My family and I took our Florida asses to the West Coast for a wonderful week earlier this month. We flew into LA, stayed in Santa Monica for a few days and nights, riding bikes up and down the beautiful coast and visiting proximal neighborhoods. We later drove east to Joshua Tree, where we stayed in a lovely little house for a few days, visiting the National Park as well as nearby towns and sites, like Twentynine Palms, Palm Springs, and Mt. San Jacinto State Park. We saw coyotes and roadrunners and lots of little desert cottontails. Famous times.

While in Santa Monica, I could not convince my family (or frankly myself) to trek the hour or so south to visit Thomas Pynchon’s old apartment in Manhattan Beach. We did, however, stop by Small World Books in Venice Beach. Small World is right across from the Venice Beach Skatepark, where we watched kids of all ages skate for almost an hour while someone blasted nineties hip-hop from a boombox (one of the nicest hours of the trip for me).

Small World is a well-stocked bookshop with an emphasis on literature and the arts; it carries plenty of indie titles and a handsome stable of standards. There was a nice cat in there too. Founded in 1969 by Mildred Gates and Mary Goodfader, Small World seems to retain some of the older vibes of Venice Beach, which is generally pretty touristy (in a fun, tacky way). It seems a bit out of place among the keychains and bad art and nasty tee shirts of Venice, what with its stock of NYRB translations, poetry zines, and novels by indie imprints like And Other Stories. But it’s clear that locals come to buy books there.

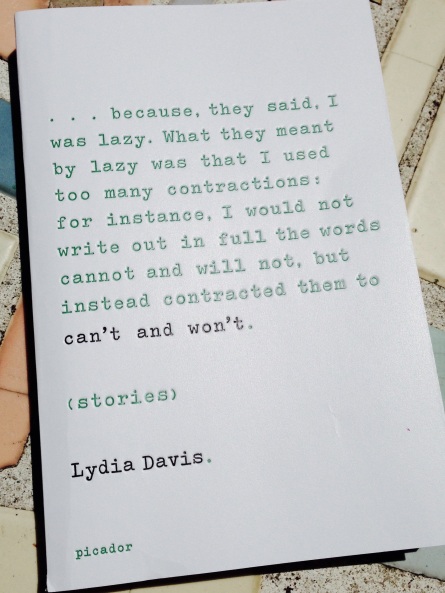

I picked up three: Lydia Davis’s Our Strangers, June-Alison Gibbons’s The Pepsi-Cola Addict, and Ann Quin’s Three. I’d been looking to buy Davis’s collection for a while now–you can buy it online, but I wanted to get it from an indie bookshop, per Davis’s intentions. Three is the only Ann Quin book I haven’t read yet; I loved her novels Berg and Passages, and I guess I wanted to leave something in the Quin take for later. The highlight purchase though for me has been Gibbons’s The Pepsi-Cola Addict, which was Small World’s featured book (I think they did a book club on it this month). I had never heard of the book or its author, but the pop art cover and goofy title caught my attention, followed by an even goofier blurb which started by describing the Pepsi-Cola Addict as the “legendary lost novel in which fourteen-year-old Preston Wildey-King must choose between his all-consuming passion for Pepsi Cola and his love for schoolmate Peggy.” The novel is not goofy though—it’s abject and odd and distressing and also very well-written, somehow naive and sophisticated, raw and refined, resoundingly truthful and plainly artificial. Here’s the full blurb:

Written by June-Alison Gibbons when she was only 16, The Pepsi Cola Addict is considered one of the great works of twentieth-century outsider literature. More than just a literary curiosity, however, this tale of a teenager whose passion for a well-known cola drink threatens to ruin his life is the uniquely vivid expression of a young woman trying to make sense of the confusing, often brutal world she in which found herself.

Published in 1982 by a vanity press who took £500 from its young author and gave her only a single book in return, it’s thought that fewer than ten original copies still exist in the world.

Shortly after its publication, June-Alison and her sister Jennifer would become infamous as “The Silent Twins” and find themselves cruelly incarcerated for over a decade in Broadmoor Hospital. This author-approved edition makes June-Alison Gibbon’s remarkable vision widely available for the first time.

I hope to have a full review to come. I read The Pepsi-Cola Addict in Joshua Tree and absolutely loved it (even though (and I guess because) it made me feel odd and ill).

Unfortunately, I didn’t make it to Angel City Books & Records in Santa Monica. I had also wanted to visit Space Cowboy Books in Joshua Tree, but didn’t realize it was closed midweek. I did drop by The Best Bookstore in Palm Springs, and was again pleasantly surprised by the rich stock of titles, which eschewed the bestseller list stuff I might have expected for a somewhat touristy area. My son conned me into buying him a Taschen volume of Michelangelo drawings and studies; he’s been copying them into his notebooks for days now.

We loved Joshua Tree (park and city), and one highlight was the Noah Purifoy Outdoor Museum, a loose, sprawling collection of sculptures, installations, and buildings cobbled together out of the detritus of the twentieth century. Walking through the Museum is kind of like being on the disused set of a post-apocalyptic film, under the beautiful clear California sun filled sky. Cottontails and roadrunners hopped about as we wandered among Purifoy’s deconstructed constructions, sometimes apprehensive to enter or touch, before the sun and wind and arid sky itself reminded us that the whole tableau was naked, exposed, raw on the earth, open for contact.

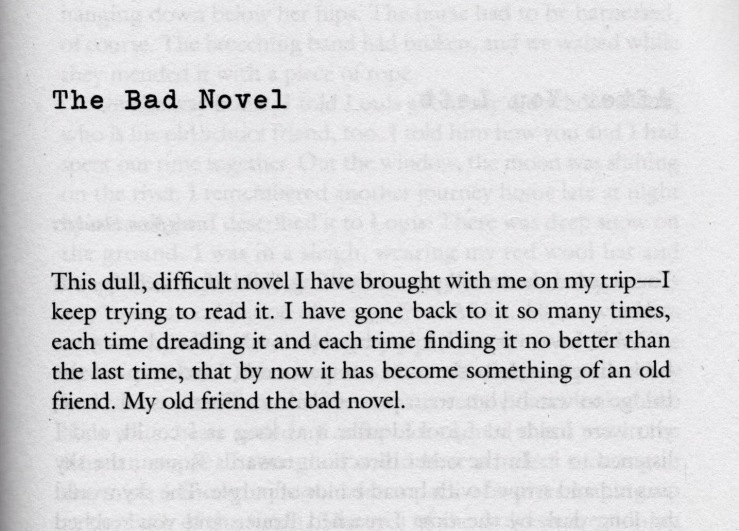

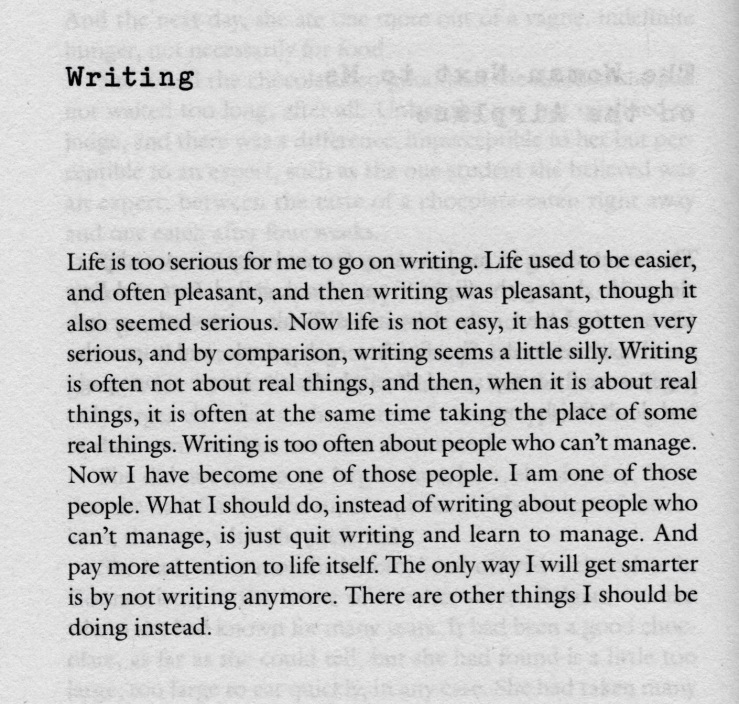

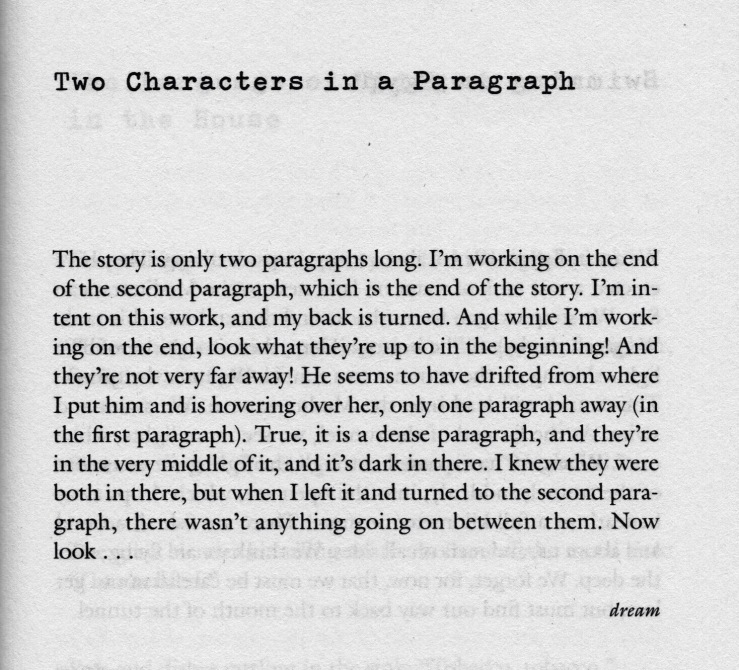

Almost finished with this bad boy, or as “finished” as one can be with Davis’s stuff, which I tend to linger on, return to. Full review forthcoming.

Almost finished with this bad boy, or as “finished” as one can be with Davis’s stuff, which I tend to linger on, return to. Full review forthcoming.