Zero, Ignácio de Loyola Brandão. Translated by Ellen Watson. Avon Bard (1983). No cover artist or designer credited. 317 pages.

A very strange fragmentary hallucinatory novel. A few pages:

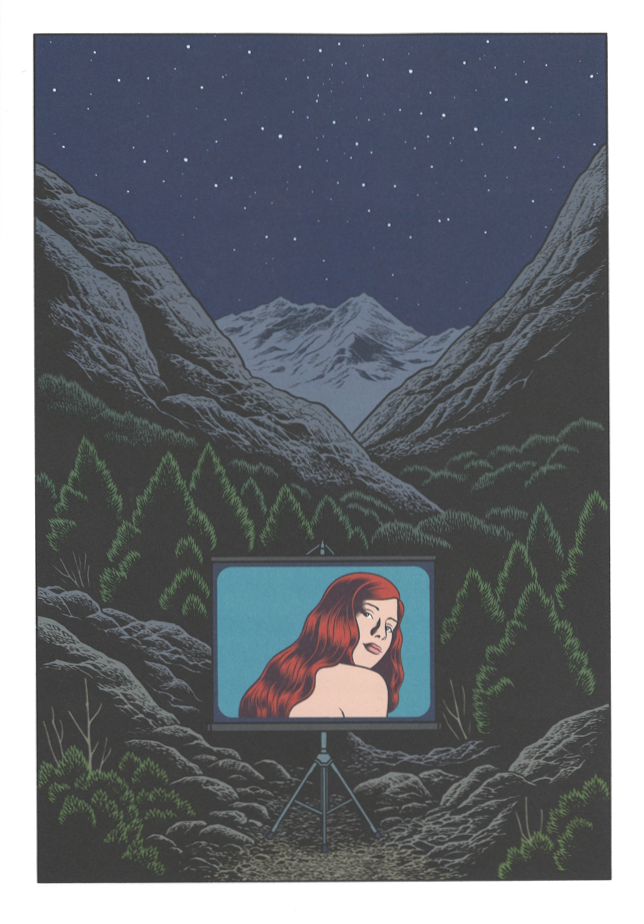

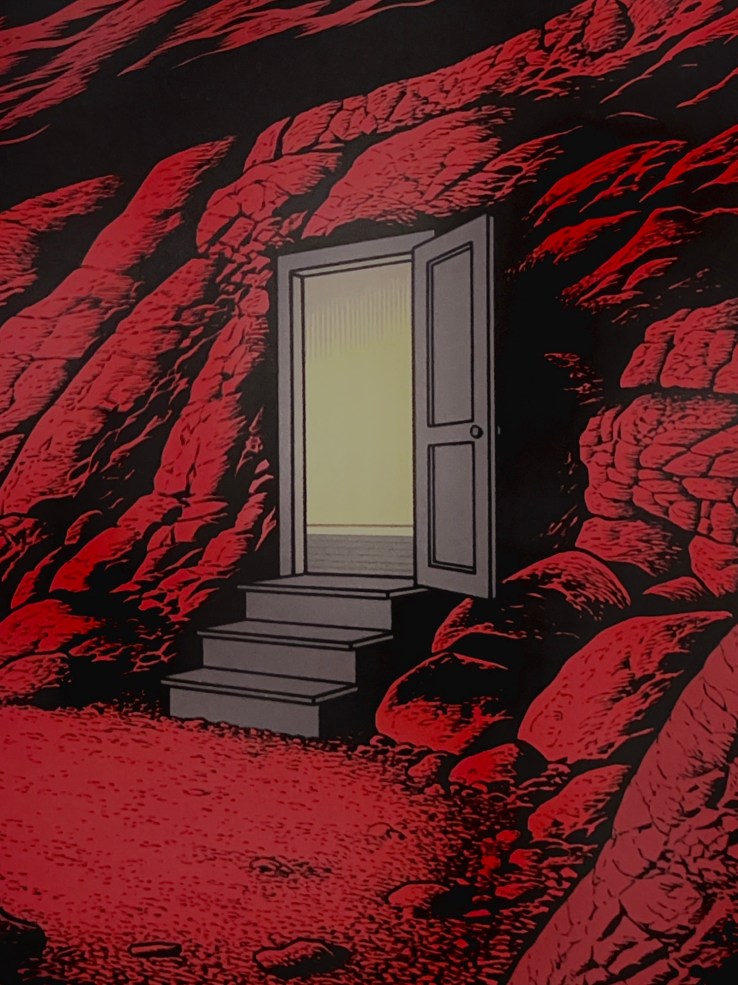

Charles Burns’ latest graphic novel Final Cut tells the story of Brian, an obsessive would-be auteur grappling with an unrealized film project. Brian hopes to assemble his film — also titled Final Cut — from footage he shoots with friends on a weekend camping trip, but the messiness of reality impinges the weird glories of his vibrant imagination. He cannot bring his vision to the screen. He cannot capture all the “fucked-up shit going on inside my head.”

Charles Burns’ latest graphic novel Final Cut tells the story of Brian, an obsessive would-be auteur grappling with an unrealized film project. Brian hopes to assemble his film — also titled Final Cut — from footage he shoots with friends on a weekend camping trip, but the messiness of reality impinges the weird glories of his vibrant imagination. He cannot bring his vision to the screen. He cannot capture all the “fucked-up shit going on inside my head.”

Capturing all the fucked-up shit going on inside my head is a neat encapsulation of the Artistic Problem in general. It’s not that Brian doesn’t try; if anything, he tries too hard. His best friend and erstwhile cameraman Chris is there to help him, along with his crush Laurie and their friend Tina—but ultimately, these are still kids at play. They indulge Brian’s artistic whims, but at a certain point they’d rather swim, drink, and smoke than shoot yet another scene they can’t comprehend.

Capturing all the fucked-up shit going on inside my head is a neat encapsulation of the Artistic Problem in general. It’s not that Brian doesn’t try; if anything, he tries too hard. His best friend and erstwhile cameraman Chris is there to help him, along with his crush Laurie and their friend Tina—but ultimately, these are still kids at play. They indulge Brian’s artistic whims, but at a certain point they’d rather swim, drink, and smoke than shoot yet another scene they can’t comprehend.

Eschewing straightforward narrative conventions, Final Cut unfolds in a blend of flashbacks, dreamscapes, and flights into Brian’s imagination. The book also gives over to Laurie’s consciousness, providing an essential ballast of realism to anchor Brian’s (and Burns’, I suppose) surrealism. Brian would have Laurie as his muse, trying to capture her in his sketchbook, in his film, and in the intense gaze of his mind’s eye. And while Laurie is fascinated by Brian’s visions, she doesn’t understand them.

The last member of Brian’s would-be acting troupe is Tina, an earthy, funny gal who drinks a bit too much. She plays foil to Brian’s ambitions; her animated spirit punctures the seriousness of his film shoot. Again, these are just kids in the woods with a camera and camping gear.

And the film itself? Well, it’s about kids camping in the woods. And an alien invasion. And pod people.

The pod-people motif dominates Final Cut. We get the teens in their larval sleeping bags, transformed into aliens in their cocoons (echoed again in Brian’s imagination and in his sketches). The motif looms larger: Can we really know who a person is? Could they be someone else entirely? Can we really ever know all the fucked-up shit going on inside their head?

Indeed, Don Siegel’s 1956 film Invasion of the Body Snatchers is a major progenitor text for Final Cut. Brian even takes Laurie on a date to a screening of Invasion; he’s so mesmerized by the film that he weeps. Burns renders stills from the film in heavy chiaroscuro black and white, contrasting with the vibrant reds, maroons, and pinks that reverberate through the novel.

Burns recreates stills from another black and white film, Peter Bogdanovich’s 1971 coming-of-age heartbreaker The Last Picture Show. Again, Brian is obsessed with the film—or by the film, perhaps. In particular, he’s infatuated with Cybill Shepherd’s Jacy, whose character he imaginatively merges with his conception of Laurie.

While Invasion of the Body Snatchers is a science-fiction horror film, a deep sense of reality-soaked dread underpins it; The Last Picture Show is utterly real in its evocations of the emotional and physical lives of teenagers. Both films convey a maturity and balance of the fantastic with the real that Brian has not yet purchased via his own experiences, his own failures and heartbreaks.

The maturity and balance that Brian can imagine but not execute in his Final Cut is precisely the maturity and balance that Burns achieves in his Final Cut. Simply put, Final Cut is the effort of a master performing at the heights of his power, rendered with inspired technical proficiency. It delivers on themes Burns has been exploring from the earliest days of his career.

There’s the paranoia and alienation of adolescence Burns crafted in Black Hole, here delivered in a more vibrant, cohesive, and frankly wiser book. There’s the hallucinatory trauma and repression he conveyed in the X’ed Out trilogy (collected a decade ago as Last Look, the title of which prefigures Final Cut). There’s also an absence of parental authority here, a trope that Burns has deployed since 1991’s Curse of the Molemen. (In Final Cut, Brian’s mentally-unstable mother is a dead-ringer for Mrs. Pinkster, the domestic abuse victim rescued by the child-hero of Curse of the Molemen). There’s all the sinister dread and awful beauty that anyone following Burns’ career would expect, synthesized into his most lucid exploration of the inherent problems of artistic expression.

Ultimately, in Final Cut Charles Burns crafts a portrait of the artist as a weird young man. Brian wrestles with the friction sparked from his vital imagination butting up against cold reality. His ambitious unfinished film mirrors his own incomplete journey as an artist, highlighting the clash between youthful creative fervor and the inevitable constraints of life, experience, and maturity. Burns’ themes of alienation and artistic ambition may be familiar, but Final Cut feels fresh and vibrant, the culmination of the artist’s own entanglements with the irreality of reality. Highly recommended.

. ; , ; ; , , , . , , ; , – , . ; , ; , . ; , , ; . ” ‘ , ” : ” . ” , . , , . . ; , – . – ; ‘ . ; , , , . , . , , – . , , . , , . , , , , , . – . , . , , ; , . , , , ; , – , , . , ; . ; , ; , . , , . ; ; ; , . . – ; , . ” ? ” ; , ” , ” , ” . ” ” ? ” . , , ” ? ” ” , , ” . : ” , ‘ , . — — , — — . , : , . , , ; ; ‘ . , . ‘ ; . , , , . , , . ‘ ; , , . , , , ; . . . ‘ , . ‘ . , , . , , ; , . , ; , . . , . , , . ; , — — , — — , , . ‘ , ‘ , ‘ . , ‘ . ‘ . ‘ , ‘ ; ; , . ; ? — — , , ‘ , ‘ , ‘ , . ; . , , , ‘ . . ‘ , ‘ , ‘ . ‘ , , ‘ , , ; , , . , . . . ” ” – ! ” . . ” , ” . . ” , ‘ . , ; , , ( ) . , ; . , . , , , ” , . . : ” ‘ ? ” ” , ‘ ? ” . . ” ; . ” ” — — ? ” . . ” , ; , ” . ” ; . , ‘ . ; , ; ( ) . , : , . ” ” , , ” . ” , ” . . ” . , , , . ; ; ‘ . ; . ‘ ; , ‘ . ” ; ” , ” . , ” ‘ . ” ” , , ” . ” , ” , ” ‘ . . ” ” , ” . , ” ‘ . . ” ” , ” . . ” ? ” ” . ; , – . , . ; , ‘ . ‘ , . , ; ; ‘ . ‘ ; . ” . . ” ? ” . ” . . . ” , . ” , , ” ; ” . , , . , , . . ” ” , ” . ” , . ; ‘ , . . ” . ; . ” , ” . ” . . ” ” , ” . ” , . ” . . . , , , , , . , , . , . ‘ . , . , ; , , . . , . . . , . . . , . . . , . , ” , ” . ‘ ” , ” ‘ ‘ . ‘ . , . . ; , , . . ; , , , . ” , ” , , ” . ” , , , , , . , . ” , , ” . ; , – . . , , , – , , . . , . , , ; . , , , , ‘ . , . ” , , ” , ” ? ” ” , ” . . ” . ? . ” ” ? ” . ” . ” ” , ” . ” . , ; ‘ , , . , ” , , ” . ” . . ” , ” ; ( ) , : ” ! ” , . ” — — ? ” . ” ? ” . ” . . . ” , , . , . ‘ . ‘ , . ; , ; , . ‘ . ; ; ‘ ; , . , , ; , , , ! , , . ; , , , , , . ; , , ; ‘ , , . . , , . ‘ ( ) . : : , , . , . – . , , , , . ” . , ” , ” . . ” . ; ; ; , , . ‘ , , – , , . ; ; . . , . , , , . ; , . , . , , . , , ‘ . , ; , . . . ” . , ? ” . . ; , : ” . ? ” ” , ” . ” . ‘ — — . — — ; , . ” ” . ; , ” . , . , , ” ? ” . ” , ” . ” ? ” ” , ” . ” ? ” ” ? ” . . , , , ; . ” , ” . . ” . ” ” , ” . , ” ; , . ” . ” ! ” . , ” , , ? ” . ” , ” , ” ? ” ” , ” . ” ? ” ” , ” . . ” , ” . , . ” ? ” ” , , ” . ” , ” . , . ” . ” ” , ” . , ” . ” ; , , . . , . , . , . . , , , , , ; , , . . ” , ” . ” , . , ! , ? . ? , , ? , ; , , ‘ , . ” – , , , ; – , , . , , , ; , , , . . – , . ” . , ? ” . ” , . , ” , , , , – , , ( ) , , . ” , ? – ? ” ” , , ” , . , , ‘ ; . ; ; ( ) ; , . , . . ” . , , ” . ” , . ? ” ” , . , , ” . ” . . ” ” , , ” . ” , , , ” . ” . ” ” . ? ” . ” , , . , ” . ” ; . ” ” , – , . ” ” – , . . ” . ” , ” , ” ! ; ; , . , ; , : , , – . ” , , , , – – – . ; ; , . , . ” , , ” , ” ; , ; ‘ . . ‘ ; , ! ; , . , — — , ” , ” . ” ‘ , , . . , , , , ; . . , . , . , – – ; , , ‘ . , . ; — — , – , – , , — — . . ” , , ” . ” ? ” ; . ” , ” , ” . ; – , , . , ‘ — — ‘ — — , ; – ; , . . ” ” , ” , . ” ? , , , ” , . ” . ” ” , , ” . ” . ” . , . ” , ” . ” . ” ” , ” . ” . , ” , . ” , ; — — . . ” ” , ” , ” : . ; . ” ” , ” , ” , , . ; , , , ; ‘ ; ; , : , . . ; ; , , ‘ ‘ : , . ” , . ” , ” , . ” , , , ” , ” . . ; ; . , ; , , . , ; . ” ” ‘ , ” . ” ‘ , ” , ‘ ; ” ; , . ” . ” , ” , ” . ” , , — — , . . , . , , , ‘ , . , , , . ( , , ) , . , ; , , . ( ‘ ) . ; , , ; , , – , , – – . , . , . , ; , – . , , , ( ) . , ; . . , – , , . , . ‘ . ; , . , , ; — — , , . : , , , . . , ; , . ” , ” ; ” . . ” , . , . ” , ” , ” . . ” ” , , ” , ” ? ” . ” , ” . ” . ” , . . ; , ; , . ” . ? ” . ” – , , ” . . ; , , ” , ” , ” . ” , . – , ; , . ; – ; , , ; , , , . , , , , , , ‘ , . , , ; , ‘ , . , , , , , , , , ; , , . ‘ ; . – – . , : . , , . ‘ , ; , ; ; , ; , . ” , , , ” ; , ” , ” . ” . ” ‘ . ” ! ” , ” ! ? ” . . ” ‘ , ” . ” , , . ” , , . ; . ; , ; , ( ) , ; . , , ; , ; – ; , . , ; ; , . , ‘ , . ” , , ” . : ” . , , , . , ‘ . , . ” , , ; . — — ; ; ; , . ; . , . . ‘ , , , . ; , . ‘ ; , , , , , , . , ; , . ‘ . , , , – , . ; , ; , , . , . , . ” , ” . , , ” ? ” . ” , ” . ” – . ” ” , ” . ” , , . ? ” ” , , ” , ” . . . ; ; , ; , . ” ; ‘ . ” , ” ; ” , . , . ” ” , ” ; ” . . — — ; . , ; , ; . ” ” , , ? ” . ” , ” . ” ; . , . ” ; ‘ , . ” , ” , , ” . ” , ” ” : , , ‘ , . , , , . ; ; . ” ? ” . ” , ” , ” . . . ” ” ? ” . ” , ” . ” . ” ” , , ” . ” : ? ” ; . ” , ” . ” . . ” ” , ” : ” — — , , ! ” . , . ” , ” , ” – : ? ” ; ” , ” . . ; , , ; , , . , , : ” . . . ” ; . , , ; – , . ; , , . , , . , , , , , . , ; , ‘ . . ; , ; , . . . ; . ‘ ; ; . ‘ ; : , , ? , , ? , , ; ; . . ” , ” . ” , , . , ” . ” , , . ” ” , ” . ” ; , ; . ; : ‘ . ” ‘ , . ” , ” : ” ; . ” ” , ” . . ” . , ? ” . ” . , . ? ” ” . ? ? ” ” . , ; ” . ” , , ” , ; ” ‘ . ” , . . ” , ? ” . ” , , ” , ” ‘ ; : . ” ” , ” . ” , , , ” . ” ‘ , , ” . ” , , ” . ” . ” . , , . ” ! ” . ” ! ” . . ; , ; . . , , : ‘ , ; , , ; , . , ; , , . , . , , . . , . . , , ; , . , , ; , ; , . ‘ ; ; . , , . ” , ” , ” . ” , , ; , . ; . ‘ . ; , ‘ . – . ; ; ; ‘ , – . ; . ” , ” ; ” , ; . ” , . ” , ” , ” . . , ; ; , , . , . ” ” , , ” . ” ? ” ‘ , . ” . , ” , . ” ; . ” ” , ! ” . ; , ” ‘ ? ” . ” , ; . ” ” , ” ; ” . ” ” , ” . ” , ” . ” , , , . . , , ‘ , ; , ‘ , , . ” , , , ; , , . . ” , ” , ” . ; , , . . . , . ; , , , . ” ; , ; , ; , , , . ; ‘ , . . , . , , , , . ” : . . , , ” ; . ” – , ” : ” ? ” , . , , ” . . ” . , ; , , . , ; . , ? , ; ; . , ; , , . ; . ; ; , , , , . , , . , , , ; , , ; . , . , . . , – ; , . ” , ” , ” ‘ . . . ” ” , ” . ” , ? ” ” , ” . ” , , . ‘ ! , . ” ” , ? ” . ” , . , ; , . ” , , , , . – ; , , , . . ” ! ! ” . ” . ” ” , , ” , ” . , . ” ” , ” . ” , . . ( — — . — — . . ) ; . ” ” , ” . ” ; , , , ; . , , ; ; . , . ” ” , , ” , – , ” . ” ” , ” . , , . ; , . , , – ; , , . . ; . ” , , ” . . . , . . , . ” , , ? ” ; , ” ? ” ; ” ? ” ” . , ” , ” . ” ” , , ” . ” , , . ” ” ‘ , , ” , ” . , ‘ ; ‘ , — — . . , , ‘ . ” ” , , ” , ” . ? ” ” ‘ , ” , , ” . ” ‘ ; ; , . , , . ” , ” . ” , ” , ” , ; . . ” ” ‘ , ” , . ” ! ” , . ” ! ? ” ” ‘ , , ” ; ” ? ” . ‘ ; ‘ , , . , , , , , . , . , ; . . ; – ; , . , , , . , , , , – . , , ; , , . ” , , ” , ” , . ” ” , , ” . ; ; , ” , ? ” ” ‘ , ” . ” . ” , , ; ; , , . . , ; , ” ! ‘ . , ” . ” , ? ? ” . ” , ; . ” ” ‘ , ” . , ; . ” ! ” , ; , , . ” , ” , – , ” , ‘ . ” . , . ” , , ” , ” . , ‘ . , , , ‘ . ” . ‘ , – , ; , , . ; , , . ” . , , , ” ; , . : ” , ” . ” , , ” , ; , . , . ” , ” , . , ” ‘ ? ” ” , ” , , . ” ? , , , ” . ” ‘ , ? , ; ‘ ; , ; ‘ , , , . ! ” ” , ; , ” . , . ” , . — — , , ? ‘ ; ‘ . ” ” , . , , ‘ , ” . ” ( ) , , , . — — ‘ , — — . ‘ ; , , . , , , , , , . , , , . , , . ” ” ? ” . . , , , . : ” . . . . — — , . . . . , , . . . . . ” , , ‘ . ” ‘ , ” , ” . ” ” , ” . ; , ” ? ” ” ‘ , , , ” . ” ‘ , ? ” . ” , ” ; , , ” ? ” . ” ‘ ! ” ” ? ” . . ” ? ” ” ‘ ! ” . ” . . ; , . , , . , . , , ? , , ? . . . . ” . ” , ” . , ” . , , ; , , ; ; , — — ! ; , , , ; , , . ” ” , ” , , ” , ‘ . ” — — — — ” , , . ” . ” , , ” , ” ? , ? , , . — — , . ; . ” ” , ” , ” , . ‘ , , . ” ” , . , ‘ ! ” . ” , ” : ” ? ” ” , , , ” . ” ‘ , ” ; ” , . ” ” , ” ; ” . ” , . ” , , ” , , ” ? ” ” , , , ” . ” , , ” . ” ; . , ? ” ” , , , , , ” . ” , . ? — — , , ! , ; , ; ? , , ? ‘ . ‘ , . , . ? ” ” , ” , ” . ” ” — — — — ‘ , , : . ” ” , ” . . ” , , ” . ” , , . , ‘ , . ; ‘ – ; , – . ! ” ” , , ” . ” . , , — — — — . , ; ; ( , ) ‘ . , . . ” , . ” , , ” . ” , , ; . , , . , . , , , . . ” , . ” , , , ” ; , . , . , , , , . ; , . ” , , ” ; ” , . , ‘ . , ‘ ‘ ! , , ‘ ! , — — , . , , ‘ ? ” , , ; . . ” ? ” . . ” , ” . ” ! ” ” ? ? ” , . ” , ” . ” , . ” . ; ; , , . ” , ” , , ” . ” , . ” , , , ” ; ” , — — , ! ” ” , ” , ” ‘ , ! ” ” , ‘ ‘ — — ‘ ‘ ! ” . ” , ! ” ; , . , , . , ; ; ; , . , , . , , , , , , ; , , , , . . , . , ‘ ; , ; , – . ” , ” , ” . ; . ” , , , . – ; . . . , , , , . , , , ‘ ; , . , . . ” , ” , . ” , ” , – . ; , , . ” , ” . ” ! ” . ” , , ? . ” ” , ” , ” , , . ” . ” , , ” . ” . ” , , . , , , . ” , ” ; , . , – , ‘ , . ; , , , , . , , – , . , , . ” , , ” . ” , ” . ” ” — — , — — ” ? ” . ” ! ” . . , , , , ‘ , . . , . , , ; , , . , , . ” , ” . ” ; ; ; . ” ; ‘ . ” ! ” , ” . ; , ! , ? ? , ? , . . ” ” ‘ , ? ” . ” , ” . ” ! ” : ” , — — , , , . , ; , ” , ” . ” ” ? ” . ” , , ” , . . ” . , . ; ; , . ” , ; , , . . ‘ , , , , . ; ; , , , ; . ; : ” , — — . ” , — — ; , , , . , , ‘ , , , , , ‘ . , , , , ; – , . , , . . ” – — — , ; , ; , . , , ; . ; ; ( ) , ; , , ( ) . , ; , : , . . ” : . , , ; , , . , , , , . . , , ; , , . ” , . , , , , , . , ” , ” . . ” . . — — . – , – . , , ; . ; , . ” , ; , . , ; . , , ‘ . ; , . ; . ‘ , ( ) ‘ . , ; , ; . , ‘ , . ; , , . . , ; ‘ ; . , , – , . . . , . , : ” ” ; , ” ! ! ! ” , , . , ( ‘ ) . , , ? , ? , ? ; , , – . ‘ , . , . ” . ? ” . ” ” ; , . , ‘ ; , . , , ; , . , , . , . , ; , , — — — — , . , . , , , ; , . ( , , ) ; , , , — — , , . , . , — — , — — ; ‘ , , , . , , . , , . ” ? ” . ” ? ” . , . ” , , ” . ” . , . ” , , , , , . ” , . , ” . ” ; . , . , ; . . . ” , , , — — ” , . . . ” ‘ , . ” , , ” , , . , , ; ; . ” , ” . , , . , . , , ” ? ” . . , . , , , , , , . , , . , , , , . ” , ” , ” . ? ? ? ? , . , , , . , , , , , ; . ” ” , ” , , ” , . . ” ” , ” . ” , : . , , , — — ! ” . ; , , , , ; , , — — — — — — , , , . ” ! ” , ” ! ” ; — — , , , — — ! , . , , ; , , . ; ; ; , ; . , , , , . , , ( ) . , ‘ , . . ‘ — — , , , , , , . , , , . ; , , . ; , . , , , , ‘ . , , . – , ; ; , , , . , , . , , , , : , . , . , ; , . , , , . , , ; , , , ; , , , , . , , , ; , ; , , . — — , . , ? , , . , , , . , . , . , ‘ , , . , , , ! , . , , , , , . . ; , , , . . ; , , , , ; , , , , , . : , , . , . , , , . , , ; , , , . , , , , ; , , . , ; , . , , ; , . , — — , , — — ; , , . , , , , ; , ; , . , , . , , . , , , , , , . , , , . , . ( ) . , , . , , . . , , . . , . , , , , : , , . : ; ; , , , , . – . , , , , . ; ; ; , . ; , , ; . , , , , . . , . ; ( ) , , , . . , , , , . ; ; . , ; . , . ( ) ; , , . ; . , . , , , . , . . , , , . , , . — — ! , ; , ; , , , , . , , ; . , . , . , , ; ; ; . ; , . , , , . ; ; , , . . ( ) ; . , , . – , ; ‘ ; ; , , , . , ; , , , . , , , . ; ; ; , , . , , , , , . , , . ( ) ; , , . , , – , , , , , . . , , ; . , . , , . ? ; , — — ? ; ; — — , , , – . ; , ? , . , , : , . ; , . , , . . , , , , ; . , ; , ( ) ; , , , , . . , , ; , , , ; . , , ‘ , , , , . ; , . , . , . ( ) , , ; , . ‘ ; ‘ . , . , , , , . ; ; , . , ; ; , , . , , ; , , , , . , , , . , , ; , , . ; ; , ; , , . , , , ; , , , . . , . , , , . , , ; , , , ; . ; , , , . . , , ; , , , . ; ; , , , . , ( ) ; , , , – , . , , . , , , . – . : , ‘ , – , , , . ; ; , , . , . . ; , ; , ! ! , ! , , , . , . ; . ; , . ; . , , ; , , . ; ; ; , , , , . ; : , ; . ; ; . ; , . , , , , ; ‘ . ; ; , , . , , ; , , – . , , . , ; , , , , . ; ; . . ‘ , , — — – ; , , , , . , . , ; , , . ; ? ( ) . . , . , . ? ? , ? , , , . ? , : ; , . , , , , . ( , ) . ; — — — — , . , , ; ; , , . ; , , . ; ; , ; , . , , ; , , ; , , , . , — — , . ; . , , , , , , . , , , , . , , , . , . ‘ , : ; . . , . ‘ ; . , . , , . , ; , ; . , , ; , . ; ! , , , – . , , , . , ; , , , . , , , , , , , : . , , ( ) , , . . . , . , – : , , , , . ; ; ; , , . , , ; , ; , , , . . , ; , , . – , , ; , , . ; : , , , , . , , ; , ; , — — , — — , ; , , . , , . ; , , ; . ; ; , . , . , , , , ( ! ) . ; , . , ; , – . . , , , , , ( ) . ? ? ; ; , . , , .

Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde—but just the punctuation.

Martian Time-Slip, Philip K. Dick. Ballantine Books, second printing (1976). Cover art by Darrell K. Sweet. 220 pages.

Martian Time-Slip, Philip K. Dick. Ballantine Books, second printing (1976). Cover art by Darrell K. Sweet. 220 pages.

I riffed on the novel a decade ago, writing,

Time-Slip rockets into rhetorical reverberation, cycling its final chapters into a strange decay. The timeslips jar the reader’s narrative perception—Hey wait, didn’t I already read this?—unsettling expectations, and ultimately suggesting that this Martian Time-Slip is just one version of Martian Time-Slip. That there are other timelines, distorted, slipped.

Hurricane Milton passed far enough south last night to leave our city relatively untroubled. There were power outages here but not the expected flooding. Most of my anxiety was focused on my family in the Tampa Bay area, all of whom are safe; we’re just not sure about the material conditions of the things they left behind.

Milton seemed to suck the summer air out of Northeast Florida; when I got out of bed and went outside to investigate the loud THUNK that woke me up at four a.m., I was shocked at how cold the air felt. It was only about 66°, but all the humidity seemed gone, even in the cold sprinkling rain. (The THUNK was our portable basketball hoop toppling over.)

I thought I might try to knock out a review or a write-up of one of the many books I’ve finished that have stacked up as the summer has slowly transitioned to autumn. College classes have been canceled through to Tuesday. I have, ostensibly a “free” week; maybe some words, harder to cobble together for me these days, would come together, no? For the past few years I’ve focused more on reading literature with the attempt to suspend analysis in favor of, like, simply enjoying it. I realized I’d gotten into the habit of reading everything through the lens of this blog: What was I going to say about the book after reading it? I’ve been happier and read more sense freeing myself from the notion that I need to write about every fucking book I read. But the good books stack up (quite literally in a little place I have for such books); I find myself simply wanting to recommend, at some level, however facile, some of the stuff I’ve read. So forgive this lazy post, organized around a picture of a stack of books. From the top down:

Forty Stories, Donald Barthelme

A few years ago, I read Donald Barthelme’s collection Sixty Stories in reverse order. A few days ago, a commenter left me a short message on the final installment of that series of blogs: “Now do Forty Stories.” I think I have agreed–over the past week I’ve read stories forty through thirty-five in the collection. More to come.

Waiting for the Fear, Oğuz Atay; translation by Ralph Hubbell

A book of cramped, anxious stories. Atay, via Hubbell’s sticky translation, creates little worlds that seem a few reverberations off from reality. These are the kind of stories that one enjoys being allowed to leave, even if the protagonists are doomed to remain in the text (this is a compliment). Standouts include “Man in a White Overcoat,” “The Forgotten,” and “Letter to My Father.”

Graffiti on Low or No Dollars, Elberto Muller

Subtitled An Alternative Guide to Aesthetics and Grifting throughout the United States and Canada, Elberto Muller unfolds as a series of not-that-loosely connected vignettes, sketches, and fully-developed stories, each titled after the state or promise of their setting. The main character seems a loose approximation of Muller himself, a bohemian hobo hopping freights, scoring drugs, and working odd jobs—but mostly interacting with people. It kinda recalls Fuckhead at the end of Denis Johnson’s Jesus’ Son (a book Graffiti spiritually resembles) praising “All these weirdos, and me getting a little better every day right in the midst of them.” Muller’s storytelling chops are excellent—he’s economical, dry, sometimes sour, and most of all a gifted imagist.

American Abductions, Mauro Javier Cárdenas

If I were to tell you that Mauro Javier Cárdenas’s third novel is about Latin American families being separated by racist, government-mandated (and wholly fascist, really) mass deportations, you might think American Abductions is a dour, solemn read. And yes, Cárdenas conjures a horrifying dystopian surveillance in this novel, and yes, things are grim, but his labyrinthine layering of consciousnesses adds up to something more than just the novel’s horrific premise on its own. Like Bernhard, Krasznahorkao, and Sebald, Cárdenas uses the long sentence to great effect. Each chapter of American Abductions is a wieldy comma splice that terminates only when his chapter concludes—only each chapter sails into the next, or layers on it, really. It’s fugue-like, dreamlike, sometimes nightmarish. It’s also very funny. But most of all, it’s a fascinating exercise in consciousness and language—an attempt, perhaps, to borrow a phrase from one of its many characters, to make a grand “statement of missingnessness.”

I liked Jon Lindsey’s debut Body High, a brief, even breezy drug novel that tries to do a bit too much too quickly, but is often very funny, gross, and abject. The narrator, who telegraphs his thoughts in short, clipped sentences (or fragments cobbled together) is a fuck-up whose main income derives from submitting to medical experiments. He dreams of scripting professional wrestling storylines though, perhaps one involving his almost-best friend/dealer/protector/enabler. When his underage-aunt shows up in his life, activating odd lusts, things get even more fucked up. Body High is at its best when it’s at its grimiest, and while it’s grimy, I wish it were grimier still.

Garbage, Stephen Dixon

I don’t know if Dixon’s Garbage is the best novel I’ve read so far this year, but it’s certainly the one that has most wrapped itself up in my brain pan, in my ear, throbbed a little behind my temple. The novel’s opening line sounds like an uninspired set up for a joke: “Two men come in and sit at the bar.” Everything that unfolds after is a brutal punchline, reminiscent of the Book of Job or pretty much any of Kafka’s major works. These two men come into Shaney’s bar—this is, or at least seems to be, NYC in the gritty seventies—and try to shake him down to switch up garbage collection services. A man of principle, Shaney rejects their “offer,” setting off an escalating nightmare, a world of shit, or, really, a world of garbage. I don’t think typing this description out does any justice to how engrossing and strange (and, strangely normal) Garbage is. Dixon’s control of Shaney’s voice is precise and so utterly real that the effect is frankly cinematic, even though there are no spectacular pyrotechnics going on; hell, at times Dixon’s Shaney gives us only the barest visual details to a scene, and yet the book still throbs with uncanny lifeforce. I could’ve kept reading and reading and reading this short novel; it’s final line serves as the real ecstatic punchline. Fantastic stuff.

Magnetic Field(s), Ron Loewinsohn

I ate up Loewinshohn’s Magnetic Field(s) over a weekend. It’s a hypnotic triptych, a fugue, really, with phrases sliding across and through sections. We meet first a burglar breaking into a family’s home and learn that “Killing the animals was the hard”; then a composer, working with a filmmaker; then finally a novelist. Magnetic Field(s) posits crime and art as overlapping intimacies, and extends these intimacies through imagining another life as a taboo, too-intimate trespass.

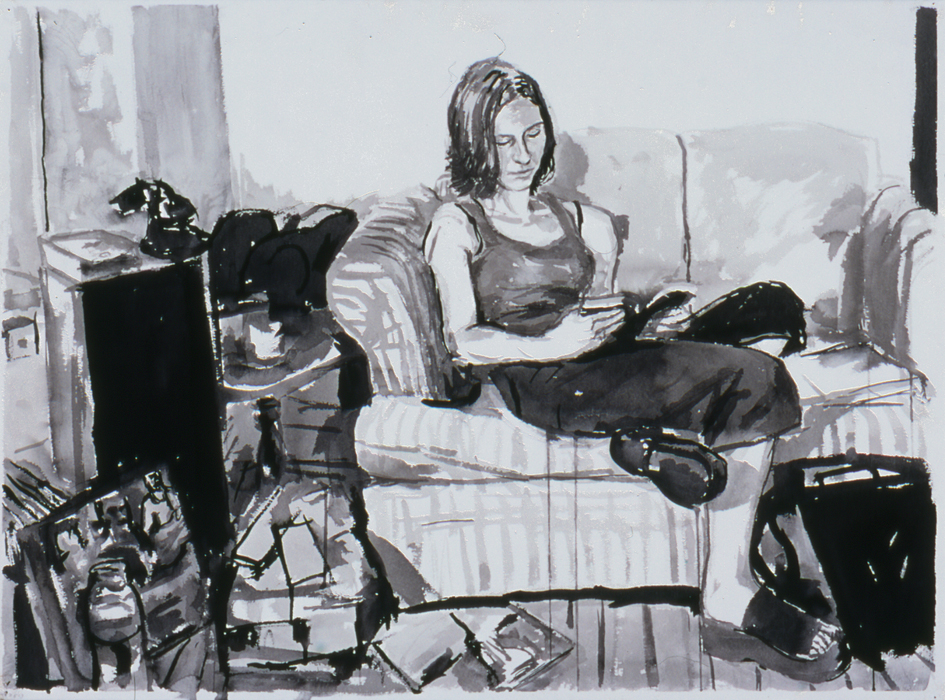

Making Pictures Is How I Talk to the World, Dmitry Samarov

Making Pictures spans four decades of Samarov’s artistic career. Printed on high-quality color pages, the collection is thematically organized, showcasing Samarov’s different styles and genres. There are sketches, ink drawings, oils, charcoals, gouache, mixed media and more—but what most comes through is an intense narrativity. Samarov’s art is similar to his writing; there isn’t adornment so much as perspective. We get in Making Pictures a world of bars and coffee shops, cheap eateries and indie clubs. Samarov depicts his city Chicago with a thickness of life that is better seen than written about. Some of my favorite works include interiors of kitchens, portraits of women reading, and scribbly but energetic sketches of indie bands playing live. What I most appreciate about this collection though is that it showcases how outside of the so-called “art world” Samarov’s work is–and yet this is hardly the work of a so-called “outsider” artist. Samarov trained at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and yet through his career he has remained an independent, “not associated with an institution such as an art gallery, college, or museum,” as he writes in his book.

Final Cut, Charles Burns

I don’t know anything about Charles Burns’s upbringing, his youth, his personal life, and I don’t mean to speculate. However, it’s impossible not to approach Final Cut without pointing out that for several decades he’s been telling the same story over and over again—a sensitive, odd, artistic boy who is out of place even among others out of place. This is in no way a complaint—he tells the story with difference each time. And with more coherence. Final Cut is beautiful and sad and also weird enough to fit in neatly to Burns’s oeuvre. But it’s also more mature, a mature reflection on youth really, intense, still, but without the claustrophobia of Black Hole or the mania of his Last Look trilogy. There’s something melancholy here. It’s fitting that Burns employs the heartbreaking 1971 film The Last Picture Show as a significant motif in Final Cut.

RIP Robert Coover, 1932-2024

Robert Coover passed away a few days ago at ninety-two years old. In his decades-spanning career, Coover published twenty-one novels, four plays, and four short story collections. He also published dozens of (as-yet) uncollected stories, essays, and a host of so-called “electronic fiction.” A fifth short story collection, 2018’s Going for a Beer, collected some of Coover’s greatest hits, and is generally an excellent starting place for those interested in Coover’s metatextual fabulism.

Coover didn’t start out as a metatextual fabulist. His first novel, 1966’s The Origin of the Brunists, is vivid, humanist realism with the slightest tinges of magic brightening its edges. 1968’s follow-up, The Universal Baseball Association, Inc., J. Henry Waugh, Prop., strays much deeper into the pop-myth fantasies that Coover would perfect in his mature career.

Coover’s 1969 collection Pricksongs & Descants shows a remarkable shift into postmodern metafiction. Pricksongs features some of his better stories, like “The Brother” (told from the point of view of the biblical Noah’s brother), “The Elevator,” and “The Magic Poker,” which begins with the sentence “I wander the island, inventing it” — a tidy encapsulation of Coover’s growing motif of the self-creating story. At times, this metatextual motif can exhaust the reader, as in Pricksongs’ capper “The Hat Act.” However, the collection features one of Coover’s best stories, “The Babysitter,” in which the titular character serves as a locus for a mundane suburban community’s collective repressed anxieties of sex and violence.

Coover would continue to explore such themes throughout his career, refining and sharpening his metatextual hat act in standout novels like Spanking the Maid (1982), Gerald’s Party (1986), and 1977’s The Public Burning—arguably Coover’s most important novel. It’s easy to think of The Public Burning as the last part of a loose postmodern American trilogy of large daring novels, the first two parts comprised of Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (1973) and William Gaddis’s J R (1975).

Indeed, Coover was regularly grouped with a (very white, very male) clique of postmodern American writers. In his 1980 essay “The Literature of Replenishment,” John Barth halfheartedly counted up the members: “By my count, the American fictionists most commonly included in the canon, besides the three of us at Tubingen [William H. Gass, John Hawkes and Barth himself], are Donald Barthelme, Robert Coover, Stanley Elkin, Thomas Pynchon, and Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.”

There was some chatter on social media that Coover’s passing left just Pynchon–and maybe Don DeLillo and Joseph McElroy–as the last living luminaries of twentieth-century US American postmodernist fiction. Of course, Pynchon really wasn’t a member of this or any other clique (he declined an invitation to Donald Barthelme’s so-called “postmodernists dinner“), and, as is too often the case with such groupings, Ishmael Reed’s contribution to American postmodernist fiction continues to be marginalized.

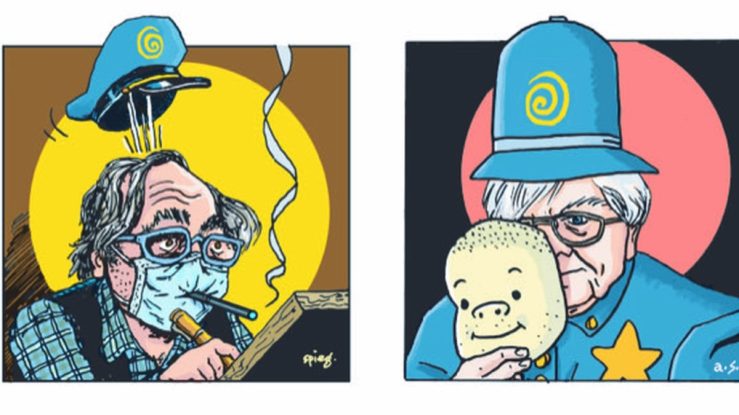

Let it stand then that Robert Coover, despite whatever connections and friendships he held with other writers and artists, was his own special self-made creation. He was prolific, especially later in life, publishing nine novels in the twenty-first century. One of these was The Brunist Day of Wrath (2014), a sequel to his debut; he also collaborated with comix artist Art Spiegelman on the graphic novelette Street Cop (2021) and even found a sliver of mainstream readers with Huck Out West, his wonderful 2017 “sequel” to Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Coover’s latest novel Open House was published just over a year ago.

Clearly, Coover leaves behind a large body of work, and we’ll likely see more of his work collected and published over the next decade. I won’t pretend to have read most of what he’s written, but I’ve loved a lot of it—particularly Pricksongs & Descants, Huck Out West, Spanking the Maid, and Briar Rose, which, as far as I can recall, is likely the first thing I read of his (my girlfriend at the time’s sister had to read it in college; she professed that she hated it but thought I’d like it). The aforementioned 2018 collection Going for a Beer is a nice starting place for Coover; those more interested in novels might like Spanking the Maid. Or jump into one of his later short novels, like 2004’s Stepmother or 2018’s The Enchanted Prince, both of which exemplify his metamagicianist mode. Or hell, just go for the big boy, The Public Burning. Ultimately, Coover leaves behind a trove of trembling, writhing, vividly-living words, an oeuvre that will continue to engage readers fascinated by a certain stamp of so-called experimental literature–and for that I thank him.

The Origin of the Brunists, Robert Coover. Banatm Books Edition (1978). No cover designer credited. 534 pages.

This Bantam reprint of Coover’s first novel coincided with their mass-market paperback publication of The Public Burning.

I wrote a bit on The Origin of the Brunists a few years back. From that riff:

Coover’s metafiction always points back at its own origin, its own creation, a move that can at times take on a winking tone, a nudging elbow to the reader’s metaphorical ribs—Hey bub, see what I’m doing here? Coover’s metafictional techniques often lead him and his reader into cartoon landscapes, where postmodernly-plastic characters bounce manically off realistic contours. The best of Coover’s metafictions (like “The Babysitter,” 1969) tease their postmodern plastic into a synthesis of character, plot, and theme. However, in large doses Coover’s metafictions can tax the reader’s patience and will—the simplest example that comes to mind is “The Hat Act” (from Pricksongs & Descants, 1969), a seemingly-interminable Möbius loop that riffs on performance, trickery, and imagination. (And horniness).

I’m dwelling on Coover’s metafictional myth-making because I think of it as his calling card. And yet Origin of the Brunists bears only the faintest traces of Coover’s trademark metafictionalist moves (mostly, so far anyway, by way of its erstwhile hero, the journalist Tiger Miller). Coover’s debut reads rather as a work of highly-detailed, highly-descriptive realism, a realism that pushes its satirical edges up against the absurdity of modern American life. It reminds me very much of William Gass’s first novel Omensetter’s Luck (1966) and John Barth’s first two novels, The Floating Opera (1956) and The End of the Road (1958). (Barth heavily revised both of the novels in 1967). There’s a post-Faulknerian style here, something that can’t rightly be described as modern or postmodern. These novels distort reality without rupturing it in the way that the authors’ later works do. Later works like Barth’s Chimera (1973), Gass’s The Tunnel (1995), and Coover’s The Public Burning (1977) dismantle genre structures and tropes and rebuild them in new forms.

Heroes and Villains, Angela Carver. Pocket Books Edition (1972). No cover artist credited. 176 pages.

While no cover designer or artist for this edition of Angela Carter’s 1969 novel Heroes and Villains, I’m pretty certain that the work is by Gene Szafran.

I wrote briefly on the novel in 2020:

One of Carter’s earlier novels, Heroes and Villains takes place in a post-apocalyptic world where caste lines divide the Professors, the Barbarians, and the mutant Out People. After her Professor stronghold is raided, Marianne is…willingly abducted?…by the barbarian Jewel. Marianne goes to live with the Barbarians, and ends up in a weird toxic relationship with Jewel, marked by rape and violence. Heroes and Villains throws a lot in its pot—what is consent? what is civilization? what is language?—but it’s a muddled, psychedelic mess in the end.

We have the right to convey the fictive of any reality at all–and there is nothing that is not real—by any method we wish, and to have as our goal, if we so opt, only that we maintain the reader’s tension, the solitary indication, itself mercurial, of a work-of-art event.

Syntax being nothing more nor less than the codification of selected usages, we may alter syntax or reject it wholly.

We may compose the fictive in such a manner that the result is ambiguous, baffling and sometimes altogether impossible significantly to paraphrase-but so long as the piece seizes and holds the reader, a basic meaning, impossible to state in language as we know it, has been established, a meaning that belongs to a time series of seizing-and-holding.

The notion, we submit, of clarity, remains simply a notion, real enough, of course, under whatever category it is sub-sumed, but of no universal vigor, necessarily, nor marked by socalled objective truth; clarity is a notion identifying a particular social agreement in a one-to-one sense as to what construct evokes similarity of analysis.

Empirically all that is demonstrable is that we experience as creator or audience a series of perceptions. Now, if we set forth that demonstration in the fictive in such a fashion as to generate and sustain tension in the reader whether or not he is mystified by the significs, we have met the sole possible criterion.

We are not of course here in any way concerned with the alleged scalar values of a given fiction-the notion of value belongs to ad hominen pleaders usually involved in depressing or elevating a status for economic reasons—just as we cannot in any way be concerned with the alleged scalar values of the given reader. Fiction and reader are conjoined, and may not with any sense be disjunct if we are trying to penetrate the nature of the esthetic.

Such being the case, I believe we can with some innocence look at the choices of the contemporary avant-garde herein, and digest them according to our lights or chiaroscuras.

We need remember only how much more we usually discern if we take the trouble, to begin with, to clean our own canvasses-within reason.

—Gil Orlovitz

Gil Orlovitz’s introduction to The Award Avant-Garde Reader (1965).

The Public Burning, Robert Coover. Banatm Books Edition (1978). No cover designer credited. 661 pages.

A 1977 Book Ends column in The New York Times offers a fairly succinct blurb for The Public Burning:

The Public Burning is a blend of fact and fantasy, using dozens of real and fictional names. Among the real persons named in this “metafiction” are President Eisenhower, Senator Joseph McCarthy, J. Edgar Hoover, Billy Graham, Norman Vincent Peale, Edward Teller, Walt Disney, Cecil B. DeMille, former prosecuting attorney Irving Saypol and Judge Irving Kaufman. About one‐half of the novel narrated by Vice President Richard M. Nixon…

The Book Ends piece, which appeared a few months before the book’s publication (and notes the difficulties the book found securing a publisher brave enough to put it out), includes a brief interview with Coover about The Public Burning:

“I had the idea for the book 11 years ago. I thought it would be a novella and not a book of over 500 pages. I felt that the event was something that had been repressed. If you mentioned the Rosenberg case, people were turned off or young persons didn’t know what it had been all about.

“Their execution — plus the prevalence of old‐fashioned American hoopla—gave me the central metaphor for the book. In 1968, I was looking for a narrator. After Nixon was elected President, he served that purpose. He had been a participant in the background of the Rosenberg case. As President, he was powerful, pious and pompous. I needed a clown act to intersperse with the circus act. And so Nixon became the clown. Clowns are sympathetic when you get to know them.”

The Public Burning was the first book I read by Coover, and I read it when I was too young to fully appreciate it; I think I simply wasn’t soaked enough in its history. Revisiting it, even in brief today, reminded me that it’s likely as relevant as ever, and that its diagnoses of the first half of America’s twentieth century is up there with Gravity’s Rainbow or J. R.

Two years after it was first published in Italy, Dino Buzzati’s 1960 novella Il grande ritratto got its first English translation by Henry Reed under the title Larger Than Life. This year, NRYB issued a new translation of Il grande ritratto by Anne Milano Appel under the title The Singularity. This is the second new English translation of a Buzzati book from NYRB; last year saw the publication of Lawrence Venuti’s translation of Buzzati’s most famous novel, Il deserto dei Tartari, published as The Stronghold (in lieu of the more recognizable title The Tartar Steppe).

It makes sense, from both a cultural and a marketing stance, that Il grande ritratto would find new life as The Singularity, a term that refers to the hypothetical point where artificial intelligence surpasses human intelligence, which in turn triggers a dramatic existential change for humanity. AI slop abounds on the internet; misinformation replicates and mutates; we are told that the chatbots that frustrate us so frequently are an inevitable part of a future that no one seems to want. A sci-fi novel called The Singularity is pretty zeitgeisty.

The scant plot of The Singularity builds to the revelation of an artificial intelligence, part of a military science project perched high in the Italian Alps. I don’t think I’ve necessarily spoiled the grand reveal; both its title and its publisher’s blurb declare The Singularity “a startlingly prescient parable of artificial intelligence.”

Perhaps it’s this prescience that makes the central sci-fi conceit of The Singularity seem a bit dated. There’s a creakiness to Buzzati’s staging of his grand portrait of an artificial intelligence. The novella is more compelling in its initial chapters, which ignite a mood of slow-burning dread, the kind of Kafkaesque foreboding he served up in his superior novel Il deserto dei Tartari.

That slow-burn starts with a certain Professor Ismani, “who had always had an inferiority complex with respect to figures.” He and his much younger wife, the archetypal innocent Elisa (who “had not gone beyond middle school”) agree to undertake a mysterious journey up the mountain to “Experimental Camp of Military Zone 36,” where Ismani will join a scientific project he knows nothing about. As they zig and zag up the mountain, chauffeured by their military liaison, Ismani and Elisa (and the reader) gather crumbs about their destination. “So many mysteries,” a soldier tells them, at a penultimate stop. “If they at least told us what it is we’re guarding. I mean, let’s call it what it is, a kind of prison.”

In response to all this anxious foreboding, we are told that “Ismani felt the return of apprehension and dismay, the feeling of being insignificant in the face of immense, threatening things, a panic that he had once experienced in the war.” None of Ismani’s time in the war comes to bear on the narrative itself. Indeed, Ismani is thrown to the reader as a decoy; initially presented to the audience as the potential big-brain hero of a sci-fi thriller, he ends up a background ghost.

We eventually achieve the summit, where the natural splendor is overrun by the enormous complex that houses the titular singularity:

But the cliffs were no longer visible, nor could any vegetation be seen, or land, or flowing waters. Everything had been invaded and overwhelmed by a tangled succession of buildings similar to silos, towers, mastabas, retaining walls, slender bridges, barbicans, fortifications, blockhouses, and bastions, which plunged in dizzying geometries. As though a city had crashed down the sides of a ravine.

But there was an exceedingly abnormal element that gave those structures an air of enigma. There were no windows. Everything seemed hermetically sealed and blank.

From this moment, more or less, the best bits of The Singularity come not from sci-fi plotting but rather philosophical asides that add weight to the pulp narrative. Most of these are delivered by the handful of scientists who haunt the experimental camp. One of these scientists repeats the mantra, “Language is the worst enemy of mental clarity.” In their attempt to author an artificial consciousness, these scientists decreed that their singularity would have “No language,” for “Every language is a trap for the mind.”

Here in their “little kingdom, hermetically closed off and apart from the rest of the world,” the scientists have created a “machine made in our likeness” which “will read our thoughts, create masterpieces, reveal the most hidden mysteries.” Through hints, intimations, weird noises, and other creaky trappings of pulp horror, we come to learn that the singularity might not be, like, sane. As one of our (maybe not like exactly sane either) scientists declares, “before we knew it we had lost the reins, and all that was left for us to do was to record the machine’s behavior.”

In a move that would surprise no one familiar with the tropes of Gothic romance, we come to learn that the singularity’s consciousness is based on a beautiful dead woman. The whole operation is powered by a mysterious glowing egg. Indeed, The Singularity is perhaps most interesting if approached through a feminist lens. As it rushes to its climax, Elisa the innocent takes over the role of hero. She somehow learns to speak the strange “language” of the pre-lingual singularity, and through conversation, comes to understand that the singularity views herself as a desiring machine. The singularity wants a body; specifically a female body; specifically a body that can be desired by a male body and bear offspring.

Ultimately, The Singularity feels less like a novella than it does a short story stretched a bit too thin. Buzzati adroitly crafts an atmosphere of suspense and foreboding, but the characters are underdeveloped. Like a lot of pulp fiction, Buzzati’s book often reads as if it were written very quickly (and written expressly for money). Still, Buzzati’s intellect gives the book a philosophical heft, even if it sometimes comes through awkwardly in forced dialogue. Anne Milano Appel’s translation is smooth and nimble; it’s a page turner, for sure, and if it seems like I’ve been a bit rough on it in this paragraph in particular, I should be clear: I enjoyed The Singularity.

Like many of the modernist writers of the twentieth century, Buzzati intuited a future in which technology would become increasingly self-propelled, mutating unchecked in the notion of a progress wholly divorced from the needs of the human spirit. In our own era, we see con artists and hucksters banging the drum for “artificial intelligences” to “read our thoughts, create masterpieces, reveal the most hidden mysteries” for us. The results have been utter shit. Buzzati’s mad scientist isn’t so much prescient as he is simply describing the human condition then, when he declares that “man is doomed to torment himself, he doesn’t see the consolations offered to him, right there, within reach, he has to constantly fabricate new agonies for himself.” We can fabricate the agonies, but we can fight them too.

Star Maker, Olaf Stapledon. Penguin Books (1973). Cover design by David Pelham. 268 pages.

Here is the first paragraph of Star Maker:

ONE night when I had tasted bitterness I went out on to the hill. Dark heather checked my feet. Below marched the suburban lamps. Windows, their curtains drawn, were shut eyes, inwardly watching the lives of dreams. Beyond the sea’s level darkness a lighthouse pulsed. Overhead, obscurity. I distinguished our own house, our islet in the tumultuous and bitter currents of the world. There, for a decade and a half, we two, so different in quality, had grown in and in to one another, for mutual support and nourishment, in intricate symbiosis. There daily we planned our several undertakings, and recounted the day’s oddities and vexations. There letters piled up to be answered, socks to be darned. There the children were born, those sudden new lives. There, under that roof, our own two lives, recalcitrant sometimes to one another, were all the while thankfully one, one larger, more conscious life than either alone.

More David Pelham covers here.

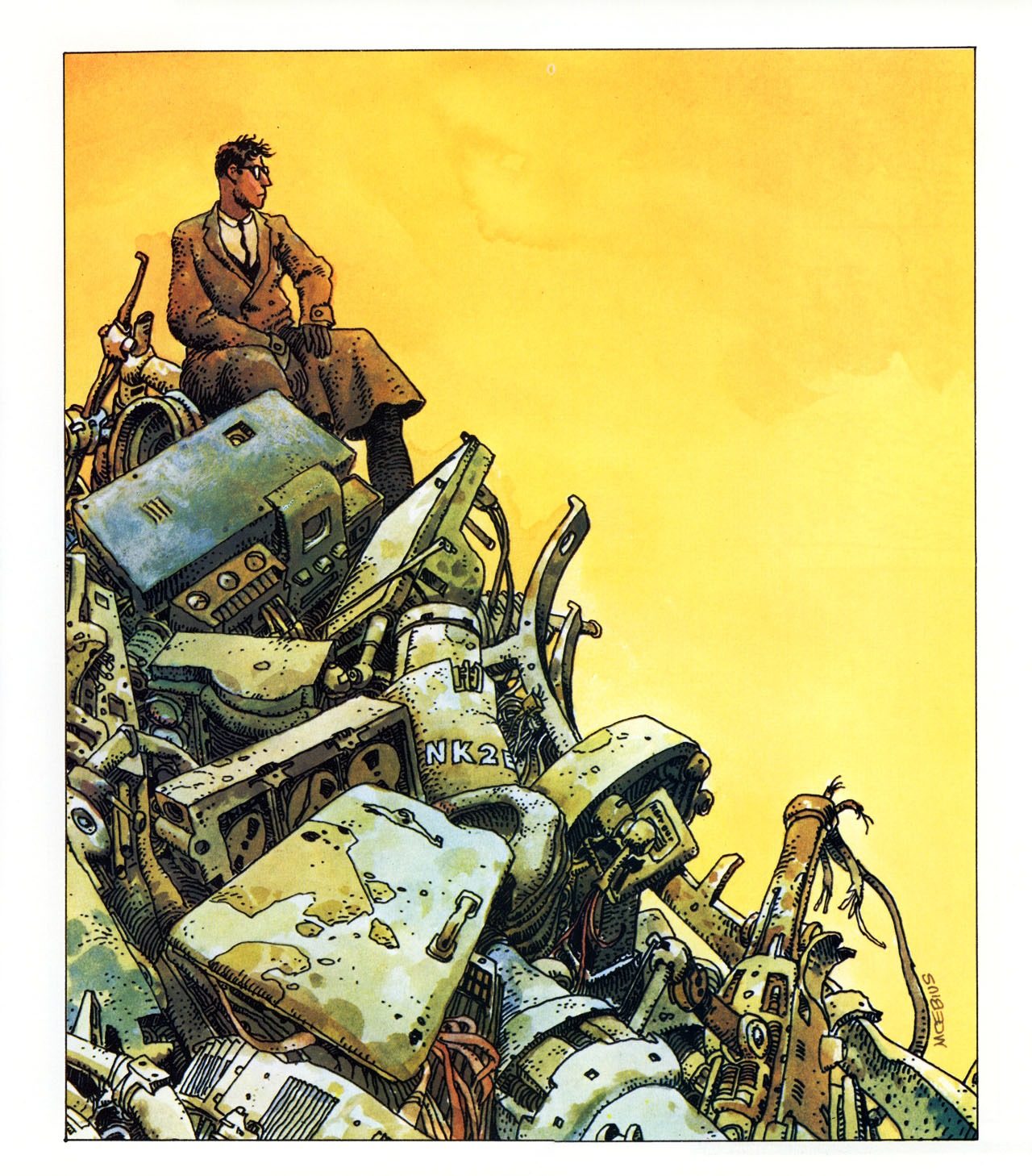

Cover illustration for the French translation of Kurt Vonnegut’s novel Player Piano, 1975 by Moebius (Jean Giraud, 1938–2012)

An illustrated manuscript page from Alasdair Gray’s novel Lanark. From the Glasgow University Library Special Collections Department.

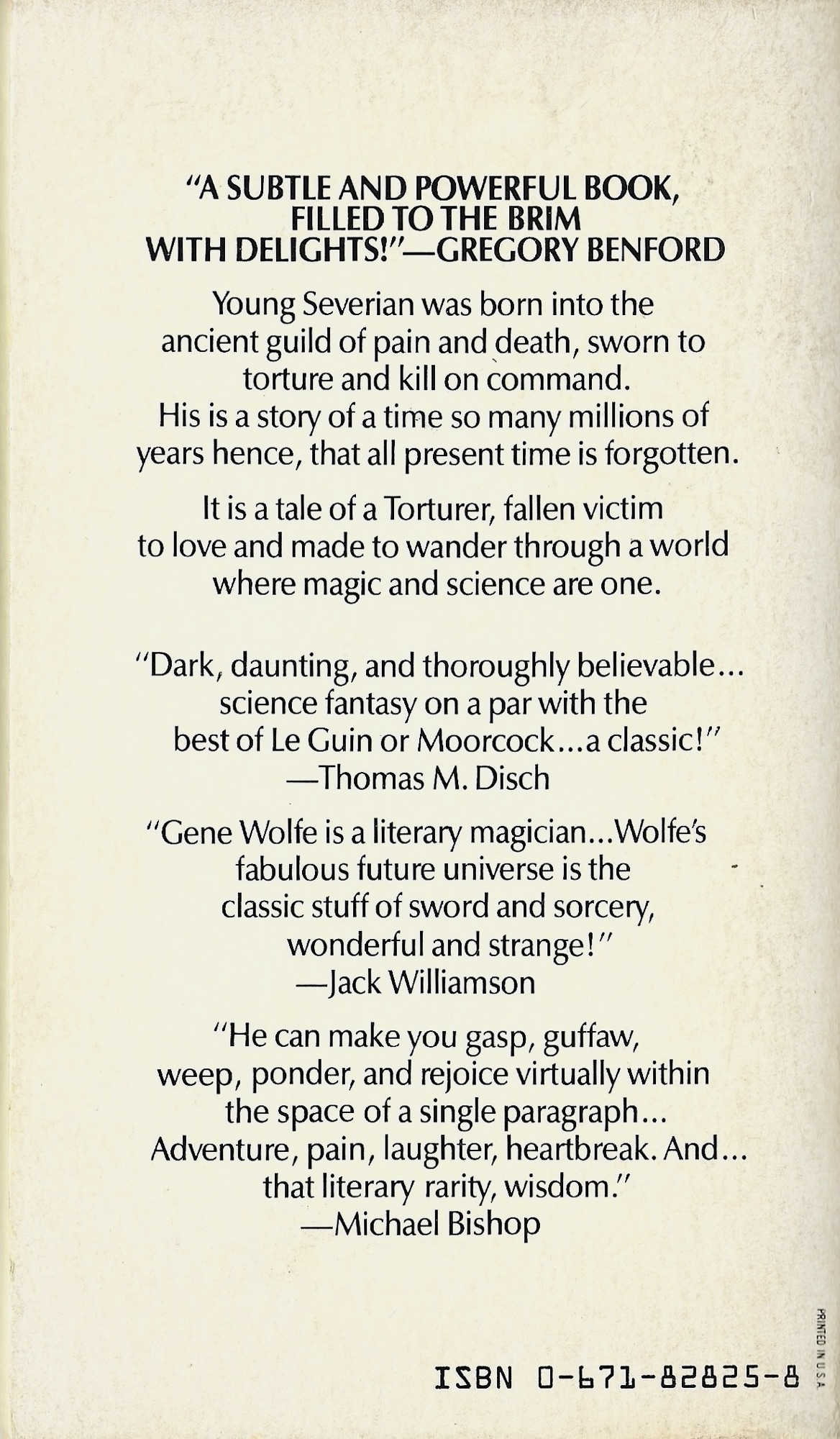

The Shadow of the Torturer, Gene Wolfe. Timescape/Pocket Books (1981). No cover designer or artist credited. 262 pages.

While no cover artist is credited, Don Maitz is the artist for this edition of The Shadow of the Torturer, as well as for the other three books in Wolfe’s Book of the New Sun tetralogy. Maitz is credited on the dust jackets of the original hardback first editions (Simon & Schuster) of the series.

The Book of the New Sun is absolutely astounding.

From Peter Bebergal’s 2015 New Yorker profile on Wolfe, “Sci-Fi’s Difficult Genius”:

For science-fiction readers, “The Book of the New Sun” is roughly what “Ulysses” is to fans of the modern novel: far more people own a copy than have read it all the way through. A surreal bildungsroman, the book centers on a character named Severian. Trained as a torturer on the planet Urth, where torturers are a feared and powerful guild, Severian betrays his order by showing mercy, allowing a prisoner to kill herself rather than be subjected to his terrible ministrations. He then wanders the land encountering giants, anarchists, and members of religious cults. He eventually meets and supplants the ruler of Urth, the Autarch.

The four books that make up the series are sometimes vexing. A wise reader will keep a dictionary nearby, but it won’t always prove useful. Though Wolfe relies merely on the strangeness of English—rather than creating a new language, like Elven or Klingon—he nonetheless dredges up some truly obscure words: cataphract, fuligin, metamynodon, cacogens. The setting appears medieval, but slowly we tease out that what is ancient to these characters was once our own possible future. A desert’s sands are the glass of a great city, and the creaking steel walls that make up Severian’s cell in the guild dormitory is likely an ancient spaceship. Reading “The Book of the New Sun” is dizzying; at times, you become convinced that you have cracked a riddle, and yet the answer fails to illuminate the rest of the story. Wolfe doesn’t reveal the truth behind any of the central mysteries explicitly, but lets them carry the narrative along. At first, one hopes that they will eventually be resolved. Ultimately, they become less important than Severian’s quest for his own truth.

Go Down, Moses, William Faulkner. Vintage Books Edition (1971). Cover photo by Robert Wenkham. 383 pages.

Go Down, Moses is my favorite William Faulkner text (some say it’s a collection of stories, but I think it’s a novel). “The Bear” might be the best thing he wrote. Read the opener, “Was.”

From “Was”:

Isaac McCaslin, ‘Uncle Ike’, past seventy and nearer eighty than he ever corroborated any more, a widower now and uncle to half a county and father to no one

this was not something participated in or even seen by himself, but by his elder cousin, McCaslin Edmonds, grandson of Isaac’s father’s sister and so descended by the distaff, yet notwithstanding the inheritor, and in his time the bequestor, of that which some had thought then and some still thought should have been Isaac’s, since his was the name in which the title to the land had first been granted from the Indian patent and which some of the descendants of his father’s slaves still bore in the land. But Isaac was not one of these:-a widower these twenty years, who in all his life had owned but one object more than he could wear and carry in his pockets and his hands at one time, and this was the narrow iron cot and the stained lean mattress which he used camping in the woods for deer and bear or for fishing or simply because he loved the woods; who owned no property and never desired te since the earth was no man’s but all men’s, as light and air and weather were; who lived still in the cheap frame bungalow in Jefferson which his wife’s father gave them on their marriage and which his wife had willed to him at her death and which he had pretended to accept, acquiesce to, to humor her, ease her going but which was not his, will or not, chancery dying wishes mortmain possession or whatever, himself merely holding it for his wife’s sister and her children who had lived in it with him since his wife’s death, holding himself welcome to live in one room of it as he had during his wife’s time or she during her time or the sister-in-law and her children during the rest of his and after not something he had participated in or even remembered except from the hearing, the listening, come to him through and from his cousin McCaslin born in 1850 and sixteen years his senior and hence, his own father being near seventy when Isaac, an only child, was born. rather his brother than cousin and rather his father than either, out of the old time, the old days.

When he and Uncle Buck ran back to the house from discovering that Tomey’s Turl had run again, they heard Uncle Buddy cursing and bellowing in the kitchen, then the fox and the dogs came out of the kitchen and crossed the hall into the dogs’ room and they heard them run through the dogs’ room into his and Uncle Buck’s room then they saw them cross the hall again into Uncle Buddy’s room and heard them run through Uncle Buddy’s room into the kitchen. Where Uncle Buddy was picking the breakfast up out of the ashes and wiping it off with his apron. “What in damn’s hell do you mean,” he said “turning that damn fox out with the dogs all loose in the house?”

“Damn the fox” Uncle Buck said. “Tomey’s Turl has broke out again. Give me and Cass some breakfast quick we might just barely catch him before he gets there.”

P’s Three Women, Paulo Emílio Sales Gomes. Translation by Margaret A. Neves. Avon Bard (1984). No cover artist credited. 136 pages.

Gomes’s only novel got a reprint from Dalkey Archive back in 2012 with a new introduction by translator Margaret Neves, who notes that in “Portuguese, the title of this book is Trés Mulheres de trés PPPés. The expression “p-p-p” means chitchat, bla-bla-bla. Hence, three women and their chitchats. In addition to echoing the narrator’s first initial, the term is lightly condescending to the women, just like P himself.”