Listen to Tom McCarthy on KCRW’s Bookworm program.

Listen to Tom McCarthy on KCRW’s Bookworm program.

Read our review of Tom McCarthy’s new novel C.

Listen to Tom McCarthy on KCRW’s Bookworm program.

Listen to Tom McCarthy on KCRW’s Bookworm program.

Read our review of Tom McCarthy’s new novel C.

Read our review of Tao Lin’s new novel Richard Yates.

Do you know about the Oedipal complex? That Freudian thing? Of course you do. But if for some reason you don’t, or need a refresher, here’s a quick summary from one of my all time favorite lyricists, David Byrne: “Mom and Pop / They will fuck you up / For sure.” That joyful nugget is from one of the last songs Talking Heads recorded, “Sax and Violins,” a great little piece on modern life that is far more entertaining (and much shorter) than Jonathan Franzen’s over-hyped new novel Freedom.

Freedom works hard to prove that Mom and Pop will fuck you up. Your family will fuck you up. Then you will fuck up your own kids. Franzen’s (boring, oh my god are they boring) characters seem bound to play out repeated variations of the Oedipal complex. Furthermore, according to Freedom, our extra-familial relationships are merely substitutions or recapitulations of our own Oedipal family dramas. Even worse, Franzen seems to suggest in Freedom that all our ideologies, our passions, our beliefs are really just formed by our “morbidly competitive” impulses, impulses born in our fucked-up, Oedipal families. (“Morbidly competitive,” by the way, is Franzen’s term).

The novel centers on one family, the Berglunds, a perfectly normal (in the upper-middle-class-white-educated sense of “perfectly normal”) fucked up family of four. I’m dispassionate about this novel, so I’ll just lazily crib a short summary from a well-written piece I’m largely simpatico with, Ruth Franklin’s review at TNR—

Freedom takes place over a period of about thirty years, but its primary focus is on the George W. Bush era. When it begins, Patty and Walter Berglund, college sweethearts, are among the first wave of urban pioneers putting the gentry back into gentrification, fixing up a house in a blighted area of St. Paul that they will soon populate with their two children. The short preamble offers an overview of their lives from the perspective of their neighbors, from the time they move in as a young couple to their departure around the time the children leave for college. Patty, a former college basketball star who once made “second-team all-American,” is a mother and housewife in the newly popular liberal model: “tall, ponytailed, absurdly young, pushing a stroller past stripped cars and broken beer bottles and barfed-upon old snow. . . . Ahead of her, an afternoon of public radio, the Silver Palate Cookbook, cloth diapers, drywall compound, and latex paint; and then Goodnight Moon, then zinfandel.” She bakes cookies for the neighbors on their birthdays and opens her house to their children. But Patty’s baking and mothering cannot keep her home together: her son Joey, while still in high school, moves out to live down the street with his girlfriend Connie and her family, which happens to include the only Republican on the block. The strain that their child’s defection places on the Berglunds’ marriage is obvious to all. When they leave in the early 2000s for Washington, where Walter has a new job doing something vaguely ominous involving the coal industry, one of the neighbors remarks, “I don’t think they’ve figured out yet how to live.”

This overture sets the stage for the rest of the book, which begins and more or less ends with a ridiculously well-written journal by Patty. Patty (who is somehow a more-than-competent novelist despite having no training) allows the audience to witness her marriage crumbling from her perspective; we are also supposed to sympathize with her because her own childhood was fucked up by her family. Also, she was date-raped, a manipulative detail that adds little to the narrative (I’d call it Nice Writing at its worst). Patty’s seemingly interminable journal eventually gives way to shorter chapters focusing on Joey and Walter. There’s also Patty and Walter’s lifelong friend, ex-punk/would-be indie rock star Richard Katz. Much of the novel revolves around Patty’s desire for Richard and Walter’s desire for Richard (no homo) and Richard’s desire for what he thinks Walter and Patty have and Walter’s desire to be desired by Patty the way that Patty desires Richard and blah blah blah. It’s one big boring circle of “morbidly competitive” Oedipal tension. Franzen spends most of his time expounding on how each character feels about how another character feels about him or her in an endless solipsistic chain that fails to enlighten or even amuse. Too much telling, not enough showing.

Freedom threatens to become interesting when it picks up the Walter narrative. Walter, a die-hard environmentalist oozing oodles of liberal guilt, is hard at work with a bevy of über-Republicans and defense contractors and Texas oil men to save the planet. Via the novel’s ever-present free indirect style, Walter goes to great, finicky pains to explain how working with these creeps will actually, like, save the ecosystem. Hey, doesn’t “eco” come from the Greek “oikos,” meaning “house”? Why yes it does! Must be some kind of parallel there–save the planet, save your house, save your fucked up family . . . Only none of that pans out; instead the section gets bogged down in a cluster of details that mingle with Walter’s increasing attraction (no, deep love and lust) for his twenty-something assistant. Meanwhile, his son Joey is growing up all wrong and fucked up, falling in with neocons who hide their war profiteering in a cloak of patriotic ideology. The democratic freedom we think we cherish is a lie; the personal freedoms we struggle to obtain–by escaping our fucked-up families–is ultimately a damning, soul-devouring curse. The American Dream is just morbid competitiveness.

If Franzen intended to write a zeitgeist novel, a How We Live Now novel, I wonder if this is this really what he thinks the spirit of our age boils down to? He gets many of the details of the last decade right, but the prose is bloodless and the characters are dull, unlikable, and unsympathetic. Of course, real people can be dull, unlikable, and unsympathetic, but that usually means that we don’t want to hang out with them, let alone read about their fears and desires for almost 600 pages. If our own families are dull, at least they are usually likable and sympathetic–at least to us, anyway (I love and like my family, in any case). Freedom feels like a novel with nothing at stake, or, perhaps, a novel where everything has already been lost, where outcomes are drawn null and void from the outset. And really, I wouldn’t mind all of that if it wasn’t so tedious. It practically buckles under its own sense of weighted importance in trying to reveal how Oedipal tension underwrites ideology. Oedipus might have been fated from the get-go, but at least there was some action and excitement in his story–some level of heroism, anyway. And because I’ve brought up Oedipus again, I’ll indulge myself and cite Talking Heads one more time.

In “Once in a Lifetime,” probably the group’s most famous song, Byrne sings, “You may ask yourself / Well, how did I get here?” The song’s narrator wonders if he can escape time, wonders if his suburban confine is a trap or a paradise; there’s a sense of sublime ridiculousness to it all, as if he might transcend time and space and contemporary life and take off “Into the blue again /Into silent water.” He’s trying to navigate the weird gap between suburbia and ecology, between duty and freedom. It is a song that at once recognizes the existential despair of a modern, suburban life, comments on its absurdity, and then surpasses it heroically. The song is undeniably about a figure in crisis, but that figure decides that “Time isn’t holding us / Time isn’t after us.” That figure is freer than the characters in Freedom, and freer still in his weird warp of ambiguity (a warp concretely codified in Byrne’s bizarre dance in the video). The hero of “Once in a Lifetime” transmutes existential absurdity into sound and vision; Oedipus saves his country (and provides the audience with catharsis) via his ironic, tragic self-mutilation; Patty and Walter kiss and make up. It’s a dreadfully facile ending, the worst kind of wish-fulfillment that seems wholly unsupported by the narrative preceding it.

But perhaps this is an unfair way to review a book that is apparently so important–to compare it to Oedipus Rex and a few Talking Heads songs. And I’ll admit that if Freedom had not been so wildly over-praised in the past few months, I’d probably try to find something positive to say about it. So I’ll try: Franzen is deeply intelligent, even wise, and his analysis of the past decade is perhaps brilliant. It’s also incredibly easy to read, but this is mostly because it requires so little thought from the reader. Franzen has done all the thinking for you. The book has a clear vision, a mission even, but it lacks urgency and immediacy; it is flaccid, flabby, overlong. It moans where it should howl. Nevertheless, the book is not a failure, at least not on its own terms. I believe that Franzen has written the book that he intended to write, that he has documented the zeitgeist the way that he perceives it–I just happen to find his analysis dull and his characters irredeemably uninteresting. Do not feel obligated to read Freedom.

Dashiell Hammett’s first published novel, Red Harvest, stars an unnamed dick, but the book isn’t so much a detective novel as it is an exploration of the destruction and renewal of a vice-ridden mining town named Personville. The city boss, who serves “Poisonville” as both mayor and company president, can no longer control the strikebreakers he imported to bust up a prolonged work stoppage. Initially retained by the editor of the daily paper to conduct background research for a developing story, the Continental Op is reluctantly hired by the mayor to return the town to respectability.

Red Harvest is no murder mystery in the Scooby Doo sense because, unlike the Spillane novels reviewed last week, there is no particular villain to unmask. Here, the action unfolds as the Continental Agency operative learns the personal histories of the town’s power players, assesses their motivations, and determines how best to play one set of guns against another. The simple brilliance of this novel is Hammett’s ability to create believable characters in a handful of sentences, and then send them out to wreak mayhem against others. Poisonville is as much a living character as Conan Doyle’s London or Bolaño’s Santa Teresa because it is so central to its citizens’ hopes, frustrations, and fears. The detective apprehends, as bodies multiply, that the town is somehow getting the better of him.

The Continental Op might just be a stand-in for Hammet’s ideal reader. Even though he’s privy to the same information we are, the detective is uniquely able to separate the relevant from the misleading and move the narrative forward. He ingratiates himself with each of the opposing camps in town, analyzes their situations, and dispenses advice to their leaders based upon their own best interests. Although the shakedowns, shootings, and betrayals were probably inevitable, the Op is the catalyst, the omnipotent narrator annihilating and rebuilding alliances. Our detective’s actions lead to more than a dozen deaths, a prison break, riots in the street, blackmail, and his own frame-up for murder.

Rarely do writers trust their lead characters to create, and not merely experience, their own story. I imagine that most characters, and most living human beings, aren’t capable or don’t want to always be in charge, preferring often just to passively accept whatever is foisted upon them. Hammett’s writing in Red Harvest is so precise and inviting that those who pick it up might convince themselves, as they flip backwards twenty pages or so, that they could have played puppet-master just as easily.

At New York Magazine, Charles Burns annotates a page from his excellent new graphic novel X’ed Out. See the slideshow here. A sample–

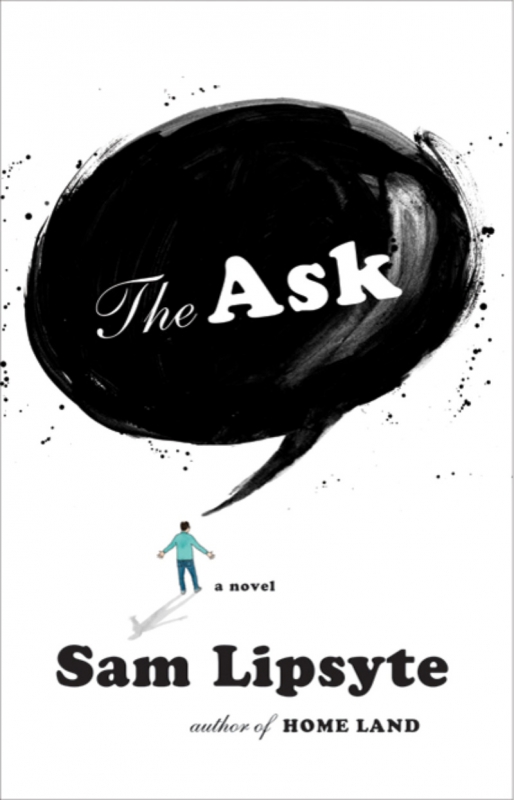

I listened to the audiobook version of Sam Lipsyte’s hilarious, wistful, mean, and devastating novel The Ask last week. I invented chores and took any scenic route available when driving to get more of the book faster, frequently laughing out loud, or grimacing, or even feeling weird and shameful pangs of remorseful identification with the book’s protagonist and narrator, Milo Burke. I’m going to do my best to unpack the book’s themes–particularly the way it simultaneously eulogizes, valorizes, and mocks the American Dream–but first I need to get something out-of-the-way, a mea culpa of sorts.

As I mentioned, I listened to the book, but I don’t have a copy, so, shamefully, I can’t really quote any of Lipyste’s marvelous sentences. He is a master stylist, capable of zapping our dead modern idioms with the kind of alarming twists that highlight just how vacant language has become. Lipsyte also has a gift for rhythm, tone, and cadence, and he’s a master of the deadpan punchline. While the sentences in his last novel Home Land sometimes felt overly fussed over, straining under their own polish, The Ask showcases an effortless style that both seduces and repels. Lipsyte reads The Ask audiobook himself, yet lets the tone and cadence of his words dictate the tone and timbre of his voice. It’s all very good. And you’ll have to just take my word for all that as I have nothing to quote now (I’m sure I’ll re-review the book when I pick it up in paperback, though).

The plot is rather thin: Milo Burke, who once aspired to being a celebrated painter, now works for the grants department of a mediocre liberal arts college. His job, essentially, is to beg wealthy parents and alumni to donate massive gifts of cash to the school — this is “the ask.” Or rather, that was his job before he got fired for losing his cool with the spoiled brat daughter of a major patron. This leaves Milo moping around Queens, drinking too much, and pissing off the wife he is slowly becoming estranged from. Which is a shame, because he’s trying to be a good husband and father to his young son; despite his own shitty childhood–boozing, philandering father, emotionally absent mother–Milo is doing his best to give his family the American Dream. He’s more or less abandoned his own dreams of being a painter, and along with it, the weird faith he located in the various theorists–Marxists, feminists, deconstructionists, etc.–who informed his art school years. Much of the novel finds Milo pondering not just on the value (or lack thereof) in his liberal arts education, but also on the friends and anti-friends who he slummed with in those days. Just as the narrator of Home Land dwells on his high school days, Milo Burke can’t quit thinking about his college years in The Ask.

That past returns in the form of Purdy, a rich kid who slummed with Milo and his druggy art kid friends back in their college days. Purdy is incredibly wealthy even after the stock market crashes of the late 2000s, and has Milo specifically reinstated by the university to officiate an intended “give” (the answer to “the ask”). Purdy’s real intention though is to turn Milo into a kind of bag man, a go-between to deliver large sums of cash to Purdy’s caustically embittered illegitimate son Don, an Iraq War vet who’s lost both his legs to an IED. This arrangement thrusts Milo into Purdy’s surreal world of privilege and power, but also puts him into contact with a deranged, maimed, and deeply, deeply hurt young man who will, essentially, change the way that he examines the world and his role in it.

I’m now going to gloss over much of the book: there are many, many very funny situations, strange characters, and wonderful little insights. And now that theme I mentioned: the death of the American Dream.

Late in the novel, Milo calls America “Dead America.” Earlier in the novel, he complains that America never got to be Rome; that America is a dying, crumbling empire that never even got to revel in its hedonist excesses. Milo is keenly aware that his own white, white-collar, privileged, urban existence as a liberal-arts-educated American puts him in a position of greater material comfort than 99.9% of the rest of the people in the world, yet this fact does nothing to assuage his despair–in fact, it exacerbates it. Milo is ashamed of his despair, too-cognizant of its implications. His shame becomes a meta-, self-referential shame, and it leads to Milo essentially surrendering any power or agency he might have claimed in the universe. His liberal arts education and his own sensitivities render him feckless and bitter, always grumbling over the cosmic injustice of modern, Dead America. He is a walking, rambling critique of power, yet–as his wife likes to point out–he never does anything about the injustice he perceives. It’s only after interacting with Don that Milo begins to see an inroad to agency.

Don is, it must be said, a miserable, caustic human being, a racist blackmailer, and perennially cruel to anyone who extends a hand. He’s also performed the most real “give” in the novel–he’s lost his legs for Dead America, sacrificing his own mobility and freedom (those constituents of the dream) for the freedom of others, or at least for the illusion of other people’s freedom. Don’s toxic behavior makes him utterly repellent and thoroughly anti-heroic, but in Milo’s identification with the young man–and in Milo’s willingness to lose financial security and familial stability by essential siding with Don over Purdy– there is a glimmer (just a glimmer) of redemption and agency for Milo. Don embodies everything about America that Milo (and presumably Lipsyte) hates, yet he has also answered “the ask,” both literally and symbolically. The novel invokes then not just scathing ironic attack on the American Dream, but also a pity that reveals an intrinsic (and perhaps childish) wish to believe, a wish to make Dead America live again. The novel ends with Milo reclaiming (or maybe just claiming) some degree of agency, beginning with getting back an old war knife his father had given him, a clear symbol of paternal, phallic power (the kind that his liberal arts education told him was bad, bad, bad). And yet there’s no resolution, no pat answers–how could there be? Instead, the novel ends in another crisis–not Milo’s this time, but Don’s. But I won’t spoil that, because, hey, you’re going to read this now, aren’t you? Very highly recommended.

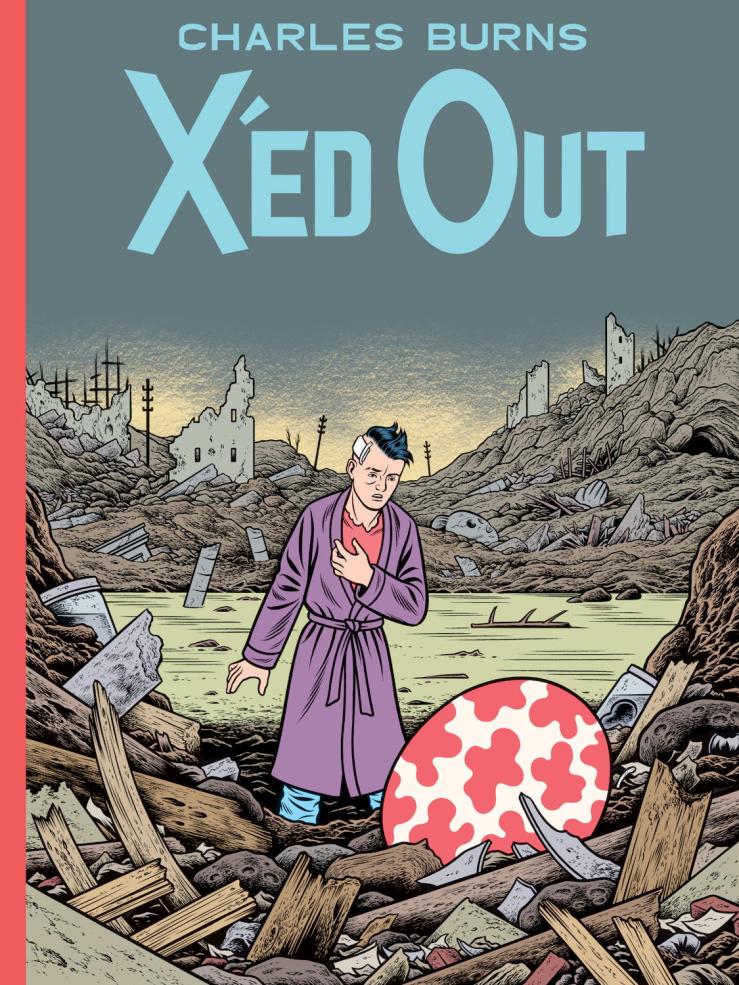

If you like Charles Burns, go ahead and pick up X’ed Out, the first (and very promising) entry in a new trilogy. Skip this review. You’ll probably be happier (and more unsettled) just experiencing all that vivid, glorious weirdness for yourself without any potential spoilers. If you need convincing, read on.

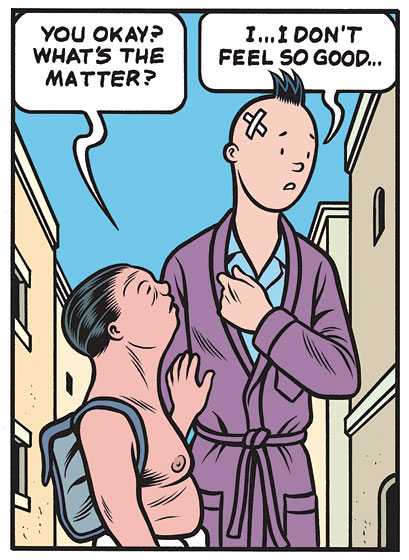

X’ed Out begins in a strange fever-dreamland that doesn’t immediately announce itself as such. Instead, we tentatively enter this weird world with Doug, the book’s protagonist, who, like Alice following the white rabbit, chases his (long dead) childhood cat through a crack in the wall. Doug traverses a cavernous, ruinous place, littered with murky detritus and swamped in a strange flood, to finally arrive in a bizarre desert town that approximates William Burroughs’s Interzone. Populated by mean lizards who dress like Mormon slackers and other grubby grotesques, the terrain readily recalls both Tatooine and Asian bazaars. Hapless Doug, still in pajamas, house coat, and slippers — and marked by an as-yet-unexplained head wound — soon finds himself under the guidance of a strange little diapered dwarf, who may or may not have his best interest in mind. The dreamworld unravels as Doug glances an old man — an “oldie,” as the dwarf says — who we will learn later is Doug’s father. An all of a sudden we’re back in the real world, back in waking life.

But no. That’s not right. Not “back” — we were never in the waking world to begin with. Significantly, X’ed Out begins in the Burroughsian dreamworld and then moves to a conscious, concrete reality. Burns’s dreamworld sequences explicitly reference Belgian cartoonist Hergé’s seminal Tintin comics (you can see how X’ed Out’s cover riffs on the Tintin adventure The Shooting Star here). Doug’s dream face is an expressive, stark mask, a naïve, cartoonish contrast to the bizarre nightmare to which it reacts.

Doug — the waking world Doug, the “real” Doug, that is — pulls a similar mask over his more realistically drawn face later in the story when he does his “Burroughs thing” at a slummy art punk party. Alienated from the scenesters who don’t get his cut-up poetry performance, Doug takes up with Sarah, a girl from his photography class with a thing for razor blades and pig hearts. The same night they meet, he loses his girlfriend, and her crazy boyfriend goes to jail for assaulting a cop. They initiate their romance in Patti Smith records, lines of cocaine, and sick Polaroids. Ah, young love.

But all of that is in another kind of dreamworld, the past, a retreat for the “real,” contemporary Doug, who spends his few waking hours cringing in his bathrobe, poring over old photos, and eating the occasional Pop Tart. At night he eats pain pills and goes to Interzone-land, a place that seems as real and solid and valid as his past with Sarah, a past he has apparently lost. Doug bears a huge patch over half his head (significantly x-shaped in his Interzone version), and both this wound as well as the psychic trauma he’s obviously endured (and is enduring) remain unexplained throughout X’ed Out. However, Burns’s often-grisly images hint repeatedly at a past event filled with violence and loss. X’ed Out leaves us in the Interzone, with the dwarf making long-term plans for Tintinized Doug. There’s even talk of establishing residency and employment–it feels like Doug is here to stay (at least in his non-waking hours). X’ed Out ends maddeningly with a girl who visually recalls Sarah being borne by lizard men to a giant hive. The dwarf explains that she is their new queen–and like some insect queen, she is a breeder. Yuck. The ending is the biggest problem with X’ed Out, simply because it leaves one stranded, wanting more weirdness.

In Black Hole, Burns established himself as a master illustrator and a gifted storyteller, using severe black and white contrast to evoke that tale’s terrible pain and pathos. X’ed Out appropriately brings rich, complex color to Burns’s method, and the book’s oversized dimensions showcase the art beautifully. This is a gorgeous book, both attractive and repulsive (much like Freud’s concept of “the uncanny,” which is very much at work in Burns’s plot). Like I said at the top, fans of Burns’s comix likely already know they want to read X’ed Out; weirdos who love Burroughs and Ballard and other great ghastly fiction will also wish to take note. Highly recommended.

X’ed Out is available in hardback from Pantheon on October 19th, 2010.

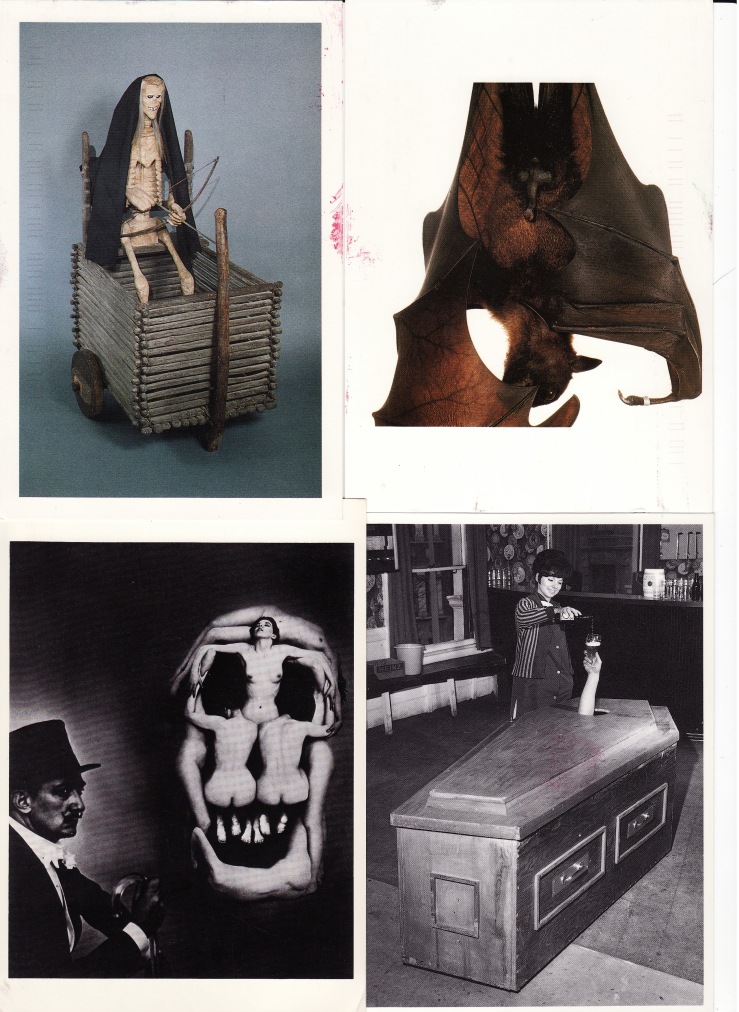

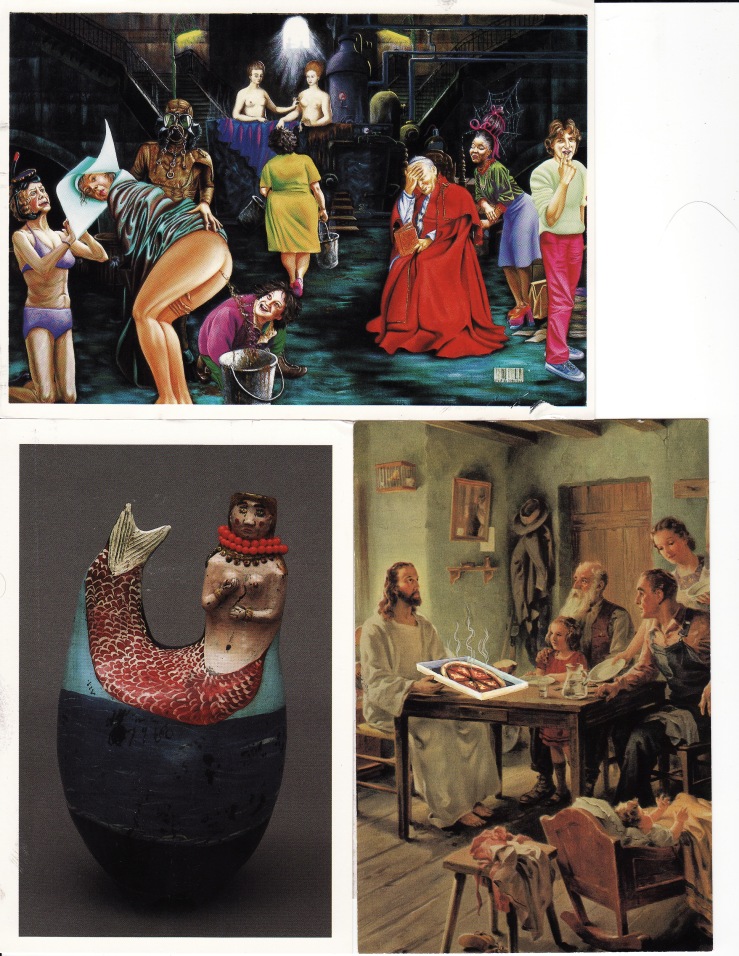

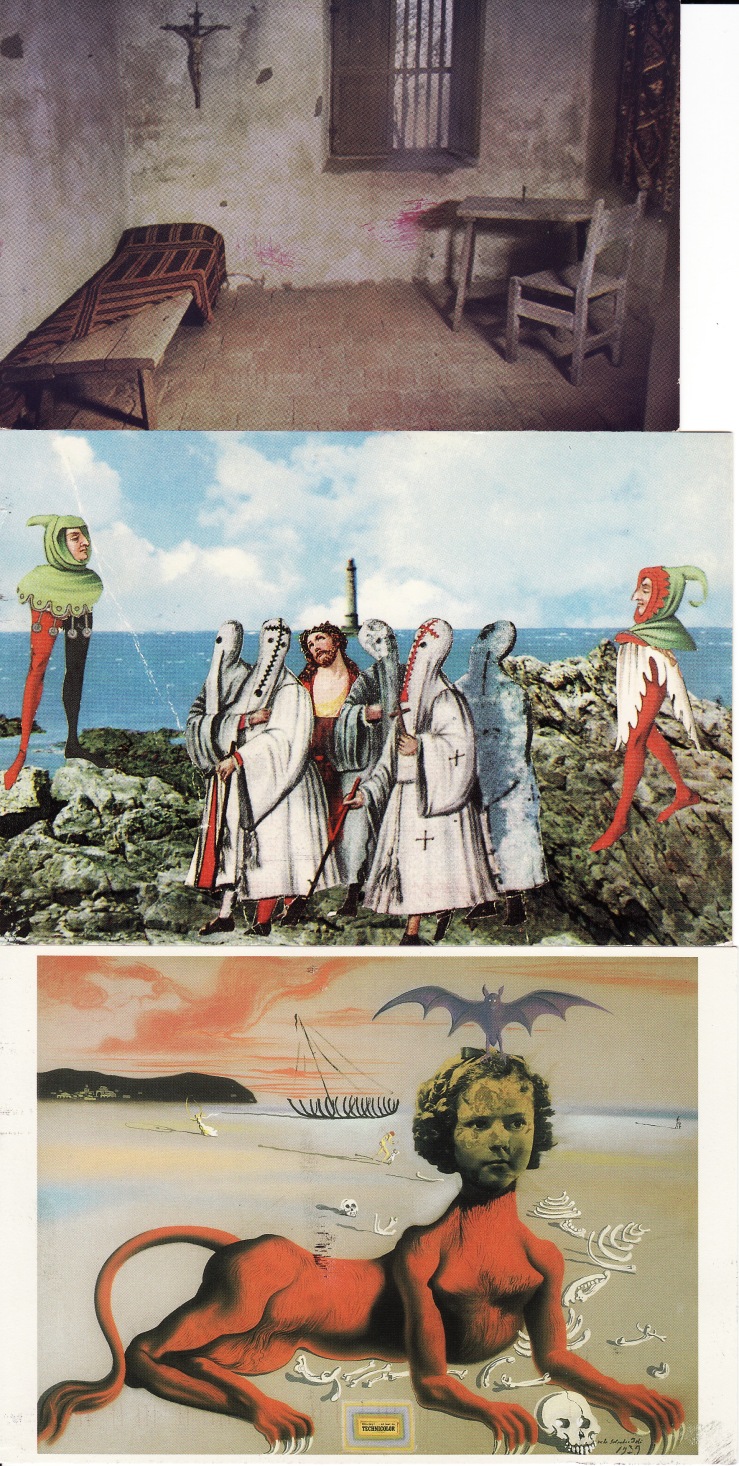

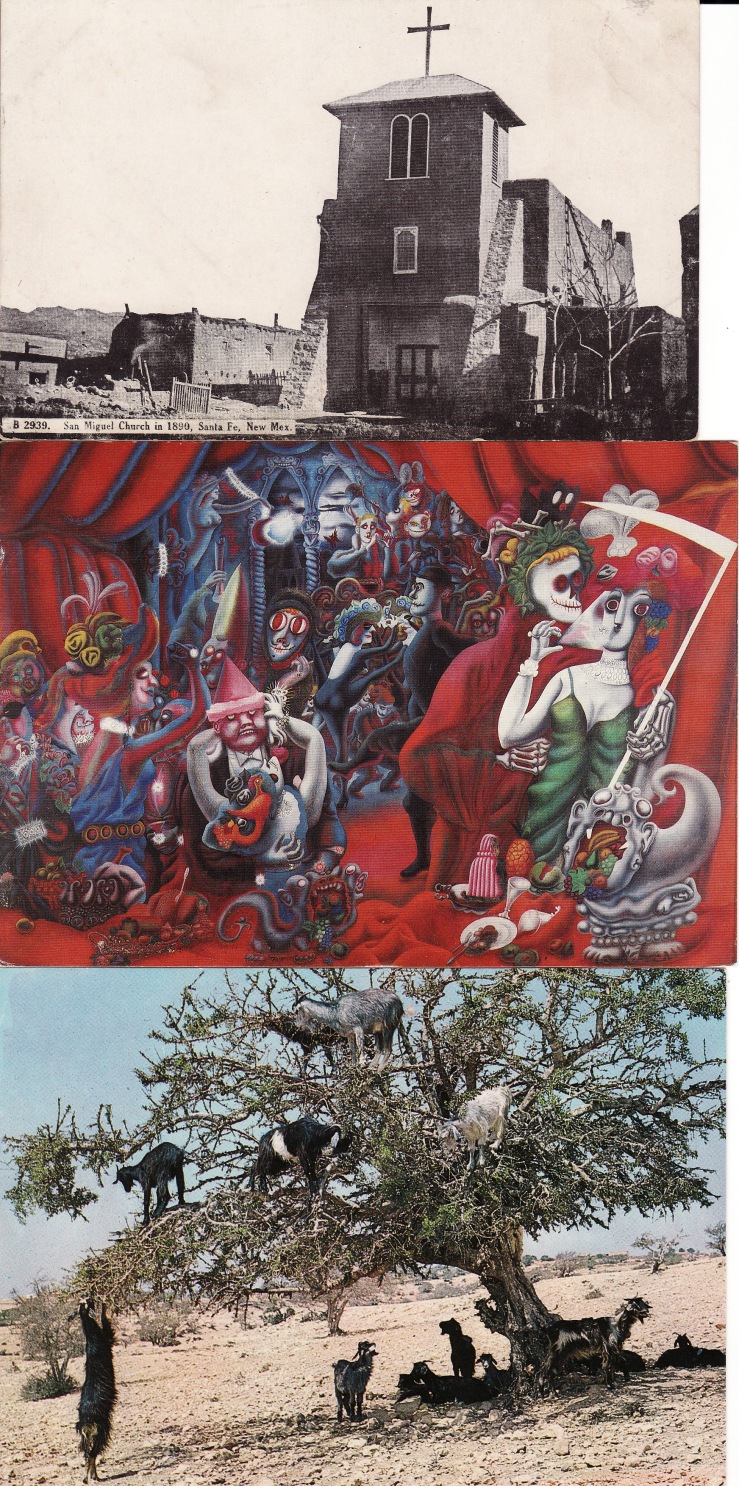

Big congratulations to Michael Cooke, a librarian from Flower Mound, Texas who is the winner of our Blood Meridian contest. Michael will receive a copy of the 25th anniversary hardback edition of Cormac McCarthy’s seminal anti-Western/awesome Western courtesy Biblioklept and Modern Library. Michael had the unfair advantage of being from Texas, and he totally cheated by sending in a baker’s dozen postcards, which was totally awesome. Cheating and being evil is the core of Blood Meridian. Each of Michael’s stark, garish, gritty, surreal, or just plain wicked postcards came with a wonderful corollary quote from the novel. The postcards come from Michael’s personal collection; he’s had some of them for years, and they’re from all over the place, several came from New Mexico, Cormac McCarthy’s chosen home. Here comes the weird–

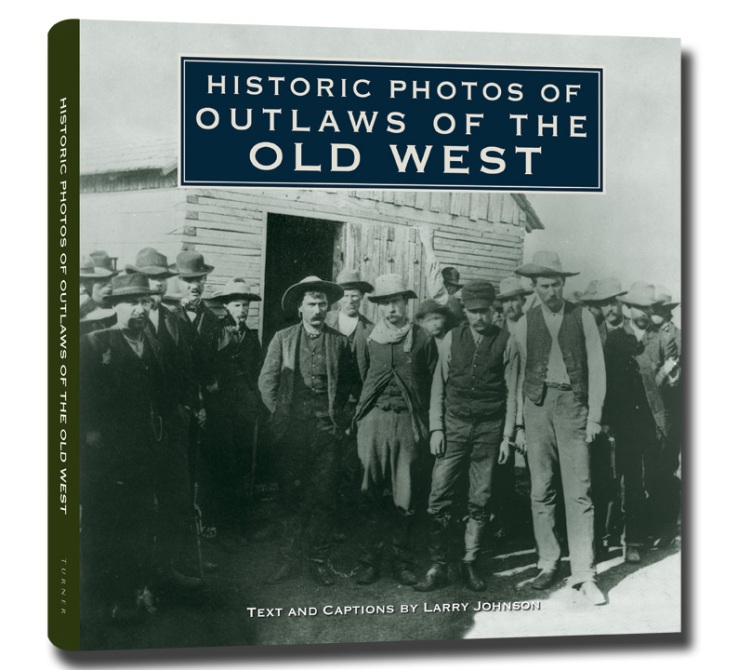

The romantic myth of the Western outlaw still remains central to American identity. If we are part Puritan, we also like to think of ourselves as the kind of anti-social cowboys who go out and manifest our own destiny. It’s no wonder that we have a tradition of valorizing outlaws like Billy the Kid, the Dalton gang, and Frank and Jesse James, transfiguring their bullying and theft into a kind of partisan resistance to hegemony. These men did not steal from the rich to give to the poor, yet we like to pretend that they were Robin Hoods. Turner Publishing’s new collection Historic Photos of Outlaws of the Old West presents 200 archival images of infamous (and not so famous) robbers, road agents, and rascals in the kind of gruesome detail that outlines just how awful these people really were. The Old West isn’t so romantic after all.

The romantic myth of the Western outlaw still remains central to American identity. If we are part Puritan, we also like to think of ourselves as the kind of anti-social cowboys who go out and manifest our own destiny. It’s no wonder that we have a tradition of valorizing outlaws like Billy the Kid, the Dalton gang, and Frank and Jesse James, transfiguring their bullying and theft into a kind of partisan resistance to hegemony. These men did not steal from the rich to give to the poor, yet we like to pretend that they were Robin Hoods. Turner Publishing’s new collection Historic Photos of Outlaws of the Old West presents 200 archival images of infamous (and not so famous) robbers, road agents, and rascals in the kind of gruesome detail that outlines just how awful these people really were. The Old West isn’t so romantic after all.

The book moves from the beginning of photography in the early 1850s to the unlikely end of an era, the 193os when the West Coast finally settled down and civilized (at least a little bit). Larry Johnson provides informative and unobtrusive text, letting the stark and often grisly photos convey the tone and emotion of the book. Simply put, this isn’t for kids. There are plenty of dead bodies, many hanging from nooses or laid out in a row, like this charmer of the Dalton gang–

Or how about Ned Christie, unfairly framed for the murder of Deputy Marshal David Maples in 1887, Oklahoma? This picture of Christie reveals that the emerging art/science of photography allowed for a certain fetishizing of the dead body–that the corpse, via mechanical reproduction, might somehow live on. Grisly.

We can see the same fascination with death in this famous image of Jesse James, who was shot in the back by Robert Ford while adjusting a picture. (Their complicated story is told in the brilliant revisionist film The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, by the way).

There are less famous but equally intriguing figures as well, like Benjamin Hodges, a black Mexican cowboy who made his living as a con artist in Dodge City. Here is the confident confidence man–

The images in Outlaws of the Old West are both fun and unsettling, and Johnson never glosses over or sugar coats the ugly truths behind these images (he even points out that, though we see the shootout at the OK Corral as a kind of archetypal battle between good vs. evil, the Earps and their pal Doc Holliday were hardly angels). The pictures in this book gel more with the imagery we find in revisionist Westerns like Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian or Sam Peckinpah’s bloody films, which is another way of saying that they aren’t for the faint of heart–and I enjoy that about the volume. Check it out.

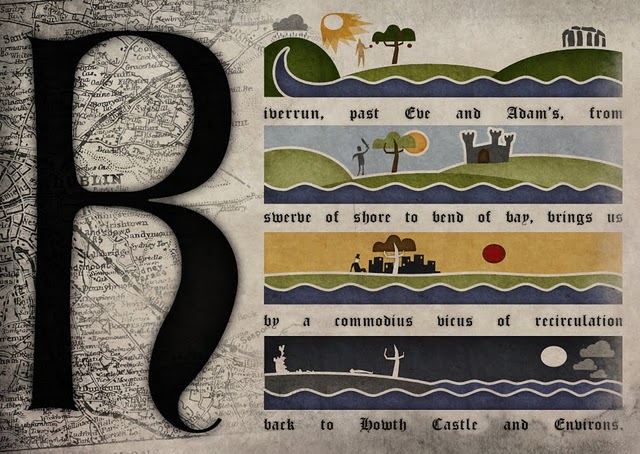

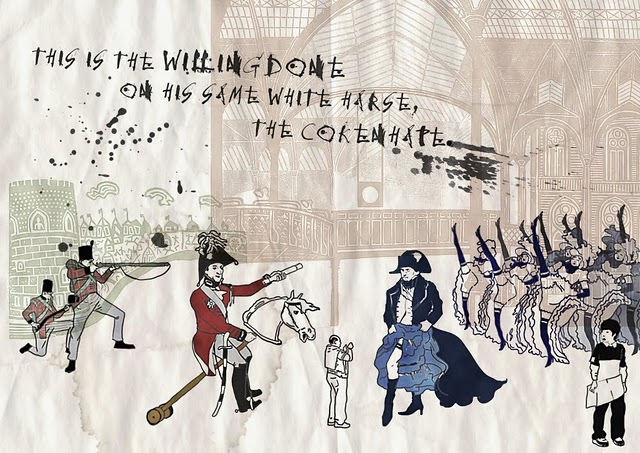

At Wake In Progress, Stephen Crowe has given himself the daunting task of illustrating James Joyce’s novel/linguistic black hole Finnegans Wake. It’s pretty cool stuff, and we love projects like these (see also: Six Versions of Blood Meridian and One Drawing for Every Page of Moby-Dick). Crowe’s site makes an interesting if different companion for the ongoing project at Ulysses “Seen.” Good luck to Stephen–keep them coming! (and thanks to @RhysTranter for sharing). More images–

Online auctions allow book-lovers to engage in what could be labeled “biblio-sharking.” Some poor sap needs to clear out his basement to make room for a foosball table or a Jacuzzi, and readers take his books for an extraordinary profit. While the seller may hesitate to dispose of their treasures, I’ll readily pay negligible sums to compensate him for his losses. So, if your rumpus room means more to you than fiction, please please please place your ads on Ebay.

Online auctions allow book-lovers to engage in what could be labeled “biblio-sharking.” Some poor sap needs to clear out his basement to make room for a foosball table or a Jacuzzi, and readers take his books for an extraordinary profit. While the seller may hesitate to dispose of their treasures, I’ll readily pay negligible sums to compensate him for his losses. So, if your rumpus room means more to you than fiction, please please please place your ads on Ebay.

Some poor mug did just that last week, allowing me to take home 18 detective novels for five clams and nominal shipping and handling charges. Because anthologies were included in the package, I scored twenty-four books for about thirty cents apiece. Ed Biblioklept, kept busy for weeks at a time supervising hooligans and future delinquents of America, has granted me permission to review one of my purchases, the New American Library’s collection of Mickey Spillane’s first three Mike Hammer novels—I, the Jury, My Gun is Quick, and Vengeance is Mine.

Spillane sold hundreds of millions of detective and spy stories during a long career, and the Hammer stories guaranteed him an interested and rabid following. Although private dick Mike Hammer finds himself in any number of slippery situations, Spillane’s central character, rather than any individual plot twist, is what makes these stories both convincing and compelling.

Spillane sold hundreds of millions of detective and spy stories during a long career, and the Hammer stories guaranteed him an interested and rabid following. Although private dick Mike Hammer finds himself in any number of slippery situations, Spillane’s central character, rather than any individual plot twist, is what makes these stories both convincing and compelling.

Hammer is the archetypal square-jawed detective, but he demands that you listen to his recollections of a case because he’s clever, resourceful, and vulgar. Although indelicate by today’s standards, Hammer is a tough guy for his times, beguiling dames who are used to getting just what they want, burning through decks of unfiltered Luckies, and drinking brandy for breakfast. What’s timeless, though, is his belief that bad guys are afforded too many protections by an impotent system of justice and that once all the pieces are put together, one extraordinary man performs a public service by putting a few slugs in the guts of murderers. In each of these stories Hammer begins unraveling the mysteries only after someone close to him has been killed.

This was the first collection of detective stories I’ve ever finished, and each page dragged me further into a black and white world filled with villains, vixens, and corrupt politicians. The reader becomes an unpaid extra in a B-level film noir.

This was the first collection of detective stories I’ve ever finished, and each page dragged me further into a black and white world filled with villains, vixens, and corrupt politicians. The reader becomes an unpaid extra in a B-level film noir.

Hammer explained to me, a snob, the enduring popularity of the literary detective: “You’ve forgotten that I’ve been in business because I stayed alive longer than some guys who didn’t want me that way. You’ve forgotten that I’ve had some punks tougher than you’ll ever be on the end of a gun and I pulled the trigger just to watch their expressions change.” Mind what you think.

The Guardian and other sources report that Howard Jacobson has won the 2010 Man Booker Prize for his novel The Finkler Question. The novel, which we haven’t read, is apparently a comic piece about love, loss, Jewish identity, and male friendship. The win is perhaps something as an upset, as many folks had Tom McCarthy’s C pegged as the favorite (last week bookmaker Ladbrokes even suspended betting on the Booker after bets on C crowded out the competition). Read our review of C here.

The Guardian and other sources report that Howard Jacobson has won the 2010 Man Booker Prize for his novel The Finkler Question. The novel, which we haven’t read, is apparently a comic piece about love, loss, Jewish identity, and male friendship. The win is perhaps something as an upset, as many folks had Tom McCarthy’s C pegged as the favorite (last week bookmaker Ladbrokes even suspended betting on the Booker after bets on C crowded out the competition). Read our review of C here.

Stephen Kotkin’s Uncivil Society earned rave reviews when it debuted last year in hardback; this week Modern Library releases the trade paperback version. Uncivil Society is a revisionist history that dispels the romantic myth that a “civil society” of dissenting citizens orchestrated the fall of Eastern European Communism (and its symbol, the Berlin Wall). Rather, Kotkin (along with colleague Jan T. Gross) concisely and methodically shows that the Eastern Bloc’s demise resulted from the corruption and incompetence of the ruling class of bureaucrats and ideologues–the “uncivil society” who borrowed massively from the West to buy consumer goods they could not afford. Kotkin finds case studies in East Germany, Romania, and Poland, but his analysis extends beyond these countries to indict the Soviet model.

Stephen Kotkin’s Uncivil Society earned rave reviews when it debuted last year in hardback; this week Modern Library releases the trade paperback version. Uncivil Society is a revisionist history that dispels the romantic myth that a “civil society” of dissenting citizens orchestrated the fall of Eastern European Communism (and its symbol, the Berlin Wall). Rather, Kotkin (along with colleague Jan T. Gross) concisely and methodically shows that the Eastern Bloc’s demise resulted from the corruption and incompetence of the ruling class of bureaucrats and ideologues–the “uncivil society” who borrowed massively from the West to buy consumer goods they could not afford. Kotkin finds case studies in East Germany, Romania, and Poland, but his analysis extends beyond these countries to indict the Soviet model.

Kotkin’s writing is direct and precise, stuffed with concrete facts and political analysis without sacrificing narrative integrity. In other words, he takes a murky subject and illuminates it. The narrative proper is slim at under 150 pages, making the book a quick and ideal survey of a widely misunderstood time. Students and politics of history will wish to take note of Uncivil Society, a straightforward and agile read.

More from The Paris Review’s vaults. In an interview from 1977, William Gass weighs in on the oral/aural aspects of literature–

I think contemporary fiction is divided between those who are still writing performatively and those who are not. Writing for voice, in which you imagine a performance in the auditory sense going on, is traditional and old-fashioned and dying. The new mode is not performative and not auditory. It’s destined for the printed page, and you are really supposed to read it the way they teach you to read in speed-reading. You are supposed to crisscross the page with your eye, getting references and gists; you are supposed to see it flowing on the page, and not sound it in the head. If you do sound it, it is so bad you can hardly proceed. It can’t all have been written by Dreiser, but it sounds like it. Gravity’s Rainbow was written for print, J.R. was written by the mouth for the ear. By the mouth for the ear: that’s the way I’d like to write. I can still admire the other—the way I admire surgeons, bronc busters, and tight ends. As writing, it is that foreign to me.

You may have noticed (and probably don’t care) that today is October 10, 2010, 0r 10/10/10 (or 10.10.10, or 10-10-10, or whatever iteration you prefer). But some people like lists. So, with very little thought put into the process, here are three literary lists to celebrate 10 Oct. 10–

Ten Ridiculous Character Names

1. Stephen Dedalus (A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Ulysses, James Joyce. Even Stephen ponders how ridiculous and overdetermined his name is)

2. Major Major Major Major (Catch-22, Joseph Heller)

3. Bilbo Baggins (The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, J.R.R. Tolkien. Sure, he’s a hobbit, but “Bilbo Baggins” is still pretty much off the silly scale)

4. Brackett Omensetter (Omensetter’s Luck, William Gass)

5. Horselover Fat (VALIS, Philip K. Dick)

6. Milkman Dead (Song of Solomon, Toni Morrison)

7. Humbert Humbert (Lolita, Vladimir Nabokov)

8. Lionel Essrog (Motherless Brooklyn, Jonathan Lethem)

9. Tie: Wang-Dang Lang/Peter Abbott/Candy Mandible/Judith Prietht/Biff Diggerance (David Foster Wallace suffers from Pynchon-fever in his début novel, Broom of the System)

10. Tie: Benny Profane/Oedipa Maas/Tyrone Slothrop/Zoyd Wheeler/Rev. Wicks Cherrycoke et al. — (Various novels by Thomas Pynchon. Yes, Pynchon should probably get his own list)

Ten Excellent Dystopian/Post-apocalyptic Novels That Aren’t Brave New World or 1984

1. Riddley Walker, Russell Hoban

2. Camp Concentration, Thomas Disch

3. A Clockwork Orange, Anthony Burgess

4. Oryx and Crake and The Year of the Flood, Margaret Atwood

5. The Hospital Ship, Martin Bax

6. Naked Lunch, William S. Burroughs

7. VALIS, Philip K. Dick

8. Ronin, Frank Miller

9. Ape and Essence, Aldous Huxley

10. The Road and Blood Meridian, Cormac McCarthy

Ten Movies Better Than or Equal to the Books On Which They Were Based

1. The Godfather

2. The Shining

3. The Thin Red Line

4. Children of Men

5. Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban

6. Trainspotting

7. No Country for Old Men

8. The Grapes of Wrath

9. There Will Be Blood

10. Jaws