PREVIOUSLY:

Introductions + stories 1956-1959

“The Subliminal Man,” Black Friday, and Consumerism

IN THIS RIFF:

“The Greatest Television Show on Earth” (1972)

“My Dream of Flying to Wake Island” (1974)

“The Air Disaster'” (1975)

“Low–Flying Aircraft” (1975)

“The Life and Death of God” (1976)

“Notes Towards a Mental Breakdown” (1976)

“The 60 Minute Zoom” (1976)

“The Smile” (1976)

“The Ultimate City” (1976)

“The Dead Time” (1977)

“The Index” (1977)

“The Intensive Care Unit” (1977)

“Theatre of War” (1977)

“Having a Wonderful Time” (1978)

“One Afternoon at Utah Beach” (1978)

“Zodiac 2000” (1978)

“Motel Architecture” (1978)

1. “Notes Towards a Mental Breakdown” (1976) / “The Index” (1977)

By the end of the sixties, Ballard had found a style and rhetoric to match his weird futurism. His output of stories slowed down considerably in the ’70s, as he found financial comfort and some measure of fame as a writer. If 1969’s collection The Atrocity Exhibition didn’t cement Ballard as a voice at the forefront of avant-garde fiction, then Crash (1973) surely did. Ballard published four novels in the seventies, and as usual, the stories he composed around the same time often feel like sketches or dress rehearsals for bigger ideas.

The two strongest stories here—or maybe, I should just admit, the stories I like best—are “Notes Towards a Mental Breakdown” and “The Index.” Ballard’s repetitions can often be draining, especially if you read all these stories back to back, but “Notes” and “Index” feel vital, necessary—essential. Yes, of course they belong in that ideal collection I’ve been imagining, The Essential Short Stories of J.G. Ballard. Both stories condense Ballard’s obsessions into short, strange, experiments.

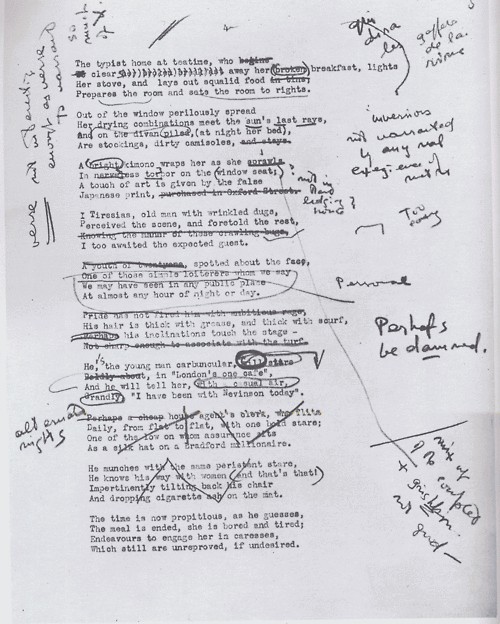

“Notes Towards a Mental Breakdown” reads as a playful but sinister parody of what a fictionalized autobiography of Ballard might look like. The story consists of a single sentence: “A discharged Broadmoor patient compiles ‘Notes Towards a Mental Breakdown,’ recalling his wife’s murder, his trial and exoneration.” Each subsequent paragraph is a numbered footnote, which complicates and disrupts the levels of fictionality and reality that we might expect to inhere in the plot. With its missing mental patients, psycholinguistics, dead, adulterous wife, surrealism, airplanes, etc., “Notes” encapsulates so many of Ballard’s stories to date, yet makes the reader encounter them with fresh perspective. Sample paragraph:

A vital role seems to have been played during these last days by the series of paintings by Max Ernst entitled Garden Airplane Traps, pictures of low walls, like the brick–courses of an uncompleted maze, across which long wings have crashed, from whose joints visceral growths are blossoming. In the last entry of his diary, the day before his wife’s death, 27 March 1975, Loughlin wrote with deceptive calm: ‘Ernst said it all in his comment on these paintings, the model for everything I’ve tried to do… “Voracious gardens in turn devoured by a vegetation which springs from the debris of trapped airplanes… Everything is astonishing, beart–breaking and possible… with my eyes I see the nymph Echo…” Shortly before writing out these lines he had returned to his Hendon apartment to find that his wife had set off for Gatwick Airport with Dr Douglas, intending to catch the 3.15 p.m. flight to Geneva the following day. After calling Richard Northrop, Loughlin drove straight to Elstree Flying Club.

“The Index” (which you can and should read in full here) tells the story of HRH—

Physician and philosopher, man of action and patron of the arts, sometime claimant to the English throne and founder of a new religion, Henry Rhodes Hamilton was evidently the intimate of the greatest men and women of our age. After World War II he founded a new movement of spiritual regeneration, but private scandal and public concern at his growing megalomania, culminating in his proclamation of himself as a new divinity, seem to have led to his downfall.

After a very short introductory note (which I yanked the above from), “The Index” takes the form of “the index to the unpublished and perhaps suppressed autobiography of a man who may well have been one of the most remarkable figures of the twentieth century.” Ballard crams an analysis of the entire 20th century into the index, with bizarre humor and grand results. Forced to read between the lines, HRH (his royal highness) seems to be present at every single meaningful event of the last century, whether he’s advising Churchill:

Churchill, Winston, conversations with HRH, 221; at Chequers with HRH, 235; spinal tap performed by HRH, 247; at Yalta with HRH, 298, ‘iron curtain’ speech, Fulton, Missouri, suggested by HRH, 312; attacks HRH in Commons debate, 367

Ghandhi:

Ghandi, Mahatma, visited in prison by HRH, 251; discussesBhagavadgita with HRH, 253; has dhoti washed by HRH, 254; denounces HRH, 256

–or Hitler:

Hitler, Adolf, invites HRH to Berchtesgaden, 166; divulges Russia invasion plans, 172; impresses HRH, 179; disappoints HRH, 181

I have to share this entry too:

Hemingway, Ernest, first African safari with HRH, 234; at Battle of the Ebro with HRH, 244; introduces HRH to James Joyce, 256; portrays HRH in The Old Man and the Sea, 453

Ballard is at his best when he makes the reader work the hardest (think of “The Beach Murders,” “The Drowned Giant,” or “Why I Want to Fuck Ronald Reagan”), and “The Index” and “Notes” are no exception.

2. “The Greatest Television Show on Earth” (1972) / “The Life and Death of God” (1976)

“The Greatest Television Show on Earth” and “The Life and Death of God” are both composed in a detached, slightly ironic, and highly-omniscient tone that Ballard rarely employs. Most of the time he uses a free indirect style that floats near the harried, paranoid consciousness of one of his (always male) protagonist, constraining the viewpoint to that character. There’s also the occasional first-person voice. It’s worth noting that Ballard’s omniscient voice, usually reserved for wry fables, is one of his strongest (see also: “The Drowned Giant”). This pair of stories—and I do take them as a pair—are thought experiments that ultimately focus on metaphysics, a subject that is somewhat rare in the Ballardverse.

“The Greatest Television Show on Earth” imagines a future (2001!) in which time travel has been perfected and history itself becomes the history channel as billions become addicted to television broadcasts of historical battles. Over time, however, the producers begin to interfere. They try to make history flashier, more violent (sexier?). The story ends with a metaphysical gesture that might be read ironically, although I find it hard to see the conclusion (which I won’t spoil here) as anything other than Ballard’s moralistic reactionary streak alight.

“The Life and Death of God” takes a cue from Voltaire’s quip that if God did not exist it would be necessary to invent him. In this fable/thought experiment, scientists prove beyond doubt (keyword: doubt) that God is real. Ballard imagines a world relieved of radical doubt—a world without faith:

Within two months of the confirmation of the worldwide rumour of God’s existence came the first indications of government concern over the consequences. Industry and agriculture were already affected, though far less than commerce, politics and advertising. Everywhere the results of this new sense of morality, of the virtues of truth and charity, were becoming clear. A legion of overseers, time–keepers and inspectors found themselves no longer needed. Longestablished advertising agencies became bankrupt. Accepting the public demand for total honesty, and fearful of that supreme client up in the sky, the majority of television commercials now ended with an exhortation not to buy their products.

And then things get worse. “The Life and Death” again shows Ballard’s reactionary, elitist stripe, his lack of faith in the so-called common person to make meaning and organize a life without an anchoring center—illusory or otherwise.

3. “The Air Disaster'” (1975) / “Low–Flying Aircraft” (1975) /”The 60 Minute Zoom” (1976) / “The Smile” (1976) / “The Intensive Care Unit” (1977) / “Theatre of War” (1977) / “Having a Wonderful Time” (1978) / “One Afternoon at Utah Beach” (1978) /”Motel Architecture” (1978)

In the order they are listed above, with apologies:

Ballard does cargo cult / Ballard explores child-mutation-as-harbinger-of-new-evolutionary-jump / Ballard does Rear Window (the story anticipates Blue Velvet) / Ballard writes about emotional transference and a sex doll / Ballard mashes up his TV obsessions with his displacement obsessions with his Oedipal obsessions / Ballard imagines a contemporary Civil War in Britain, with American aggressors; there’s a gimmick end here that actually works wonderfully / Ballard’s permanent vacation riff / Ballard writes yet another cheating-wife-leads-to-husband’s-attempt-at-revenge, this time with a Nazi motif / Ballard repeats “Intensive Care Unit,” but mixes it up with voyeurism and a kick of Psycho. (The story anticipates what DeLillo will do a decade later).

Sorry to lump all these together. I probably shouldn’t handle the whole decade of stories at once, but I’m almost finished with this enormous, very long book (dear lord I am ready to be finished) and lumping I shall do. Of this set, “The Intensive Care Unit” and “Theatre of War” are the best, and the most mediocre of the bunch (“Low-Flying Aircraft” and “One Afternoon at Utah Beach”) are better than the mediocre stories of the sixties.

4. “Zodiac 2000” (1978)

Ballard’s most deconstructive, postmodern stories begin with an author’s note, an apologia of sorts, and while I often think these are unnecessary, I’ve also used them to help summarize the stories. So too with “Zodiac 2000”:

An updating, however modest, of the signs of the zodiac seems long overdue. The houses of our psychological sky are no longer tenanted by rams, goats and crabs but by helicopters, cruise missiles and intra–uterine coils, and by all the spectres of the psychiatric ward. A few correspondences are obvious – the clones and the hypodermic syringe conveniently take the place of the twins and the archer. But there remains the problem of all those farmyard animals so important to the Chaldeans. Perhaps our true counterparts of these workaday creatures are the machines which guard and shape our lives in so many ways – above all, the taurean computer, seeding its limitless possibilities. As for the ram, that tireless guardian of the domestic flock, his counterpart in our own homes seems to be the Polaroid camera, shepherding our smallest memories and emotions, our most tender sexual acts. Here, anyway, is an s–f zodiac, which I assume the next real one will be…

If “Zodiac 2000” doesn’t quite work as well as Ballard’s other list-driven/fractured stories, it’s probably because he attempts to screw a plot-driven thriller onto his weird frame. It’s almost as if he has a left-over story that wasn’t quite good enough to sell, and says, hey, I’ve got this idea for a structure, let me mash it all together. In Ballard’s best stuff, frame and content are inseparable; “Zodiac 2000″ is not Ballard’s best” — but it’s still more interesting than his most mediocre.

5. “The Ultimate City” (1976)

Speaking of mediocre: “The Ultimate City” is a very long short story, a novella really, that I invite anyone reading The Complete Short Stories of J.G. Ballard to feel totally okay about skipping. You’ve read this story before, under several different titles, by this point, or maybe you’ll read it later. It’s another thought experiment dressed up as an essay dressed up as an adventure story. At its best there are some good ideas here infused with a heavy dose of environmentalism. At its worst though, “The Ultimate City” is didactic, ponderous, meandering, overstuffed, and redolent of hoary tropes (there’s even a Magical Negro).

6. “The Dead Time” (1977)

1977’s “The Dead Time” is, unless I’m mistaken, Ballard’s first attempt to write directly (if still indirectly) about his experiences as a captive ex-patriot in WWII. Ballard, as is well-known, was interred in a prison camp in Shanghai by the Japanese forces, and this traumatic ordeal undoubtedly underwrites so much of his violent, alienated fiction. If we take Ballard’s childhood internment and the subsequent abject horrors he faced to be the cornerstone of the Ballardverse he would later create, then we must also, significantly, recognize that almost all of Ballard’s fiction up to “The Dead Time” is a displacement and revision of those terrors (which Ballard handled most directly in his mainstream breakthrough, 1984’s Empire of the Sun).

“The Dead Time” focuses on a hero who, released from his Shanghai prison in the final days of WWII, wonders hungry and dissociated through a corpse-and-trash-strewn apocalyptic landscape. He’s charged with the bizarre duty of transporting and then burying a truckload of dead bodies. Little else happens. The tale is, without a doubt, Ballard’s most real, and probably most terrifying story to date:

I tried to pick up another of the corpses, but again my hands froze, and again I felt the same presentiment, an enclosing wall that enveloped us like the wire fence around our camp. I watched the flies swarm across my hands and over the faces of the bodies between my feet, relieved now that I would never again be forced to distinguish between us. I hurled the tarpaulin into the canal, so that the air could play over their faces as we sped along. When the engine of the truck had cooled I refilled the radiator with water from the canal, and set off towards the west.

The narrator’s abject trial continues, and we see in the corpses in his charge the grotesque bits and fragments that have fueled the two previous decades of Ballard’s writing:

Under the cover of darkness – for I would not have dared to commit this act by daylight – I returned to the truck and began to remove the bodies one by one, throwing them down on to the road. Clouds of flies festered around me, as if trying to warn me of the insanity of what I was doing. Exhausted, I pulled the bodies down like damp sacks, ruthlessly avoiding the faces of the nuns and the children, the young amputee and the elderly woman.

As we reach the end of the narrative, our hero remarks,

From this time onwards, during the confused days of my journey to my parents’ camp, I was completely identified with my companions. I no longer attempted to escape them.

It’s difficult not to read here some reconciliation here, as if Ballard is finally ready to write through his formative traumas without the intermediary tropes of science fiction or radical paranoia. What we get here is wonderfully, viscerally real. Fantastic stuff, and clearly part of my ideal Essential collection.

7. On the horizon:

Ballard writes the same story three times in a row! We get one of his best stories, “Answers to a Questionnaire”! And I finish! Yay!