I don’t know what’s wrong with me.

First, I bought an ebook of William T. Vollmann’s really really long new novel The Dying Grass a few weeks ago.

I bought this ebook rather late at night, after rather many drinks, against rather better judgment—or, rather, no judgment. If I can reconstruct my thought process: I think I rationalized paying so much money for an electronic file would like, necessitate a commitment to reading The Dying Grass that I might not feel if it were, say, a review copy, or a copy obtained via store credit at my favorite local book shop. Well I’ve been reading the ebook, putting a little edent in it in little eincrements, but it’s still damn long, and our narrator William the Blind can be awfully opaque at times (not to mention the shifts in narrative).

Anyway, I’ve been reading the ebook, which does, I think (?) a nice job of preserving Vollmann’s occasional indulgence in Whitmanesque free verse (prose) style—but well, I sort of want the physical thing too. So I went by my local bookshop in the hopes of securing a copy (and also pick up some Valentine’s books for my kiddoes). No luck in the new hardback section, so they directed me to Historical Fiction, an area I rarely browsed. No luck for The Dying Grass, but there was a hardback copy of Argall there. All 736 pages of it.

Reader, I acquired it.

Why? I don’t know. I love the faux-Elizabethan prose that Pynchon deployed in Mason & Dixon (and I tolerated Barth’s in The Sot-Weed Factor)—and Vollmann’s has a different flavor that’s intriguing (and difficult). The story, the base story, is the Pocahontas story, which in Vollmann’s telling might go past the Pocahontas myth (more than Malick, more than Disney).

But when oh when am I going to get to the thing?!

I’ll close with a selection from Vollmann’s own review of his novel; the review originally ran in the October 7, 2001 edition of The Los Angeles Times, and was later collected in Expelled from Eden:

“Argall,” whose story emblematizes a personified and of course feminine Virginia, is no better or worse than any of the other “Seven Dreams.” That is why nobody reads “Argall.” No one looks for “Argall.” No one can find “Argall.” Good riddance, say I. To quote from “Argall” itself (the reference is to a fellow who’s searching for Pocahontas’ skeleton), “had the critic found her, what would he have done? Coffined her, borne her back seaward to some brown Virginian marsh crowned by grey and yellow weeds? Locked her into his cabinet of curiosities? All he discovered was a menagerie of human and animal remnants. What power could have swallowed her so thoroughly, but ooze?”

Enough. Holding our noses, let’s try to take this menagerie of remnants on its own terms.

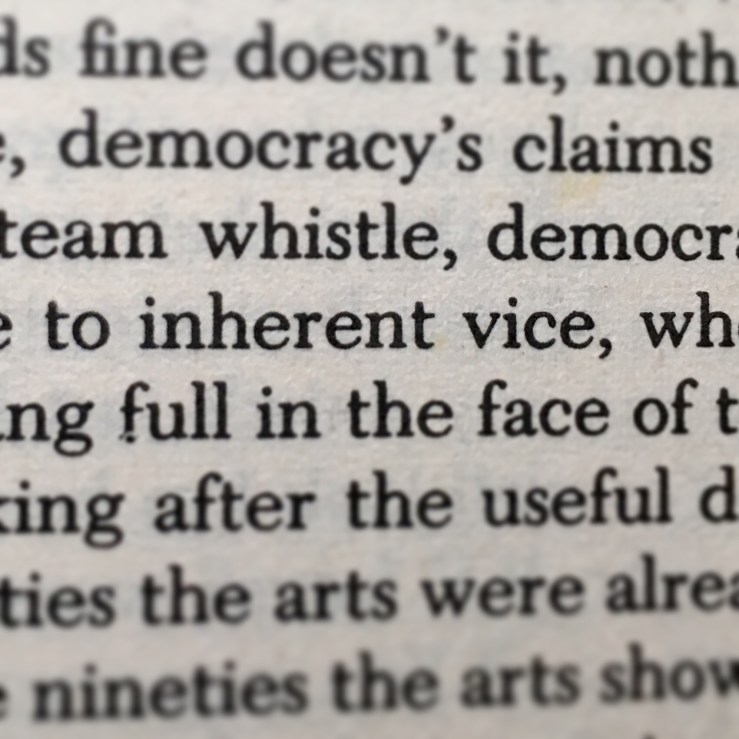

This book’s first sin, as you might have already gathered from the foregoing, consists in its so-called Elizabethan language, whose archaisms, variant spellings and preposterous figures of speech substantially impede the reader in any attempt to envision the ball in any uniform fashion. Here is a sentence plucked at random from the mess: “He search’d for an issue of fair water, there to make another well, for he misdoubted him not that the river they drunk from was somehow tainted with disease, yet could discover no convenient place to make his diggings.” Much time and trouble would have been saved, had this so-called novelist written what he meant: “In order to get more healthful water, he intended to dig a well, but couldn’t.” The arch apostrophe, the ignorant substitution of “drunk” for “drank,” the ink-wasting double negation, well, really all this makes me crave to spew.