We often identify genre simply by its conventions and tropes, and, when October rolls round and we want scary stories, we look for vampires and haunted houses and psycho killers and such. And while there’s plenty of great stuff that adheres to the standard conventions of horror (Lovecraft and Poe come immediately to mind) let’s not overlook novels that offer horror just as keen as any genre exercise. We offer seven horror novels masquerading in other genres:

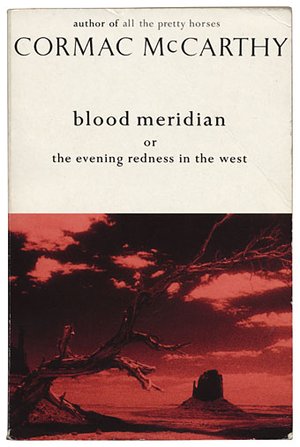

Blood Meridian — Cormac McCarthy

In our review (link above) we called Blood Meridian “a blood-soaked, bloodthirsty bastard of a book.” The story of the Glanton gang’s insane rampage across Mexico and the American Southwest in the 1850s is pure horror. Rape, scalping, dead mules, etc. And Judge Holden. . . [shivers].

Rushing to Paradise — J.G. Ballard

On the surface, Ballard’s 1994 novel Rushing to Paradise seems to be a parable about the hubris of ecological extremism that would eliminate humanity from any natural equation. Dr. Barbara and her band of misfit environmentalists try to “save” the island of St. Esprit from France’s nuclear tests. The group eventually begin living in a cult-like society with Dr. Barbara as its psycho-shaman center. As Dr. Barbara’s anti-humanism comes to outweigh any other value, the island devolves into Lord of the Flies insanity. Wait, should Lord of the Flies be on this list?

Okay. We know. This book ends up on every list we write. What can we do?

While there’s humor and pathos and love and redemption in Bolaño’s masterwork, the longest section of the book, “The Part about the Crimes,” is an unrelenting catalog of vile rapes, murders, and mutilations that remain unresolved. The sinister foreboding of 2666‘s narrative heart overlaps into all of its sections (as well as other Bolaño books); part of the tension in the book–and what makes Bolaño such a gifted writer–is the visceral tension we experience when reading even the simplest incidents. In the world of 2666, a banal episode like checking into a motel or checking the answering machine becomes loaded with Lynchian dread. Great horrific stuff.

King Lear — William Shakespeare

Macbeth gets all the propers as Shakespeare’s great work of terror (and surely it deserves them). But Lear doesn’t need to dip into the stock and store of the supernatural to achieve its horror. Instead, Shakespeare crafts his terror at the familial level. What would you do if your ungrateful kids humiliated you and left you homeless on the heath? Go a little crazy, perhaps? And while Lear’s daughters Goneril and Regan are pure mean evil, few characters in Shakespeare’s oeuvre are as crafty and conniving as Edmund, the bastard son of Glouscester. And, lest we forget to mention, Lear features shit-eating, self-mutilation, a grisly tableaux of corpses, and an eye-gouging accompanied by one of the Bard’s most enduring lines: “Out vile jelly!” Peter Brook chooses to elide the gore in his staging of that infamous scene:

The Trial — Franz Kafka

Kafka captured the essential alienation of the modern world so well that we not only awarded him his own adjective, we also tend to forget how scary his stories are in light, perhaps, of their absurd familiarity. For our money, none surpasses his unfinished novel The Trial, the story of hapless Josef K., a bank clerk arrested by unknown agents for an unspecified crime. While much of K.’s attempt to figure out just who is charging him for what is hilarious in its absurdity, its also deeply dark and really creepy. K. attempts to find some measure of agency in his life, but is ultimately thwarted by forces he can’t comprehend–or even see for that matter. Nowhere is this best expressed than in the famous “Before the Law” episode. If you’re too lazy to read it, check out his animation with narration by the incomparable Orson Welles:

In our original review of Sanctuary (link above), we noted that “if you’re into elliptical and confusing depictions of violence, drunken debauchery, creepy voyeurism, and post-lynching sodomy, Sanctuary just might be the book for you.” There’s also a corn-cob rape scene. The novel is about the kidnapping and debauching of Southern belle Temple Drake by the creepy gangster Popeye–and her (maybe) loving every minute of it. The book is totally gross. We got off to a slow start with Faulkner. If you take the time to read our full review above (in which we make some unkind claims) please check out our retraction. In retrospect, Sanctuary is a proto-Lynchian creepfest, and one of the few books we’ve read that has conveyed a total (and nihilistic) sense of ickyness.

Great Apes — Will Self

Speaking of ickiness…Self’s 1997 novel Great Apes made me totally sick. Nothing repulses me more than images of chimpanzees dressed as humans and Great Apes is the literary equivalent (just look at that cover). After a night of binging on coke and ecstasy, artist Simon Dykes wakes up to find himself in a world where humans and apes have switched roles. Psychoanalysis ensues. While the novel is in part a lovely satire of emerging 21st-century mores, its humor doesn’t outweigh its nightmare grotesquerie. Great Apes so deeply affected us that we haven’t read any of Self’s work since.

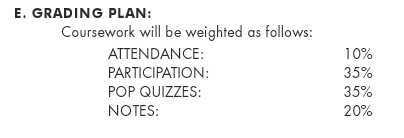

We’re pretty sure the grading plan is fairly tongue in cheek, but the lectures might be fun, and perhaps might contain something a bit more substantial than the average, uh, tweet (ugh). More at

We’re pretty sure the grading plan is fairly tongue in cheek, but the lectures might be fun, and perhaps might contain something a bit more substantial than the average, uh, tweet (ugh). More at