A few years ago, I reread Donald Barthelme’s collection Sixty Stories and wrote about them on this blog. I enjoyed the project immensely. A recent comment on the last of those Sixty Stories posts asked, or demanded, I suppose (the four-word comment is in the imperative voice) that I Now do Forty Stories. Which I am going to now do, Forty Stories.

40. “January” (first published in The New Yorker, 6 April 1987)

“January” begins as a dialogue between two characters, a mode Barthelme would return to repeatedly throughout his later career. The story is ostensibly a Paris Review style interview with one “Thomas Brecker,” who has authored seven books on religion over his thirty-five year career. The story begins as light satire; our Serious Writer is “renting a small villa” in St. Thomas; the interviewer notes that “a houseboy attended us, bringing cool drinks on a brown plastic tray of the sort found in cafeterias.” The interview quickly takes the shape of a career-spanning reflection, with Brecker sliding into a more melancholy mind frame. By the end of the story, the “interviewer” disappears, leaving us in Brecker’s imagination, where we have likely always been, and it’s hard not to read Barthelme’s autobiographical flourishes beneath Brecker’s mordant quips:

I think about my own death quite a bit, mostly in the way of noticing possible symptoms—a biting in the chest—and wondering, Is this it? It’s a function of being over sixty, and I’m maybe more concerned by how than when. That’s a … I hate to abandon my children. I’d like to live until they’re on their feet. I had them too late, I suppose.

39. “The Baby” (Overnight to Many Distant Cities, 1983)

“The Baby” was composed around the same time as “Chablis” (1983); both stories are love letters of paternal affection for an infant daughter. Again, it’s hard not to see Barthelme’s own biography here. His daughter Katherine was an infant at the time he wrote them. While I don’t think “The Baby” is as strong as “Chablis” is (or, at least as strong in my memory — “Chablis” is the first story in Forty Stories, so we’ll get there, I guess) — while I don’t think “The Baby” is as strong as “Chablis,” it’s still a fun little ditty with an anarchic punchline. It’s also, like barely five short paragraphs–just read it.

38. “Great Days” (Great Days, 1979)

As I revisit my notes for “Great Days,” I realize I should probably read the story again, more slowly, and try to tune more into its voice. Or voices. Are there two voices here, or one? I think there is more of a n actual story story here than I can summarize — not that anyone wants summary of Barthelme — but my takeaway is that this is Barthelme doing Stein doing Cubism doing… In his 2009 biography of Barthelme Hiding Man, Tracy Daugherty wrote that New Yorker fiction editor (and early Barthelme champion) Roger Angell rejected an early version of the story (under the title “Tenebrae”). According to Daugherty’s bio, while Angell recognized the story as a “serious work” and a “new form,” he ultimately thought it was too “private and largely abstract” for publication.

I think this bit is lovely read aloud:

—Purple bursts in my face as if purple staples had been stapled there every which way—

—Hurt by malicious criticisms all very well grounded—

—Oh that clown band. Oh its sweet strains.

—The sky. A rectangle of glister. Behind which, a serene brown. A yellow bar, vertical, in the upper right.

—I love you, Harmonica, quite exceptionally.

—By gum I think you mean it. I think you do.

—It’s Portia Wounding Her Thigh.

—It’s Wolfram Looking at His Wife Whom He Has Imprisoned with the Corpse of Her Lover.

37. “Letters to the Editore” (Guilty Pleasures, 1974)

A lively little gem from Barthelme’s mid-seventies “non-fiction” collection Guilty Pleasures. Its inclusion seems to show an editorial need to pad out Forty Stories with more hits than the old boy had strung together by ’87. Anyway. “Letters to the Editore” is a fantastic send-up of small aesthetic aggressions writ large in the slim pages of little magazines. The ostensible subject is a dust-up surrounding an exhibition of so-called “asterisk” paintings by an American in a European gallery—but the real subject is language itself:

The Editor of Shock Art has hardly to say that the amazing fecundity of the LeDuff-Galerie Z controversy during the past five numbers has enflamed both shores of the Atlantic, at intense length. We did not think anyone would care, but apparently, a harsh spot has been touched. It is a terrible trouble to publish an international art-journal in two languages simultaneously, and the opportunities for dissonance have not been missed.

Barthelme’s comedic control of voices here is what makes this “story” an early (which is to say, late) standout in Forty Stories. It is the “opportunities for dissonance” that our author is most interested in and attuned to.

36. “Construction” (first published in The New Yorker, 21 April 1985)

“Construction” is the non-story of a writer flying out West to complete the “relatively important matter of business which had taken me to Los Angeles, something to do with a contract, a noxious contract, which I signed.” The documents he signs are “reproduced on onionskin, which does not feel happy in the hand.” This is one of two decent verbal flares in “Construction”; the other is an extended episode (as verbal flare-ups go) in which we find our Writer-Hero up against the wall of absurdity:

The flight back from Los Angeles was without event, very calm and smooth in the night. I had a cup of hot chicken noodle soup which the flight attendant was kind enough to prepare for me; I handed her the can of chicken noodle soup and she (I suppose, I don’t know the details) heated it in her microwave oven and then brought me the cup of hot chicken noodle soup which I had handed her in canned form, also a number of drinks which helped make the calm, smooth flight more so. The plane was half empty, there had been a half-hour delay in getting off the ground which I spent marveling at a sentence in a magazine, the sentence reading as follows: “[Name of film] explores the issues of love and sex without ever being chaste.” I marveled over this for the full half-hour we sat on the ground waiting for clearance on my return from Los Angeles, thinking of adequate responses, such as “Well we avoided that at least,” but no response I could conjure up was equal to or could be equal to the original text which I tore out of the magazine and folded and placed, folded, in my jacket pocket for further consideration at some time in the future when I might need a giggle.

Barthelme’s stand-in confesses here to what we’ve always known: He’s a scissors-and-paste man, a night ripper with a good ear, a good eye, but mostly one of us, a guy who needs a good giggle.

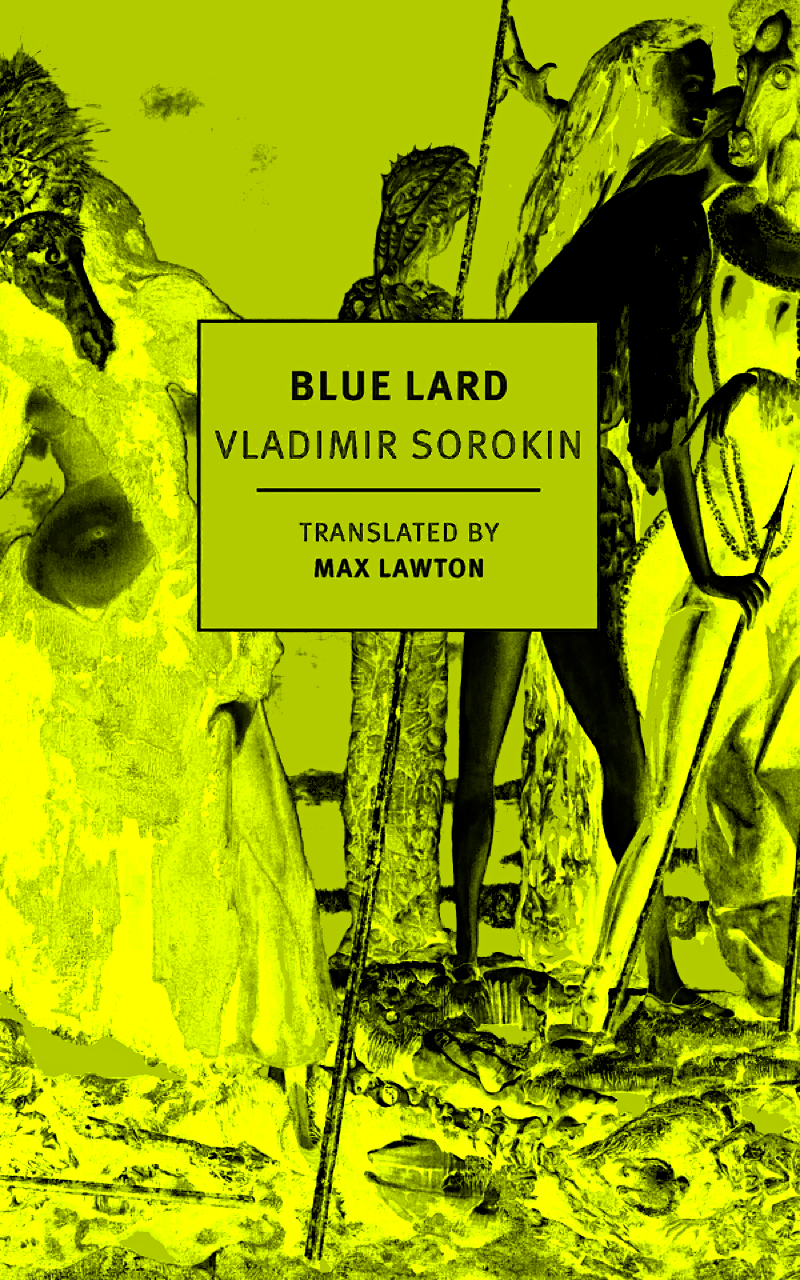

Previously on Blue Lard…

Previously on Blue Lard… Previously on Blue Lard…

Previously on Blue Lard…

Previously on Blue Lard…

Previously on Blue Lard…