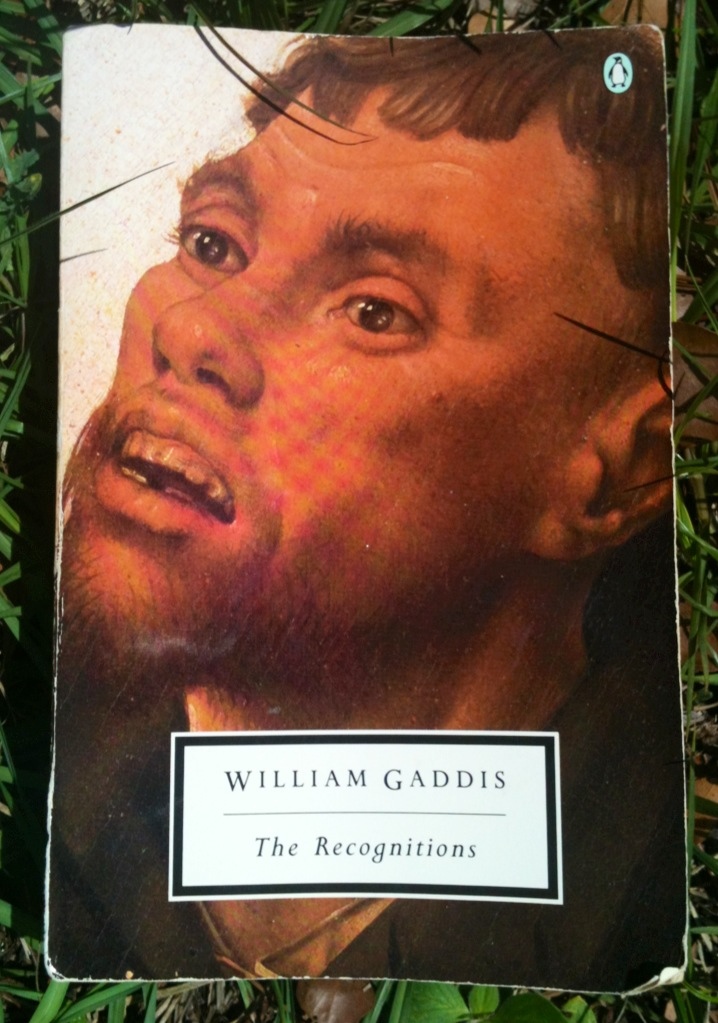

- I finished reading William Gaddis’s enormous opus The Recognitions a few days ago. I made a decent first attempt at the book in the summer of 2009, but wound up distracted not quite half way through, and eventually abandoned the book. I did, however, write about its first third. I will plunder occasionally from that write-up in this riff. Like here:

In William Gaddis‘s massive first novel, The Recognitions, Wyatt Gwyon forges paintings by master artists like Hieronymous Bosch, Hugo van der Goes, and Hans Memling. To be more accurate, Wyatt creates new paintings that perfectly replicate not just the style of the old masters, but also the spirit. After aging the pictures, he forges the artist’s signature, and at that point, the painting is no longer an original by Wyatt, but a “new” old original by a long-dead genius. The paintings of the particular artists that Wyatt counterfeits are instructive in understanding, or at least in hoping to understand how The Recognitions works. The paintings of Bosch, Memling, or Dierick Bouts function as highly-allusive tableaux, semiotic constructions that wed religion and mythology to art, genius, and a certain spectacular horror, and, as such, resist any hope of a complete and thorough analysis. Can you imagine, for example, trying to catalog and explain all of the discrete images in Bosch’s triptych, The Garden of Earthly Delights? And then, after creating such a catalog, explaining the intricate relationships between the different parts? You couldn’t, and Gaddis’s novel is the same way.

I still feel the anxiety dripping from that lede, the sense that The Recognitions might be a dare beyond my ken. Mellower now, I’m content to riff.

- I read this citation in Friedrich Nietzsche’s Human, All Too Human, Part II the other night, mentally noting, “cf. Gaddis”:

188. The Muses as Liars. —“We know how to tell many lies,” so sang the Muses once, when they revealed themselves to Hesiod.—The conception of the artist as deceiver, once grasped, leads to important discoveries.

- The Recognitions: crammed with poseurs and fakers, forgers and con-men, artists and would-be artists.

-

To recognize: To see and know again. Recognition entails time, experience, certitude, authenticity.

-

Who would not dogear or underline or highlight this passage?:

That romantic disease, originality, all around we see originality of incompetent idiots, they could draw nothing, paint nothing, just so the mess they make is original . . .

-

In many ways The Recognitions, or rather the characters in The Recognitions whom we might identify with genuine talent, genius, or spirit (to be clear, I’m thinking of Wyatt/Stephan, Basil Valentine, Stanley, Anselm, maybe, and Frank Sinisterra) are conservative, reactionary even; this is somewhat ironic considering Gaddis’s estimable literary innovations.

-

Esme: A focus for the novel’s masculine gaze, or a critique of such gazes?

-

The central problem of The Recognitions (perhaps): What confers meaning in a desacralized world?

Late in the novel, in one of its many party scenes, Stanley underlines the problem, working in part from Voltaire’s (in)famous quote that, “If there were no God, it would be necessary to invent him”:

. . . even Voltaire could see that some transcendent judgments is necessary, because nothing is self-sufficient, even art, and when art isn’t an expression of something higher, when it isn’t invested you might even say, it breaks up into fragments that don’t have any meaning . . .

Here we think of Wyatt: Wyatt who rejects the ministry, contemporary art, contemporary society, sanity . . .

- Wyatt’s quest: To find truth, meaning, authenticity in a modern world where the sacred does not, cannot exist, is smothered by commerce, noise, fakery . . .

The Recognitions conveys a range of tones, but I like it best when it focuses its energies on comic irony and dark absurdity to detail the juxtapositions and ironies between meaning and noise, authenticity and forgery.

(I like The Recognitions least when its bile flares up too much in its throat, when its black humor tips over into a screed of despair. A more mature Gaddis handles bitterness far better in JR, I think—but I parenthesize this note, as it seems minor even in a list of minor digressions).

Probably my favorite chapter of the book — after the very first chapter, which I believe can stand on its own — is Chapter V of Part II. This is the chapter where Frank Sinisterra reemerges, setting into motion a failed plan to disseminate his counterfeit money (“the queer,” as his accomplice calls it). We also meet Otto’s father, Mr. Pivner, a truly pathetic figure (in all senses of the word). This chapter probably contains more immediate or apparent action than any other in The Recognitions, which largely relies on implication (or suspended reference).

More on Part II, Chapter V: Here we find a savagely satirical and very funny discussion of Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People, a book that seems to stand as an emblem (one of many in The Recognitions) of the degraded commercial world that Gaddis repeatedly attacks. The entire discussion of Carnegie’s book is priceless — it begins on page 497 of my Penguin edition and unfurls over roughly 10 pages—and the book is alluded to enough in The Recognitions to become a motif.

I’ll quote from page 499 a passage that seems to ironically situate How to Win Friends and Influence People against The Recognitions itself (this is one of the many postmodern moves of the novel):

It was written with reassuring felicity. There were no abstrusely long sentences, no confounding long words, no bewildering metaphors in an obfuscated system such as he feared finding in simply bound books of thoughts and ideas. No dictionary was necessary to understand its message; no reason to know what Kapila saw when he looked heavenward, and of what the Athenians accused Anaxagoras, or to know the secret name Jahveh, or who cleft the Gordian knot, the meaning of 666. There was, finally, very little need to know anything at all, except how to “deal with people.” College, the author implied, meant simply years wasted on Latin verbs and calculus. Vergil, and Harvard, were cited regularly with an uncomfortable, if off-hand, reverence for their unnecessary existences . . . In these pages, he was assured that whatever his work, knowledge of it was infinitely less important that knowing how to “deal with people.” This was what brought a price in the market place; and what else could anyone possibly want?

- I’m not sure if Gaddis is ahead of his time or of his time in the above citation.

The Recognitions though, on the whole, feels more reactionary than does his later novel JR, which is so predictive of our contemporary society as to produce a maddening sense of the uncanny in its reader.

- Even more on Part II, Chapter V (which I seem to be using to alleviate the anxiety of having to account for so many of the book’s threads): Here we find a delineation of (then complication of, then shuffling of) the various father-son pairings and substitutions that will play out in the text. (Namely, the series of displacements between Pivner, Otto, and Sinisterra, with the subtle foreshadowing of Wyatt’s later (failed) father-son/mentor-pupil relationship with Sinisterra).

Is it worth pointing out that the father-son displacements throughout the text are reminiscent of Joyce’s Ulysses, a book that Gaddis pointedly denied as an influence?

Ignorant of Gaddis’s deflections, I wrote the following in my review almost three years ago:

Gaddis shows a heavy debt to James Joyce‘s innovations in Ulysses here (and throughout the book, of course), although it would be a mistake to reduce the novel to a mere aping of that great work. Rather, The Recognitions seems to continue that High Modernist project, and, arguably, connect it to the (post)modern work of Pynchon, DeLillo, and David Foster Wallace. (In it’s heavy erudition, numerous allusions, and complex voices, the novel readily recalls both W.G. Sebald and Roberto Bolaño as far as I’m concerned).

- But, hey, Cynthia Ozick found Joyce’s mark on The Recognitions as well (from her 1985 New York Times review of Carpenter’s Gothic):

When ”The Recognitions” arrived on the scene, it was already too late for those large acts of literary power ambition used to be good for. Joyce had come and gone. Imperially equipped for masterliness in range, language and ironic penetration, born to wrest out a modernist masterpiece but born untimely, Mr. Gaddis nonetheless took a long draught of Joyce’s advice and responded with surge after surge of virtuoso cunning.

- We are not obligated to listen to Gaddis’s denials of a Joyce influence, of course. When asked in his Paris Review interview if he’d like to clarify anything about his personality and work, he paraphrases his novel:

I’d go back to The Recognitions where Wyatt asks what people want from the man they didn’t get from his work, because presumably that’s where he’s tried to distill this “life and personality and views” you speak of. What’s any artist but the dregs of his work: I gave that line to Wyatt thirty-odd years ago and as far as I’m concerned it’s still valid.

- And so Nietzsche again, again from Human, All Too Human, Part II:

140. Shutting One’s Mouth. —When his book opens its mouth, the author must shut his.

- And if I’m going to quote German aphorists, here’s a Goethe citation (from Maxims and Reflections) that illustrates something of the spirit of The Recognitions:

There is nothing worth thinking but it has been thought before; we must only try to think it again.

- And if I’m going to quote Goethe, I’ll also point out then that Gaddis began The Recognitions as a parody of Goethe’s Faust. Peter William Koenig writes in his excellent and definitive essay “Recognizing Gaddis’ Recognitions” (published in the Winter Volume Contemporary Literature, 1975):

To understand Gaddis’ relationship to his characters, and thus his philosophical motive in writing the novel, we are helped by knowing how Gaddis conceived of it originally. The Recognitions began as a much smaller and less complicated work, passing through a major evolutionary stage during the seven years Gaddis spent writing it. Gaddis says in his notes: “When I started this thing . . . it was to be a good deal shorter, and quite explicitly a parody on the FAUST story, except the artist taking the place of the learned doctor.” Gaddis later explained that Wyatt was to have all talent as Faust had all knowledge, yet not be able to find what was worth doing. This plight-of limitless talent, limited by the age in which it lives-was experienced by an actual painter of the late 1940s, Hans Van Meegeren, on whom Gaddis may have modeled Wyatt. The authorities threw Van Meegeren into jail for forging Dutch Renaissance masterpieces, but like Wyatt, his forgeries seemed so inspired and “authentic” that when he confessed, he was not believed, and had to prove that he had painted them. Like Faust and Wyatt, Van Meegeren seemed to be a man of immense talent, but no genius for finding his own salvation.

The Faust parody remained uppermost in Gaddis’ mind as he traveled from New York to Mexico, Panama and through Central America in 1947, until roughly the time he reached Spain in 1948. Here Gaddis read James Frazer’s The Golden Bough, and the novel entered its second major stage. Frazer’s pioneering anthropological work demonstrates how religions spring from earlier myths, fitting perfectly with Gaddis’ idea of the modern world as a counterfeit-or possibly inspiring it. In any case, Frazer led Gaddis to discover that Goethe’s Faust originally derived from the Clementine Recognitions, a rambling third-century theological tract of unknown authorship, dealing with Clement’s life and search for salvation. Gaddis adapted the title, broadening the conception of his novel to the story of a wandering, at times misguided hero, whose search for salvation would record the multifarious borrowings and counterfeits of modern culture.

- Is Wyatt the hero of The Recognitions? Here’s Basil Valentine (page 247 of my ed.):

. . . that is why people read novels, to identify projections of their own unconscious. The hero has to be fearfully real, to convince them of their own reality, which they rather doubt. A novel without a hero would be distracting in the extreme. They have to know what you think, or good heavens, how can they know that you’re going through some wild conflict, which is after all the duty of a hero.

- If Wyatt is the hero, then what is Otto? Clearly Otto is a comedic double of some kind for Wyatt, a would-be Wyatt, a different kind of failure . . . but is he a hero?

When I first tried The Recognitions I held Otto in special contempt (from that earlier review of mine):

Otto follows Wyatt around like a puppy, writing down whatever he says, absorbing whatever he can from him, and eventually sleeping with his wife. Otto is the worst kind of poseur; he travels to Central America to finish his play only to lend the mediocre (at best) work some authenticity, or at least buzz. He fakes an injury and cultivates a wild appearance he hopes will give him artistic mystique among the Bohemian Greenwich Villagers he hopes to impress. In the fifth chapter, at an art-party, Otto, and the reader, learn quickly that no one cares about his play . . .

But a full reading of The Recognitions shows more to Otto besides the initial anxious shallowness; Gaddis allows him authentic suffering and loss. (Alternately, my late sympathies for Otto may derive from the recognition that I am more of an Otto than a Wyatt . . .).

- The Recognitions is the work of a young man (“I think first it was that towering kind of confidence of being quite young, that one can do anything,” Gaddis says in his Paris Review interview), and often the novel reveals a cockiness, a self-assurance that tips over into didactic essaying or a sharpness toward its subjects that neglects to account for any kind of humanity behind what Gaddis attacks. The Recognitions likes to remind you that its erudition is likely beyond yours, that it’s smarter than you, even as it scathingly satirizes this position.

I think that JR, a more mature work, does a finer job in its critique of contemporary America, or at least in its characterization of contemporary Americans (I find more spirit or authentic humanity in Bast and Gibbs and JR than in Otto or Wyatt or Stanley). This is not meant to be a knock on The Recognitions; I just found JR more balanced and less showy; it seems to me to be the work of an author at the height of his powers, if you’ll forgive the cliché.

I’ll finish this riff-point by quoting Gaddis from The Paris Review again:

Well, I almost think that if I’d gotten the Nobel Prize when The Recognitions was published I wouldn’t have been terribly surprised. I mean that’s the grand intoxication of youth, or what’s a heaven for.

(By the way, Icelandic writer Halldór Kiljan Laxness won the Nobel in lit in 1955 when The Recognitions was published).

- Looking over this riff, I see it’s lengthy, long on outside citations and short on plot summary or recommendations. Because I don’t think I’ve made a direct appeal to readers who may be daunted by the size or reputation or scope of The Recognitions, let me be clear: While this isn’t a book for everyone, anyone who wants to read it can and should. As a kind of shorthand, it fits (“fit” is not the right verb) in that messy space between modernism and postmodernism, post-Joyce and pre-Pynchon, and Gaddis has a style and approach that anticipates David Foster Wallace. (It’s likely that if you made it this far into the riff that you already know this or, even more likely, that you realize that these literary-historical situations mean little or nothing).

26.Very highly recommended.

James Wood, writing about Virginia Woolf in his essay “Virginia Woolf’s Mysticism” (collected in The Broken Estate)–

James Wood, writing about Virginia Woolf in his essay “Virginia Woolf’s Mysticism” (collected in The Broken Estate)–