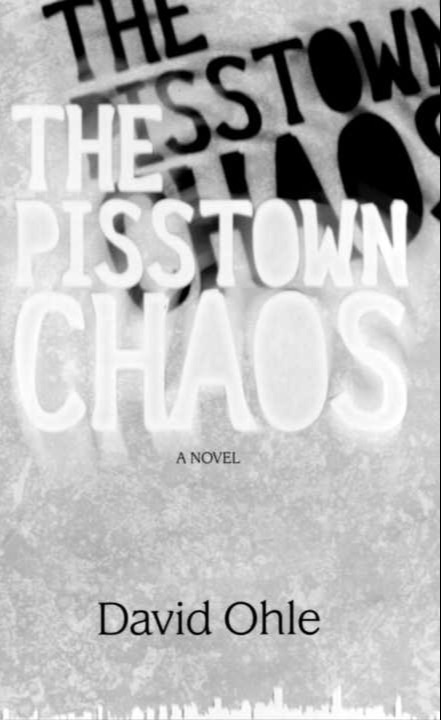

Let’s get the obvious out of the way first: The Pisstown Chaos is an improbably perfect and beautiful name for a novel. If you don’t like the title, The Pisstown Chaos isn’t for you. It is a foul, abject, hilarious, zany vaudeville act, a satire of post-apocalyptic literature, an extended riff on American hucksterism. It’s very funny and will make most readers queasy.

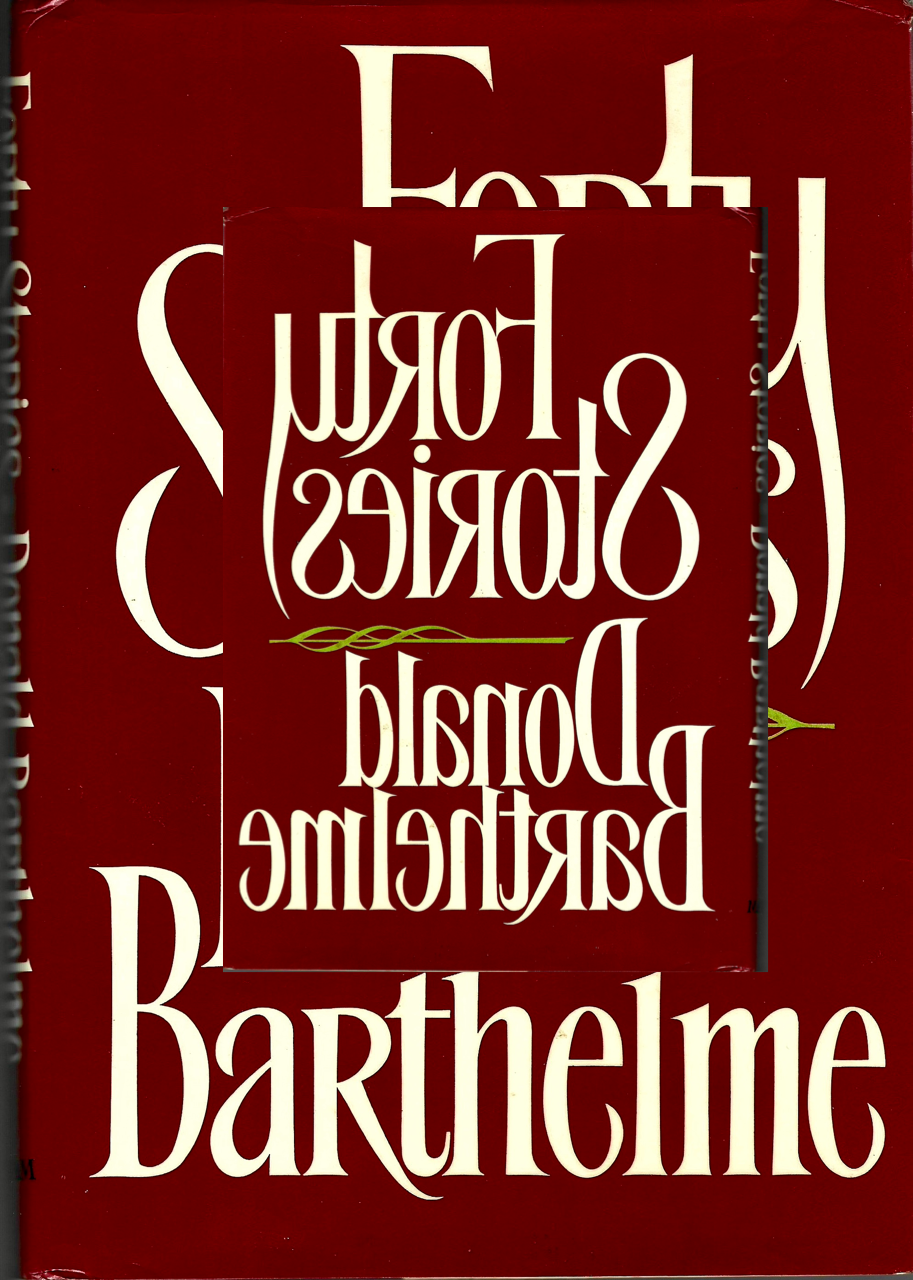

The author of The Pisstown Chaos is David Ohle. The novel was published in 2008; it is the second of three “sequels” to Ohle’s 1972 cult classic Motorman. You do not have to have read Motorman or The Age of Sinatra (2004) to “understand” The Pisstown Chaos. (But you’ll probably want to dig into those if you dig The Pisstown Chaos’s uh pungent urinous ammonia bouquet)

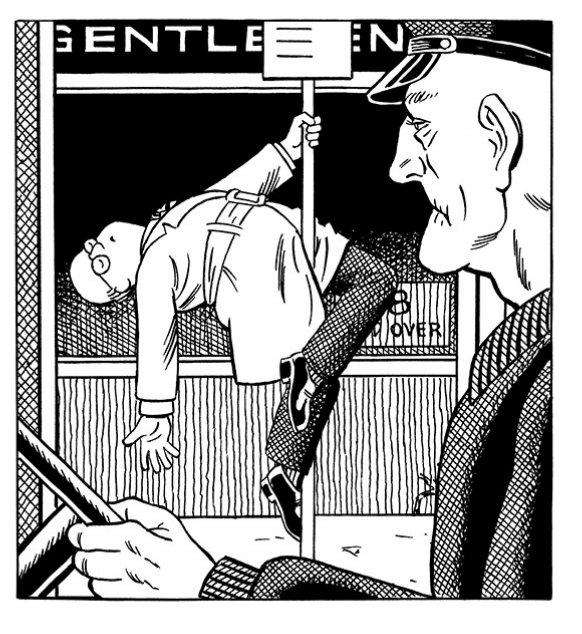

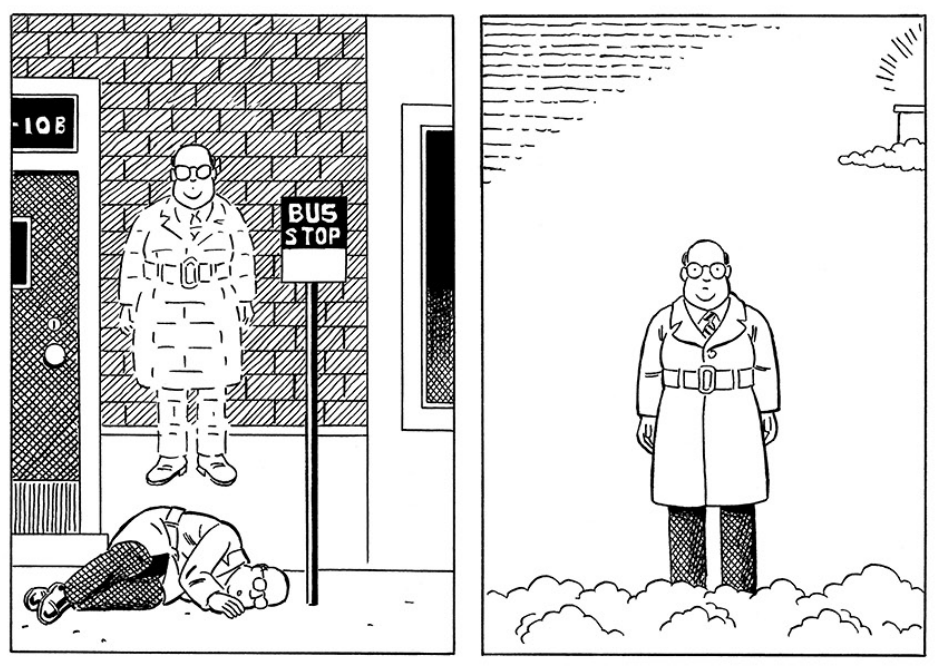

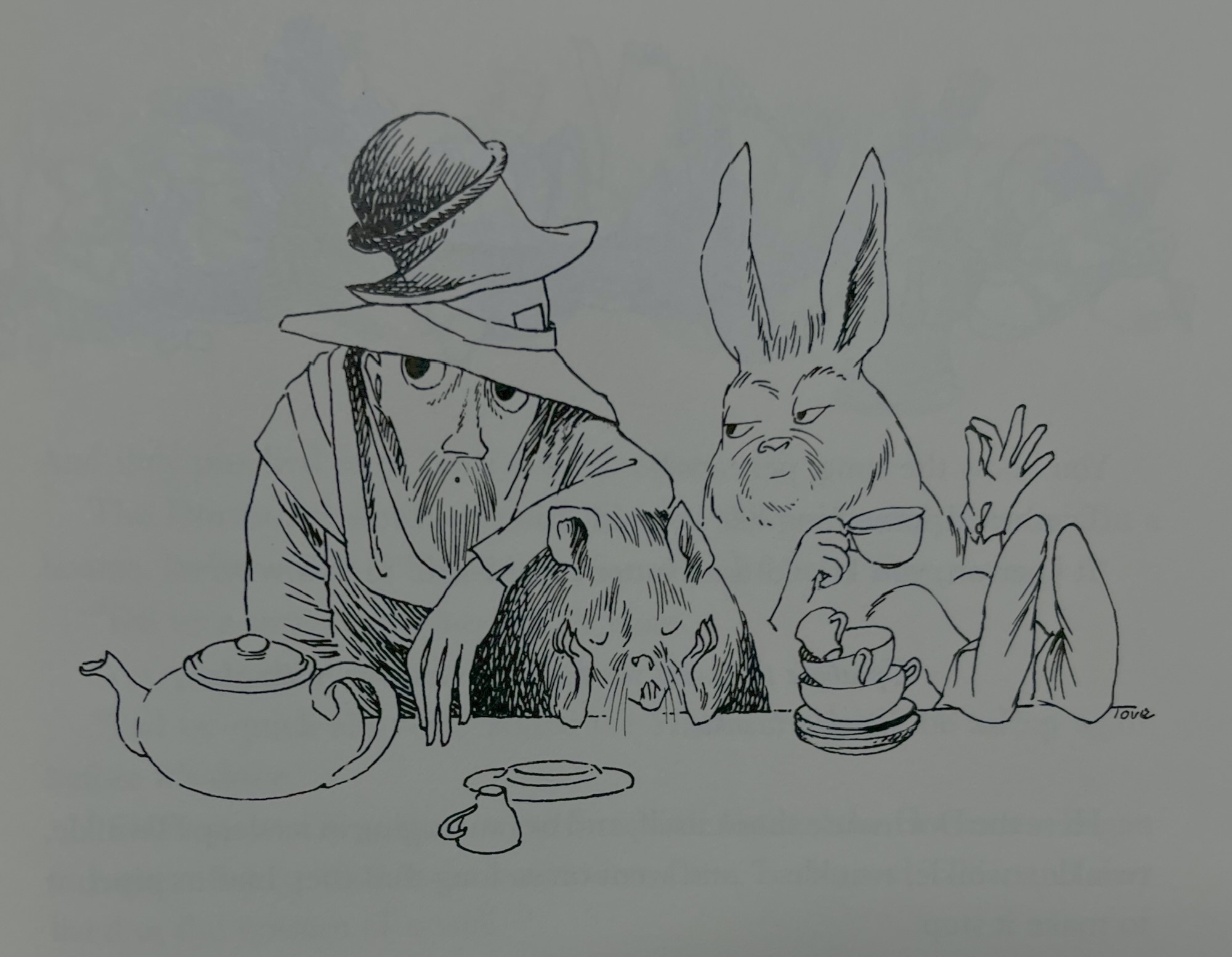

Moldenke, hero of Motorman, is a bit player in The Pisstown Chaos, a walk on, a song-and-dance man with no songs or dances. A storyteller. He’s a zombie, too — a “stinker” in the novel’s parlance — adorned in “black rags and a wide-brimmed white hat,” sporting “an inch-long tube of flesh protruding from just below his ear [which] had the general appearance and shape of an infant’s finger, but lacked a nail. In the end of the tube, a small hole leaked a clear, gelatinous fluid.”

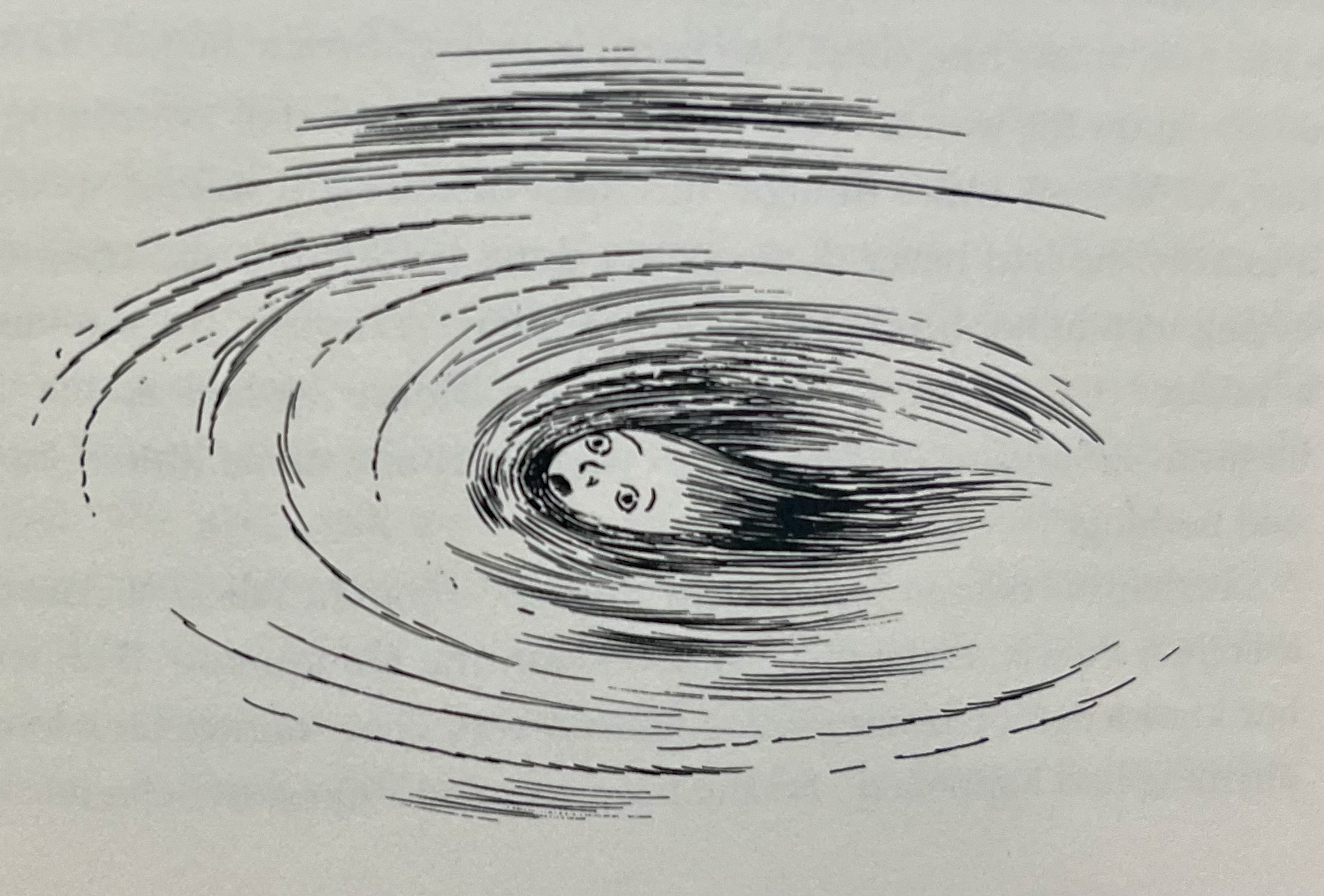

Moldenke, we are to infer, is one of the “Victims of the Pisstown parasite…thought of as dead, but not enough to bury. Gray haggard, poorly dressed, they lay in gutters, sat rigidly on public benches, floated along canals and drank from rain-filled gutters.” He may or may not be centuries old.

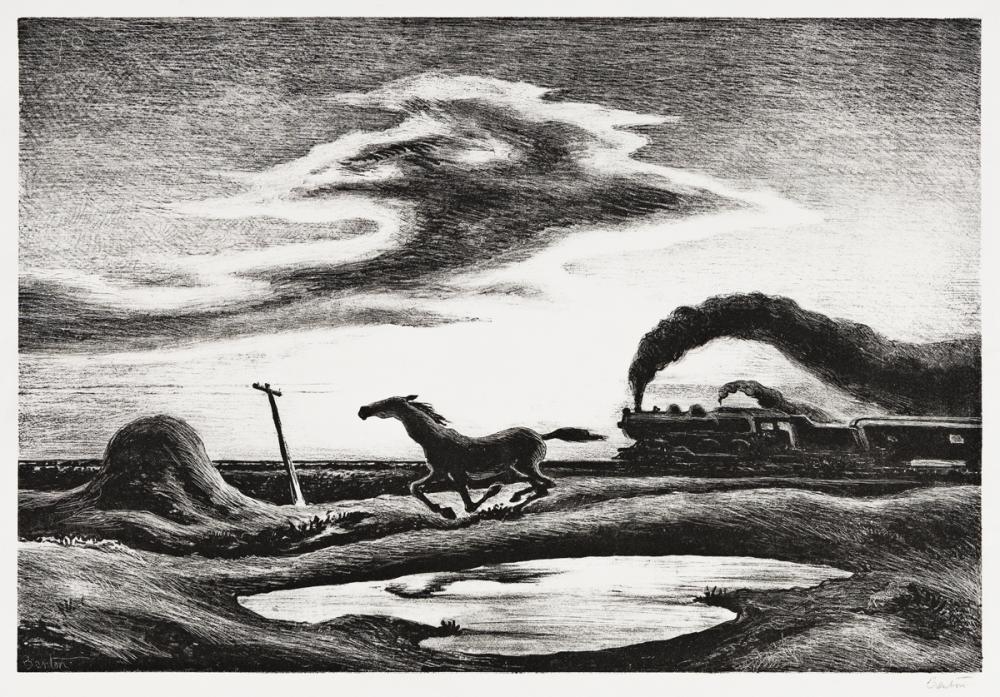

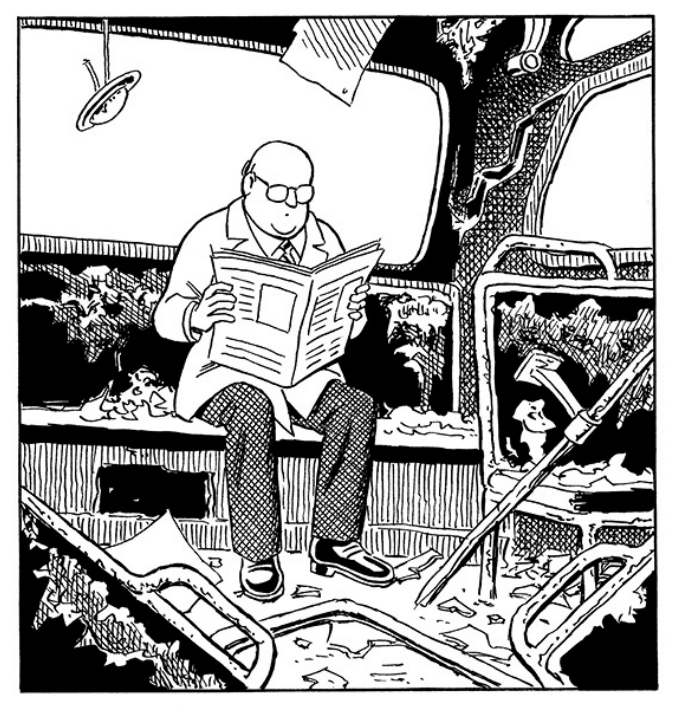

It’s not clear how far into the future we are in the Ohleverse (it doesn’t really matter). After “the Great Forgetting,” and multiple and ongoing Chaoses, the world has regressed, or progressed, or really mutated, into a dusty, wet, gross, nasty post-infrastructure reality. You might read The Pisstown Chaos as a slapstick zombie Western.

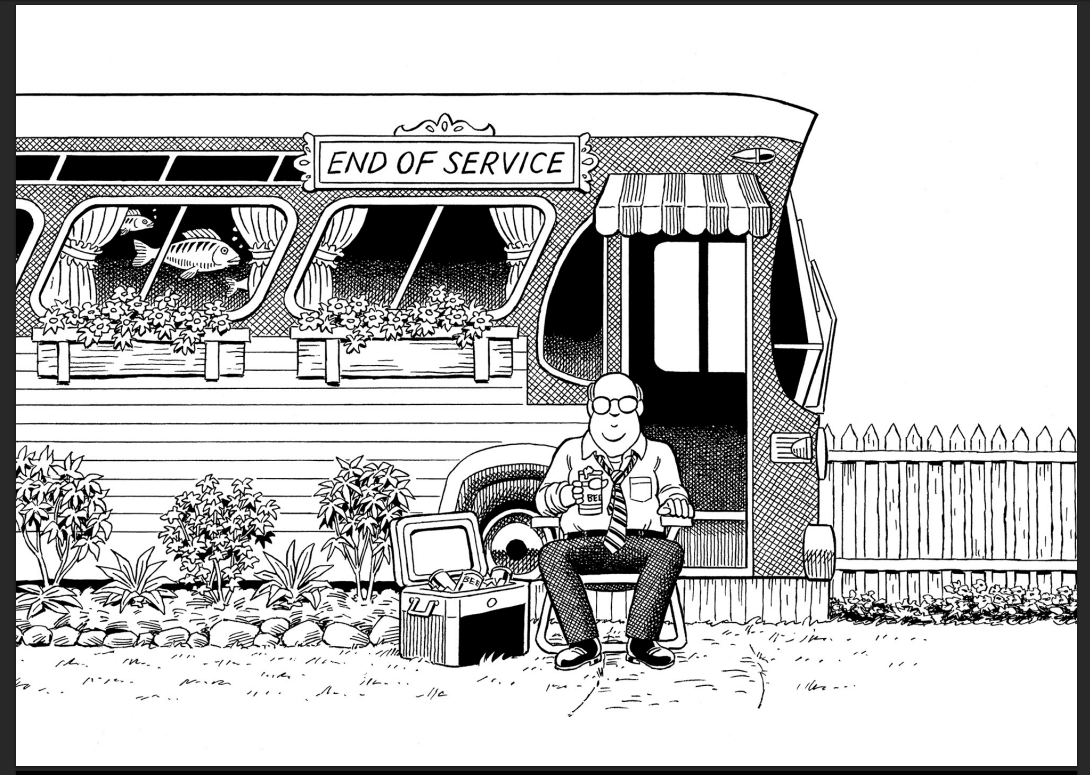

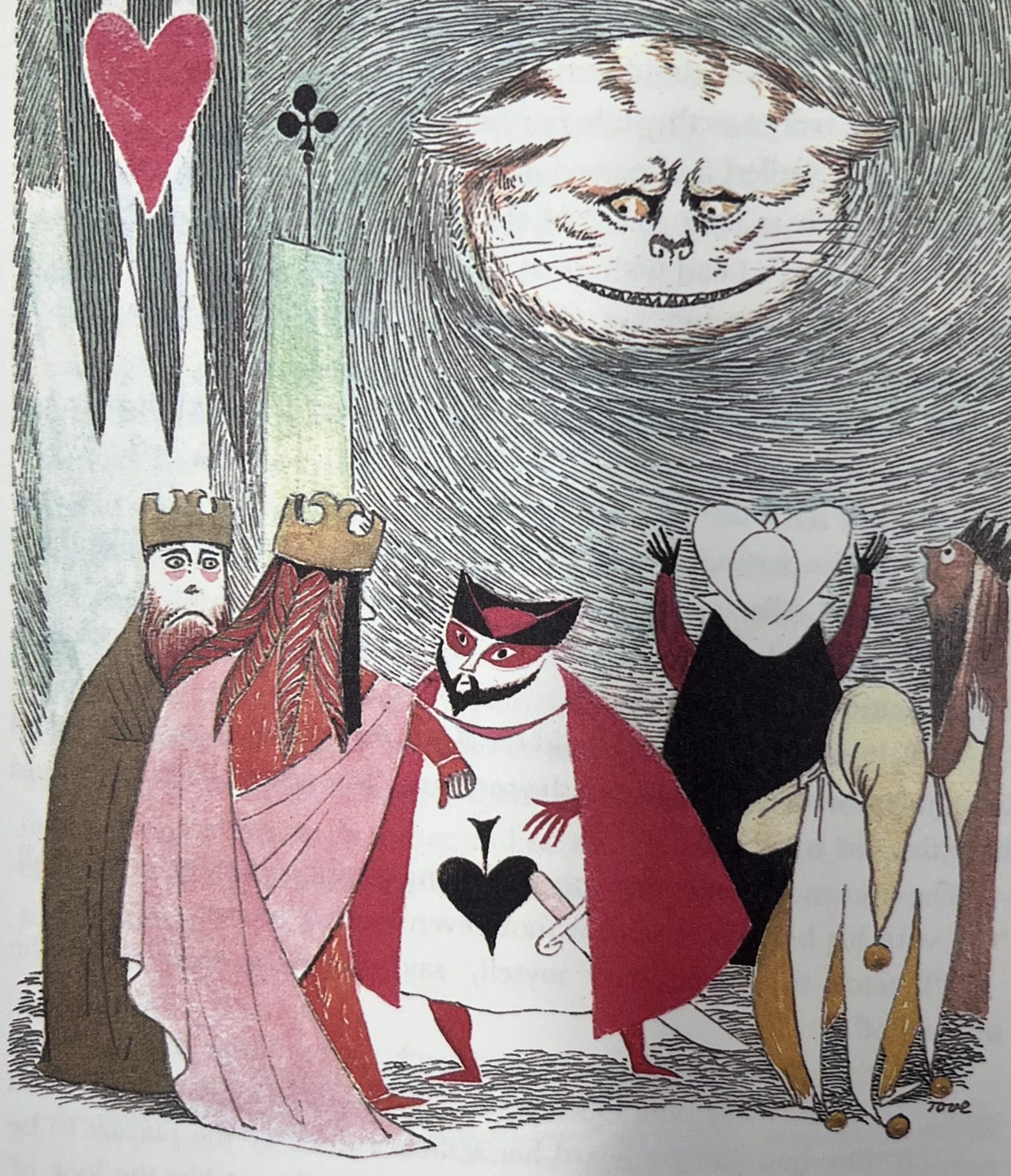

The Reverend Hooker presides over this wonderfully abject world. Hooker’s loose theocratic federation revolves elliptically around a “shifting” scheme. Nothing is permanent, everything is moving, plates spinning on poles. Folks receive their shifting papers and must relocate from, say, a cozy cottage to a prison camp. Or they might end up paired with a new concubine or some such.

That’s the fate of Mildred Balls, née Mildred Vink, who meets Jacob Balls on the road to Witchy Toe. The pair meet cute and get on famously. (And who wouldn’t; after all, suave Jacob Balls was the inventor of the “finely-grained, yellow-tinged powder” known as “Jake” — a kind of post-apocalyptic Bud Light.) Optimistic Jacob is optimistically optimistic of all the shifting, attesting his belief that “in any culture, when boredom and apathy take hold, the currency is debased and the decline is irreversible…What could be more of a tonic than a random redistribution of the populace?” Mildred is less convinced: “The whole scheme is idiotic.”

The Pisstown Chaos focuses on the Balls clan — primarily an older Mildred and her young adult grandkids, Roe and Ophelia. There are stinkers and imps, shifting folk consuming urpflanz, willy, and Jake on their way via Q-ped to Indian Apple or Bum Bay. Reverend Hooker is always lurking in the margins, too, before taking over the narrative’s final pages in a mock apotheosis that brought a stupid smile to my face.

Ohle’s narrative isn’t exactly a picaresque, but it runs on the same energy. Each chapter opens with a series of frank excerpts from the Pisstown rag, the City Moon. Here’s one update of news you need:

A fondness for pickled lips has led to the arrest of a Kootie Fiyo, a stinker known to be a trader in tooth gold and a vicious biter. Fiyo was just leaving the impeteria in South Pisstown when two Guards entered. The proprietor said, “That stink can eat more imp lips than I can heap in front of him. “

The City Moon is not just a source for the goods on a stinker’s glimpse of pickled imps’ lips, but also a gloss on the undead (or un-undead’s) physiology:

What then is a final-stage stinker’s life like? It has been described by scientists as showing a poverty of sensation and a low body temperature. In their nostrils is the persistent odor of urpmilk. The membrane which lines their mouth is extremely tough and is covered with thick scales. They like to touch fur and drink their own urine. Because they have been known to go without food for as long as eighteen years, we can assume that their sense of time passing is also very different from our own.

The Stinker Problem is likely the signature event of whatever century we are in. There’s probably an icky metaphor or allegory somewhere in there, but I find myself disinterested in that end of the novel. But still: Consider Mildred–who wants to find a “cure” for stinkerism–in charge of a crew of stinkers who, after their daily labors, commit “to walking in circles and searching the ground.” But these are not geologists peering into the navel of the world: “‘No, Miss,’ Spanish Johnny said, ‘We like to get dizzy and faint. It’s the way we have fun.'” We’ve all been there.

Mildred’s granddaughter Ophelia commands much of the narrative, shifting about her stations in life. Her domestic comedy with servants Red and Peters is a class-conscious comic delight. Our Miss Madame goes through a series of abject slapstick routines with the Help (including an enema gag that uh, gag me yeah). Here’s a foul episode in the life of Ophelia Balls:

She walked carefully from slippery stone to slippery stone until she got to the potting shed, then blew out the candle. She tried the door and found it locked. Wiping the dirty door-glass, she looked in at Peters, lying on the peat pile with his pants pulled down, fanning his rear with a handful of straw. Red, sitting beside him in Mildred Balls’s underwear, combed Peters’s coarse hair with a tortoise-shell comb. Peters’s cheeks were flushed, his eyes half-closed. When Ophelia entered, the scene seemed all the more lurid for the dim lantern and its flicker.

“I hope you don’t take any offense,” Red said, “but I’ve just mated with Peters here.”

Peters sat up. “I was quietly potting geraniums when that idiot stepped out of a dark corner and made advances, clumsy, lewd advances, with his big willy sticking out. I tried, but I couldn’t resist him.”

“Is that true, Red, that he put up resistance?”

“He lies like a rug. He clearly indicated he wanted me to sex him good and sex him hard.”

Ophelia saw the pointlessness of going any further with the inquiry. “All is forgiven. Let’s move past this.”

“I’ll serve the swan,” Red said.

If I’ll serve the swan isn’t your kinda punchline, The Pisstown Chaos ain’t your cup of Jake. It’s a rich, smelly, gross novel, fun, funny, fueled with 19th-century inventions viewed through piss-colored glasses, aimed at the apocalyptic future. It’s smoked imp-meat served with urpsmoke, a vaudeville buzz against the zombies in the gutter. When I was a kid we held our breath when we passed cemeteries. There are other ceremonies, other totems, but warding off the dead remains a concern.

I have neglected the Balls scion, young Roe, who eventually finds himself attending the Reverend Hooker. Late in the novel, Roe Balls prepares an enema for the theocrat; Hooker then delivers a sermon:

“I’ll warm up the bathroom right away, sir, and get the enema bag ready.”

Once Roe had firmly inserted the hose, the Reverend sat on the pot and closed his eyes. “There, that’s it, Roe. It’s in well enough.”

“Shall I leave you alone now, sir?”

“No. Don’t leave. Let me sermonize a little. I’ll tell you a story, a story with a lesson. In the days when all men were good, they had miraculous power. Lions, mountains, whales, jellyfish, hagfish, birds, rocks, clouds, seas, moved quietly from place to place, just as men ordered them at their whim and fancy. But the human race at last lost its miraculous powers through the laziness of a single man. He was a woodman in the Fertile Crescent. One morning he went into the forest to cut firewood for his master’s hearth. He sawed and split all day, until he had a considerable stack of hickory and oak. Then he stood before the pile and said, ‘Now, march off home!’ The great bundle of wood at once got up and began to walk, and the woodman tramped on behind it. But he was a very lazy man. Now, why shouldn’t I ride instead of galloping along this dusty road, he said to himself, and jumped up on the bundle of wood as it was walking in front of him and sat down on top of it. As soon as he did, the wood refused to go. The woodman got angry and began to strike it fiercely with his axe, all in vain. Still the wood refused to go. And from that time the human race had lost its power.”

“That certainly explains everything I’ve ever wondered about, sir.”

“You may clean me now.”

“Yes, sir.”

The punchlines accumulate after the Rev. Hooker’s fable — young Roe’s deadpan line “That certainly explains everything I’ve ever wondered about, sir” made me laugh aloud when I read it, and the following asswipe line is too much — but I think we have here in the fable a key to the novel. Not the key, but a key.

In the Rev’s woodman’s fable, humans once wielded Promethean power over the world. But that power’s contingent; it exists only when humans move with the world, attentive to its rhythms and limits. When the woodman attempts to ride the wood and make it a convenience instead of walking alongside it, cooperation collapses. S’all she wrote.

Ohle’s chaotic, grotesque world echoes his some-time collaborator William Burroughs’ alien abjection. It will also be comfortingly/nauseatingly familiar (familiar?!) with anyone who digs David Cronenberg’s corporeal horrors. The Pisstown Chronicles will also appeal to weirdos who dig the abject fictions of Vladmir Sorokin, José Donoso, and Antoine Volodine.