.

Bibliokept: You work as both an editor and a writing teacher. How do those jobs overlap or contrast or influence your own fiction writing?

MB: By the time I finished grad school I was doing most of these things in some form: I was teaching writing there too, and I’d started The Collagist and was just about to join Dzanc full-time. I truly love my teaching and my editing, and am very grateful to have them both as part of my daily work. I think that more than anything they’ve allowed me to see all of these pursuits as part of a bigger literary life, and that this life was the real goal I wanted to realize. I’m very lucky to get to spend my days as a writer and as a reader and teacher and editor and reviewer and whatever else, and I think that all of these different activities add up to one satisfying whole. If there ever came a time when I couldn’t write—where I lost my nerve or my drive to create—I’d like to think that these other activities might sustain me through that loss.

Biblioklept: What about just plain old writer’s block? I seem to be suffering from it these days. Any suggestions you offer your students?

MB: First, my sympathies: I know how frustrating that sensation can feel. Personally, I think I rarely have true writer’s block, the kind where I don’t write. Instead I have days where I write only badly, and sometimes miserably so —and sometimes those days stretch into weeks. When I’m working on a project, there’s almost always something to do, so if I can’t go forward I just move backward in the story and try to revise my way into forward motion again. If I’m between projects, I try to start something new every day until one catches. Immediately after finishing Cataclysm Baby I must have written the beginnings of a dozen terrible short stories, not letting myself abandon one before my writing time was over for the day. So maybe I spent a month writing three or four hours a day on work I wasn’t going to continue with—but at least I was writing. That’s the only way I know to get past writer’s block that isn’t dumb luck.

Biblioklept: Obviously Cataclysm Baby is just out, but do you have any other books or writing projects on the horizon?

MB: I do, thankfully: I’ve been working almost exclusively on a novel for the past three years, and am in the very final phases of that book. I can’t say much more about it yet, but hopefully soon. Once that’s finished, who knows? I’m looking forward to getting back to that place of surprise and uncertainty, after a couple years of knowing what to work on every day.

Biblioklept: Have you ever stolen a book?

MB: Not from a store, I don’t think. Mostly, I probably have some borrowed books I never gave back, and after some number of years those have become something like a theft. When I was 21 or so, I believed someone lent me a copy of Sam Lipsyte’s Venus Drive, which absolutely blew me away, and was hugely influential on me as a writer. I had no idea who Lipsyte was, and at the time there weren’t any other books of his to read. I was sure my friend Irene had borrowed me the book, but she said she hadn’t, and later I tried to return it to a few other friends, but they wouldn’t claim it either. So maybe I did buy it, but I don’t remember doing so, and every time I see it on the shelf I wonder who it really belongs to. Assuming it does belong to some friend of mine, I owe them far more than the cover price: I wouldn’t be the same writer without having found Lipsyte then, or even the same person.

Books Acquired, Some Time Over the Past Two Weeks

“to sex brawl and dare” — A Poem from Surrealist Ghérasim Luca

The good people at Contra Mundum Press are putting out the first English language translation of Romanian surrealist Ghérasim Luca’s Self-Shadowing Prey. Mary Ann Caws translates. Here’s the first poem in the book:

at the edge of a forest

whose trees are slender ideas

and each leaf a thought at bay

the vegetal reveals to us

the damned depths of an animal sect

or more precisely

an old insect anguish

waking up as man

the only way

the only basic weapon

to animate a mental state

that I hurry to write mantil

like a mantis

if only to mark

with a dry warning laugh

the devouring word

Entity and antithesis of the bush

a sort of wild and organic brush

grows in the head of that man

ravaged

by the heresy of parks and greenhouses

like the orgasm of a key

a lovely door

So the legendary passivity

the famous and ample passivity of plants

changes here to idle hate

to mad rage

to sex brawl and dare

luring by sap blood lava . . .

as rapid as the passage of woman

to beast

she empties us of a foul ancestral

wound

which in a spurt relieves us

of these fixed plaints

and these false death rattles plumbing us

our calm gestures of the interred

Now only terror

is still able to insert

in the tropism of body and of guilty

spirit

this prism as doubled echo

where brains and senses capture

the violent innocence

of a flora and a fauna

whose marriage is a long seizure

and a rape as slow as gold

in the implacable lead

And it’s around the mental equator

in the space delimited by the tropics

of a head

at the angle of the eye and what surrounds it

that the myth of a kind of utopian

jungle surges into the world

As virgin as the unknowable

or the other “face” of the moon

and never in the reach of a gun

or an axe

its prey is the snow

sand ball hip if not the trap

that the diffuse breath of a dream

lights up

For tangled

soldered to massive corkscrew keys

the vines

the branches stoves and rituals

fuse

around the forms placed

as if by miracle

at the crossroads of dryads

of druids and of man

So many points to aim at

all these yes and nos that

outside outside of time

of space and weight

select a sort of coupled oasis

and hamlet

to descend in these gods

from before the ages

the gods-place-beast-island-ash-fire

come forth as from the coupling of bird

and branch

and those exiled from the center

and from the shade of a golden foliage

will adore one day

between the walls of their somber cities

Book Shelves #19, 5.06.2012

Book shelves series #19, nineteenth Sunday of 2012.

When I started this project, this shelf was all Tolkien and Joyce; now it’s mostly Gaddis and Joyce.

I have dupes of most of the Joyce books here; there’s also Joyce criticism/guides on the shelf.

Another angle. Glare is horrible. iPhone is not a good camera; lots of glare; shelf is much taller than me, etc.:

Here’s a tight shot of the Brownie Six-16 that serves as bookend:

Something from Finnegans Wake :

Steinbeck on Critics: “Curious Sucker Fish Who Live with Joyous Vicariousness on Other Men’s Work”

ON CRITICS

This morning I looked at the Saturday Review, read a few notices of recent books, not mine, and came up with the usual sense of horror. One should be a reviewer or better a critic, these curious sucker fish who live with joyous vicariousness on other men’s work and discipline with dreary words the thing which feeds them. I don’t say that writers should not be disciplined, but I could wish that the people who appoint themselves to do it were not quite so much of a pattern both physically and mentally.

I’ve always tried out my material on my dogs first. You know, with Angel, he sits there and listens and I get the feeling he understands everything. But with Charley, I always felt he was just waiting to get a word in edgewise. Years ago, when my red setter chewed up the manuscript of Of Mice and Men, I said at the time that the dog must have been an excellent literary critic.

Time is the only critic without ambition.

Give a critic an inch, he’ll write a play.

From John Steinbeck’s 1969 interview in The Paris Review.

“Effect of Quantity” (Nietzsche on Shakespeare)

162. Effect of Quantity. —The greatest paradox in the history of poetic art lies in this: that in all that constitutes the greatness of the old poets a man may be a barbarian, faulty and deformed from top to toe, and still remain the greatest of poets. This is the case with Shakespeare, who, as compared with Sophocles, is like a mine of immeasurable wealth in gold, lead, and rubble, whereas Sophocles is not merely gold, but gold in its noblest form, one that almost makes us forget the money-value of the metal. But quantity in its highest intensity has the same effect as quality. That is a good thing for Shakespeare.

From Human, All Too Human, Part II by Friedrich Nietzsche.

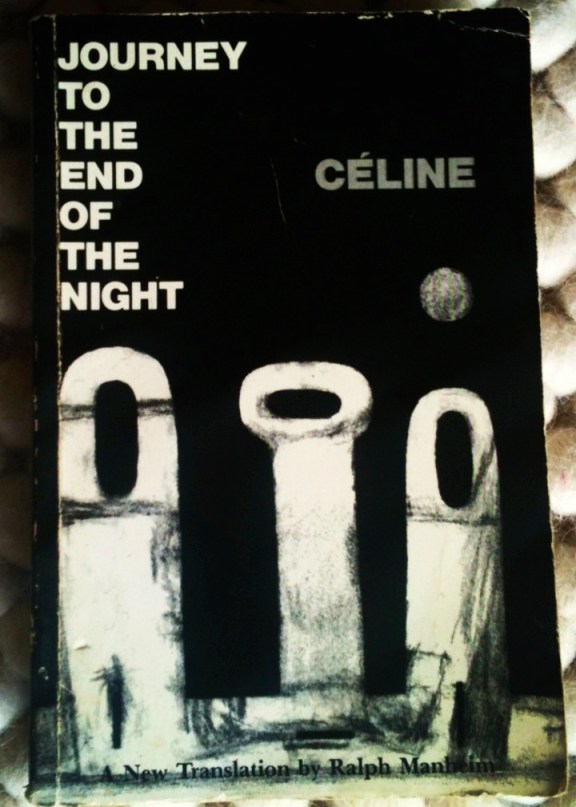

Book Shelves #17, 4.22.2012

Book shelves series #17, seventeenth Sunday of 2012.

Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Steinbeck, Camus, Nabokov, Celine, Kafka.

Jonathan Littell’s The Kindly Ones with Revere movie camera as bookend. Littell’s lurid, bizarre book is only shelved here temporarily (he’s in too-rarefied company, perhaps).

A friend gave me this in high school.

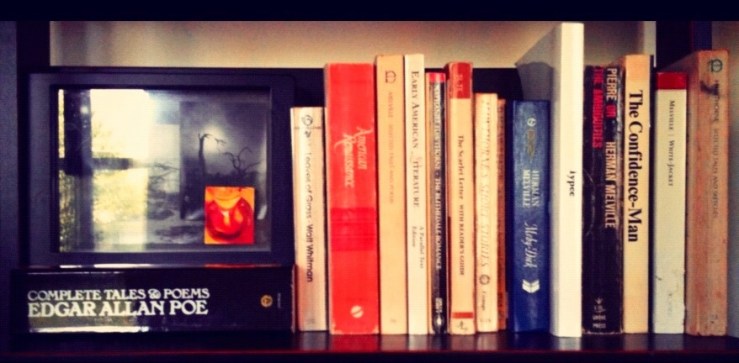

Book Shelves #16, 4.15.2012

Book shelves series #16, sixteenth Sunday of 2012.

It’s hard to photograph books, and using an iPhone 3gs probably doesn’t help. Lots of glare. Anyway: This shelf houses mostly Melville, with some Hawthorne, Poe, and Whitman, as well as some critical works on the American Renaissance movement. (Henry James and F.O. Matthiessen). I have other versions of a lot of these books, including a fraternal twin in my office, a bit bulkier (Emerson, Dickinson, Thoreau, etc.), although these days I’m apt to go to the Kindle for American Renaissance stuff. Here’s a better angle, perhaps:

The version of Typee is bizarre: no colophon, no publisher info, just text. I love these midcentury Rinehart Editions of Hathorne and Melville stuff:

“Walter, Leave Off” — D.H. Lawrence on Walt Whitman

From Lawrence’s chapter on Whitman in Studies in Classic American Literature (more):

POST-MORTEM effects?

But what of Walt Whitman?

The ‘good grey poet’.

Was he a ghost, with all his physicality?

The good grey poet.

Post-mortem effects. Ghosts.

A certain ghoulish insistency. A certain horrible pottage of human parts. A certain stridency and portentousness. A luridness about his beatitudes.

DEMOCRACY! THESE STATES! EIDOLONS! LOVERS, ENDLESS LOVERS!

ONE IDENTITY!

ONE IDENTITY!

I AM HE THAT ACHES WITH AMOROUS LOVE.

Do you believe me, when I say post-mortem effects ?

When the Pequod went down, she left many a rank and dirty steamboat still fussing in the seas. The Pequod sinks with all her souls, but their bodies rise again to man innumerable tramp steamers, and ocean-crossing liners. Corpses.

What we mean is that people may go on, keep on, and rush on, without souls. They have their ego and their will, that is enough to keep them going.

So that you see, the sinking of the Pequod was only a metaphysical tragedy after all. The world goes on just the same. The ship of the soul is sunk. But the machine-manipulating body works just the same: digests, chews gum, admires Botticelli and aches with amorous love.

I AM HE THAT ACHES WITH AMOROUS LOVE.

What do you make of that? I AM HE THAT ACHES. First generalization. First uncomfortable universalization. WITH AMOROUS LOVE! Oh, God! Better a bellyache. A bellyache is at least specific. But the ACHE OF AMOROUS LOVE!

Think of having that under your skin. All that!

I AM HE THAT ACHES WITH AMOROUS LOVE.

Walter, leave off. You are not HE. You are just a limited Walter. And your ache doesn’t include all Amorous Love, by any means. If you ache you only ache with a small bit of amorous love, and there’s so much more stays outside the cover of your ache, that you might be a bit milder about it.

I AM HE THAT ACHES WITH AMOROUS LOVE.

CHUFF! CHUFF! CHUFF!

CHU-CHU-CHU-CHU-CHUFF!

Reminds one of a steam-engine. A locomotive. They’re the only things that seem to me to ache with amorous love. All that steam inside them. Forty million foot-pounds pressure. The ache of AMOROUS LOVE. Steam-pressure. CHUFF!

An ordinary man aches with love for Belinda, or his Native Land, or the Ocean, or the Stars, or the Oversoul: if he feels that an ache is in the fashion.

It takes a steam-engine to ache with AMOROUS LOVE. All of it.

Walt was really too superhuman. The danger of the superman is that he is mechanical.

Oscar Wilde’s Letter to Walt Whitman

Partial transcript from The Library of Congress:

Before I leave America I must see you again–there is no one in this wide great world of America whom I love and honour so much. With warm affection, and honourable admiration, Oscar Wilde.

The Walt Whitman Archive fleshes out the story:

On 18 January 1882 Wilde visited Walt Whitman in Camden, where the poet was then living with his brother and sister-in-law. Wilde told Whitman that his mother had purchased a copy of Leaves of Grass when it was first published, that Lady Wilde had read the poems to her son, and that later, at Oxford, he and his friends carried Leaves to read on their walks. Flattered, Whitman offered Wilde, whom he later described as “a fine large handsome youngster,” some of his sister-in-law’s homemade elderberry wine, and they conversed for two hours. Asked later by a friend how he managed to get the elderberry wine down, Wilde replied: “If it had been vinegar I would have drunk it all the same, for I have an admiration for that man which I can hardly express”

The Pale King Paperback (Book Acquired, 4.07.2012)

I was happy to get a trade paperback of David Foster Wallace’s The Pale King this weekend (thanks Hachette!) for a few reasons. First, I detest hardback books — that didn’t stop me from picking up (and reviewing) TPK when it debuted last year — but I know I’ll prefer this paperback for rereadings. More to the point, the paperback boasts four vignettes not published with the hardback last year, which I’m sure is in no way a cynical marketing ploy cooked up by the publishers. On those scenes:

Okay, so yes, I read them. They’re short, and they don’t really add to the novel; actually, they probably take away from the Michael Pietsch’s fine editing work. Still, DFW fans will eat them up. I’ll try to reflect more later.

There’s also one of those reading group guide sections, which cracks me up. Are book clubs gonna read this book? I mean, I hope they do, but they’ll likely hate it. Here’s a question that caught my eye, mostly because I wrote a bit about §19 this summer.

Barry Hannah Fragment

From Barry Hannah’s novel Hey Jack!:

I began hollering at my wife for her shortcomings. She left the house, 11 P.M. I’d quit drinking and smoking. She brought me back a bottle of rye and a pack of Luckies, too. I hadn’t smoked for two weeks. I must have been a horrible nuisance.

I took a drink and a smoke.

Then I was normal. My lungs and my liver cried out: At last, again! The old abuse! I am a confessed major organ beater. I should turn myself in on the hotline to normalcy.

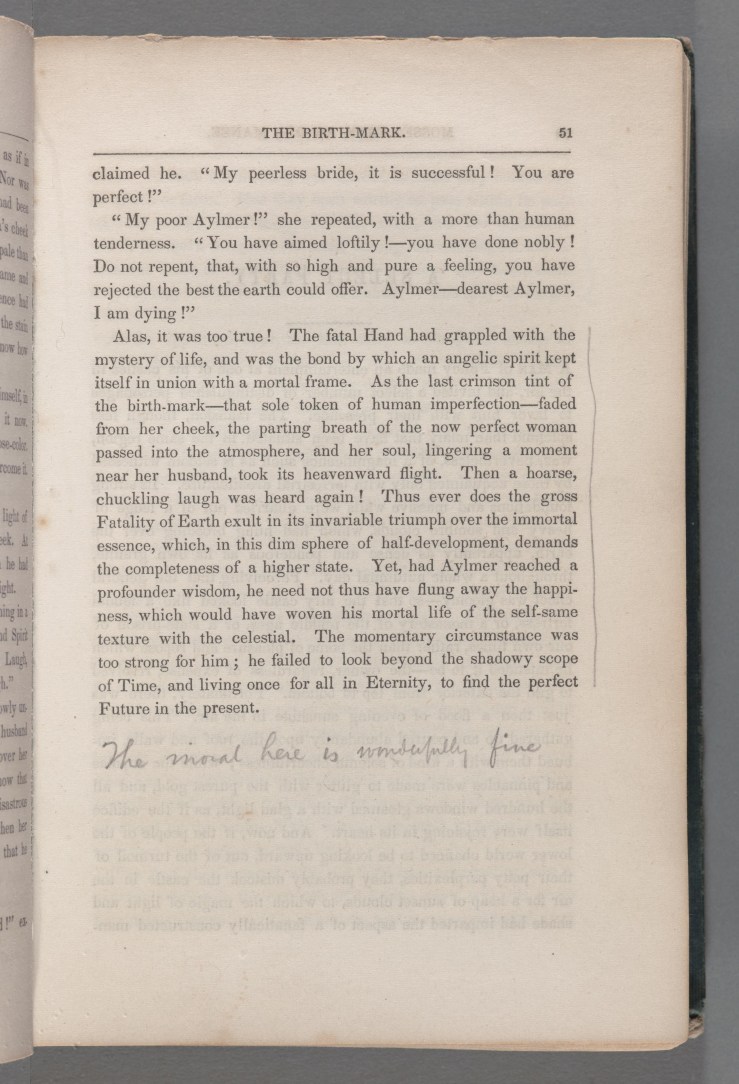

“The Moral Here Is Wonderfully Fine” — Melville Annotates Hawthorne

Herman Melville’s markings and annotations on the last page of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s short story “The Birth-mark.” From Melville’s Marginalia Online.

Book Shelves #15, 4.08.2012

1st Gent. How class your man? – as better than the most,

Or, seeming better, worse beneath that cloak?

As saint or knave, pilgrim or hypocrite?

2nd Gent. Nay, tell me how you class your wealth of books

The drifted relics of all time.

As well sort them at once by size and livery:

Vellum, tall copies, and the common calf

Will hardly cover more diversity

Than all your labels cunningly devised

To class your unread authors.

—George Eliot, Middlemarch, epigraph to Chapter 13

Book shelves series #15, fifteenth Sunday of 2012

A new book-case this week; the shorter triplet of the twin ladders seen here. What do the volumes on this top shelf hold in common? They are hardback. That’s about it. Yes, I actually go through The Riverside Shakespeare every now and then, especially when sparking new ideas for class lectures. The Balthus memoir is pretty good. No, I never finished Godel, Escher, Bach. It’s not hardback, come to think of it. The Fallada books are good stuff. Will Dylan ever finish up the Chronicles? Probably not. Maybe so. Who knows? We all love Shel Silverstein, of course.

“Little or No Love” — Nietzsche on Good and Bad Books

158. Little or no Love. —Every good book is written for a particular reader and men of his stamp, and for that very reason is looked upon unfavourably by all other readers, by the vast majority. Its reputation accordingly rests on a narrow basis and must be built up by degrees.—The mediocre and bad book is mediocre and bad because it seeks to please, and does please, a great number.

—Friedrich Nietzsche, Human, All Too Human, Part II.

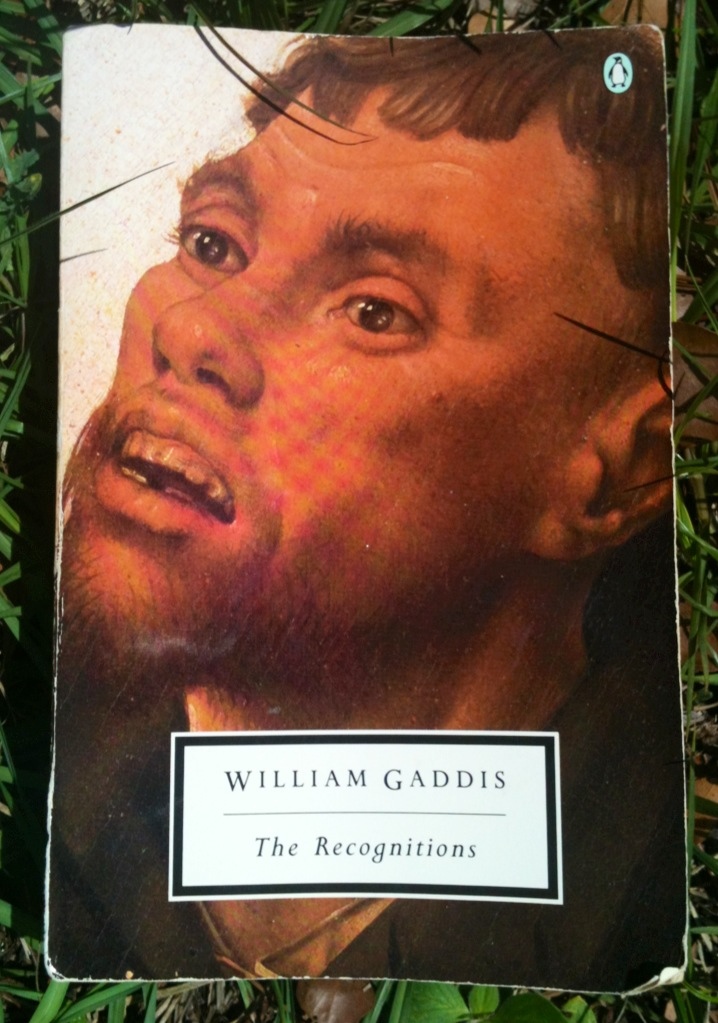

A Riff on William Gaddis’s The Recognitions

- I finished reading William Gaddis’s enormous opus The Recognitions a few days ago. I made a decent first attempt at the book in the summer of 2009, but wound up distracted not quite half way through, and eventually abandoned the book. I did, however, write about its first third. I will plunder occasionally from that write-up in this riff. Like here:

In William Gaddis‘s massive first novel, The Recognitions, Wyatt Gwyon forges paintings by master artists like Hieronymous Bosch, Hugo van der Goes, and Hans Memling. To be more accurate, Wyatt creates new paintings that perfectly replicate not just the style of the old masters, but also the spirit. After aging the pictures, he forges the artist’s signature, and at that point, the painting is no longer an original by Wyatt, but a “new” old original by a long-dead genius. The paintings of the particular artists that Wyatt counterfeits are instructive in understanding, or at least in hoping to understand how The Recognitions works. The paintings of Bosch, Memling, or Dierick Bouts function as highly-allusive tableaux, semiotic constructions that wed religion and mythology to art, genius, and a certain spectacular horror, and, as such, resist any hope of a complete and thorough analysis. Can you imagine, for example, trying to catalog and explain all of the discrete images in Bosch’s triptych, The Garden of Earthly Delights? And then, after creating such a catalog, explaining the intricate relationships between the different parts? You couldn’t, and Gaddis’s novel is the same way.

I still feel the anxiety dripping from that lede, the sense that The Recognitions might be a dare beyond my ken. Mellower now, I’m content to riff.

- I read this citation in Friedrich Nietzsche’s Human, All Too Human, Part II the other night, mentally noting, “cf. Gaddis”:

188. The Muses as Liars. —“We know how to tell many lies,” so sang the Muses once, when they revealed themselves to Hesiod.—The conception of the artist as deceiver, once grasped, leads to important discoveries.

- The Recognitions: crammed with poseurs and fakers, forgers and con-men, artists and would-be artists.

-

To recognize: To see and know again. Recognition entails time, experience, certitude, authenticity.

-

Who would not dogear or underline or highlight this passage?:

That romantic disease, originality, all around we see originality of incompetent idiots, they could draw nothing, paint nothing, just so the mess they make is original . . .

-

In many ways The Recognitions, or rather the characters in The Recognitions whom we might identify with genuine talent, genius, or spirit (to be clear, I’m thinking of Wyatt/Stephan, Basil Valentine, Stanley, Anselm, maybe, and Frank Sinisterra) are conservative, reactionary even; this is somewhat ironic considering Gaddis’s estimable literary innovations.

-

Esme: A focus for the novel’s masculine gaze, or a critique of such gazes?

-

The central problem of The Recognitions (perhaps): What confers meaning in a desacralized world?

Late in the novel, in one of its many party scenes, Stanley underlines the problem, working in part from Voltaire’s (in)famous quote that, “If there were no God, it would be necessary to invent him”:

. . . even Voltaire could see that some transcendent judgments is necessary, because nothing is self-sufficient, even art, and when art isn’t an expression of something higher, when it isn’t invested you might even say, it breaks up into fragments that don’t have any meaning . . .

Here we think of Wyatt: Wyatt who rejects the ministry, contemporary art, contemporary society, sanity . . .

- Wyatt’s quest: To find truth, meaning, authenticity in a modern world where the sacred does not, cannot exist, is smothered by commerce, noise, fakery . . .

The Recognitions conveys a range of tones, but I like it best when it focuses its energies on comic irony and dark absurdity to detail the juxtapositions and ironies between meaning and noise, authenticity and forgery.

(I like The Recognitions least when its bile flares up too much in its throat, when its black humor tips over into a screed of despair. A more mature Gaddis handles bitterness far better in JR, I think—but I parenthesize this note, as it seems minor even in a list of minor digressions).

Probably my favorite chapter of the book — after the very first chapter, which I believe can stand on its own — is Chapter V of Part II. This is the chapter where Frank Sinisterra reemerges, setting into motion a failed plan to disseminate his counterfeit money (“the queer,” as his accomplice calls it). We also meet Otto’s father, Mr. Pivner, a truly pathetic figure (in all senses of the word). This chapter probably contains more immediate or apparent action than any other in The Recognitions, which largely relies on implication (or suspended reference).

More on Part II, Chapter V: Here we find a savagely satirical and very funny discussion of Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People, a book that seems to stand as an emblem (one of many in The Recognitions) of the degraded commercial world that Gaddis repeatedly attacks. The entire discussion of Carnegie’s book is priceless — it begins on page 497 of my Penguin edition and unfurls over roughly 10 pages—and the book is alluded to enough in The Recognitions to become a motif.

I’ll quote from page 499 a passage that seems to ironically situate How to Win Friends and Influence People against The Recognitions itself (this is one of the many postmodern moves of the novel):

It was written with reassuring felicity. There were no abstrusely long sentences, no confounding long words, no bewildering metaphors in an obfuscated system such as he feared finding in simply bound books of thoughts and ideas. No dictionary was necessary to understand its message; no reason to know what Kapila saw when he looked heavenward, and of what the Athenians accused Anaxagoras, or to know the secret name Jahveh, or who cleft the Gordian knot, the meaning of 666. There was, finally, very little need to know anything at all, except how to “deal with people.” College, the author implied, meant simply years wasted on Latin verbs and calculus. Vergil, and Harvard, were cited regularly with an uncomfortable, if off-hand, reverence for their unnecessary existences . . . In these pages, he was assured that whatever his work, knowledge of it was infinitely less important that knowing how to “deal with people.” This was what brought a price in the market place; and what else could anyone possibly want?

- I’m not sure if Gaddis is ahead of his time or of his time in the above citation.

The Recognitions though, on the whole, feels more reactionary than does his later novel JR, which is so predictive of our contemporary society as to produce a maddening sense of the uncanny in its reader.

- Even more on Part II, Chapter V (which I seem to be using to alleviate the anxiety of having to account for so many of the book’s threads): Here we find a delineation of (then complication of, then shuffling of) the various father-son pairings and substitutions that will play out in the text. (Namely, the series of displacements between Pivner, Otto, and Sinisterra, with the subtle foreshadowing of Wyatt’s later (failed) father-son/mentor-pupil relationship with Sinisterra).

Is it worth pointing out that the father-son displacements throughout the text are reminiscent of Joyce’s Ulysses, a book that Gaddis pointedly denied as an influence?

Ignorant of Gaddis’s deflections, I wrote the following in my review almost three years ago:

Gaddis shows a heavy debt to James Joyce‘s innovations in Ulysses here (and throughout the book, of course), although it would be a mistake to reduce the novel to a mere aping of that great work. Rather, The Recognitions seems to continue that High Modernist project, and, arguably, connect it to the (post)modern work of Pynchon, DeLillo, and David Foster Wallace. (In it’s heavy erudition, numerous allusions, and complex voices, the novel readily recalls both W.G. Sebald and Roberto Bolaño as far as I’m concerned).

- But, hey, Cynthia Ozick found Joyce’s mark on The Recognitions as well (from her 1985 New York Times review of Carpenter’s Gothic):

When ”The Recognitions” arrived on the scene, it was already too late for those large acts of literary power ambition used to be good for. Joyce had come and gone. Imperially equipped for masterliness in range, language and ironic penetration, born to wrest out a modernist masterpiece but born untimely, Mr. Gaddis nonetheless took a long draught of Joyce’s advice and responded with surge after surge of virtuoso cunning.

- We are not obligated to listen to Gaddis’s denials of a Joyce influence, of course. When asked in his Paris Review interview if he’d like to clarify anything about his personality and work, he paraphrases his novel:

I’d go back to The Recognitions where Wyatt asks what people want from the man they didn’t get from his work, because presumably that’s where he’s tried to distill this “life and personality and views” you speak of. What’s any artist but the dregs of his work: I gave that line to Wyatt thirty-odd years ago and as far as I’m concerned it’s still valid.

- And so Nietzsche again, again from Human, All Too Human, Part II:

140. Shutting One’s Mouth. —When his book opens its mouth, the author must shut his.

- And if I’m going to quote German aphorists, here’s a Goethe citation (from Maxims and Reflections) that illustrates something of the spirit of The Recognitions:

There is nothing worth thinking but it has been thought before; we must only try to think it again.

- And if I’m going to quote Goethe, I’ll also point out then that Gaddis began The Recognitions as a parody of Goethe’s Faust. Peter William Koenig writes in his excellent and definitive essay “Recognizing Gaddis’ Recognitions” (published in the Winter Volume Contemporary Literature, 1975):

To understand Gaddis’ relationship to his characters, and thus his philosophical motive in writing the novel, we are helped by knowing how Gaddis conceived of it originally. The Recognitions began as a much smaller and less complicated work, passing through a major evolutionary stage during the seven years Gaddis spent writing it. Gaddis says in his notes: “When I started this thing . . . it was to be a good deal shorter, and quite explicitly a parody on the FAUST story, except the artist taking the place of the learned doctor.” Gaddis later explained that Wyatt was to have all talent as Faust had all knowledge, yet not be able to find what was worth doing. This plight-of limitless talent, limited by the age in which it lives-was experienced by an actual painter of the late 1940s, Hans Van Meegeren, on whom Gaddis may have modeled Wyatt. The authorities threw Van Meegeren into jail for forging Dutch Renaissance masterpieces, but like Wyatt, his forgeries seemed so inspired and “authentic” that when he confessed, he was not believed, and had to prove that he had painted them. Like Faust and Wyatt, Van Meegeren seemed to be a man of immense talent, but no genius for finding his own salvation.

The Faust parody remained uppermost in Gaddis’ mind as he traveled from New York to Mexico, Panama and through Central America in 1947, until roughly the time he reached Spain in 1948. Here Gaddis read James Frazer’s The Golden Bough, and the novel entered its second major stage. Frazer’s pioneering anthropological work demonstrates how religions spring from earlier myths, fitting perfectly with Gaddis’ idea of the modern world as a counterfeit-or possibly inspiring it. In any case, Frazer led Gaddis to discover that Goethe’s Faust originally derived from the Clementine Recognitions, a rambling third-century theological tract of unknown authorship, dealing with Clement’s life and search for salvation. Gaddis adapted the title, broadening the conception of his novel to the story of a wandering, at times misguided hero, whose search for salvation would record the multifarious borrowings and counterfeits of modern culture.

- Is Wyatt the hero of The Recognitions? Here’s Basil Valentine (page 247 of my ed.):

. . . that is why people read novels, to identify projections of their own unconscious. The hero has to be fearfully real, to convince them of their own reality, which they rather doubt. A novel without a hero would be distracting in the extreme. They have to know what you think, or good heavens, how can they know that you’re going through some wild conflict, which is after all the duty of a hero.

- If Wyatt is the hero, then what is Otto? Clearly Otto is a comedic double of some kind for Wyatt, a would-be Wyatt, a different kind of failure . . . but is he a hero?

When I first tried The Recognitions I held Otto in special contempt (from that earlier review of mine):

Otto follows Wyatt around like a puppy, writing down whatever he says, absorbing whatever he can from him, and eventually sleeping with his wife. Otto is the worst kind of poseur; he travels to Central America to finish his play only to lend the mediocre (at best) work some authenticity, or at least buzz. He fakes an injury and cultivates a wild appearance he hopes will give him artistic mystique among the Bohemian Greenwich Villagers he hopes to impress. In the fifth chapter, at an art-party, Otto, and the reader, learn quickly that no one cares about his play . . .

But a full reading of The Recognitions shows more to Otto besides the initial anxious shallowness; Gaddis allows him authentic suffering and loss. (Alternately, my late sympathies for Otto may derive from the recognition that I am more of an Otto than a Wyatt . . .).

- The Recognitions is the work of a young man (“I think first it was that towering kind of confidence of being quite young, that one can do anything,” Gaddis says in his Paris Review interview), and often the novel reveals a cockiness, a self-assurance that tips over into didactic essaying or a sharpness toward its subjects that neglects to account for any kind of humanity behind what Gaddis attacks. The Recognitions likes to remind you that its erudition is likely beyond yours, that it’s smarter than you, even as it scathingly satirizes this position.

I think that JR, a more mature work, does a finer job in its critique of contemporary America, or at least in its characterization of contemporary Americans (I find more spirit or authentic humanity in Bast and Gibbs and JR than in Otto or Wyatt or Stanley). This is not meant to be a knock on The Recognitions; I just found JR more balanced and less showy; it seems to me to be the work of an author at the height of his powers, if you’ll forgive the cliché.

I’ll finish this riff-point by quoting Gaddis from The Paris Review again:

Well, I almost think that if I’d gotten the Nobel Prize when The Recognitions was published I wouldn’t have been terribly surprised. I mean that’s the grand intoxication of youth, or what’s a heaven for.

(By the way, Icelandic writer Halldór Kiljan Laxness won the Nobel in lit in 1955 when The Recognitions was published).

- Looking over this riff, I see it’s lengthy, long on outside citations and short on plot summary or recommendations. Because I don’t think I’ve made a direct appeal to readers who may be daunted by the size or reputation or scope of The Recognitions, let me be clear: While this isn’t a book for everyone, anyone who wants to read it can and should. As a kind of shorthand, it fits (“fit” is not the right verb) in that messy space between modernism and postmodernism, post-Joyce and pre-Pynchon, and Gaddis has a style and approach that anticipates David Foster Wallace. (It’s likely that if you made it this far into the riff that you already know this or, even more likely, that you realize that these literary-historical situations mean little or nothing).

26.Very highly recommended.