In high school I was, like many American intellectual kids, a stranger in a strange land. I made the Berkeley Public Library my refuge, and lived half my life in books. Not only American books—English and French novels and poetry, Russian novels in translation. Transported unexpectedly to college in another strange land, the East Coast, I majored in French lit and went on reading European lit on my own. I felt more at home in some ways in Paris in 1640 or Moscow in 1812 than in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1948.

Much as I loved my studies, their purpose was to make me able to earn a living as a teacher, so I could go on writing. And I worked hard at writing short stories. But here my European orientation was a problem. I wasn’t drawn to the topics and aims of contemporary American realism. I didn’t admire Ernest Hemingway, James Jones, Norman Mailer, or Edna Ferber. I did admire John Steinbeck, but knew I couldn’t write that way. In The New Yorker, I loved Thurber, but skipped over John O’Hara to read the Englishwoman Sylvia Townsend Warner. Most of the people I really wished I could write like were foreign, or dead, or both. Most of what I read drew me to write about Europe; but I knew it was foolhardy to write fiction set in Europe if I’d never been there.

Category: Literature

Gravity’s Rainbow — annotations and illustrations for pages 148-49 | Our history is an aggregate of last moments

—(Quietly) 1 It’s been a prevalent notion 2. Fallen sparks 3. Fragments of vessels broken at the Creation 4. And someday, somehow, before the end, a gathering back to home. A messenger from the Kingdom, arriving at the last moment 5. But I tell you there is no such message, no such home 6—only the millions of last moments… no more. Our history is an aggregate of last moments 7.

From pages 82-83 of Thomas Pynchon’s 1973 novel Gravity’s Rainbow.

1 A stage direction. These are the final lines in a one-act play, a small (cosmically-large) tragicomedy featuring two…nerve cells. Rollo Groast of the White Visitation prefaces a page earlier:

It is part…of an old and clandestine drama for which the human body serves only as a set of very allusive, often cryptic, programme notes—it’s as if the body we can measure is a scrap of this programme found outside in the street, near a magnificent stone theater we cannot enter.

In this little play (its rough setting echoes GR’s own martial satire), a younger cell asks a senior cell if she’s ever been to the “Outer Level” and is somewhat shocked when she tells him that “sooner or later everyone out here has to go Epidermal. No exceptions.”

Is this the first episode of Gravity’s Rainbow staged as a play? I think so.

2 The “prevalent notion” the younger cell subscribes to is characterized in the four sentences that follow, and then rejected in the fifth, the sentence that pivots with “But.” A satire of religious hope, perhaps?—the notion of salvation, redemption, an organizing principle to arrive and tidy all the chaos?

3 The preterite. But also/and—

4 The notations on broken vessels and sparks seem to allude to the Kabbalah of Isaac Luria (1534-1572). I will not attempt a bad paraphrase of Lurianic Kabbalah here, but a basic big picture—sparks—souls, fragments of a one-soul—looking to be rectified. Pynchon, inking heavy his preterite-and-elect theme.

5 The deus ex machina in the last act, the game-winning Hail Mary pass, the Messiah, smiling and terrible…

6 Bummer.

Cf. the opening of Gravity’s Rainbow. From the sixth paragraph:

“You didn’t really believe you’d be saved. Come, we all know who we are by now. No one was ever going to take the trouble to save you, old fellow. . . .”

These are the first lines of dialog in the novel. (If they can be called dialog).

7 The “our” here is biological—one cell to another business—but is there more to human history? Are we more than just our cells? Are there sparks for these vessels?

The narrator here seems to superimpose an answer into the senior cell’s line here: History is simply an imposition, a psychological trick, a way to organize chaos via narrative.

Cf. Pointsman’s lines, which I brought up in some previous annotations:

Will Postwar be nothing but ‘events,’ newly created one moment to the next? No links? Is it the end of history?

This miniature cellular drama comes after the introduction to a minor character in Gravity’s Rainbow I’ve always found intriguing: Gavin Trefoil.

Trefoil, an agent (?!) of The White Visitation, has powers:

Lately, as if all tuned in to the same aethereal Xth Programme, new varieties of freak have been showing up at “The White Visitation,” all hours of the day and night, silent, staring, expecting to be taken care of, carrying machines of black metal and glass gingerbread, off on waxy trances, hyperkinetically waiting only the right trigger-question to start blithering 200 words a minute about their special, terrible endowments. An assault. What are we to make of Gavin Trefoil, for whose gift there’s not even a name yet? (Rollo Groast wants to call it autochromatism.) Gavin, the youngest here, only 17, can somehow metabolize at will one of his amino acids, tyrosine. This will produce melanin, which is the brown-black pigment responsible for human skin color. Gavin can also inhibit this metabolizing by—it appears—varying the level of his blood phenylalanine. So he can change his color from most ghastly albino up through a smooth spectrum to very deep, purplish, black. If he concentrates he can keep this up, at any level, for weeks. Usually he is distracted, or forgets, and gradually drifts back to his rest state, a pale freckled redhead’s complexion.

I suppose I could riff all day on the symbolic/historic implications of Trefoil’s powers: His gradations of color disrupt the binary (black-white, off-on, zero-one) that a Pavlovian like Pointsman insists upon (Trefoil’s super(?!)power falls in line with Roger Mexico’s gradations between 0 and 1).

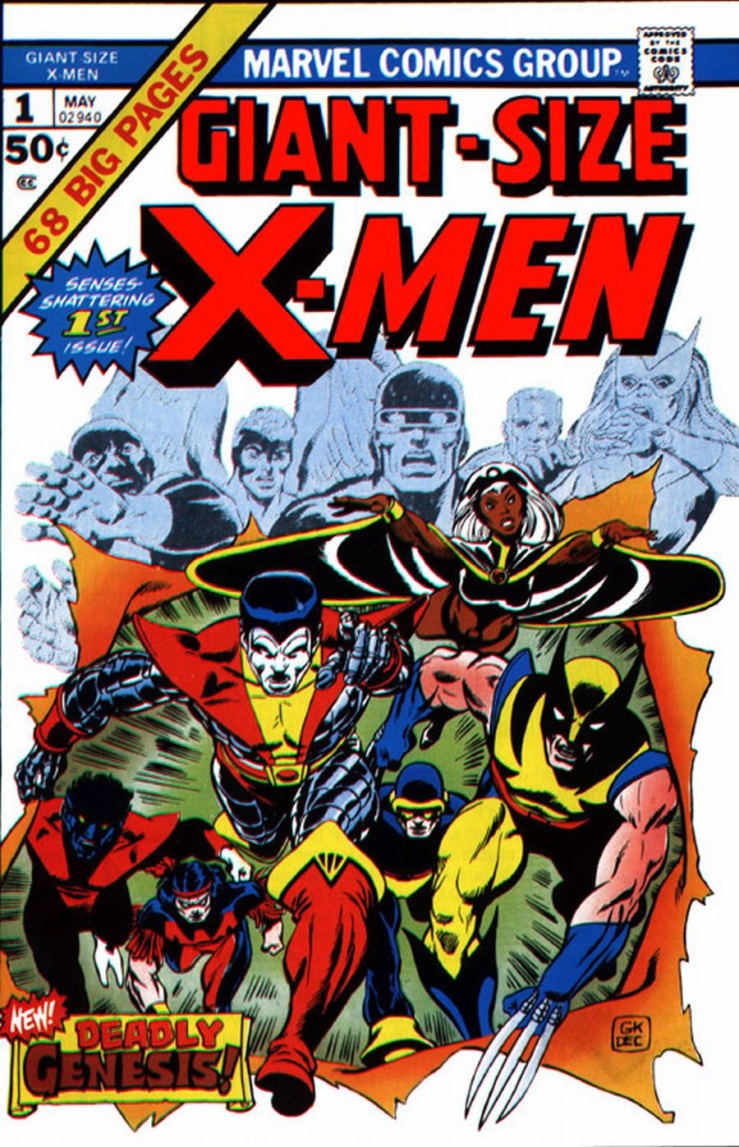

But what really interests me here is Trefoil’s mutant powers and The White Visitation as a sort of potential comic book—I mean what I want to say here is that Pynchon points ahead to the 1975 “reboot” of Uncanny X-Men, and even The New Mutants: Post-global preterite underground weirdos with strange powers. Psychics and witches and protagonists that splinter into nothingness, after going through multiple reboots—(Plechazunga, the Pig-Hero, Rocketman, etc.). (Hell, the Pynchon X-Men team could even have Grigori the Octopus).

The closest X-Men comparison for Gavin Trefoil is probably the shapeshifter baddie X-Men antagonist Mystique, whose powers are obviously more pronounced than Trefoil’s. And there’s also Nightcrawler—maybe my favorite of Chris Claremont’s run on X-Men—or maybe I mean Excalibur. And also blueskinned Beast.

Late in the novel, Our Hero Tyrone Slothrop will help form the superish heroish team the Floundering Four (along with Myrtle Miraculous, zoot-suited Maximillian, and mechanical man Marcel). The Floundering Four will set out to battle the Paternal Peril. (Make of that what you will).

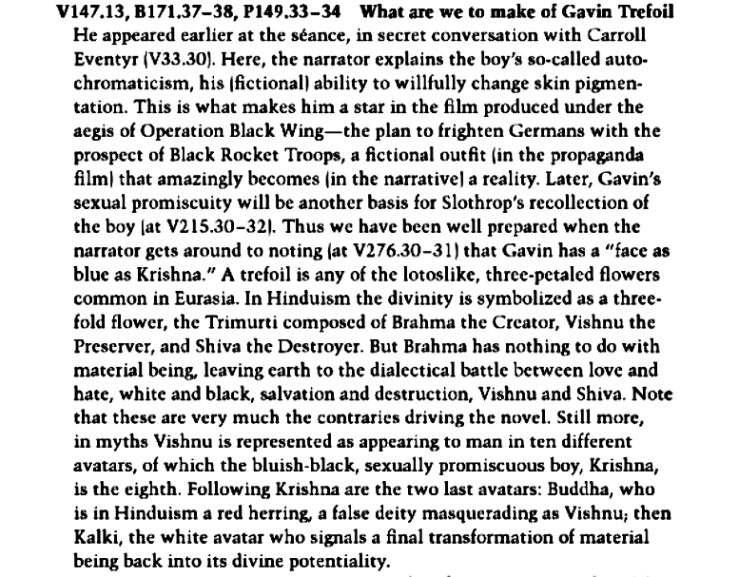

On Trefoil the Blueskin, here’s Steven Weisenburger (A Gravity’s Rainbow Companion):

William Gass and William Gaddis at “The Writer and Religion” conference, 1994 (Audio)

Gravity’s Rainbow — annotations and illustrations for page 105 | The real business of the War is buying and selling

Don’t forget the real business of the War is buying and selling 1. The murdering and the violence are self-policing, and can be entrusted to non-professionals. The mass nature of wartime death is useful in many ways 2. It serves as spectacle, as diversion from the real movements of the War. It provides raw material to be recorded into History, so that children may be taught History as sequences of violence, battle after battle, and be more prepared for the adult world 3. Best of all, mass death’s a stimulus 4 to just ordinary folks, little fellows 5, to try ’n’ grab a piece of that Pie while they’re still here to gobble it up. The true war is a celebration of markets 6. Organic markets, carefully styled “black” 7 by the professionals, spring up everywhere. Scrip, Sterling, Reichsmarks continue to move, severe as classical ballet, inside their antiseptic marble chambers. But out here, down here among the people, the truer currencies come into being. So, Jews are negotiable. Every bit as negotiable as cigarettes, cunt, or Hershey bars. Jews also carry an element of guilt, of future blackmail, which operates, natch, in favor of the professionals. 8

From page 105 of Thomas Pynchon’s 1973 novel Gravity’s Rainbow.

1 Gravity’s Rainbow is often (unjustly and unfairly) maligned as a messy, even pointless affair—but here’s our author speaking through the narrator, offering up one of the novel’s points—clearly, without equivocation.

2 Our narrator digs irony though…

3 Entropy is all—but entropy doesn’t make for good capitalism, by which our sly narrator means, Their Capitalism. The adult world needs to be organized, systematized, caused and effected.

Cf. Jack Gibbs’s rant to his erstwhile young students, early in William Gaddis’s 1975 novel of capitalism, J R:

Before we go any further here, has it ever occurred to any of you that all this is simply one grand misunderstanding? Since you’re not here to learn anything, but to be taught so you can pass these tests, knowledge has to be organized so it can be taught, and it has to be reduced to information so it can be organized do you follow that? In other words this leads you to assume that organization is an inherent property of the knowledge itself, and that disorder and chaos are simply irrelevant forces that threaten it from the outside. In fact it’s the opposite. Order is simply a thin, perilous condition we try to impose on the basic reality of chaos . . .

4 Note the not-so-oblique reference to GR’s theme of stimulus-response (and upending that response).

Not too much earlier in the narrative, dedicated Pavlovian Dr. Edward W.A. Pointsman worries about the end of cause and effect, the rise of entropy:

Will Postwar be nothing but ‘events,’ newly created one moment to the next? No links? Is it the end of history?

5…the preterite?

6 Pynchon reiterates his thesis.

7 Note that organic (entropic?) markets fall outside of Their System—y’know, Them—the Professionals—these organic (chaotic, necessary) markets must be labeled “black” (preterite?).

Here’s another Dutch propaganda poster:

Page 105 of Gravity’s Rainbow “happens,” more or less, in 1944, in the middle of an extended introduction of Katje Borgesius, a Dutch double agent. (Or is that double Dutch agent?). The propaganda poster above strikes me as overtly racist, but also seems to nod to King Kong (1933, dir. Cooper and Schoedsack). Gravity’s Rainbow is larded with references to King Kong, a sympathetic but powerful force of entropy, a force against the Professionals.

From the invaluable annotations at Pynchon Wiki’s Gravity’s Rainbow site (there is no annotation for page 105 at Pynchon Wiki, by the way, and no notes on the passage I’ve cited above either in Steven Weisenburger’s A Gravity’s Rainbow Companion):

King Kong & the Like

Fay Wray look, 57; Fay Wray, 57, 179, 275; “You will have the tallest, darkest leading man in Hollywood,” 179; “headlights burning like the eyes of” 247; “the black scapeape we cast down like Lucifer,” 275; Mitchell Prettyplace book about, 275; “Giant ape” 276; “the Fist of the Ape,” 277; “orangutan on wheels,” 282; taking a shit, 368; “The figures darkened and deformed, resembling apes” 483; “a troupe of performing chimpanzees” 496; “on the tit with no motor skills,” 578; “Negroid apes,” 586; “that sacrificial ape,” 664; “a gigantic black ape,” 688; Carl Denham, 689; poem based on King Kong, 689; See also: actors/directors film/cinema references;

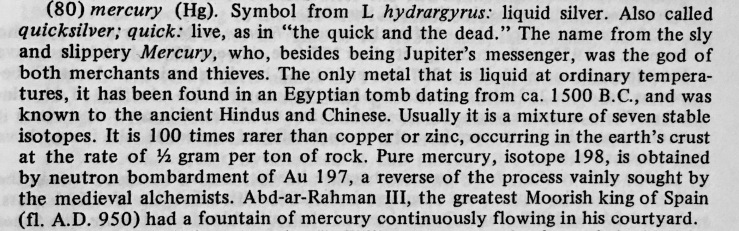

The Kong-figure in the Dutch propaganda poster seems to wear the petasos (winged hat) and wield the caduceus of Hermes or Mercury—god of thieves. But also god of the market, of commerce, merchandise, all things mercenary.

From Joseph T. Shipley’s The Origin of English Words: A Discursive Dictionary of Indo-European Roots (1984):

8 The passage as a whole, which emphasizes war as a conduit for the techne of the market (or do I have that backwards? should I note the market of techne?) echoes an earlier passage. From page 81:

It was widely believed in those days that behind the War—all the death, savagery, and destruction—lay the Führer-principle. But if personalities could be replaced by abstractions of power, if techniques developed by the corporations could be brought to bear, might not nations live rationally? One of the dearest Postwar hopes: that there should be no room for a terrible disease like charisma.

All signs seem to point to No.

Gravity’s Rainbow — Annotations and illustrations for pages 82-83

Overhead, on the molded plaster ceiling, Methodist versions of Christ’s kingdom swarm: lions cuddle with lambs, fruit spills lushly and without pause into the arms and about the feet of gentlemen and ladies, swains and milkmaids. No one’s expression is quite right. The wee creatures leer, the fiercer beasts have a drugged or sedated look, and none of the humans have any eye-contact at all 1 . The ceilings of “The White Visitation” aren’t the only erratic thing about the place, either. It is a classic “folly,” 2 all right. The buttery was designed as an Arabian harem in miniature, for reasons we can only guess at today, full of silks, fretwork and peepholes. One of the libraries served, for a time, as a wallow, the floor dropped three feet and replaced with mud up to the thresholds for giant Gloucestershire Old Spots to frolic, oink, and cool their summers in 3, to stare at the shelves of buckram books and wonder if they’d be good eating 4. Whig eccentricity 5 is carried in this house to most unhealthy extremes. The rooms are triangular, spherical, walled up into mazes 6. Portraits, studies in genetic curiosity, gape and smirk at you from every vantage. The W.C.s contain frescoes of Clive and his elephants stomping the French at Plassy 7, fountains that depict Salome with the head of John (water gushing out ears, nose, and mouth)8, floor mosaics in which are tessellated together different versions of Homo Monstrosus, an interesting preoccupation of the time—cyclops, humanoid giraffe, centaur repeated in all directions 9. Everywhere are archways, grottoes, plaster floral arrangements, walls hung in threadbare velvet or brocade. Balconies give out at unlikely places, overhung with gargoyles whose fangs have fetched not a few newcomers nasty cuts on the head. Even in the worst rains, the monsters only just manage to drool—the rainpipes feeding them are centuries out of repair, running crazed over slates and beneath eaves, past cracked pilasters, dangling Cupids, terra-cotta facing on every floor, along with belvederes, rusticated joints, pseudo-Italian columns, looming minarets, leaning crooked chimneys—from a distance no two observers, no matter how close they stand, see quite the same building 10 in that orgy of self-expression 11, added to by each succeeding owner, until the present War’s requisitioning. Topiary trees line the drive for a distance before giving way to larch and elm: ducks, bottles, snails, angels, and steeplechase riders they dwindle down the metaled road into their fallow silence, into the shadows under the tunnel of sighing trees. The sentry, a dark figure in white webbing, stands port-arms in your 12 masked headlamps, and you 13 must halt for him. The dogs, engineered and lethal, are watching you from the woods. Presently, as evening comes on, a few bitter flakes of snow begin to fall 14.

From pages 82-83 of Thomas Pynchon’s 1973 novel Gravity’s Rainbow.

1 This strikes me as a description of Gravity’s Rainbow.

2 An architectural folly, but another description of Gravity’s Rainbow. (Perhaps ironic. Certainly ironic. Meta-ironic).

3 Late in the novel Our Hero Tyrone Slothrop will take up the mantle of “Plechazunga, the Pig-Hero” — one of many Circean (Odyssean?) transformations.

4 Bibliophagy, baby. Another meta-description of the novel itself.

5 A reference to the Neo-Palladian baroque style that swept Britain in the 18th century?

6 Another description of Gravity’s Rainbow, a self-describing novel…you see where I’m going with this.

7 Clive of India is a very very minor character in Pynchon’s novel Mason & Dixon.

8 See the Solario painting above; you know this old saw of course. The femme fatale, etc. The lines of leakage from ears nose and mouth point to Gravity’s Rainbow’s themes of abjection and dissolution—of unbecoming from the inside out.

9 Another description of Gravity’s Rainbow (disputed). Monster men populated the undiscovered country. Do you know Gaspar Schott?

10 “…no two observers, no matter how close they stand, see quite the same building” — strike building and replace with novel, and we have, perhaps, another meta-description of Gravity’s Rainbow.

11 You know by this point I’m going to say that “orgy of self-expression” is another meta-description of the novel itself, right?

There is, of course, a real orgy (by which I mean non-metaphorical, orgy-orgy) later in Gravity’s Rainbow, on the Anubis.

12 …your? Wha? Whence this narrative shift?

13 You!? And hold on who’s this fellow, this dark figure in white webbing (a sorta kinda oxymoron, maybe)—a sentry sure, a watcher, maybe—a statue? The martial imagery prefigures, perhaps, black and white, Enzian and Tchitcherine, the White Visitation (prefigures? This whole passage is set there!) and the Counterforce…(you’re stretching, dude).

14 Our paragraph begins with “Overhead” and ends with “begin to fall”—the descent of the rocket, the arc of the rainbow, the decline of the human condition. (And curves in other directions too).

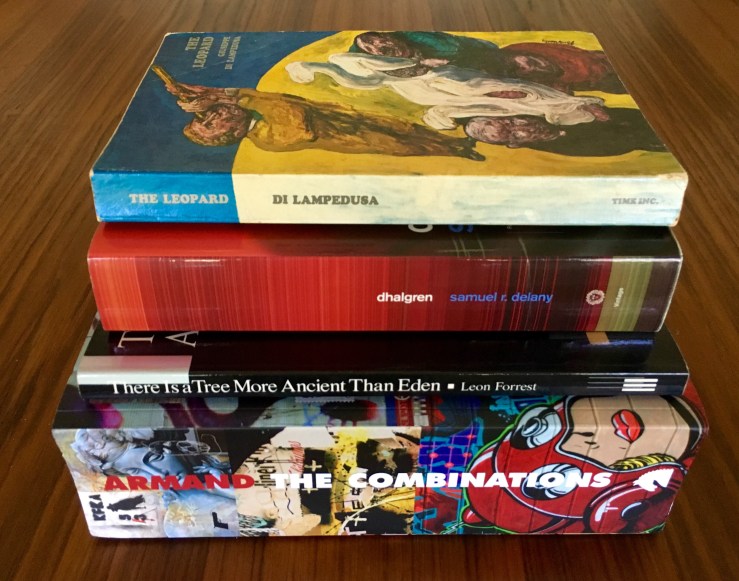

Reading/Have Read/Should Write About

The Leopard, Giusesspe Tomasi di Lampedusa

After a few years of false starts, I finally read Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s 1958 novel The Leopard this August. Then I read it again, immediately (It’s one of only two novels I can recall rereading right away—the other two were Blood Meridian and Gravity’s Rainbow). The Leopard tells the story of Prince Fabrizio of Sicily, who witnesses the end of his era during the Risorgimento, the Italian reunification. Fabrizio is an enchanting character—by turns fiery and lascivious, intellectual and stoic—The Leopard takes us through his mind and through his times. He’s thoroughly complex, unknown even to himself, perhaps. The novel is impossibly rich, sad, electric, a meditation on death, sex, sensuality—pleasure and loss. More mood than plot, The Leopard glides on vibe, its action framed in rich set pieces—fancy balls and sumptuous dinners and games of pleasure in summer estates. But of course there is a plot—several strong plots, indeed (marriage plots and death plots, religious plots and political plots). Yet the narrative’s viewpoint characters keep the plots at bay, or mediate them, rather than propel them forward. Simply one of the better novels I’ve read in years, its final devastating images inked into my memory for as long as I have memory. (English translation by Archibald Colquhoun, by the way).

Dhalgren, Samuel Delany

I think The Leopard initially landed on my radar a few years ago after someone somewhere (where?) described it as a cult novel. Samuel Delany’s Dhalgren (1975) really is a cult novel. I’m about 200 pages into its 800 pages, and I’m ready to abandon the thing. Delany often evokes a fascinating vibe here, conjuring the post-apocalyptic city of Bellona, which is isolated from the rest of America after some unnamed (and perhaps unknown) disaster—there are “scorpions,” gangs who hide in holographic projections of dragons and insects; there is a daily newspaper that comes out dated with a different year each day; there are two moons (maybe). And yet Delany spends more time dwelling on the mundane—I’ve just endured page after page of the novel’s central protagonist, Kid, clearing furniture out of an apartment. I’m not kidding—a sizable chunk of the novel’s third chapter deals with moving furniture. (Perhaps Delany’s nodding obliquely to Poe here?). Dhalgren strives toward metafiction, with the Kid’s attempts to become a poet, but his poetry is so bad, and Delany’s prose is, well, often very, very bad too. Like embarrassingly bad in that early seventies hippy dippy way. If ever a novel were screaming to have every third or second sentence cut, it’s Dhalgren. I’m not sure how much longer I can hold out.

There Is a Tree More Ancient Than Eden, Leon Forrest

I had never heard of Forrest until a Twitter pal corrected that. I started Tree (1973) this weekend; its first chapter “The Lives” is a rush of time, memory, color, texture…religion and violence, history, blood…I’m not sure what’s happening and I don’t care (like Faulkner, it is—I mean, each sentence makes me want to go to the next sentence, into the big weird tangle of it all). Maybe let Ralph Ellison describe it. From his foreword:

As I began to get my bearings in the reeling world of There Is a Tree More Ancient Than Eden, I thought, What a tortured, history-wracked, anguished, Hound-of-Heaven-pursued, Ham-and-Oedipus-cursed, Blake-visioned, apocalypse-prone projection of the human predicament! Yet, simultaneously, I was thinking, Yes, but how furiously eloquent is this man Forrest’s prose, how zestful his jazz-like invention, his parody, his reference to the classics and commonplaces of literature, folklore, tall-tale and slum-street jive! How admirable the manner in which the great themes of life and literature are revealed in the black-white Americanness of his characters as dramatized in the cathedral-high and cloaca-low limits of his imaginative ranging.

Typing this out, I realize that I’m bound to put away Dhalgren and continue on into Forrest.

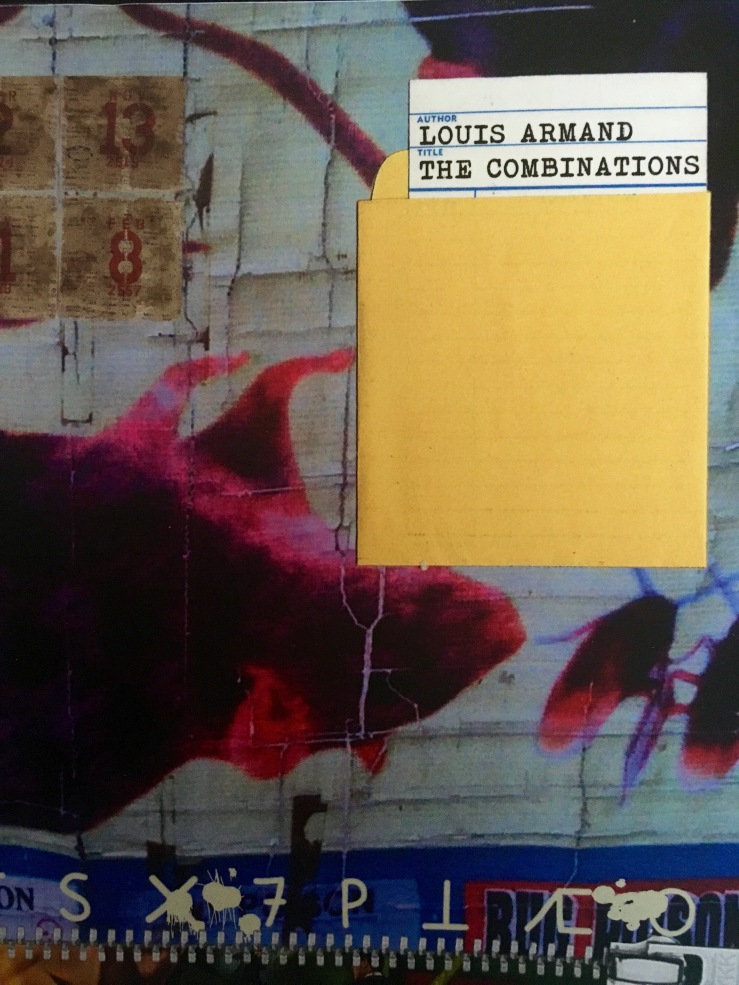

The Combinations, Louis Armand

I read the “Overture” to Armand’s enormous so-called “anti-novel” The Combinations (2016)…the rush of prose reminded me of any number of post-postmodern prose rushers—this isn’t a negative criticism, but I’ll admit a certain wariness with the book’s formal postmodernism—it looks (looks) like Vollmann—discursive, lots of different fonts and forms. I’ll leap in later.

Imagine the long-dead woodman (Nathaniel Hawthorne’s journal entry for September 7th, 1850)

September 7th.–In a wood, a heap or pile of logs and sticks, that had been cut for firewood, and piled up square, in order to be carted away to the house when convenience served,–or, rather, to be sledded in sleighing time. But the moss had accumulated on them, and leaves falling over them from year to year and decaying, a kind of soil had quite covered them, although the softened outline of the woodpile was perceptible in the green mound. It was perhaps fifty years–perhaps more–since the woodman had cut and piled those logs and sticks, intending them for his winter fires. But he probably needs no fire now. There was something strangely interesting in this simple circumstance. Imagine the long-dead woodman, and his long-dead wife and family, and the old man who was a little child when the wood was cut, coming back from their graves, and trying to make a fire with this mossy fuel.

And that is how I have come to discover that I am not pure (Clarice Lispector)

The Combinations (Insanely long book acquired, 9.01.2016)

Louis Armand’s novel (or anti-novel, or whatever) is new from Equus Press.

It’s bigger than a brick.

Lots of footnotes, end notes, different fonts, maps, images, etc. The “text proper” (whatever that means) refuses to begin—epigraphs, notes, an “Overture,” etc.

Here’s the blurb from Equus:

Fiction. Drama. Art. The “European anti-novel” in all its unrepentant glory is here in THE COMBINATIONS, following in the tradition of Sterne, Rabelais, Cervantes, Joyce, Perec.

In 8 octaves, 64 chapters and 888 pages, Louis Armand’s THE COMBINATIONS is an unprecedented “work of attempted fiction” that combines the beauty & intellectual exertion that is chess with the panorama of futility & chaos that is Prague (a.k.a. “Golem City”), across the 20th-century and before/after. Golem City, the ship of fools boarded by the famed D’s (e.g. John) and K’s (e.g. Edward) of the 16th/17th centuries (who attempted and failed to turn lead into gold), and the infamous H’s (e.g. Adolf, e.g. Reinhard) of the 20th (who attempted and succeeded in turning flesh into soap). Armand’s prose weaves together the City’s thousand-and- one fascinating tales with a deeply personal account of one lost soul set adrift amid the early-90s’ awakening from the nightmare that was the previous half-century of communist Mitteleuropa. THE COMBINATIONS is a text whose 1) erudition dazzles, 2) structure humbles, 3) monotony never bores, 4) humour disarms, 5) relentlessness overwhelms, 6) storytelling captivates, 7) poignancy remains poignant, and 8) style simply never exhausts itself. Your move, Reader.

“Dante and the Lobster,” a short story by Samuel Beckett

“Dante and the Lobster”

by

Samuel Beckett

It was morning and Belacqua was stuck in the first of the canti in the moon. He was so bogged that he could move neither backward nor forward. Blissful Beatrice was there, Dante also, and she explained the spots on the moon to him. She shewed him in the first place where he was at fault, then she put up her own explanation. She had it from God, therefore he could rely on its being accurate in every particular. All he had to do was to follow her step by step. Part one, the refutation, was plain sailing. She made her point clearly, she said what she had to say without fuss or loss of time. But part two, the demonstration, was so dense that Belacqua could not make head or tail of it. The disproof, the reproof, that was patent. But then came the proof, a rapid shorthand of the real facts, and Belacqua was bogged indeed. Bored also, impatient to get on to Piccarda. Still he pored over the enigma, he would not concede himself conquered, he would understand at least the meanings of the words, the order in which they were spoken and the nature of the satisfaction that they conferred on the misinformed poet, so that when they were ended he was refreshed and could raise his heavy head, intending to return thanks and make formal retraction of his old opinion.

He was still running his brain against this impenetrable passage when he heard midday strike. At once he switched his mind off its task. He scooped his fingers under the book and shovelled it back till it lay wholly on his palms. The Divine Comedy face upward on the lectern of his palms. Thus disposed he raised it under his nose and there he slammed it shut. He held it aloft for a time, squinting at it angrily, pressing the boards inwards with the heels of his hands. Then he laid it aside.

He leaned back in his chair to feel his mind subside and the itch of this mean quodlibet die down. Nothing could be done until his mind got better and was still, which gradually it did and was. Then he ventured to consider what he had to do next. There was always something that one had to do next. Three large obligations presented themselves. First lunch, then the lobster, then the Italian lesson. That would do to be going on with. After the Italian lesson he had no very clear idea. No doubt some niggling curriculum had been drawn up by someone for the late afternoon and evening, but he did not know what. In any case it did not matter. What did matter was: one, lunch; two, the lobster; three, the Italian lesson. That was more than enough to be going on with. Continue reading ““Dante and the Lobster,” a short story by Samuel Beckett”

It was September now (Cormac McCarthy’s Suttree)

It was September now, a season of rains. The gray sky above the city washed with darker scud like ink curling in a squid’s wake. The blacks can see the boy’s fire at night and glimpses of his veering silhouette slotted in the high nave, outsized among the arches. All night a ruby glow suffuses the underbridge from his garish chancel lamps. The city’s bridges all betrolled now what with old ventriloquists and young melonfanciers. The smoke from their fires issues up unseen among the soot and dust of the city’s right commerce.

Sometimes in the evening Suttree would bring beers and they’d sit there under the viaduct and drink them. Harrogate with questions of city life.

You ever get so drunk you kissed a nigger?

Suttree looked at him. Harrogate with one eye narrowed on him to tell the truth. I’ve been a whole lot drunker than that, he said.

Worst thing I ever done was to burn down old lady Arwood’s house.”

“You burned down an old lady’s house?

Like to of burnt her down in it. I was put up to it. I wasnt but ten year old.

Not old enough to know what you were doing.

Yeah.–Hell no that’s a lie. I knowed it and done it anyways.

Did it burn completely down?

Plumb to the ground. Left the chimbley standin was all. It burnt for a long time fore she come out.

Did you not know she was in there?

I disremember. I dont know what I was thinkin. She come out and run to the well and drawed a bucket of water and thowed it at the side of the house and then just walked on off towards the road. I never got such a whippin in my life. The old man like to of killed me.

Your daddy?

Yeah. He was alive then. My sister told them deputies when they come out to the house, they come out there to tell her I was in the hospital over them watermelons, she told em I didnt have no daddy was how come I got in trouble. But shit fire I was mean when I did have one. It didnt make no difference.

Were you sorry about it? The old lady’s house I mean.

Sorry I got caught.

Suttree nodded and tilted his beer. It occurred to him that other than the melon caper he’d never heard the city rat tell anything but naked truth.

Another vignette from Cormac McCarthy’s Suttree—a transition scene perhaps, but one that draws Suttree and Harrogate closer, even as it underlines their differences.

In my review of Suttree a few years back, I argued that the novel is a grand synthesis of American literature, brimming with literary allusions. I singled out Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily” as the basis for a later scene with Harrogate, so I can’t help but think of Faulkner’s “Barn Burning” here.

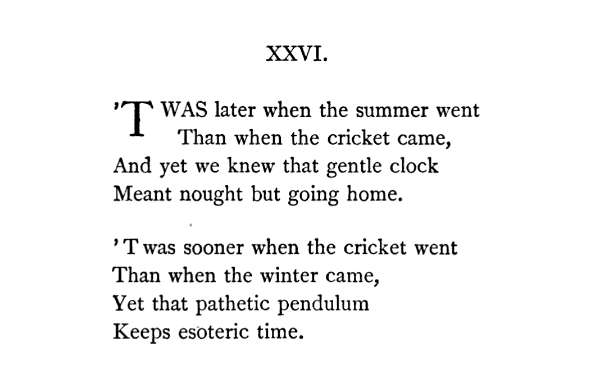

Esoteric time (Emily Dickinson)

All gloom is but a dream and a shadow (Nathaniel Hawthorne’s journal entry for Tuesday, August 30th, 1842)

Tuesday, August 30th.–I was promised, in the midst of Sunday’s rain, that Monday should be fair, and, behold! the sun came back to us, and brought one of the most perfect days ever made since Adam was driven out of Paradise. By the by, was there ever any rain in Paradise? If so, how comfortless must Eve’s bower have been! and what a wretched and rheumatic time must they have had on their bed of wet roses! It makes me shiver to think of it. Well, it seemed as if the world was newly created yesterday morning, and I beheld its birth; for I had risen before the sun was over the hill, and had gone forth to fish. How instantaneously did all dreariness and heaviness of the earth’s spirit flit away before one smile of the beneficent sun! This proves that all gloom is but a dream and a shadow, and that cheerfulness is the real truth. It requires many clouds,long brooding over us, to make us sad, but one gleam of sunshine always suffices to cheer up the landscape. The banks of the river actually laughed when the sunshine fell upon them; and the river itself was alive and cheerful, and, by way of fun and amusement, it had swept away many wreaths of meadow-hay, and old, rotten branches of trees, and all such trumpery. These matters came floating downwards, whirling round and round in the eddies, or hastening onward in the main current; and many of them, before this time, have probably been carried into the Merrimack, and will be borne onward to the sea. The spots where I stood to fish, on my preceding excursion, were now under water; and the tops of many of the bushes, along the river’s margin, barely emerged from the stream. Large spaces of meadow are overflowed.

There was a northwest-wind throughout the day; and as many clouds, the remnants of departed gloom, were scattered about the sky, the breeze was continually blowing them across the sun. For the most part, they were gone again in a moment; but sometimes the shadow remained long enough to make me dread a return of sulky weather. Then would come the burst of sunshine, making me feel as if a rainy day were henceforth an impossibility. . . .

In the afternoon Mr. Emerson called, bringing Mr. —-.

He is a good sort of humdrum parson enough, and well fitted to increase the stock of manuscript sermons, of which there must be a fearful quantity already in the world. Mr. —-, however, is probably one of the best and most useful of his class, because no suspicion of the necessity of his profession, constituted as it now is, to mankind, and of his own usefulness and success in it, has hitherto disturbed him; andtherefore, he labors with faith and confidence, as ministers did a hundred years ago.

After the visitors were gone, I sat at the gallery window, looking down the avenue; and soon there appeared an elderly woman,–a homely, decent old matron, dressed in a dark gown, and with what seemed a manuscript book under her arm. The wind sported with her gown, and blew her veil across her face, and seemed to make game of her, though on a nearer view she looked like a sad old creature, with a pale, thin countenance, and somewhat of a wild and wandering expression. She had a singular gait, reeling, as it were, and yet not quite reeling, from one side of the path to the other; going onward as if it were not much matter whether she went straight or crooked. Such were my observations as she approached through the scattered sunshine and shade of our long avenue, until, reaching the door, she gave a knock, and inquired for the lady of the house. Her manuscript contained a certificate, stating that the old woman was a widow from a foreign land, who had recently lost her son, and was now utterly destitute of friends and kindred, and without means of support. Appended to the certificate there was a list of names of people who had bestowed charity on her, with the amounts of the several donations,–none, as I recollect, higher than twenty-five cents. Here is a strange life, and a character fit for romance and poetry. All the early part of her life, I suppose, and much of her widowhood, were spent in the quiet of a home, with kinsfolk around her, and children, and the lifelong gossiping acquaintances that some women always create about them. But in her decline she has wandered away from all these, and from her native country itself, and is a vagrant, yet with something of the homeliness and decency of aspect belonging to one who has been a wife and mother, and has had a roof of her own above her head,–and, with all this, a wildness proper to her present life. I have a liking for vagrants of all sorts, and never, that I know of, refused my mite to a wandering beggar, when I had anything in my own pocket. There is so much wretchedness in the world, that we may safely take the word of any mortal professing to need our assistance; and, even should we be deceived, still the good to ourselves resulting from a kind act is worth more than the trifle by which we purchase it. It is desirable, I think, that such persons should be permitted to roam through our land of plenty, scattering the seeds of tenderness and charity, as birds of passage bear the seeds of precious plants from land to land, without even dreaming of the office which they perform.

Read Edgar Allan Poe’s satire of transcendentalism, “Never Bet the Devil Your Head”

“Never Bet the Devil Your Head”

by

Edgar Allan Poe

Con tal que las costumbres de un autor,” says Don Thomas de las Torres, in the preface to his “Amatory Poems” “sean puras y castas, importo muy poco que no sean igualmente severas sus obras”- meaning, in plain English, that, provided the morals of an author are pure personally, it signifies nothing what are the morals of his books. We presume that Don Thomas is now in Purgatory for the assertion. It would be a clever thing, too, in the way of poetical justice, to keep him there until his “Amatory Poems” get out of print, or are laid definitely upon the shelf through lack of readers. Every fiction should have a moral; and, what is more to the purpose, the critics have discovered that every fiction has. Philip Melanchthon, some time ago, wrote a commentary upon the “Batrachomyomachia,” and proved that the poet’s object was to excite a distaste for sedition. Pierre la Seine, going a step farther, shows that the intention was to recommend to young men temperance in eating and drinking. Just so, too, Jacobus Hugo has satisfied himself that, by Euenis, Homer meant to insinuate John Calvin; by Antinous, Martin Luther; by the Lotophagi, Protestants in general; and, by the Harpies, the Dutch. Our more modern Scholiasts are equally acute. These fellows demonstrate a hidden meaning in “The Antediluvians,” a parable in Powhatan,” new views in “Cock Robin,” and transcendentalism in “Hop O’ My Thumb.” In short, it has been shown that no man can sit down to write without a very profound design. Thus to authors in general much trouble is spared. A novelist, for example, need have no care of his moral. It is there- that is to say, it is somewhere- and the moral and the critics can take care of themselves. When the proper time arrives, all that the gentleman intended, and all that he did not intend, will be brought to light, in the “Dial,” or the “Down-Easter,” together with all that he ought to have intended, and the rest that he clearly meant to intend:- so that it will all come very straight in the end.

There is no just ground, therefore, for the charge brought against me by certain ignoramuses- that I have never written a moral tale, or, in more precise words, a tale with a moral. They are not the critics predestined to bring me out, and develop my morals:- that is the secret. By and by the “North American Quarterly Humdrum” will make them ashamed of their stupidity. In the meantime, by way of staying execution- by way of mitigating the accusations against me- I offer the sad history appended,- a history about whose obvious moral there can be no question whatever, since he who runs may read it in the large capitals which form the title of the tale. I should have credit for this arrangement- a far wiser one than that of La Fontaine and others, who reserve the impression to be conveyed until the last moment, and thus sneak it in at the fag end of their fables.

Defuncti injuria ne afficiantur was a law of the twelve tables, and De mortuis nil nisi bonum is an excellent injunction- even if the dead in question be nothing but dead small beer. It is not my design, therefore, to vituperate my deceased friend, Toby Dammit. He was a sad dog, it is true, and a dog’s death it was that he died; but he himself was not to blame for his vices. They grew out of a personal defect in his mother. She did her best in the way of flogging him while an infant- for duties to her well- regulated mind were always pleasures, and babies, like tough steaks, or the modern Greek olive trees, are invariably the better for beating- but, poor woman! she had the misfortune to be left-handed, and a child flogged left-handedly had better be left unflogged. The world revolves from right to left. It will not do to whip a baby from left to right. If each blow in the proper direction drives an evil propensity out, it follows that every thump in an opposite one knocks its quota of wickedness in. I was often present at Toby’s chastisements, and, even by the way in which he kicked, I could perceive that he was getting worse and worse every day. At last I saw, through the tears in my eyes, that there was no hope of the villain at all, and one day when he had been cuffed until he grew so black in the face that one might have mistaken him for a little African, and no effect had been produced beyond that of making him wriggle himself into a fit, I could stand it no longer, but went down upon my knees forthwith, and, uplifting my voice, made prophecy of his ruin.

The fact is that his precocity in vice was awful. At five months of age he used to get into such passions that he was unable to articulate. At six months, I caught him gnawing a pack of cards. At seven months he was in the constant habit of catching and kissing the female babies. At eight months he peremptorily refused to put his signature to the Temperance pledge. Thus he went on increasing in iniquity, month after month, until, at the close of the first year, he not only insisted upon wearing moustaches, but had contracted a propensity for cursing and swearing, and for backing his assertions by bets. Continue reading “Read Edgar Allan Poe’s satire of transcendentalism, “Never Bet the Devil Your Head””

“Bartleby” is the first great epic of modern Sloth (Thomas Pynchon)

By the time of “Bartleby the Scrivener: A Story of Wall-Street” (1853), acedia had lost the last of its religious reverberations and was now an offense against the economy. Right in the heart of robber-baron capitalism, the title character develops what proves to be terminal acedia. It is like one of those western tales where the desperado keeps making choices that only herd him closer to the one disagreeable finale. Bartleby just sits there in an office on Wall Street repeating, “I would prefer not to.” While his options go rapidly narrowing, his employer, a man of affairs and substance, is actually brought to question the assumptions of his own life by this miserable scrivener — this writer! — who, though among the lowest of the low in the bilges of capitalism, nevertheless refuses to go on interacting anymore with the daily order, thus bringing up the interesting question: who is more guilty of Sloth, a person who collaborates with the root of all evil, accepting things-as-they-are in return for a paycheck and a hassle-free life, or one who does nothing, finally, but persist in sorrow? “Bartleby” is the first great epic of modern Sloth, presently to be followed by work from the likes of Kafka, Hemingway, Proust, Sartre, Musil and others — take your own favorite list of writers after Melville and you’re bound sooner or later to run into a character bearing a sorrow recognizable as peculiarly of our own time.

From Thomas Pynchon’s 1993 essay “Sloth; Nearer, My Couch, to Thee.”

Endicott, Pyncheon, and others, in scarlet robes, bands, etc. (Nathaniel Hawthorne’s journal entry for August 22nd, 1838)

In the cabinet of the Essex Historical Society, old portraits.–Governor Leverett; a dark mustachioed face, the figure two thirds length, clothed in a sort of frock-coat, buttoned, and a broad sword-belt girded round the waist, and fastened with a large steel buckle; the hilt of the sword steel,–altogether very striking. Sir William Pepperell, in English regimentals, coat, waistcoat, and breeches, all of red broad-cloth, richly gold-embroidered; he holds a general’s truncheon in his right hand, and extends the left towards the batteries erected against Louisbourg, in the country near which he is standing. Endicott, Pyncheon, and others, in scarlet robes, bands, etc. Half a dozen or more family portraits of the Olivers, some in plain dresses, brown, crimson, or claret; others with gorgeous gold-embroidered waistcoats, descending almost to the knees, so as to form the most conspicuous article of dress. Ladies, with lace ruffles, the painting of which, in one of the pictures, cost five guineas. Peter Oliver, who was crazy, used to fight with these family pictures in the old Mansion House; and the face and breast of one lady bear cuts and stabs inflicted by him. Miniatures in oil, with the paint peeling off, of stern, old, yellow faces. Oliver Cromwell, apparently an old picture, half length, or one third, in an oval frame, probably painted for some New England partisan. Some pictures that had been partly obliterated by scrubbing with sand. The dresses, embroidery, laces of the Oliver family are generally better done than the faces. Governor Leverett’s gloves,–the glove part of coarse leather, but round the wrist a deep, three or four inch border of spangles and silver embroidery. Old drinking-glasses, with tall stalks. A black glass bottle, stamped with the name of Philip English, with a broad bottom. The baby-linen, etc., of Governor Bradford of Plymouth County. Old manuscript sermons, some written in short-hand, others in a hand that seems learnt from print.

From Nathaniel Hawthorne’s journal entry for August 22nd, 1837. From Passages from the American Note-Books. In addition to this description, the full journal entry contains a description of a walk, a note on Hawthorne’s ancestors, and no fewer than ten story ideas. The Pyncheons (of whom Thomas Pynchon descended) star in Hawthorne’s underread classic, The House of Seven Gables.

William Faulkner’s short story “Carcassonne”

“Carcassonne”

by

William Faulkner

And me on a buckskin pony with eyes like blue electricity and a mane like tangled fire, galloping up the hill and right off into the high heaven of the world. His skeleton lay still. Perhaps it was thinking about this.

Anyway, after a time it groaned. But it said nothing, which is certainly not like you he thought you are not like yourself, but I can’t say that a little quiet is not pleasant

He lay beneath an unrolled strip of tarred roofing made of paper. All of him that is, save that part which suffered neither insects nor temperature and which galloped unflagging on the destinationless pony, up a piled silver hill of cumulae where no hoof echoed nor left print, toward the blue precipice never gained. This part was neither flesh nor unflesh and he tingled a little pleasantly with its lackful contemplation as he lay beneath the tarred paper bedclothing.

So were the mechanics of sleeping, of denning up for the night, simplified. Each morning the entire bed rolled back into a spool and stood erect in the corner. It was like those glasses, reading glasses which old ladies used to wear, attached to a cord that rolls onto a spindle in a neat case of unmarked gold; a spindle, a case, attached to the deep bosom of the mother of sleep. He lay still, savoring this. Beneath him Rincon followed.

Beyond its fatal, secret, nightly pursuits, where upon the rich and inert darkness of the streets lighted windows and doors lay like oily strokes of broad and overladen brushes. From the docks a ship’s siren unsourced itself. For a moment it was sound, then it compassed silence, atmosphere, bringing upon the eardrums a vacuum in which nothing, not even silence, was. Then it ceased, ebbed; the silence breathed again with a clashing of palm fronds like sand hissing across a sheet of metal.

Still his skeleton lay motionless. Perhaps it was thinking about this and he thought of his tarred paper bed as a pair of spectacles through which he nightly perused the fabric of dreams: Across the twin transparencies of the spectacles the horse still gallops with its tangled welter of tossing flames. Forward and back against the taut roundness of its belly its legs swing, rhythmically reaching and over-reaching, each spurning over-reach punctuated by a flicking limberness of shod hooves. He can see the saddlegirth and the soles of the rider’s feet in the stirrups. The girth cuts the horse in two just back of the withers, yet it still gallops with rhythmic and unflagging fury and without progression, and he thinks of that riderless Norman steed which galloped against the Saracen Emir, who, so keen of eye, so delicate and strong the wrist which swung the blade, severed the galloping beast at a single blow, the several halves thundering on in the sacred dust where him of Bouillon and Tancred too clashed in sullen retreat; thundering on through the assembled foes of our meek Lord, wrapped still in the fury and the pride of the charge, not knowing that it was dead. Continue reading “William Faulkner’s short story “Carcassonne””