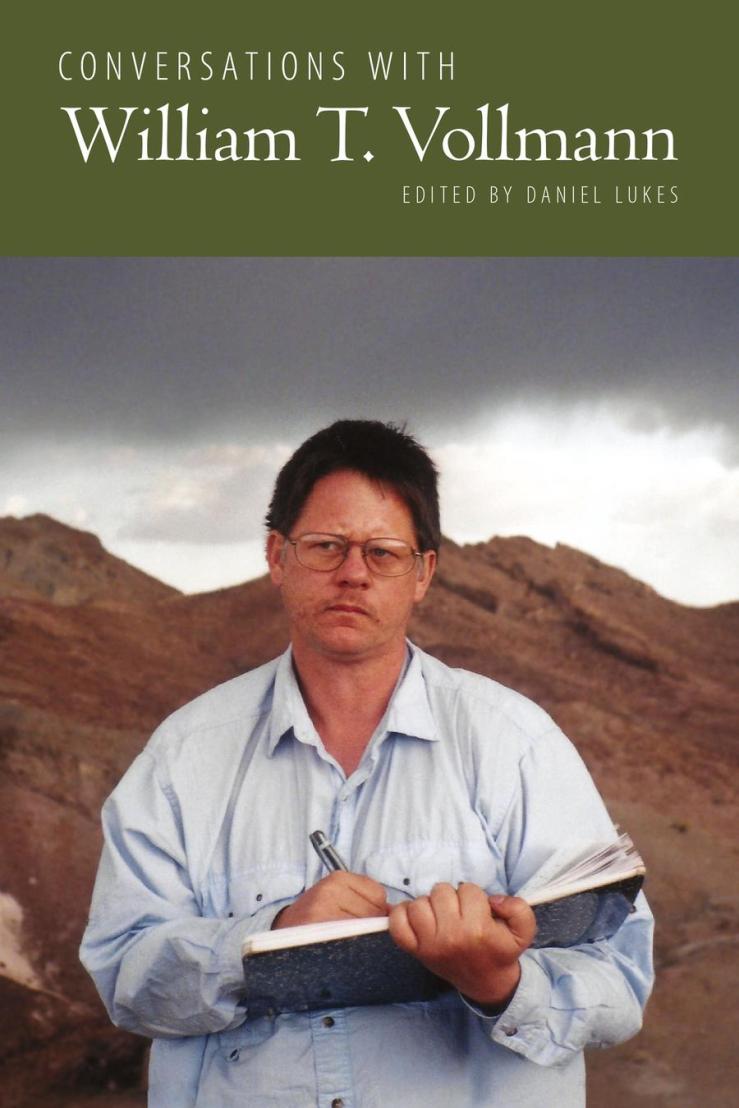

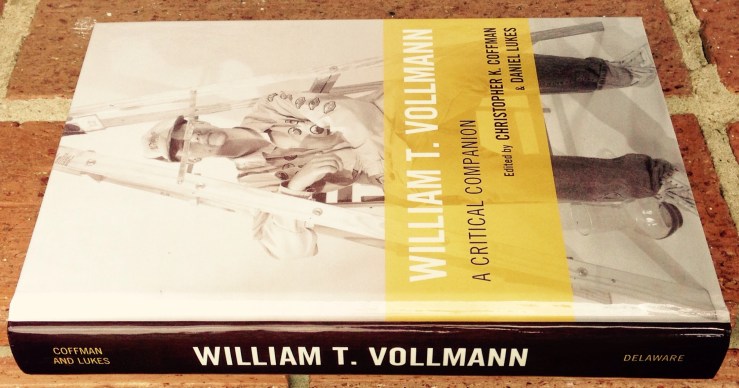

William T. Vollmann: A Critical Companion, new from University of Delaware Press, collects academic essays and memoir-vignettes by a range of critics and authors to make the case that Vollmann is, as the blurb claims, the “most ambitious, productive, and important living author in the US.” I interviewed the book’s editors, Christopher K. Coffman and Daniel Lukes, over a series of emails.

If you live in NYC (or feel like traveling), you can check out the book launch for William T. Vollmann: A Critical Companion this weekend, hosted by Coffman and Lukes (4:30pm at the 11th Street Bar).

This is the first part of a two-part interview.

Biblioklept: How did William T. Vollmann: A Critical Companion come about?

Daniel Lukes: The starting point would be the MLA panel I put together in January 2011, called “William T. Vollmann: Methodologies and Morals.” Chris’s was the first abstract I received and I remember being impressed with its confidence of vision. Michael Hemmingson also gave a paper, and Larry McCaffery was kind enough to act as respondent. Joshua Jensen was also a panelist. I kept in touch with Chris and we very soon decided that there was a hole in the market, so to speak, so we put out a call for papers and took it from there.

One of my favorite things about putting together this book has been connecting with – and being exposed to – such a range of perspectives on Vollmann: people seem to come at him from – and find in his works – so many different angles. It’s bewildering and thrilling to talk about the same author with someone and not quite believe you are doing so. And I think this started for me, in a way, at least as far as this book is concerned, with reading Chris’ MLA abstract.

Biblioklept: I first heard about Vollmann in connection to David Foster Wallace (Wallace namechecks him in his essay “A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again”). A friend “loaned” me his copy of The Ice-Shirt and I never gave it back. When was the first time you read Vollmann?

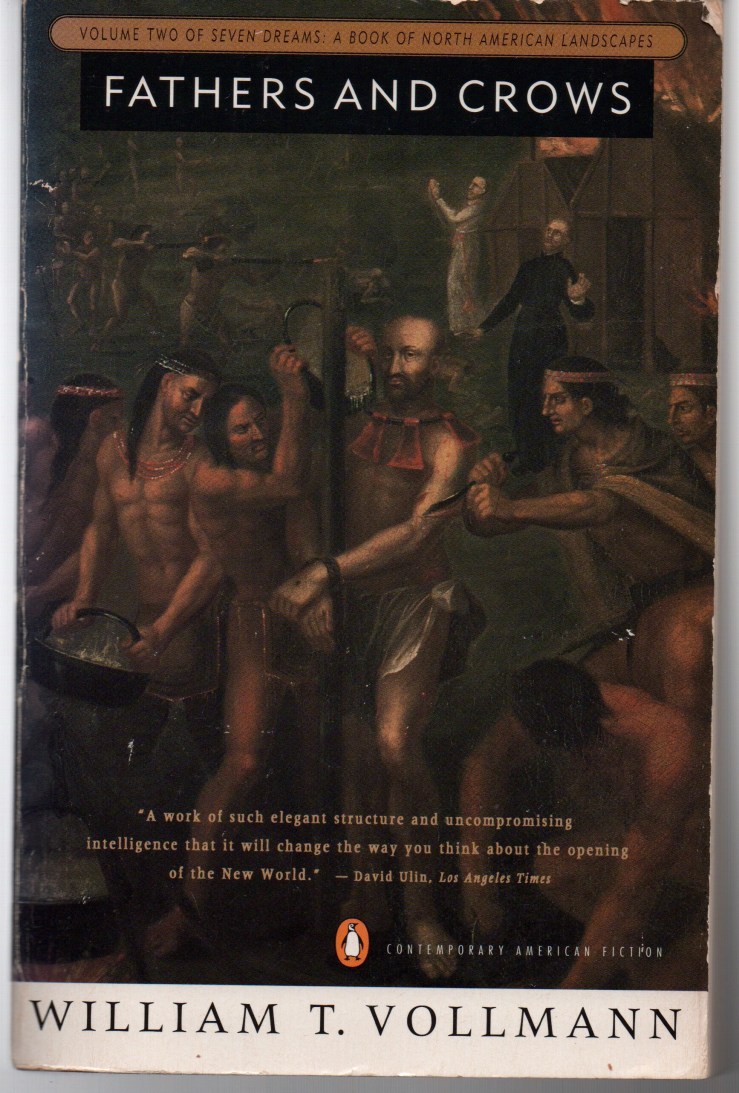

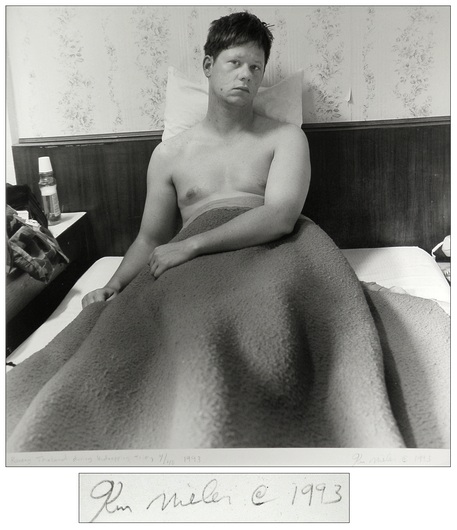

Christopher K. Coffman: I first encountered William T. Vollmann’s work about ten years ago. At the time, I had just finished grad school, and as my dissertation work had been focused on aspects of modern and contemporary poetry, I had let my attention to contemporary prose slip a bit. When I realized this had happened, I starting reading a lot of recent fiction. Of course David Foster Wallace’s books were part of this effort, and I, like so many others, really developed a love for Infinite Jest and some of the stories in Girl with Curious Hair. My memory’s a bit fuzzy on the timeline, but my best guess, given what I know I was reading and thinking about at the time, is that in my reading around DFW I discovered the Summer 1993 issue of The Review of Contemporary Fiction with which Larry McCaffery had been involved, and that the interview with DFW in that issue–along with the WTV materials themselves–woke me up to WTV and his work. I can’t say enough about how important Larry’s championing of WTV has been, and continues to be. Of course, one could say that about his support for so many of the interesting things that have happened in fiction during the past three or four decades. His interviews, his editorial work, the part he played with the Fiction Collective …. the list of the ways that he identifies and promotes some of the best work out there could go on for a while, and no one else that I know of has done it as well as Larry has for as long as he has. Anyway, as I was pretty much broke at the time, my reading choices were governed in large part by what I could find at libraries or local used bookstores, and The Ice-Shirt was the first volume I came across in one of these venues. I was already a huge fan of The Sot-Weed Factor and Mason & Dixon, and the entire Seven Dreams project very much struck me as a next step forward along the trajectory those books described. As a consequence, I immediately started tracking down and reading not only the rest of the Dreams, but also everything else I could find by WTV.

What about The Ice-Shirt that really won me over, aside from my impression that this was another brilliant reinterpretation of the historical novel, is that WTV was clearly bringing together and pushing to their limits some of my favorite characteristics of post-1945 American fiction (structural hijinks of a sort familiar from works by figures like Barth and Barthelme, a fearlessness in terms of subject matter and the occasional emergence of a vatic tone that reminded me of Burroughs, an autofictional element of the sort you see in Hunter S. Thompson). Furthermore, as a literary critic, I was really intrigued by two additional aspects of the text: the degree to which The Ice-Shirt foregrounds the many ways that it is itself an extended interpretation of earlier texts (the sagas on which he draws for many of the novel’s characters and much of its action), and the inclusion of extensive paratexts–the notes, glossaries, timelines, and so forth. In short, this seemed like a book that united my favorite characteristics of contemporary literary fiction with a dedication to the sort of work that I, as a scholar, spend a lot of my time doing. How could I resist? It took my readings of a few more of WTV’s books for me to be able to recognize what I would argue are his other most significant characteristics: his global scope and his deep moral vision.

As for your also having begun reading WTV with The Ice-Shirt: It’s an interesting coincidence to me that we both started with that book. I have always assumed that most people start into WTV via either the prostitute writings (which have a sort of underground cachet by virtue of subject matter) or Europe Central (which is of course the book that got the most mainstream attention), but here we both are with The Ice-Shirt. WTV has indicated he sees it as under-realized in certain ways, but I am still quite fond of it, even in comparison to some of the later books. Continue reading “An Interview with Christopher K. Coffman and Daniel Lukes, Editors of William T. Vollmann: A Critical Companion (Part I)” →