” , ” , , ” . ” , ; ; , . ; ; . ‘ . . . . ; ; ; . ” … , ” . ” , ‘ ” ( , , , — — ) , ” ‘ ” — — ! . ” ? ” . ” ‘ . . . ” ” … , ” , , ” , , ‘ … . ” ‘ — — – , – . : : . , , . , ‘ , , – . ‘ , , , , , , . . . ” — — ! — — ! ” . ” , ” . , ; ; . ? ; ; , – . . — — — — ! – . . — — , — — . , , ‘ , , — — . ” — — ! — — ! ” . , , . ” — — , ” , , , , . ” — — , ” , , , ‘ . ” — — ! — — ! ” , . . , , , , , — — . ; — — . ” , ! ‘ … ” , , . . , , . , , . , , , . , , , ; , . . – , – — — ” , , ” — — . ! . . , , , , , , , , , . ( – ) , – , , , , . . . , , , . . . ” ! ! ” , . . . . . . . , , — — ‘ , , , . , – , . ” ! ” . , . ” ? , ! ! , . ‘ ? ! . , ” , ‘ . ‘ , . , , ‘ , . , . , . ‘ . , , – , – , . – ; , , , — — , , . . ‘ . ‘ . ; . ” , , , ” , ; ; , – , , . . , , , , . – ‘ . ; . . ” , ” . . ” ‘ , . ‘ , ” , , , , , , , . ‘ . . ” ? ” . ” ‘ , ” . ” , ‘ , ” , , , , , ‘ , , , , — — ? , , . . ” ! ” , . . . . ‘ ‘ . ; ; ‘ . . . ; – ; . ; ‘ . – – . , . , , . . . . . ” , ” . ” , . . , ” , ” . ” – ; ; . ” ‘ ? ” . ” ‘ , ” . . . ” , ‘ ? ” , . ” ‘ , ” . . ” ‘ . , , , . ” ” ‘ — — , ” , – . , – , . ” ? ” . , , . , , . , . – , . . . . . ” ? ” , . . . ” – , , ” . , ‘ , . . . , ; . . ; ‘ , . , , , , . ! , , ! , , . – . . . . . . . . ‘ — — , – . . ; . , . ; – . , , , , ; – . , , . ‘ . – . . . ‘ – ; – , ; , . ” . ” — — ” ” — — ” ” — — ” ‘ ” — — ” ‘ ! ” ” ‘ — — , . ” ” ‘ ‘ , ” . ” ‘ . ” ” — — . ” ” ; , . ” ( . . ) , , , , . – . ; , ; ; ; ; , ‘ , — — ? ? , — — , , ; — — , , , . , ‘ ‘ , , , , ‘ . ; ‘ . , ; ; , , , , , , – . ” , ” ; , , , , , , — — , . . , , ? , ‘ , . , ; , , , , , , , , , , ‘ , . ; , , , , ‘ — — . , . ” ‘ , ? ” . , ‘ , . ” ! ” . . – , , , . , , , . , , , . . . . , . , . . ; . . ; ; , , , . ; . ” ‘ , ” . . , , . , . , . ; , . — — , , . . , , . ‘ ; , , ; ; ; ; – ; . , , , . ; . ; ; – ; ; . ; ; . – . . . – . , , . . . , , ; . , , , , – , , ( ) , , . ; , . , ; ; . ; . . . . , , – , , , – , , , , , , , . ( ) . ‘ ; — — . ; — — ; — — ; ‘ — — ; . ? — — ‘ . , . ‘ . , ‘ , ! ‘ . – ; – ; . . — — . , ‘ ? . , ‘ ; , , , . ” , ” – , , ; ; ‘ . ” ‘ , . . , . . – ! – ! ” ” – ! – ! ” , , . , . ” ? ” . , . ” ? ” , . ” ‘ , ” . . ” ‘ — — , ‘ — — , ‘ . . , . ” ” , . ! ” , ‘ , . , , , . , , , , , — — — — , . , , , , . , , — — . ? . — — . . . . , . ” . , ? — — — — , — — ” . , . ” , – – — — — — ” ” . ” , . . . , – , – , , . . . ” ? ” , . ” ‘ ! ” , . ” ‘ . ‘ , ‘ . ‘ ! ” , . ‘ , . ” ! ” , . , , . ‘ , . – , – , . ‘ , ” , ” , , — — . , , — — . ” . , ” . — — ” ? ” , . , . ” … ” . . ” , ” , , , ; , ; . , ; , , , – , . – , ; ; , , . ‘ , , . : ” . ” . ‘ ( ) ; ( ) ; — — , , , — — , , , – , , . . ‘ — — , . , . . . ” , ” . , . , . , . , , ” . . ” . ; ; . , , . . . . ” , ” ( . ‘ , , ) . ” , ” . , , , , . , . – . . – ( ) . . . , , – . . . ; , . ‘ – . . . . . – . . . – . . , . ” . ” . , , . , , , , . . . . , . , , . ” ! ” . . , . , , , . , – . – . ‘ , — — , . . , . , , , . ; . . , . , , . , . , , . , . . , . ” ‘ , , ” , , ” ‘ – . ” . ‘ . , – — — , — — ‘ . . , – , . . ” , ” . , . , ” ‘ , , . . ” ; . , . — — ‘ . – , , , ‘ , – , ‘ – . ( ) , , , , . – — — ‘ — — , , – , . , . , . — — — — . ‘ — — — — . , — — . . . . , , ; ; , . . , . ; , . – , , – , . — — , . . , . . , , . , . , . . , . . – , . , , . . . . , , – , . . . . , , , , , . ” , ! ” . . ” – , . , ” . , . ‘ , , : ” – , . . ” . . . ? : ” , , ! ” . . , – , ; , , . , , – , , , , ‘ , . ‘ . , , , ‘ , . — — — — , , , , , … , , ; , , , ; , , ; ; , ; , , — — . , , , ” … … . ” , . ” . , , ” . – . , , , , . . ? . ” ” , ? ; , . , ” . . . , ” , , , , , , – , , . ” , ” . , , ” ‘ ‘ ‘ , ‘ ” … . , , , – . . ” , , ” . , – , ” ‘ … … … ” , , – – , , , , , , , . , – . . ; , , , — — . ” , ” , ” ‘ . . ” . . ” . … , … , , ” . . . , . ” , ” . ” . ” ” , ” , . ” , ” . , , ” , . ” ” , ” . ” ? ” . , . ” , , ” , . , , , . ” – , ” . , , . . , , , . – , – ‘ ( , ) . – , , . , . , . ; … . . ? — — . ( ) , ( ) , . . . , . , , , — — ! , , ! , , , ‘ . , … , … , , … — — — — . , . – — — . , . — — — — … . . . ‘ . ( ) : ” , ‘ ” ? : … . , , , — — — — , , , , , ? . , , . . , , — — , , . , ‘ – , , : ” ” ; . ” … ” , ; , . , – , , , – , – . . , , , , , , , . — — ‘ — — . . , ‘ , , , ? , ? , , , . , , , . . ; ; . , , , , , , . , , . — — – — — . ; , . – ; , , . … — — , , — — . , , . , ‘ ? – — — ; — — . — — , . , . ‘ — — ? , ( , , – ) , – . , — — , ; , – – . . , , , , , ( — — , ) , . — — , , , , , . . , , ‘ . . ‘ ; ; , , . ” , ” , . , , , – , . ” , ” . . ” . ? ” . ; , , , — — . . . . . . , , , , , . , . . , , — — . ” , ” . , , , , , , . , . , , , , , , , — — — — ” , , ? ” , . ” ‘ , , ” , . . . . , , . . , , , — — . , . . — — . , . . . . — — ? , – , , – ? ? ; , , . , , . ” , ” , ” . ” . – , . . ‘ . , . , . ; – — — — — . ” ‘ ‘ ! ” . , , . ” , , ! ” , . ” , ! ” ” ! ” , — — . ” , ” , – , — — — — , — — ! , , ? , , ? . . . — — . , , , . ; . . , , , — — — — ; ; ; ; ‘ ; — — ” , , ” . . . — — — — — — — — — — , , , , , , , — — , , , , , . , , , , , . , – . — — ; , , – . ‘ ; , , . , , , . , , ; ; , , , . . ” ‘ , ” . , . , , , , — — ‘ . , , , . ” – – – , ” , , , . ” – – – ! ” , . ” ‘ ‘ , ” . ” . ” . , . , – , , , … ” ‘ , ” . ” ‘ , ” ( , ) . ” , ” . ( . ) ” , ” , . ” ? ” . ‘ . ” ‘ , , ” . ” , , ‘ ! ” , , . ‘ . , , . ” … … ” . , . ; ; – . , . ‘ , , ‘ ; ; ; ‘ . , . ‘ , , . , . ; , , ; , – . . ‘ . ; ; , , ; ; — — , — — ” ? ” ; ; ‘ , , . , ; ; ; ; ; . , ‘ . , — — . , , , , ‘ . . , , – . , ; . – , . [ – ; , ] , , , , , , ; , . , , , ; , . ; . , ; ; ; . ‘ ; — — , , ; . , , , , ( ‘ , , ) , ! ! ” . ” ; . , , ; ; ; ; . . ‘ . , , , , – , , , , , , , . . ‘ , , , , , , , , , , , . — — . , . , , – , . , , ; ; . , , — — — — ‘ , . , ‘ , , . ” , . ‘ . , ‘ ? ” , , , , , ” ” — — , , , , ; , ; ; , ; . . ; — — — — , , , , . . , ‘ , , , , , , — — ‘ . . , , , , . , , , , ; , , , , . — — — — ? ” ? ” , , , , ‘ , , , , , , , , , , . . . , , , , : ” , ? ” — — , , ‘ . , , , . , . , , . , , , , ; , . , — — , , , , , . , , , , , ‘ , , — — . ” ‘ ‘ , ” , , . , , . . . ? – , , , , , , , , ; . ; . , . , , , , . . ? . , , , , ; , , ; ; , — — , , — — ; ; ; , , . : ” — — ! — — ! ” , , , , , , . . , – , ; , , ‘ . . — — , . , — — , , , , ; , , , , , . ? — — — — , ! ‘ . , , , , , , — — , , . , , , , — — , ; , , , , . , , , . ; , . . , – , ; , , , — — . , – , — — — — . . , . , , , . ? ? ? ? , — — , ; , . ‘ — — , , , , – . . . ; ; , – , , . , ? . . . ; ; , ( ) ; ; – ; ; , , , . , , , , , , , , , , . , – , ? ? ? , . . ” … … . ” ? , , ; . ” ” — — . , , , , . , , , , . ” . ” ‘ . . . ” , ” . , . , , . ” , , ” , ‘ . ; . , . . . — — , , , . , , , , , , ‘ . ‘ . . – . . . , , , . , , , , : ” — — — — – . ” ‘ , , – ? , , , . ! – – . , , , , , , , – , . , , . , ; . . , , , , . , ; ; — — . – . . , . , , , , , . . – – … . , . . , , . . . ; — — — — ? , ; – – ; , , , , . ; , , ; ; ; , , , ; . . , , , , , , , . , , — — ! . . , ; . , , , . , — — , , — — , , . , . , , , , , ; , , – , , , , . , , . , , . , , , . ; , , . , – . ? . . , . . . ‘ , , ‘ , ; . ( ) … . . ‘ . ‘ . ‘ , … . ‘ . ” … ” . . , , , ; . ; ; , , , . , , . ; . – . . ” ‘ , ” . . ” … ” . ; – . , , , , ? ” … ” . ” , ” , . ” . ” , , , , , — — , — — , , , , , – , , , ‘ , . ” , ” , ” . ” . ” ‘ ‘ ? ” . ” , ” . ” , ” . ” , ” . ” , ” . ” , ” , ” . ” ” ‘ ‘ , , ” . ” ‘ , ” . ” — — ‘ — — ” ” , , ” , . ” ‘ … ” . ” ‘ … ” ” ? ” . ” — — – , ” . ” ‘ , ” . ” ‘ , ” . ” , ” . ” ‘ . ” ” . ” ” ? ” . ; , , , . / * ” : ; ; , , ” * / . ” / * , ? ” * / . ; , , ; , , , . / * ” , , , ” * / . , ; ; . / * ” , ” * / , , , , . ‘ ; ; – – ‘ , ‘ , , . , – ; , , . . ; , , , . , . . . ‘ . , , , … , , . . ; . , . . . , , , – . ; ; , . , , , ‘ , , ‘ . . ” — — . ” ” , , . ” ‘ . , . . , . , – . , . , , . , , . ‘ , ‘ ‘ , . , . , , . , , . . , , , . , , , , , , . , , . . , , , , , , ‘ , . ‘ . , ‘ . , , . , . … . , . , – . , . , , , . , , . ‘ . . . ” . ? ” . , . , . . . ” , . , ” . , . ‘ . . . ” , ” . . ” … . , . ? ” – . , , . ; ; , , . . . . . . ( ; ) . . . . . . . ; . . . ; ; ” , ” . . ” ‘ — — ‘ , ” . . . . ‘ . ” , , ” ; ; . . , , . . ; ; , , ; . . . , . . . , , . . . ‘ . . , , , . , . , ; , ; , , , . . ; . . – ; , , . , , . ; – . . . . . , , , , , . – , , , — — — — — — — — . , , , . , , , , . , , – , . . , , , , , . – . . – ! , – . , , – , – – . ‘ . . . . , , , , . ” , , ! ” . , , ” , , ” ‘ , . . ‘ , . : ” , , . , ‘ ? … . ” , , – , . , , , – , . . . . ” , ? ” . ” . ‘ . ” . . ” , ” , ” … . ” , , . ” ? ” . ” . ” . . ” , ” , , . ” — — . . , . ” , . . ” , ” . . . , . ” , . , ” . ” . . ” ” — — , . , ” . ” ; , ” . ” , . . ” ” , ” . . ” ‘ , ” . ” … ” . ” , ” . , . . , , , ; , , , , . . ” , , ” . , ‘ . ” ? ” . ” ? , ” . . ” , . ‘ . ” ” ‘ . ” . . ‘ . , , : ” , , , … . ” ” , ” , . . . ” , ” . . – . ” , ” . ” , ” . , . ” … . ? ” – . ” , ” . ” , ” . ” , , ” . . ” , ! ‘ ! ” , . ” , ” , . . . ” ! ” . . ” ! ” . . , . ” … ” . ” ‘ … ” . ” , ” . ” , ” . ” , , , ” . ” . … ” . ” ‘ , ” . . . ” ‘ , ” . ” . ” ” ? ” . ” , ” . . ” , ; , ; , ; … ” . ” , ” . ” , ” . ‘ . ” ? ” , . ” ‘ — — ? ” . ” , , ” . . ” ? — — . ” ” , , ‘ , ” . ” , ‘ . ” ” ‘ , ” . ” , ” . ” ? ” , . ” ! ” . – . . . , , – . . . ” ; , ” . , . . ‘ , . ” , . , ” , , . . ” , ” . . , ; . ” , ” . . ” , ” . ” . ” ” , ” . . ” , ” , . ” – . ” ” … ” , … ” , , ” … , ” , ! ” . ” ? ” . ” , ” . , , . ” , . ” ; . . ” , ” … . ” ‘ … ” . ” , ” . , , . ” ‘ . ” ” ! ” , . ‘ . ” , ” . . ” ‘ — — ‘ ! ” . ” ‘ ! ” ” ‘ , ” , . . ” ! ” , . – , , , . ; . ” , ” , , , ‘ . ” , ” , . ” … ” , ” … . ” ” , ” , . ” … ” , ” , , ” , , . ” … … ” . . ” , , ” , . ” , ” , . ” , ‘ , ” . ” , , ” , ; . ” ‘ — — , ” , , . , , . , . ” ! ” . ” ? ” . ” , , ” . . ” , , , ” . , , – , . . , . ” – , ” . ” – , ” . ” – , ” . : ” – , . ! ” ” . ! ” . , . ” ! ” ” , , ” . . ” , ” , . ” , ” , , ” ‘ , ” , . , , – . ‘ , , , . ; . — — , ‘ — — ‘ , — — . , , , – , , . – . , , . ” , ; , — — , ! ” . ‘ . . . . ‘ . ‘ . . . ; , , , — — ” , ” ” . ” ; , , , — — . , ‘ , — — , . , , , , , . ‘ , , . , , , , … . ? . . , , . , ‘ ; ; . . . , , . — — . ‘ , , . ‘ , , . , ‘ , , , , , , , , … . , , . ‘ . ‘ , . ” ‘ ? , … . ‘ ‘ ? — — — — … . ? , ! ” — — — — … , , , , … , , ; . . ‘ , , ; ; . , ‘ , , ; , – , , , . . ; ; ; ; ; , . , , , , – , . ; . ; . , . , , , . , , , , ‘ , . , , , , ; . , , , , , . ” — — ‘ ” — — . — — , , , — — , , , , , , . – ‘ , , , , — — , — — , , , , ‘ , , , . . ; , , , . , , , , , , ; ; ; , . , , . , , – – – – — — , , , , . ” ? ? ? ” . ‘ . . . ; ‘ . . , . , ( ) , ; , — — , ( ) , . – , , , , – , . – , , ; , ; . , , ; . , ‘ , ; , ; … … , . , ; , , , . . . — — . — — ; ‘ ; , ; ; ? , ‘ , ‘ — — ‘ — — ; , , , . — — . ! , ; , : – ; . , – – , , . . ” ! ” . ” ‘ ! ” ; , . ” ; , ” , . . . ” ! ” , ; . , , , , , . , ; ; ; . . . , . — — , , , ; , , — — ‘ , , . . , , – . . . — — – — — . ( . ‘ , . , ) , , . , ; , ‘ , . . , – , … . ” ” — — . ” – . ” ” , ” , ” – . ” . , , : ” ” ( ) . ” ” … , , , , , , . ? – . ? ( ‘ ) . — — , . . ? ” , ” . ” . , , ‘ … ” . . . , ! ” , , , ” , , ” ‘ — — ‘ ” — — ? . , ‘ , , , , . . ‘ . , , ‘ , ” , ” , ‘ … . . ” , ” , : ” , . ” . . . ‘ ‘ , . ; ‘ . ; … . , , – . , . , . , . , , , . , — — , , , — — ? . . . ( ” ‘ – . ‘ . , . — — . — — . ” ) ” , , ? ” ( ” . — — — — ‘ . ” ) ” ‘ , . , … . ” ( ” . , , . ‘ . ‘ . ! ” ) . ” ? ” ( ” ‘ ? ” ) , – , ‘ . — — — — — — — — , – , , . , — — ; ; ; . — — , , ‘ , ‘ , , , ‘ . . , , , — — , , , ; ( ) ; . . ” , ” , ‘ , . ” , ‘ . ” . , , . ‘ . . — — ; ; — — . . ” ‘ . ‘ ! ” . ; . , ‘ . . . , – . . — — – . . , . . . , , , , , ; ; . ‘ , , – , – . , , , ; ; ; . ” , ” , , ” ‘ ! ” — — , ; , . – . ‘ ; , . , ” ” . – . , , , . . ” ‘ ! ” , , . , , , . . . ” , ” , , , ” . ” . . , , – . . ; , . ” , ” , ‘ – – , ” . ” — — , — — ‘ , ‘ ‘ , ( ‘ ) , ‘ . — — . — — ; ? , , . , ; ; , , . . . , , , , . ” , ” , ” . ” . , – , . . — — — — , , , , , , , , , , , , ; ; . . . , , ” , ” ; , , – … . . . . , , , ; ; . . . , , . ; – . , . — — , – , , , , ‘ , . ‘ , . , , , , . , ‘ ; , , . , , , ; , , . ? , : . , , ; , , ; . , , , . – . , ; ; ; ; , . . . ; ; ; ; ‘ , , ( ) , – . . , , . . , , ; ; . ‘ . . , , . . ( ) , — — — — ; , , , , , — — , . ; ; . , . ? . . , – ; — — , , , , , . . , , . . – . – . . . . , . . . , — — — — , . . , . , , , . , – , . . . . , , , , , . : ” ? … … . ‘ … . , . ” . ” . ‘ … . , ‘ ? … ” . ; . – ‘ , — — — — . ? , ‘ . ” ‘ — — … ” . ” ‘ ‘ , . ‘ . ” ; ; . ” , … ” . . ” – … … … … ! ” ! . . . . . — — ” , , ‘ . ! ? , ! ‘ , . . . ” . — — . , . . . . . – . . ” ‘ , ” . , , . ; ; . ? ? , ? ? . , , , , , . , . ; ; ‘ ; ‘ . ? — — . , . ! ‘ — — . , , – . , , , . . . , . , , , , , , – , , , , , , . ” ‘ , ” . . . . – . , . , , ; . . , . . ‘ , , , , ; ‘ , . , , . . , , – , – , , , ” ‘ , ” , , . . . – , . ; , . . . . , , . , , , . . ; ; . . , . ; ; ; — — . , , ; — — ‘ , , ‘ . . ‘ ; , , . . — — — — . . . . , , , . ‘ , ‘ , , . , , . . ; . , , , , , — — , , ‘ . ; , ? — — . . . ; , , . , . . , , – , – , . ‘ – , , , , . ‘ , , . , , , , , – , . . , , : / * ‘ , * / , , . ! , , , . ” , ” . , , — — . . . . ; , . ” , ” . ” , ” . . ” , ” . , , . . ” , ” , , ” ‘ . . , ” , . , , , , ” — — , . ” ” , ” . , ” . ! . ” ” ‘ ? ” , . ” … ? ” . , . ” … ” . . ” ‘ , ” . , ” . ‘ . . ” ” ! ” . ” , ” . . ” , ” . ” , ” . ” , ” , , ” . ” ” ? ” . . ” , ” . . ” . ! ” , . ” . . , . ? — — , — — , . . ! , . ! ” ” ‘ , ” . . ” , ” . ” , . , ‘ … . ” ” ‘ , ” . . ” , ” . ” … . . , . ” ” ? ” . . ” , ” . ” ? ” . . ” , ” . ” ? ” . . ” , ” . ” , ” . . ” ? ” . . ” … ” . ; . ; ; , . ” — — ” . . . , , , : ” ! ” ” ! ” . ” — — . ” ” , , ” . . ” . ” ” ? ” . ” — — ‘ … ” ” . , , ” . ” — — ! ” . ” ‘ , ? ” . ” . ” ” ? ” , . ” ? ” . ” , . ” ” ‘ , ” . ” , ” , . ” , . ‘ , . . ” ” ‘ , . , ” , . ” ‘ ? ” / * ” ? ? ? ” * / . , . ” , ” , , – . / * ” , ; . , ” * / . ” ! ” , ; ; . ” ? ” . ” , ” . ” ? ” ” . ” ” . . . . , . . … ” . ” ‘ . . ‘ ? , , — — , — — , , — — , , , — — . . , . , . — — , ” , . . ” ? ” . . ” . , ” . ” . ” ” , ” . . ” . , ? — — — — . . , ? ” . , , . , . ” ? ” . ” , . . , ” . . – . . , , , , , , ” . — — . . — — . — — . ” ” , ” . , . . – , , , , , , , . , , , , … . ” , ? ” … ” , . ” … , , ; – ; ‘ ; ; : ” — — — — — — , ” , , , , . , ; , , , , , , – , , . , ‘ , , — — ‘ , , . , , , , , ‘ , , , — — — — ‘ , ; ; , , . . ” , – ? ” ; ” ‘ , . . . , . , , ‘ , . ‘ . , , . , . . — — ” . . , , , ( , , ) , ‘ , ” , ” — — . . ; , . , , — — , , , – ‘ . . ” , ” , . ‘ ; ; ; ; . ; , , , , , ; . , , — — , — — ? — — , , , . ‘ . , , , , , , ; ; ; , , . ; , , , , – – . . – . ; , , . , , . – , , . , , , . , , , , , . , — — , , , , . . , , . — — , – , , , , , . , ; ; – — — ‘ . — — , , , — — ‘ ‘ . , , . , ‘ ; ; . , . , — — . , , , . . ” , , ‘ ? ? ; … . ” . . , … , – , ; ? , , — — ? ? . . . ” , ” , , , , ? , , ? , , – , , , , ? ; , , , — — ? — — . , . . . – . , , , – , ( ) , , , . ! ; , . . . . ; . ; . ; , ; , , . ‘ . — — . , , , , , . . . . — — ; — — — — . , , , – , . . , , , – , – , ( ) . ‘ . . . . , , , , . . ; ; ; ; . ; , ; , , , , . . . ‘ , ; — — , , ; — — , ; . ” ‘ ! ” , ‘ ? , . . , — — ‘ . , , . , . . . , . , . – . . … . . ; ; – ; ; ( , ) — — , , . ” — — , ” . , . ; . ? ” , ” . , , , , , , , , ‘ , ‘ ‘ , ( ) ‘ , , ; ; – , , , , — — . . . , . . ‘ , ( ) . . . – , . ; . . . ; . . . . . – . ‘ , , . . — — — — , . , ‘ ? . – . . , . . , , , . . – . – . , , . . , , . – . , — — . ; , , , . . – , , , , ‘ , . ; ; — — , . , , , – , — — ? . ? — — , ‘ . . . , . , , . ( ! . . . ‘ . ) . . . . , , , ; . ! , , . ‘ . , . , , . . . . — — . . , , ‘ . – ; , . — — . . . . . ‘ . . … . ‘ ‘ … . , , … . … . … . … . … . . … . . . . , , , . . . . . ( , ) , . , , ; ; , , . ( ) , ; . , , . ; . , . . ‘ . , ; . – , ; – – ; . , , . , , ‘ , . ” ? ” , . ” ‘ , , ” ‘ . , . . ” ” — — ” ” — — . , . — — . , , , , . , , , , . . ‘ , , , , , , . , , ; ; , , , , : ” ! ! ! ” – , , . . , , , , , , . ; , , , , ” , ” , , , , . , . . . , , , . , , , ; ; , – — — . . , , , . , ‘ , . . ; ; , ? , : : ” , ” , ” ” ” ” ” , ” ” . ” ; . ( , , ) . ” ” — — , , , — — – . ( ” ‘ , ” ) . ” , ” ; ” ” — — , . ” , ” , , , — — — — ; , , — — — — , . ” – ‘ , , ” , ; , , . . . ” , , ” , . , , , – , . – . — — , – . ” , ” , . ‘ , ‘ ? . , , , , , , ‘ , . . ” , ” , ” . ” , , , , . , , , . ‘ . ” , ” . . . . . . . ; ; . ; . ” , ” . , ‘ ; ; ; . ” , ” . ” , ” . ‘ ; ” , – — — ” ” – , ” , . ( , , ‘ ? ) ” ” — — ” ” — — ” , ” . , . ? . , ? , , , , , , – ( , ) , , , . , , – . ” ? ” . ” , ‘ — — . ” ” ‘ , ” , . ‘ , … . , . — — – . . , , , . , . ‘ , , , . . ” ‘ ‘ , ” . ” . ” ” ? ” . . ” – ? ” , – . ” , ” , . ” ‘ , ” . ” , ” . , . . . . ; ; . , , ( ) , , , . , . ” ” ‘ , . , – ; ; , . . ‘ ‘ . . , , – , ? , , — — , , . , . , ” , ‘ , ” , . — — ( ” ! ” ) , . ‘ , , ” , ” , . , ” — — . ” , . . , , , , , . — — , , ‘ . — — — — , , , , , , , . , — — ! . , , . . . . ‘ . — — — — ” , ” , ” ‘ ? ” ! , . , , , . . ? . . ; , ‘ . ‘ . . – ; , – . ? , — — — — . , . , . . . . ‘ . . . . . . , , , . . , , . – , , , , ( ) , ( ) . – . , , , . . . . — — , ! , , . . . . , , , ; , , , , . , , . ” ‘ , ” , . , . , . . — — , . , . . . . . . , , ; , , ; , . ‘ – ; – . . ; . . ( ‘ – ) ‘ , , . — — , , , . , , , — — . – . . . — — , , ‘ , . ; – . , . ; . . , , , . ; . – , , – , , — — , , , , . , . ‘ ‘ ; , , , , ; ; . , ; ; ; , ” ! ! ” ‘ . . . . , , ‘ , ‘ ; , ‘ . ; , , – , , ” ! ” , , , , . . , , , , ( ) , , , . . ‘ . ‘ ‘ , ‘ , , . , , , , , ; ; , , – , . , ; ; . , , , . ? ” ‘ . ” ” ? ” ” . ” , . . ‘ , , ‘ , ‘ , , , , : ” , , ‘ . ” … , . ‘ . , . , , , , . ; . , . ” ” , . , , , ‘ ‘ . , , , , . . – . , ( ; ) . ” ? ” , , , , , . ” , , , ” , , . . . ” , ” ( ) . , , , – , . – , ‘ , , ‘ . , , , , . — — , , … . . ‘ . , , , , , . ( ) . , – , . . , , . ; ; ; . , . . – ; – ; ; , , , . , . , , – – . . , – . , . . , , — — . . . , , ‘ . , . ; . , , , , , . , , , , , . . . . , . . . , , . ; . ‘ , , . – . ? ? , , , , . . . ; ; — — . , , , , , , , , , . . – . . ‘ . , . , . , . . , , , – , , , , ‘ , , , . , . , – , , , ‘ . . . , , , , . ‘ . , , . , . . ; . ; ; ; ; . . . , . ” , , — — , ‘ , ” , , , . , , , . . , , , , . . , , . ; . ; . . , , . – . ; , . , – , , , ; ; — — , , . . , – , , . . , , , , . , ; ; ; . , , , . . . . . . – . ” , ‘ , ” . , , , — — , , , . ‘ , , , , . . . , , . . . , , . , . ‘ . . . , . . . , , , , , , , , , . ” , , ” , . ” , ” . ” , ” . . . , – , : ” ! ” . , , . , , , ; ; ” ‘ , ” . . . , , , , , . . , , ( – , ) . , , , , – ; , — — , . . ” , ” , . ‘ , , , , ? , , , , , , . – . , . . — — , ; ; . . . . , , . . , , , . , , . . , , , . . . – . . . ; . ; . – . . . ‘ . , . , . . , , , . , . , — — ‘ — — – . , , , , ; — — , . ! , . . . . ” , , ‘ , ” ‘ . ” ‘ , ” , ; . ” , ” , ‘ . . ” , ! ” . , – . ” . . . . ” . ; . . . . , , . . ? , , , , – . ” ? ” . , . ” . . , ” . . . , , . , . , , ; ; ; ; . , , , , ? , . , , , , , , , . . . . — — . . . , , , , , . ” , . ” ” ‘ . — — ” , , , , , . ” , ” , – , – , , ” ‘ ‘ ” ; . ” ‘ ! ” . ” ‘ , , ” , – . — — ‘ ! ‘ , ‘ ? , ; , , – ” ? ” . ‘ . . . — — , – . — — , . , ‘ ‘ . . . ‘ — — ‘ , . . , , ; – ! . . ; . . , ; – , , — — , . ; ; , , ? ” , ” , . . ‘ , , — — . ( ) . . ‘ — — ; , , — — – , , – . . , , . . , . — — , – . , . – ; ; ‘ , , , ; . , , ; , , . . . ” , ” , – – . , ! . ; ; ( ) , – , , . , . , , , — — . . . . . ” ‘ ? ” . ” . ” – ; ; . ? ” , ” . – ? . ; ; ; . — — . ” ? ” . ” , ” . , , . . — — . . . . . , , . . . – . – , – – . . ; . – . . ? . . . , , , ( ) , — — . ” , ” . , ” – . ” ( , ; – ; , , ) , , , , , , , , . . – , , . , . . ( , ‘ , . ) ” ‘ , , ” , , , , . ” , , ? ” , , . , , . ” ? ” . ” , , ” . ” , ” . . ” ‘ , ” . ” ‘ . ‘ ” … . ” ‘ ‘ , ” . ” , ‘ . , ” . ” , , ” . ” . ‘ , . ‘ . . ‘ , ‘ ” , , – . ” , – ! ” . ” ‘ , ‘ ” , . ” , ” , . ” ? ” ” – , ” . ” , , ” . ” , ” . ” . . . ‘ ? , . , ‘ ? ” ” ‘ , , , ” , , , ‘ . ” ‘ , , ‘ ” , . ” – – … . , ” . ” ‘ . ” . , . ; , . ; ; ; . ” , , ” , ” ‘ ‘ . … ” … ” … . ‘ . . — — , . ” ” ‘ , ” , ” . , ‘ , . ” . ” ‘ , . ” . ” , ? ” . ” ‘ , ” , . ” , , ” , . ” ‘ , ” . ” ‘ ‘ , ” , . ” . ‘ . ‘ . ‘ … ” . ” , ” , . ” ‘ … ” , , , , . ” , ‘ . . . . . , … . ” . ” ‘ — — ‘ , ” . ” , ” . ” ‘ . ” . ” , . , . . , . . ‘ . . . — — ? ‘ . – , . ” ” ? ” . ” ? ‘ . , … . ” ” , ” . ” ‘ ? ” . ” , . ” ” … ” , . ” … ” ” , ‘ , ” . , . , ‘ . ” ! ! ” . ” ! ” , – . ” , ” , . , , . . . . – . , ! – , . , , ; ; ; – . , , – . . ” ? ” , . ; ; . ” ? ” , . ” , ” ; . , . – , , . ” ‘ , ” , . ” ‘ , ” , . ” . . — — … . ‘ ” ; . . ” ‘ , ” . ” ? … , , ‘ . — — ‘ ? — — ‘ . ‘ . — — … ” ” , ” , . ” ‘ . ” ” , ‘ , ” , . ” ‘ . ‘ . ” ” , ” . ” , ” . ” ‘ , ” , . ” ‘ . , . ” ” , . ‘ . , ? ” ” ‘ , ” . ” ! ” . ” . ” ” , , ” , ” ‘ . ” ” , ” . ” , ‘ . , . . . ” ” — — – ” . ” ‘ , ? , . . , — — ‘ . ” , , , ; . . . . ‘ . , , , , . — — . , , , ; , — — ; ; , , , , , ; ; , , . , , , ‘ . , , , , , , , . . , — — – ” ‘ , ” . , . ” … ” . , , , ” … . ” . . , ; ; . ” , ” . , , . , . ” , ” . . ” . ” . . ” ? ” . . ” , ” . . . ” , ” . , . ” ‘ , ” . ” , . ” ” , ” . . ” , , , ” . . . — — . ; . ” , ” . , . , , . , . ” ! ” . . . , . . – . . ; , , . . . . . , . . , ? . . , . , , , . ” , . , — — ” . . , ? . ‘ – ? . , , , ? . . – ” , ” , . , , ” , ” ” . ” , , , , . . , , , — — , . . , , . , , – . . , , , – . – , – . , , , . , . , , ” ! ” , ; , ; . . . . . , , . ” … , ” . , , ” . . ” ” , ” . . . . . . . . ‘ . , , , . , , — — ? ? , , . — — . , , . , . — — . ; – , . ‘ . . – , , . , . , , , , . , . , – , . . . . . , – – , . , , , , . , , . , ‘ . , , . — — — — . , . , . ” , ” . ” , ” , ” , ” . . , . — — . , , , , , , . . ; – . . — — . – , . , , — — , . . , . , . … . — — — — ‘ … . ” — — , ” , , — — , , , , . , , . ” ! ” , ” ! ” . – , . , ; ; ; ; ; ‘ ; ; ; . – ; . ? , , . , , , , , . ‘ ; — — — — . . . ( ) — — , , , , — — ; — — . . ; . — — , — — ; ” ” ; , , ; , , . , , . , , , ; ; . ” ‘ ‘ , ” . . . . . . – , — — — — , . , – , , , , , , . . . , , – , , , , . ” – , ” , . ” . ” , , . , , . . , , . — — , ? — — . , ‘ — — , , — — , . ; . ? , — — , , , , , – , . , , . , , , ” , ” . , ” ” ; . . , – , . ” , ” , ” . ” ” , , ” , . ” ‘ , ” , . , , , , , , , ‘ . ” , ” . ” . ” — — ‘ . , ‘ , , . . ‘ . — — ‘ , , , , ‘ . ‘ . , , , , , . — — , , ‘ , . . ” , ” , ” — — ” — — , . . ; ; , . ; — — , . , , ; , . ; ; ‘ ; . ; . . , — — — — ? — — — — ” , ” , , ” ‘ . ” , . ; ; ; — — — — , , , — — . . ” , ” . , ” — — — — . . , . , ” , , , . ” . ” — — — — , , , . ! . . . . . , , , , . , , . , , , . ; . ” , ” . . . , , , – . ” , ” . . ; ; ; . ; . ; . ” , ” . . ” , ; … ” ” , ” , . , . ; , , ; – – , — — , , , – , , — — , . ; . , , ; – , , , , . ” , ” , . . . ‘ . ” , ” . . ” , ” , . ( ” , , ” . ) . , ; . , , . , ( , ) , , ( , ) , . , , , . ” ! ” . ” ? ” , . ” , ” . ” . ” , , . . . ; . ( — — ‘ ? ) ‘ ; ; ( ) ? ” , ” , ” ” — — , , . , , – – , . . . . ” , ” , ” , ” . : ” . , , . ” , , , ” , ” . . . ; ; , , , . , , , , , . — — , , . ‘ . . . . , . , , , , — — ‘ . . . , , , , , , . . . , , , , , , , . ” , ” . , , . , , . , — — , , — — ! ! ! . ” , , ” , ‘ . ‘ , , , . ” , ” , ” . ” ” , ” . ” . ” ” , ” . , ‘ , , , , . – , , . ; . ” , ” . , . , . ” ‘ , ” , . ; , , , , ” ‘ . ” ; , , . ” ‘ , ” . ” ‘ – – ‘ ; … ” . . ; ; ; . ; ( , – , , , , , , , , – , ) , , . , , . ” ! ” ( ) . ” ! ” ( ) . ” … ! ” . , . , . ! ; . . ” , ” , , . . , . ; . . , . , , , , , ; , , ; , , . ; , , , ( ) ; , , . , , , , , , , , , . . , , , , , . . , — — , , , — — ; , , ( ) . , , , , ; , , , , . ” , , , ” , . ” , ” – . , . ; . . . , . . ” ‘ , ” . ” . ” ” ” , , — — — — — — ” ‘ — — — — ‘ — — , , , , ” — — , , , , , , , ‘ , . ; ; ; ; , , , , . ; , . . . ; ; . . ‘ , , , , , , . . ? . . . , , , . , ; ; ; . ( — — . ) . , , — — — — ; , , ‘ . . . ; ; , , — — ? . . ; . ! , , . , , , — — , , , , ; , . ” — — ! ” . . ” , ” , , . ( , ; . ) ” , ” , , . ( , , . ) , , , – . . , . , . , , , , , , . , , , , . . ; – ; , , , . — — ( . ) ‘ ; ; ‘ — — . ” ! ” , , , , , , ; ; . ” , ” , , ” ? — — ? ” , , , , , , , , , . , , , , , — — . ( . ) — — , , , , . ” , ” . , — — , , . , , . ; , ( ) ; ; , — — , ” , ” , ” . , . ” , — — ( , ) — — . . . . ” , ” , , , ” . . ” ” ? ” . ” ‘ . ” ” , — — . , ‘ . , ” , , . ? – ? . , , . , , . , , . . , ; , . , ‘ , . – . , — — , . ? , ( – ) ‘ , , ; , – , ‘ — — . ! , . , , — — . ‘ . . — — . ” … ” . ” , ” . , ” . ” , ‘ , . ” , , ” , ” — — . ” . — — , ‘ . ” ? ” . ” , , , ” . . ” ‘ . ” ” . ” ” , ? ” ” , ‘ . ‘ . . ” ” , . , ” . , , ” . ? , . ” . , , . — — — — – , , , , . , . ( , — — ) . ; ( ) . , , , , , , , – . , , , , , , . . , . , – ; , , – . . , , . ; . , , — — . ” ? ” , – , – . ” ? ” . . , , ; . , ( ) . ” ! ” , . , ” ! ” . . . . , . ‘ . , . ; ; . . . , , , . , . ” , ” . , . , — — — — , , , . — — . . . ” ? ” . ” , ” . , . ” , ” , . . . ” – , ” , , . . , , – : ” , — — ‘ ? , — — ? ” , , , , , , — — . , , . – , . ” , ” . ” . , … . … . … . ” ” , ” . ” . ” ” ‘ , ” . ” , ” . ” – . ” ” , ” , . . ” – , ” . ” ‘ – — — ? ” ” ? ” ” , ” . ” ? ” . ” . ” ” , ” . , , — — . ” , ” . ” — — . ? — — ! ‘ . . ” . ” ? ” . ” , ” . — — — — ? . ” ‘ , ” . ” — — . ‘ — — ! ” . ” … ” . ” , , ” . ” , ” , ” ? … . ” ” , ” . ” . ” . , . . . , . — — . ” , ” . ” . , ” . ” , ” . . ” , ” . ” . . ” . . ” , , ” . ” , … ” ” . ” ” ? ” . ” ! ” . . ; ; . , ; . , ; , . ” ‘ , , ” . ” — — , ” . ; — — . . , , . , , , . ‘ . ” , ” . ” . ? ” ( . ) . . . — — — — — — — — . . . . ; . , . – , . ‘ , , , , — — , ! — — . . . ; ? ; ; ? , ? , . ‘ – . ‘ . . , ( ) , – ; , , . . , , , ” ? ? ” ” ? ? ” , , – . , , ‘ : ” , ? ” — — ‘ . ” ? ? ” , ; ; , , – – . — — . . . , . , . , , , , . — — , , , — — . , , ; . ‘ , . ‘ . ‘ . , , . , – , — — , , . , , , – – , — — . , – , , , ? . ” , ” . , . – , . ( ) , , ” , ” , , , . . ( – ) , , . , , , . ; ; ; ; ; . — — — — , ; ; . ; ; ; ; . ; ; – . . , ; – ; – ; . – ; ; ; , , , , ‘ , ; ; ; . ” , ” . ; ; . , , . ” , ” . ; , , ; . ” , ” . ; , ; , ; ; , , . ” , ” . ” ” , , , , , , . ! ! ; ; ; , ? ” , ” . . , — — ; ; ( ) . ” ? ” . ” ? ” ” ‘ , ” . ” ‘ . , ” . ” ? ” ” , ” . , ; ‘ . ” ! ” . . . , , , , — — , ! — — , , ; ; ; ; . ‘ ? ‘ — — ‘ — — ‘ ? ? . , . — — — — , — — , ” ” — — . ” ! ” , . — — — — . , , , — — — — ” , ” ( ) . — — , . . — — , . , , ; , , , . ” , ” , . . ” , ” . ” — — – ” . . ” ‘ , ? ” . ” ‘ ? ” — — , , . , , . , . … , — — . ” ‘ , ” , ” . ” ? ? , , . ” ! ! ” ; . , , ; ; ‘ ; , — — ? — — . . . , , , . ; – . ” , ” ; . ” , ” , , , . ; . ‘ ; . ( ” ! ! ” . ) ” ‘ , ” . ” , ” . . ; ; , , . ” ‘ … ‘ ” . ” , . ! ! ” — — — — — — . ; . ” , ! , . ! ” , , , , , . ” – ! ” . – . ” – ! ” — — , , . , , , , , , . ; ; , , . ; ; – ; ; ; , , , . ‘ , , , , , , . , , . . . . . ‘ . , . ; ; ; ; , — — , , , ; , , . ; , , – , , . , , . ; ; , , . ; ; — — — — . , , . ; , , , ; . . . ” ‘ , ” , . ” . ” . , , , , , . ? , ( ) . ” , ” , ” . ” . . . ” ? ” , . ” , ” , – , ” . ” . ; , . ” ‘ , ” , . — — ? ” ! ” , – . ” , ” . ” ? ” ” , , ” – , . ” , , ” . ” . . . . ” – – , , , . , , , , ; . , . , ‘ , , . , , , ‘ , . . — — , , , – . ( ) , , , ; , , ; , , ( ) – , , , ; . ” ‘ , ” , , , — — ; , , , . ” . , ” . ” , ” , , . ” . ” . ” ? ” , . , , , . ; ; ; . ; , , – , , , , , , . , , , . ; — — ; ; ; ; ; , , . ; . – . ; ; ; ; ; ; . , ( ) , , , . , , , – , , , , – , . , , – . — — , – , – — — . , , ; , ; , , , , , , , , ; . , , , . , ; ; – ; , , , , , . , , – . , , . , , ; ; , , , , . ? , , . . , – , . , , . ” , ” . . ” ‘ ‘ , ” . ” . ” ; ; , , . ” , ” . , , ” … ” ” , ” – , ” . ” ” — — ” , ‘ , ” — — ? ” , , — — ” , ! ” . ; ; . ” ‘ , ” , , ; , , . , , . , , – , , – . – , ‘ . . , . – , . . , , , , . ” ! ” . , . ” ! ” . . ” ! , ” . . ” ‘ — — , ” , . . . ” ? ” . , . . , , ; , , , , , , , — — — — ( ) ; . ‘ . ; ; – ; ; , , . . – . – ; ; , , , . . . , – , , , , . , . . ” ? ” , , , . ” , ” . ” . ” , , , . , ; . ? ? ? . . . ” , ” . ” . . ? ? ” , ‘ . . , , . , ; ‘ . , – , . – . ” , ” . ‘ . . . … . , ; . – , . . ‘ . ‘ . , , , . . . ” ! ! ” , . . ” ! ” , . . ” , . ? ” ‘ .

Virginia Woolf’s Jacob’s Room, but just the punctuation.

In his

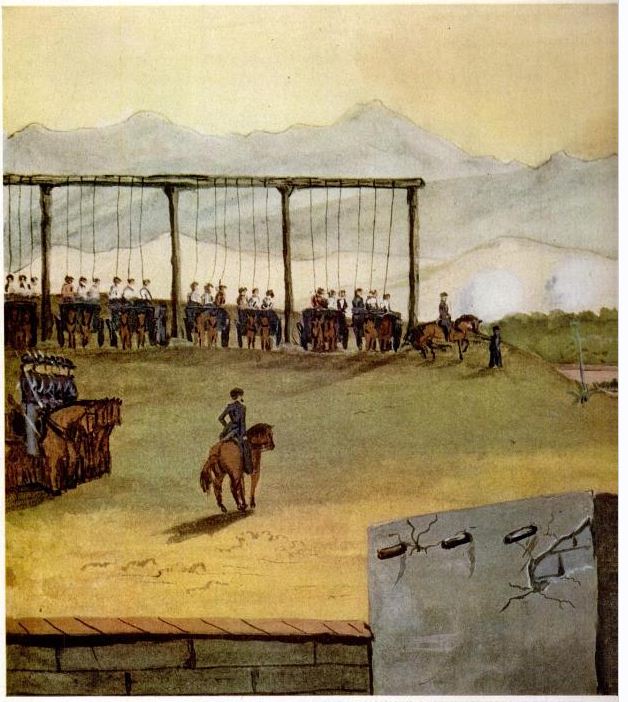

In his  According to Chamberlain, John Glanton was born in South Carolina and migrated to Stephen Austin’s settlement in Texas. There he fell in love with an orphan girl and was prepared to marry her. One day while he was gone, Lipan warriors raided the area scalping the elderly and the children and kidnapping the women- including Glanton’s fiancee. Glanton and the other settlers pursued and slaughtered the natives, but during the battle the women were tomahawked and scalped. Legend has it, Glanton began a series of retaliatory raids which always yielded “fresh scalps.” When Texas fought for its independence from Mexico, Glanton fought with Col. Fannin, and was one of the few to escape the slaughter of that regiment at the hands of the Mexican Gen. Urrea- the man who would eventually employ Glanton as a scalp hunter. During the Range Wars, Glanton took no side but simply assassinated individuals who had crossed him. He was banished, to no avail, by Gen. Sam Houston and fought as a “free Ranger” in the war against Mexico. Following the war he took up the Urrea’s offer of $50 per Apache scalp (with a bonus of $1000 for the scalp of the Chief Santana). Local rumor had it that Glanton always “raised the hair” of the Indians he killed and that he had a “mule load of these barbarous trophies, smoke-dried” in his hut even before he turned professional.

According to Chamberlain, John Glanton was born in South Carolina and migrated to Stephen Austin’s settlement in Texas. There he fell in love with an orphan girl and was prepared to marry her. One day while he was gone, Lipan warriors raided the area scalping the elderly and the children and kidnapping the women- including Glanton’s fiancee. Glanton and the other settlers pursued and slaughtered the natives, but during the battle the women were tomahawked and scalped. Legend has it, Glanton began a series of retaliatory raids which always yielded “fresh scalps.” When Texas fought for its independence from Mexico, Glanton fought with Col. Fannin, and was one of the few to escape the slaughter of that regiment at the hands of the Mexican Gen. Urrea- the man who would eventually employ Glanton as a scalp hunter. During the Range Wars, Glanton took no side but simply assassinated individuals who had crossed him. He was banished, to no avail, by Gen. Sam Houston and fought as a “free Ranger” in the war against Mexico. Following the war he took up the Urrea’s offer of $50 per Apache scalp (with a bonus of $1000 for the scalp of the Chief Santana). Local rumor had it that Glanton always “raised the hair” of the Indians he killed and that he had a “mule load of these barbarous trophies, smoke-dried” in his hut even before he turned professional.

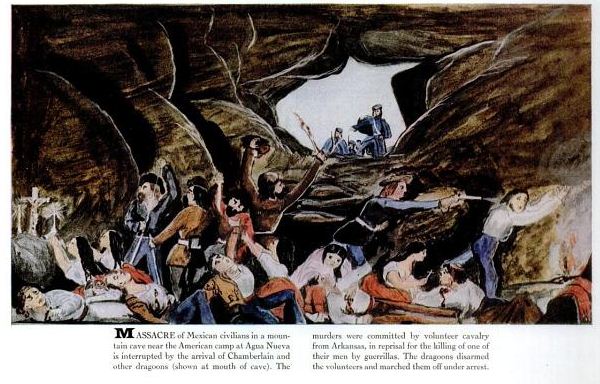

It’s fascinating to note how much of the Judge is already there–the pedophilia, the marksmanship, the scholarship, and, most interesting of all, the lack of hair. Confession goes on to detail the killing, scalping, raping, and raiding spree that comprises the center of Blood Meridian. Chamberlain even describes the final battle with the Yumas, an event that signals the dissolution of the Glanton gang in McCarthy’s novel.

It’s fascinating to note how much of the Judge is already there–the pedophilia, the marksmanship, the scholarship, and, most interesting of all, the lack of hair. Confession goes on to detail the killing, scalping, raping, and raiding spree that comprises the center of Blood Meridian. Chamberlain even describes the final battle with the Yumas, an event that signals the dissolution of the Glanton gang in McCarthy’s novel.

Content aside, Chamberlain’s prose also seems to presage McCarthy’s prose. In his book

Content aside, Chamberlain’s prose also seems to presage McCarthy’s prose. In his book  You can view many of Chamberlain’s paintings and read an edit of his Confession in three editions of Life magazine from 1956, digitally preserved thanks to Google Books–here’s

You can view many of Chamberlain’s paintings and read an edit of his Confession in three editions of Life magazine from 1956, digitally preserved thanks to Google Books–here’s