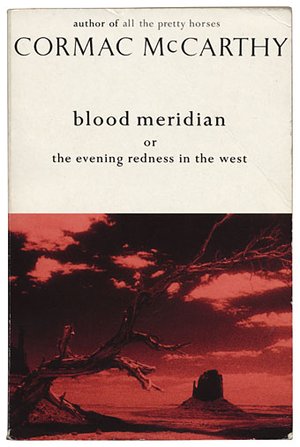

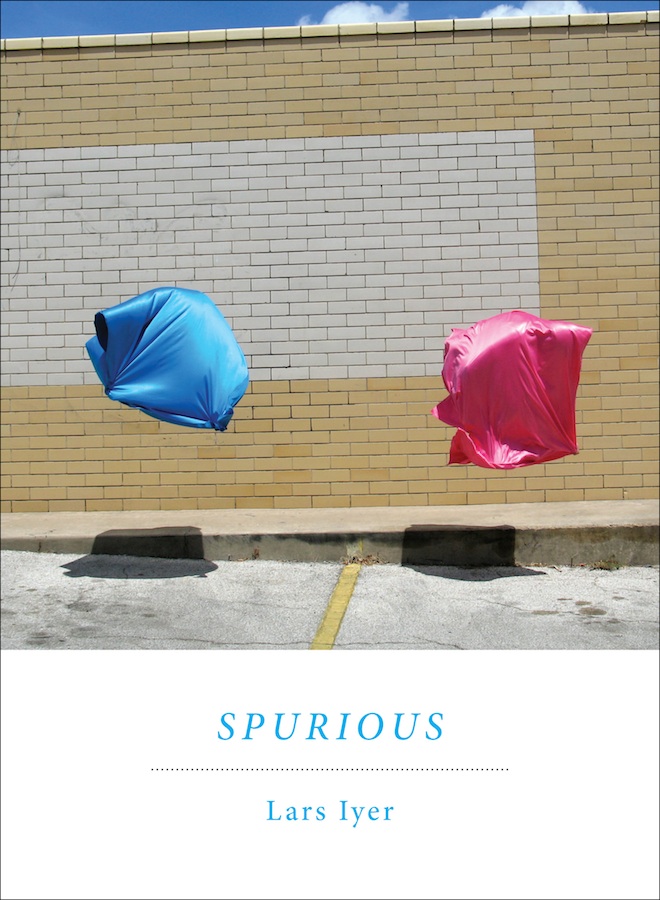

Lars Iyer’s début novel Spurious is about two would-be intellectuals, W., the book’s comic hero, and his closest friend, our narrator Lars. They bitch and moan and despair: it’s the end of the world, it’s the apocalypse; they find themselves incapable of original thought, of producing any good writing. The shadow of Kafka paralyzes them. They travel about Europe, seeking out knowledge and inspiration — or at least a glimpse of some beautiful first editions of Rosenzweig. They attend dreadful academic conferences; they write letters. They flounder and fail. In the meantime, a fungus of seemingly metaphysical proportions infects Lars’s apartment, soaking it through, compounding his desperation, as no one can figure out how to get rid of it—

No one understands the damp. It’s Talmudic. The damp is the enigma at the heart of everything. It draws into it the light of all explanation, all hope. The damp says: I exist, and that is all. I am that I am: so the damp. I will outlast you and outlast everything: so the damp.

The passage is a lovely example of Iyer’s humor, which pervades the book just as the damp creeps through his narrator’s home, absurd and bewildering. Iyer is willing to play with tropes of theology and philosophy in ways that are simultaneously absurd, hyperbolic, and deadly serious. “These are the End Times, but who knows it but us?” his hapless heroes wonder. W. is not without solutions though—-

Every conversation must be driven through the apocalyptic towards the messianic, that’s W.’s principle; the shared sense that it’s all at an end, it’s all finished. He loves nothing better than conversations of this kind, W. says, when everything’s at stake, when everything that could be said is said.

That’s when messianism begins, W. says, You have to wear out speech, to run it down. And then? And then, W. says, inanity begins, reckless inanity. The whole night opens up. You have to drink a great deal to get there. It’s an art.

The dialogue (or monologue pretending to be dialogue, more accurately) highlights the verbal slapstick of Spurious, its willingness to shift direction while retaining tone. “Both characters are mesmerised by a real disaster,” Iyer told me in a recent interview (the interview, by the way, makes a better case for reading Spurious than I can hope to here) . “And both — particularly W. — are mesmerised by their partial responsibility for this disaster. The ‘strained and unreasoning’ laughter of Spurious is a response to the grimness of the world that is of our making.”

W.’s response to our grim, apocalyptic world is a mix of absurd humor and real cruelty toward his friend Lars. And if W. is willing to mock and laugh at his friend, he also mocks and laughs at the world, and himself—only his laughter never absolves or forgives or otherwise deflects the cruelty and grimness of the world (or his own cruelty, in turn). When W. calls Lars fat or chastises his laziness or derides his intellect, there’s a recursive angle to his jabs, a sense that they will return to rest on his own brow. It’s all in good fun except when it’s not.

W. and Lars face the same trial that all thinking people face during the End Times, the inescapable, all-devouring nightmare of history, art, philosophy. Perhaps a passage will explicate better than I—

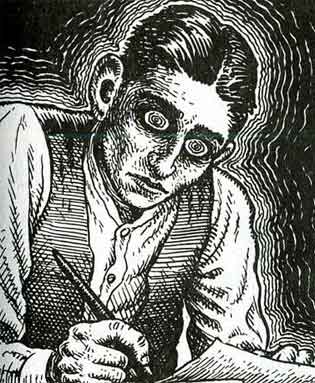

Kafka was always our model, we agree. How is it possible that a human being could write like that?, W. says, again and again. It’s always at the end of the night when he says this, after we’ve drunk a great deal and the sky opens above us, and it is possible to think of what is most important.

At the same time, we have Kafka to blame for everything. Our lives each took a wrong turn when we opened The Castle. It was quite fatal: there was literature itself! We were finished. What could we do, simple apes, but exhaust ourselves in imitation? We had been struck by something we could not understand. It was above us, beyond us, and we were not of its order.

If our heroes are disciples of literature (or the purity of “literature itself”), they are also its prisoners, its slaves, the tormented. W. attempts to find ways out through mathematics and Talmudic theology, but these disciplines entail their own weight and chains—and ultimately, W.’s own shortcomings in these areas only point back to his own reliance on literature (and, in turn, his own shortcomings there again). Still, W. (or Lars, or Iyer, I guess), is willing to share his citations with us, quoting or paraphrasing from a rich intellectual diet.

Although in some ways Spurious is fragmentary and elliptical, a series of riffs, vignettes, and skits, it is also in many ways a traditional novel, with emotionally drawn characters in Lars and W., whose friendship resounds with a deep reality and psychological honesty with which most readers will identify. W. suggests that companionship and friendship are reasons enough to continue existence in the face of despair and absurdity; he then turns around and accuses Lars of being a terrible friend. Iyer offers the kind of truth that has become a cliché, offers it perhaps without cynicism or irony, and then immediately punctures it, even as he reinforces its original truth. Spurious is full of such vacillations, reeling like its often-drunk heroes at times, but always unified by a consistent tone and tight prose. Funny and lively, even when it’s erudite and depressive, Spurious is a lovely little book for drinking and thinking. Read it and pass it on to a dear friend.

Spurious is available now from Melville House; I encourage you again, dear reader, to read my interview with Lars Iyer.