Saturday, August 13th.–My life, at this time, is more like that of a boy, externally, than it has been since I was really a boy. It is usually supposed that the cares of life come with matrimony; but I seem to have cast off all care, and live on with as much easy trust in Providence as Adam could possibly have felt before he had learned that there was a world beyond Paradise. My chief anxiety consists in watching the prosperity of my vegetables, in observing how they are affected by the rain or sunshine, in lamenting the blight of one squash and rejoicing at the luxurious growth of another. It is as if the original relation between man and Nature were restored in my case, and as if I were to look exclusively to her for the support of my Eve and myself,–to trust to her for food and clothing, and all things needful, with the full assurance that she would not fail me. The fight with the world,–the struggle of a man among men,–the agony of the universal effort to wrench the means of living from a host of greedy competitors,–all this seems like a dream to me. My business is merely to live and to enjoy; and whatever is essential to life and enjoyment will come as naturally as the dew from heaven. This is, practically at least, my faith. And so I awake in the morning with a boyish thoughtlessness as to how the outgoings of the day are to be provided for, and its incomings rendered certain. After breakfast, I go forth into my garden, and gather whatever the bountiful Mother has made fit for our present sustenance; and of late days she generally gives me two squashes and a cucumber, and promises me green corn and shell-beans very soon. Then I pass down through our orchard to the river-side, and ramble along its margin in search of flowers. Usually I discern a fragrant white lily, here and there along the shore, growing, with sweet prudishness, beyond the grasp of mortal arm. But it does not escape me so. I know what is its fitting destiny better than the silly flower knows for itself; so I wade in, heedless of wet trousers, and seize the shy lily by its slender stem. Thus I make prize of five or six, which are as many as usually blossom within my reach in a single morning;–some of them partially worm-eaten or blighted, like virgins with an eating sorrow at the heart; others as fair and perfect as Nature’s own idea was, when she first imagined this lovely flower. A perfect pond-lily is the most satisfactory of flowers. Besides these, I gather whatever else of beautiful chances to be growing in the moist soil by the river-side,–an amphibious tribe, yet with more richness and grace than the wild-flowers of the deep and dry woodlands and hedge-rows,–sometimes the white arrow-head, always the blue spires and broad green leaves of the pickerel-flower, which contrast and harmonize so well with the white lilies. For the last two or three days, I have found scattered stalks of the cardinal-flower, the gorgeous scarlet of which it is a joy even to remember. The world is made brighter and sunnier by flowers of such a hue. Even perfume, which otherwise is the soul and spirit of a flower, may be spared when it arrays itself in this scarlet glory. It is a flower of thought and feeling, too; it seems to have its roots deep down in the hearts of those who gaze at it. Other bright flowers sometimes impress me as wanting sentiment; but it is not so with this.

Well, having made up my bunch of flowers, I return home with them. . . . Then I ascend to my study, and generally read, or perchance scribble in this journal, and otherwise suffer Time to loiter onward at his own pleasure, till the dinner-hour. In pleasant days, the chief event of the afternoon, and the happiest one of the day, is our walk. . . . So comes the night; and I look back upon a day spent in what the world would call idleness, and for which I myself can suggest no more appropriate epithet, but which, nevertheless, I cannot feel to have been spent amiss. True, it might be a sin and shame, in such a world as ours, to spend a lifetime in this manner; but for a few summer weeks it is good to live as if this world were heaven. And so it is, and so it shall be, although, in a little while, a flitting shadow of earthly care and toil will mingle itself with our realities.

Category: Literature

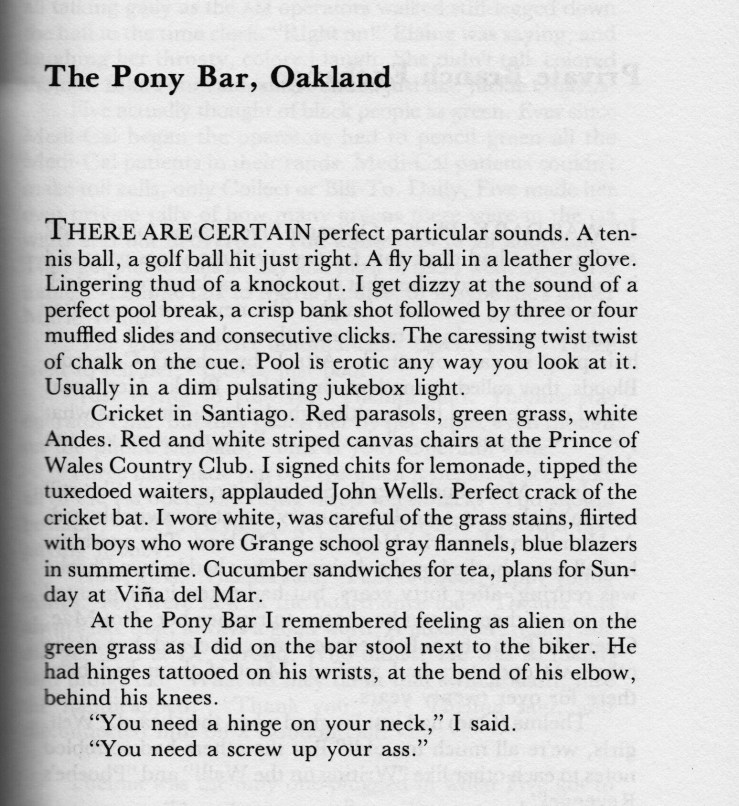

A review of Lucia Berlin’s excellent short story collection, A Manual for Cleaning Women

The 43 stories that comprise Lucia Berlin’s excellent collection A Manual for Cleaning Women braid together to reveal a rich, dirty, sad, joyous world—a world of emergency rooms and laundromats, fancy hotels and detox centers, jails and Catholic schools. Berlin’s stories jaunt through space and time: rough mining towns in Idaho; country clubs and cotillions in Santiago, Chile; heartbreak in New Mexico and New York; weirdness in Oakland and Berkeley; weirdness in Juarez and El Paso.

The center of this world—I’ll call it the Berlinverse, okay?—the center of the Berlinverse is Lucia Berlin herself. “Her life was rich and full of incident, and the material she took from it for her stories was colorful, dramatic and wide-ranging,” writes Lydia Davis in her foreword to Manual. (You can read Davis’s foreword at The New Yorker; it’s a far more convincing case for Berlin than I can manage here). Yes, Berlin’s life was crammed with incident—-so perhaps the strangest moment in A Manual for Cleaning Women is the three-page biography that appends the volume. The bio is strange in how un-strange it is, how it neatly lays out in a few paragraphs the information of Berlin’s life, information we already know as real, as true, from reading the preceding stories. She’s large, she contains multitudes.

Truth is a central theme in these stories. In “Here It Is Saturday,” a version of Berlin teaches fiction writing to prison inmates. She tells them, “you can lie and still tell the truth.” (As I describe the scenario for “Here It Is Saturday” I realize how hokey it sounds—I suppose there are lots of potentially-hokey moments in Berlin’s stories, yet her cruelty and humor deflate them).

In a crucial moment in the late short story “Silence,” the narrator tells us,

I exaggerate a lot and I get fiction and reality mixed up, but I don’t actually ever lie.

The narrator of “Silence” is, of course, a version of Berlin—fictionalized, sure, a persona, yep, an exaggeration, maybe—but she’s utterly believable.

“Silence” is one of many stories that repeat aspects of Berlin’s biography—we get little Lu’s childhood, a father away at the big war, a drunkenly absent mother, a bad drunk grandfather. A Syrian friend betrayed. Nuns. A good drunk uncle. A hit and run. Am I rushing through it? Sorry. To read Berlin is to read this material again and again, in different ways, through different perspectives and filters. “Silence” is particularly interesting to me because it combines material from two earlier stories not collected in Manual: “Stars and Saints” and “The Musical Vanity Boxes,” both published in Black Sparrow Press’s 1990 collection Homesick. These earlier stories are sharper, rawer, and dirtier; the later story—and Berlin’s later stories in general—strike me as more refined. Wiser, perhaps, sussing grace from abject memory.

Berlin’s recollections of the different figures in her life drive these stories, and it’s fascinating to see how key memories erupt into different tales. Berlin’s narrator’s alcoholic grandfather, a famous Texan dentist, sometimes emerges as a sympathetic if grotesque comedic figure, only to appear elsewhere as an abusive monster. Cousin Bella Lynn is a comedic foil in “Sex Appeal,” but an important confidante in “Tiger Bites” (a story of a visit to an abortion provider in Juarez). Several stories center on sister Sally, dying of cancer.

Berlin’s narrator’s four sons (Berlin had four sons) are often in the margins of the stories, but when she mines material from them the results are painful and superb. I note “her sons” in the previous line, but what I really want to note is the friend of one of her sons, a boy she calls Jesse. He shows up in the short “Teenage Punk,” where he’s our narrator’s date to go look at some cranes in a ditch at sunrise. That’s pure Lucia Berlin—weird abject unnatural natural beauty.:

We crossed the log above the slow dark irrigation ditch, over to the clear ditch where we lay on our stomachs, silent as guerrillas. I know, I romanticize everything. It is true though that we lay there freezing for a long time in the fog. It wasn’t fog. Must have been mist from the ditch or maybe just the steam from our mouths.

That brief paragraph showcases much of her technique: Inflation-deflation-resolution-hesitation. The high, low, the in-between. Jesse shows up again in one of the volume’s lengthier (and more painful) tales, “Let Me See You Smile,” a story of police brutality, scandal, and alcoholism.

Most of the stories in Manual are in some way about alcoholism, with the ur-narrator’s mother’s alcoholism haunting the book. In the near-elegy “Panteón de Dolores,” the narrator finds her mother drunk and weeping. When she tries to comfort her mother, she’s rejected; the mother wails, “…the only romance in my life is a midget lamp salesman!” The narrator-daughter reflects, “this sounds funny now, but it wasn’t then when she was sobbing, sobbing, as if her heart would break.” Berlin often punctures her punchlines. In “Mama,” Berlin consoles her dying sister Sally by weaving a fictional ditty about their mother, a paragraph that ends, “She has never before known such happiness.” The story assuages some of her sister’s grief by transmuting it into a realization of love, but the narrator? — “Me…I have no mercy.”

And yet a search for some kind of mercy, some kind of grace propels so many of the stories in A Manual for Cleaning Women. The three-pager “Step,” set in a half-way house, details the residents watching a boxing match between Wilfred Benitez and Sugar Ray Leonard. The recovering (and not-so-recovering) drunks “weren’t asking Benitez to win, just to stay in the fight.” He stays in to the last round before touching his right knee to the canvas. Berlin’s stand-in whispers, “God, please help me.” In “Unmanageable,” the alcoholic narrator finds some measure of grace from others. First from the NyQuil-swilling drunks who share saltine crackers with her in a kind of communion as they wait, shaking, for the liquor store to open at six a.m. And then, from her children. Her oldest son hides her car keys from her.

The same sons are on the narrator’s mind at the end of “Her First Detox,” in which Berlin’s stand-in’s plan for the future takes the form of a shopping list. She’ll cook for her boys when she gets home:

Flour. Milk. Ajax. She only had wine vinegar at home, which, with Antabuse, could throw her into convulsions. She wrote cider vinegar on the list.

Berlin’s various viewpoint characters don’t always do the best job of taking care of themselves, but taking care of other people is nevertheless a preoccupation with the tales in Manual. “Lu” takes care of her dying father in “Phantom Pain”; there’s sick sister Sally; the four sons, of course; a heroin-addicted husband; assorted strays, sure; an old couple in failing health in “Friends”; and the disparate patients who wander in and out of these tales, into doctor’s offices, into emergency rooms, into detox clinics.

And the cleaning women. Caretakers too, of a sort. Laundromats and washing machines are motifs throughout A Manual for Cleaning Women, and it’s no surprise that “Ajax” made the shopping list from “Her First Detox” that I quoted above. An easy point of comparison for Berlin’s writing is the so-called “dirty realism” of Raymond Carver, Denis Johnson, and Carson McCullers. But if Berlin’s realism is dirty, what are we to make of her concern with cleaning, with detox?

As a way of (non-)answering this question, here’s the entirety of the shortest tale in A Manual for Cleaning Women, “Macadam”:

When fresh it looks like caviar, sounds like broken glass, like someone chewing ice.

I’d chew ice when the lemonade was finished, swaying with my grandmother on the porch swing. We gazed down upon the chain gang paving Upson Street. A foreman poured the macadam; the convicts stomped it down with a heavy rhythmic beat. The chains rang; the macadam made the sound of applause.

The three of us said the word often. My mother because she hated where we lived, in squalor, and at least now we would have a macadam street. My grandmother just so wanted things clean — it would hold down the dust. Red Texan dust that blew in with gray tailings from the smelter, sifting into dunes on the polished hall floor, onto her mahogany table.

I used to say macadam out loud, to myself, because it sounded like the name for a friend.

There’s so much in those four paragraphs. Berlin collapses geography and genealogy into ten sentences: daughter, mother, grandmother. Texas, “squalor,” convicts. A road—a new road. Berlin’s narrator converts crushed stone into caviar, then the ice left over after sweet lemonade—and then into the magic of a friend. There’s a lot of beauty in dirt.

I could go on and on about A Manual for Cleaning Women—about how its loose, sharp tales are far more precise than their jagged edges suggest, about its warmth, its depth, its shocking humor, its sadness, its insight. But all I really mean to say is: It’s great, it’s real, it’s true—read it.

A Manual for Cleaning Women is new in trade paperback from Picador. You can read the first story in the collection, “Angel’s Laundromat,” at Picador’s website.

“The Pony Bar, Oakland” — Lucia Berlin

A garden for the blind (From Lampedusa’s The Leopard)

With a wildly excited Bendicò bounding ahead of him he went down the short flight of steps into the garden. Enclosed between three walls and a side of the house, its seclusion gave it the air of a cemetery, accentuated by the parallel little mounds bounding the irrigation canals and looking like the graves of very tall, very thin giants. Plants were growing in thick disorder on the reddish clay, flowers sprouted in all directions, and the myrtle hedges seemed put there to prevent movement rather than guide it. At the end a statue of Flora speckled with yellow-black lichen exhibited her centuries-old charms with an air of resignation; on each side were benches holding quilted cushions, also of gray marble; and in a corner the gold of an acacia tree introduced a sudden note of gaiety. Every sod seemed to, exude a yearning for beauty soon muted by languor.

But the garden, hemmed and almost squashed between these barriers, was exhaling scents that were cloying, fleshy, and slightly putrid, like the aromatic liquids distilled from the relics of certain saints; the carnations superimposed their pungence on the formal fragrance of roses and the oily emanations of magnolias drooping in corners; and somewhere beneath it all was a faint smell of mint mingling with a nursery whiff of acacia and the jammy one of myrtle; from a grove beyond the wall came an erotic waft of early orange blossom.

It was a garden for the blind: a constant offense to the eyes, a pleasure strong if somewhat crude to the nose. The Paul Neyron roses, whose cuttings he had himself bought in Paris, had degenerated; first stimulated and then enfeebled by the strong if languid pull of Sicilian earth, burned by apocalyptic Julies, they had changed into things like flesh-colored cabbages, obscene and distilling a dense, almost indecent, scent which no French horticulturist would have dared hope for. The Prince put one under his nose and seemed to be sniffing the thigh of a dancer from the Opera. Bendicò, to whom it was also proffered, drew back in disgust and hurried off in search of healthier sensations amid dead lizards and manure.

But the heavy scents of the garden brought on a gloomy train of thought for the Prince: “It smells all right here now; but a month ago… ”

He remembered the nausea diffused throughout the entire villa by certain sweetish odors before their cause was traced: the corpse of a young soldier of the Fifth Regiment of Sharpshooters who had been wounded in the skirmish with the rebels at San Lorenzo and come up there to die, all alone, under a lemon tree. They had found him lying face downward in the thick clover, his face covered in blood and vomit, his nails dug into the soil, crawling with ants; a pile of purplish intestines had formed a puddle under his bandoleer. Russo, the agent, had discovered this object, turned it over, covered its face with his red kerchief, thrust the guts back into the gaping stomach with some twigs, and then covered the wound with the blue flaps of the cloak; spitting continuously with disgust, meanwhile, not right on, but very near the body. And all this with meticulous care. “Those swine stink even when they’re dead.” It had been the only epitaph to that derelict death.

After other soldiers, looking bemused, had taken the body away (and yes, dragged it along by the shoulders to the cart so that the puppet’s stuffing fell out again), a De Profundis for the soul of the unknown youth was added to the evening Rosary; and now that the conscience of the ladies in the house seemed placated, the subject was never mentioned again.

The Prince went and scratched a little lichen off the feet of the Flora and then began to stroll up and down; the lowering sun threw an immense shadow of him over the gravelike flower beds.

From Giuseppe di Lampedusa’s 1958 novel The Leopard. English translation by Archibald Colquhoun.

Mr. Thoreau has twice listened to the music of the spheres, which, for our private convenience, we have packed into a musical-box | Nathaniel Hawthorne’s journal entry for August 5th, 1842

Concord, August 5th.–A rainy day,–a rainy day. I am commanded to take pen in hand, and I am therefore banished to the little ten-foot-square apartment misnamed my study; but perhaps the dismalness of the day and the dulness of my solitude will be the prominent characteristics of what I write. And what is there to write about? Happiness has no succession of events, because it is a part of eternity; and we have been living in eternity ever since we came to this old manse. Like Enoch, we seem to have been translated to the other state of being without having passed through death. Our spirits must have flitted away unconsciously, and we can only perceive that we have cast off our mortal part by the more real and earnest life of our souls. Externally, our Paradise has very much the aspect of a pleasant old domicile on earth. This antique house–for it looks antique, though it was created by Providence expressly for our use, and at the precise time when we wanted it–stands behind a noble avenue of balm-of-Gilead trees; and when we chance to observe a passing traveller through the sunshine and the shadow of this long avenue, his figure appears too dim and remote to disturb the sense of blissful seclusion. Few, indeed, are the mortals who venture within our sacred precincts. George Prescott, who has not yet grown earthly enough, I suppose, to be debarred from occasional visits to Paradise, comes daily to bring three pints of milk from some ambrosial cow; occasionally, also, he makes an offering of mortal flowers. Mr. Emerson comes sometimes, and has been feasted on our nectar and ambrosia. Mr. Thoreau has twice listened to the music of the spheres, which, for our private convenience, we have packed into a musical-box. E—- H—- , who is much more at home among spirits than among fleshly bodies, came hither a few times merely to welcome us to the ethereal world; but latterly she has vanished into some other region of infinite space. One rash mortal, on the second Sunday after our arrival, obtruded himself upon us in a gig. There have since been three or four callers, who preposterously think that the courtesies of the lower world are to be responded to by people whose home is in Paradise. I must not forget to mention that the butcher conies twice or thrice a week; and we have so far improved upon the custom of Adam and Eve, that we generally furnish forth our feasts with portions of some delicate calf or lamb, whose unspotted innocence entitles them to the happiness of becoming our sustenance. Would that I were permitted to record the celestial dainties that kind Heaven provided for us on the first day of our arrival! Never, surely, was such food heard of on earth,–at least, not by me. Well, the above-mentioned persons are nearly all that have entered into the hallowed shade of our avenue; except, indeed, a certain sinner who came to bargain for the grass in our orchard, and another who came with a new cistern. For it is one of the drawbacks upon our Eden that it contains no water fit either to drink or to bathe in; so that the showers have become, in good truth, a godsend. I wonder why Providence does not cause a clear, cold fountain to bubble up at our doorstep; methinks it would not be unreasonable to pray for such a favor. At present we are under the ridiculous necessity of sending to the outer world for water. Only imagine Adam trudging out of Paradise with a bucket in each hand, to get water to drink, or for Eve to bathe in! Intolerable! (though our stout handmaiden really fetches our water.) In other respects Providence has treated us pretty tolerably well; but here I shall expect something further to be done. Also, in the way of future favors, a kitten would be very acceptable. Animals (except, perhaps, a pig) seem never out of place, even in the most paradisiacal spheres. And, by the way, a young colt comes up our avenue, now and then, to crop the seldom-trodden herbage; and so does a company of cows, whose sweet breath well repays us for the food which they obtain. There are likewise a few hens, whose quiet cluck is heard pleasantly about the house. A black dog sometimes stands at the farther extremity of the avenue, and looks wistfully hitherward; but when I whistle to him, he puts his tail between his legs, and trots away. Foolish dog! if he had more faith, he should have bones enough.

“Macadam” — Lucia Berlin

“Macadam” by Lucia Berlin

from A Manual for Cleaning Women

When fresh it looks like caviar, sounds like broken glass, like someone chewing ice.

I’d chew ice when the lemonade was finished, swaying with my grandmother on the porch swing. We gazed down upon the chain gang paving Upson Street. A foreman poured the macadam; the convicts stomped it down with a heavy rhythmic beat. The chains rang; the macadam made the sound of applause.

The three of us said the word often. My mother because she hated where we lived, in squalor, and at least now we would have a macadam street. My grandmother just so wanted things clean — it would hold down the dust. Red Texan dust that blew in with gray tailings from the smelter, sifting into dunes on the polished hall floor, onto her mahogany table.

I used to say macadam out loud, to myself, because it sounded like the name for a friend.

As regards literary production, the summer has been unprofitable | Nathaniel Hawthorne’s journal entry for July 28th, 1843

July 28th.–We had green corn for dinner yesterday, and shall have some more to-day, not quite full grown, but sufficiently so to be palatable. There has been no rain, except one moderate shower, for many weeks; and the earth appears to be wasting away in a slow fever. This weather, I think, affects the spirits very unfavorably. There is an irksomeness, a restlessness, a pervading dissatisfaction, together with an absolute incapacity to bend the mind to any serious effort. With me, as regards literary production, the summer has been unprofitable; and I only hope that my forces are recruiting themselves for the autumn and winter. For the future, I shall endeavor to be so diligent nine months of the year that I may allow myself a full and free vacation of the other three.

Nathaniel Hawthorne’s journal entry for July 28th, 1843. From Passages from the American Note-Books.

As a rule, never work for friends (Lucia Berlin)

Linda’s today.

(Cleaning women: As a rule, never work for friends. Sooner or later they resent you because you know so much about them. Or else you’ll no longer like them, because you do.)

But Linda and Bob are good, old friends. I feel their warmth even though they aren’t there. Come and blueberry jelly on the sheets. Racing forms and cigarette butts in the bathroom. Notes from Bob to Linda: “Buy some smokes and take the car . . . dooh-dah doo-dah.” Drawings by Andrea with Love to Mom. Pizza crusts. I clean their coke mirror with Windex.

It is the only place I work that isn’t spotless to begin with. It’s filthy in fact. Every Wednesday I climb the stairs like Sisyphus into their living room where it always looks like they are in the middle of moving.

I don’t make much money with them because I don’t charge by the hour, no carfare. No lunch for sure. I really work hard. But I sit around a lot, stay very late. I smoke and read The New York Times, porno books, How to Build a Patio Roof. Mostly I just look out the window at the house next door, where we used to live. 2129 1/2 Russell Street. I look at the tree that grows wooden pears Ter used to shoot at. The wooden fence glistens with BBs. The BEKINS sign that lit our bed at night. I miss Ter and I smoke. You can’t hear the trains during the day.

From Lucia Berlin’s short story “A Manual for Cleaning Women.” Collected in A Manual for Cleaning Women.

I just finished Stendhal’s novel The Charterhouse of Parma, which is mostly about the problems of aristocrats. Digging into Berlin’s lovely dirty stories feels like an antidote. Balzac said that Stendhal’s novel contained a book on every page; each paragraph in Berlin is like its own little film: “Come and blueberry jelly on the sheets. Racing forms and cigarette butts in the bathroom…Drawings by Andrea with Love to Mom. Pizza crusts. I clean their coke mirror with Windex.” Good lord.

An Interview with Novelist Brian Hall About His Contribution to Waywords and Meansigns, the Unabridged Musical Adaptation of Finnegans Wake

Author Brian Hall is known for his diverse subject matter. His 2003 novel I Should Be Extremely Happy In Your Company is a fictionalized account of Lewis and Clark, and his 2008 novel The Fall of Frost re-imagines Robert Frost’s personal life and inner world. Hall’s writing has received significant praise over the years; his 1997 coming-of-age novel The Saskiad has been translated into twelve languages.

This year Hall collaborated with composer Mary Lorson for a rather unusual endeavor: setting James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake to music. Part of the Waywords and Meansigns project, Hall and Lorson were tasked with creating an unabridged musical version of the Wake’s famous eighth chapter. The chapter presents a dialogue between two women, who are in turn juxtaposed with Dublin’s Liffey river and one of the book’s main characters, Anna Livia Plurabelle. (You can hear their chapter in the embedded audio player below.)

Derek Pyle, who runs Waywords and Meansigns, spoke with Brian Hall about a number of topics ranging from the experience of wrestling with Joyce’s text to the process of writing and researching novels.

Brian Hall: We decided that I would record the voice track first, before she did anything else. I’ve never recorded any reading before, so we practice recorded the thing twice, just to get me used to it. That way I could get used to just how thorny it is to read at a relatively quick pace, to manage to spit out all of these weird words one after another. You have to practice quite a lot so you can get through a sentence and make it sound somewhat natural.

I assured Mary right at the beginning that the final mix and music, all of that would be entirely up to her and I wasn’t going to interfere. I made some suggestions, just throwing out ideas — I know [classical music] pretty well, and she was interested in drawing on that, so I mentioned a few things that could be related.

Derek Pyle: At times your voice has a call and response feel — it was her tinkering that created this effect?

Brian Hall: The chapter is clearly some kind of a dialogue, but a lot of it is not really clear which voice is which. I was looking online and nobody really agrees on how the voices divide. I made my own version of the back and forth, just by highlighting the younger voice, and I gave Mary a copy of this marked up version of the text.

When I read it in the studio in Toronto, it was all on one track. As I read, every time I went to the younger voice I pitched my voice a little bit higher. So with the pitch between the two voices, and my printed version, which had highlighted the young woman’s lines, Mary could tell pretty easily which was which. She put the voices on two different tracks, one on the left speaker, one on the right speaker, and did everything that we hear. It really gives a much better feel.

Derek Pyle: It’s such a full landscape of sound, with the river running through the conversation. What were some of the other underlying conceptual elements guiding your reading?

Brian Hall: Because I tend to gather books, I already had the Tindall guide to Finnegans Wake and I also had the Roland McHugh Annotations to Finnegans Wake. I read through both the Tindall and the McHugh related to this chapter, to see whatever there was — things that I couldn’t figure out on my own.

Since Joyce uses — I can’t remember the figure — 140 different river names, McHugh notes pretty much every time there’s a river name. He doesn’t say which country it’s in, so I marked all of this up and then for all the river names I looked them up on Google Maps.

I wanted to find out what country the rivers are in, because you don’t really have a sense how to pronounce it unless you know what language it’s in. When you’re reading [the Wake] out loud you want to straddle, as much as possible, the different possible pronunciations of these multilingual words.

But I don’t really know how Joyce pronounced some of those words. He may have had a Dublin-English version of it. A lot of it is total guesswork but it was really fun, although a fair amount of work — with a text like this you basically have stuff all over the page, with arrows trying to figure out what the hell you’re doing.

Derek Pyle: What was your engagement with Joyce prior to this undertaking?

Brian Hall: By the time I got out of college I had read most of Joyce except Finnegans Wake. I cheated a bit — I took a course on Ulysses and I ran out of time in the course, the way you do in college, and I ended up only reading about half of Ulysses. I wrote a paper on the part that I had read, to hide the fact that I hadn’t read the whole thing.

When I was forty, I went back and read the entire Ulysses, and like loads of writers I was pretty fascinated. Large parts of it are some of the most interesting stuff written in the 20th century, I think.

But it’s true for a lot of great work, one of the things that makes them so fascinating — as you approach them as a critical reader and as a writer yourself, it makes sense that there are things that you don’t entirely agree with. There are parts of Ulysses which I think go farther down the formalistic path than is really helpful. I never much liked the “Oxen of the Sun” chapter, the one that goes through the history of the English language.

I think a lot of Ulysses, as great as it is, it’s a little longer than ideal. But you know, it’s a fabulous monumental work. When people pick it as like, if you’re forced to choose the greatest novels of the 20th century, I’m certainly not surprised that a lot of people pick Ulysses.

Portrait of the Artist I’ve probably read three or four times. Dubliners you of course get in high school and I read it again in my forties. I read Stephen Hero at one point because I was curious to see the earlier version of Portrait of the Artist.

But Finnegans Wake was the big thing that I had never gotten around to. I actually have you to thank — it really was an opportunity for me to do something I’d wanted to do, which is to take a closer look at one part of the Wake. I always wondered how to what extent I would appreciate what his goals are in Finnegans Wake.

Derek Pyle: How would you articulate Joyce’s goals?

I can only speak of the Liffey chapter, but I think he goes further down the path of playing with language, to the point where it starts to become a question of diminishing returns. I want to stress how much I enjoyed reading it out loud — it is a fascinating word fest he’s done.

But he has the idea that [the chapter] is going to be about rivers — about a river, the Liffey. He has what I think are loads of great ideas about how to do this, where Liffey and Livia are basically the same. The way he describes the places where the Liffey runs and the kinds of landscape it runs through — he does it in such a way that pretty much every moment is both about the river but also about this sort of mythical female figure, Livia. I think a lot of that is really great.

Then there’s this other side of Joyce — and this is the part where I as an artist part ways with him — since he’s doing a thing about the river, he decides to incorporate into the chapter the names of like 140 rivers from around the world. I think that layer just gets in the way; I can’t see that it adds much.

Who am I, of course — I’m just me and he’s James Joyce. If I were his childhood friend and he took any advice from me, I would say “hey Jim, maybe that one layer…”

Derek Pyle: As a writer reading Joyce, is there any way his works have influenced your own craft in terms of techniques to use, or even to avoid?

The generally broad idea of stream of consciousness narration, which of course takes many forms, but he was obviously one of the big fat originators of it. That’s had a big effect on the way I write. I believe very strongly that prose should take whatever form it needs to take, to properly convey the way a person is thinking.

All of my writing, except for my first novel, is in close third person. But I think the writer whose style of stream of consciousness influenced me somewhat more than Joyce — but of course she herself was influenced by Joyce and vice versa — was Virginia Woolf. Her approach in Mrs. Dalloway is the way I tend to write when I’m trying to convey the moment of thought in one of my character’s minds.

I think a big problem with a lot of literary writing today is that a lot of writers consistently stick to a polished lyrical style. I guess it’s out of the idea that beautiful writing is always beautiful, so why not write beautifully. My temperament or whatever, my reading of that, it’s not psychologically acute writing because it doesn’t reflect emotional turmoil.

If you’re describing a character who is very upset or angry or confused, or if the character is not very literate — I think the prose should always try to reflect the content, and that means loads of good prose is not beautiful.

You know Joyce, a lot of his stuff is of course beautiful in its own way, but you get to the “Sirens” chapter in Ulysses and you have this overture section at the beginning. It’s just totally fractured. He’s not trying something beautiful there, he’s trying something much more interesting.

Derek Pyle: Whether it’s Woolf or Joyce, did you take a research approach into looking at technique, breaking down how and why does this work?

Brian Hall: I haven’t sat down and analyzed it. Stuff that I read that really excites me, I just assume it’s working its way into how I think about writing. I do lots of research for my novels, but it’s not related to stylistic stuff.

The novel I’m working on right now, the main character is an astronomer. My sense is, if you’re going to write a novel where the main character is an astronomer, you really should know a lot about astronomy. It’s not like you need lectures in there about astronomy, but just in the background of your mind, you should know a lot because that’s how your character will look at the world.

It helps if you like to do research for its own sake, because then you don’t have the temptation to try to shoehorn too much into the novel. It doesn’t feel like a waste to me if I have twenty times more material than I actually put into the book. I love research, so I don’t regret that at all.

Derek Pyle: Anything else you want to add? Biblioklept interviews usually end with the question ‘have you ever stolen a book?’

Brian Hall: I’ll say this. I really detest copyright law in general and in the U.S. in particular and these organizations like creative commons — what you’re doing with this whole project, where stuff is put online for people to freely download, I just think it’s great.

My understanding of the original idea of copyright law, for one thing it only lasted for sixteen years when it was first proposed by Jefferson. The idea was to keep people from competing in the market with the original thing.

But when you take something, and you change it dramatically by adding things — I ran into this with my Frost book. I ended up not being able to quote certain Frost poems because of supposed copyright problems. That’s a real perversion of the original idea of copyright protection. What I was doing in the Frost book would in no conceivable way cut into the sales of volumes of poetry by Frost.

I personally sympathize with people who are alive and remember Frost and are uncomfortable with the idea of a novelist like me coming along and writing a very personal novel about Frost. I don’t think it’s ridiculous that they don’t like it. But if it weren’t for the ridiculously extended copyright laws in this country, there wouldn’t be a problem. I’d be allowed to do what I do, they could be unhappy about it the way that I’m unhappy about lots of things, and you know, we would just move on.

Oh, and to answer your question, I’ve never stolen a book.

The Garden of Eden, Ernest Hemingway’s Tale of Doomed Polyamory

In general, I dislike reviews that frontload context—get to the book, right? So here’s a short review of Ernest Hemingway’s The Garden of Eden: it is stranger than most of what Hemingway wrote, by turns pleasant, uncomfortable, bewildering, and beautiful. And readable. It’s very, very readable. Young people (or older folks; let’s not be prejudiced) working their way through Hemingway shouldn’t put The Garden of Eden on the back-burner in favor of his more famous works, and anyone who might have written off Hemingway as unreflective macho bravado should take a look at some of the strange gender games this novel has to offer. So, that’s a recommendation, okay?

Now on to that context, which I think is important here. See, The Garden of Eden is one of those unfinished novels that get published posthumously, put together by editors and publishers and other book folk, who play a larger role than we like to admit in the finished books we get from living authors anyway. For various reasons, cultural, historical, etc., we seem to favor the idea of the Singular Artistic Genius who sculpts beauty and truth out of raw Platonic forms that only he or she can access (poor tortured soul). The reality of how our books get to us is a much messier affair, and editors and publishers and even literary studies departments in universities have a large hand in this process, one we tend to ignore in favor of the charms of a Singular Artistic Genius. There’s a fascinating process there, but also a troubling one. Editing issues complicate our ideals of (quite literally) stable authority—is this what the author intended?, we ask (New Critics be damned!). David Foster Wallace and Michael Pietsch, Raymond Carver and Gordon Lish, Franz Kafka and Max Brod, Mary Shelley and Percy Shelley . . . not to mention Shakespeare, Chaucer, Beowulf, The Bible, Homer, etc. etc. etc. But you’re here to read about The Garden of Eden, right gentle reader? Mea culpa. I’ve been blathering away. Let me turn the reins over to the estimable talents of E.L. Doctorow, who offers the following context in his 1986 review of the book in The New York Times—

Since Hemingway’s death in 1961, his estate and his publishers, Charles Scribner’s Sons, have been catching up to him, issuing the work which, for one reason or another, he did not publish during his lifetime. He held back ”A Moveable Feast” out of concern for the feelings of the people in it who might still be alive. But for the novel ”Islands in the Stream” he seems to have had editorial misgivings. Even more deeply in this category is ”The Garden of Eden,” which he began in 1946 and worked on intermittently in the last 15 years of his life and left unfinished. It is a highly readable story, if not possibly the book he envisioned. As published it is composed of 30 short chapters running to about 70,000 words. A publisher’s note advises that ”some cuts” have been made in the manuscript, but according to Mr. Baker’s biography, at one point a revised manuscript of the work ran to 48 chapters and 200,000 words, so the publisher’s note is disingenuous. In an interview with The New York Times last December, a Scribners editor admitted to taking out a subplot in rough draft that he felt had not been integrated into the ”main body” of the text, but this cut reduced the book’s length by two-thirds.

So, yeah. The version we have of The Garden of Eden is heavily cut, and also likely heavily arranged. But that’s what editors do, and this is the book we have (for now, anyway—it seems like on the year of its 25th anniversary of publication, and the 50th anniversary of Hemingway’s death that Scribner should work toward putting out an unedited scholarly edition) — so I’ll talk about that book a bit.

The Garden of Eden tells the story of a few months in the lives of a young newlywed couple, David Bourne, an emerging novelist, and his wife Catherine, a trust fund baby flitting about Europe. The novel is set primarily on the French Riviera, in the thin sliver of high years between the two big wars. David and Catherine spend most of their days in this Edenic setting eating fine food and making love and swimming and riding bikes and fishing. And drinking. Lots and lots of drinking. Lots of drinking. It all sounds quite beautiful—h0w about a taste?

On this morning there was brioche and red raspberry preserve and the eggs were boiled and there was a pat of butter that melted as they stirred them and salted them lightly and ground pepper over them in the cups. They were big eggs and fresh and the girl’s were not cooked quite as long as the young man’s. He remembered that easily and he he was happy with his which he diced up with the spoon and ate with only the flow of the butter to moisten them and the fresh early morning texture and the bite of the coarsely ground pepper grains and the hot coffee and the chickory-fragrant bowl of café au lait.

Hemingway’s technique throughout the novel is to present the phenomenological contours of a heady world. It’s lovely to ride along with David and Catherine, rich and free and beautiful.

Their new life together is hardly charmed, however. See, Catherine gets a haircut—

Her hair was cropped as short as a boy’s. It was cut with no compromises. It was brushed back, heavy as always, but the sides were cut short and the ears that grew close to her head were clear and the tawny line of her hair was cropped close to her head and smooth and sweeping back. She turned her head and lifted her breasts and said, “Kiss me please.” . . .

“You see, she said. “That’s the surprise. I’m a girl. But now I’m a boy too and I can do anything and anything and anything.”

“Sit here by me,” he said. “What do you want, brother.”

David’s playful response—calling his wife “brother”—covers up some of his shock and fear, but it also points to his underlying curiosity and gender confusion. And indeed, Catherine’s new haircut licenses her to “do anything and anything and anything” — beginning with some strange bed games that night—

He had shut his eyes and he could feel the long light weight of her on him and her breasts pressing against him and her lips on his. He lay there and felt something and then her hand holding him and searching lower and he helped with his hands and then lay back in the dark and did not think at all and only felt the weight and the strangeness inside and she said, “Now you can’t tell who is who can you?”

“No.”

“You are changing,” she said. “Oh you are. You are. Yes you are and you’re my girl Catherine. Will you change and be my girl and let me take you?”

“You’re Catherine.”

“No. I’m Peter. You’re my wonderful Catherine. You’re my beautiful, lovely Catherine. You were so good to change. Oh thank you, Catherine, so much. Please understand. Please know and understand. I’m going to make love to you forever.”

David, partial stand-in for Hemingway, transforms into a girl who feels “something” during sex with Catherine (or, ahem, Peter)—note that that “something” has no clear referent. As their gender inverting games continue (much to David’s horror), Hemingway’s usually concrete language retreats to vague proforms without referents, “it”s without antecedents; his usually precise diction dissolves in these scenes, much as the Bournes’ marriage dissolves each time Catherine escalates the gender inversion. David gives her the nickname “Devil,” as if she were both Eve and Serpent in their Garden. Catherine’s transformations continue as she cuts her hair back even more, and sunbathes all the time so that she can be as dark as possible. She dyes her hair a silver blonde and makes David get his hair cut and dyed the same.

The bizarre behavior (shades of Scott and Zelda?) culminates in Catherine introducing another woman into the marriage. Marita falls in love with both David and Catherine, but her lesbian sex with Catherine only accelerates the latter’s encroaching insanity. David is initially radically ambivalent to the ménage à trois proposed by his wife; he has the good sense to see that a three-way marriage is ultimately untenable and that his wife is going crazy. He vacillates between hostility and love for the two women, but eventually finds a support system in Marita as it becomes increasingly apparent (to all three) that Catherine is depressed and mentally unstable, enraged that David has ceased to write about the pair’s honeymoon adventures on the Riviera. Catherine has been bankrolling David; jealous of good reviews from his last novel, she insists that he write only their story, but David would rather write “the hardest story” he knows—the story of his childhood in East Africa with his father, a big game hunter.

In some of the most extraordinary passages of The Garden of Eden, David writes himself into his boyhood existence, trailing a bull elephant with his father through a jungle trek. David has spotted the elephant by moonlight, prompting his father and his father’s fellow tracker and gun bearer Juma to hunt the old beast. As they trail the animal, David begins to realize how horrible the hunt is, how cruel it is to kill the animal for sport. The passages are somewhat perplexing given Hemingway’s reputation as a hunter. Indeed, this is one of the major features of The Garden of Eden: it repeatedly confounds or complicates our ideas about Hemingway the man’s man, Hemingway the writer, Hemingway the hunter. David describes the wounded, dying elephant—

They found him anchored, in such suffering and despair that he could no longer move. He had crashed through the heavy cover where he had been feeding and crossed a path of open forest and David and his father had run along the heavily splashed blood trail. Then the elephant had gone on into thick forest and David had seen him ahead standing gray and huge against the trunk of a tree. David could only see his stern and then his father moved ahead of him and he followed and they came alongside the elephant as though he was a ship and David saw the blood coming from his flanks and running down his sides and then his father raised his rifle and fired and the elephant turned his head with the great tusks moving heavy and slow and looked at them and when his father fired the second barrel the elephant seemed to sway like a felled tree and came smashing down toward them. But he was not dead. He had been anchored and now he was down with his shoulder broken. He did not move but his eye was alive and looked at David. He had very long eyelashes and his eye was the most alive thing David had ever seen.

David succeeds in writing this “hard” story, and the passages are remarkable in their authenticity—David’s story is a good story, the highlight of the book perhaps; it’s not just Hemingway telling us that David wrote a great story, we actually get to experience the story itself as well as the grueling process by which it was made. Hemingway and his surrogate David show us—make us experience—how difficult writing really is, and then share the fruit of that labor with us. These scenes raise the stakes of The Garden of Eden, revealing how serious David is when he remarks (repeatedly) that the writing is the most important thing—that it outweighs love, it surpasses his marriage. These realizations freight the climax of the novel all the more heavily, but I will avoid anymore spoilers.

The Garden of Eden has some obvious flaws. Marita is underdeveloped at best for such an important character, and her love for David and Catherine remains unexplored, and in fact barely remarked upon. The biggest problem with the book is its conclusion, which feels too pat, too obvious for such a strange, amorphous book. It is here that the presence of an editorial hand seems clearest, to the extent that I wonder if the short little chapter that concludes the novel wasn’t cobbled together from a few stray sentences throughout the manuscript. But The Garden of Eden, despite some shortcomings, is a book well worth reading. The novel complicates not just Hemingway’s reputation, but also our sense of Hemingway’s sense of himself. Recommended.

[Ed. note: Biblioklept originally published a version of this review in August of 2011]

A short report from The Charterhouse of Parma

Have you read Honoré de Balzac’s 1833 novel Eugénie Grandet?

I haven’t, but I’ve read the Wikipedia summary.

I’ve also read, several times, Donald Barthelme’s 1968 parody, “Eugénie Grandet,” which is very very funny.

Have you read Stendhal’s 1839 novel The Charterhouse of Parma?

After repeated false starts, I seem to be finishing it up (I’m on Chapter 19 of 28 of Richard Howard’s 1999 Modern Library translation).

I brought up Eugénie Grandet (Balzac’s) to bring up “Eugénie Grandet” (Barthelme’s). Stendhal’s (1830’s French) novel Charterhouse keeps reminding me of Barthelme’s (1960’s American) short story “Eugénie Grandet,” which is, as I’ve said, a parody of Honoré de Balzac’s (1830’s French) novel Eugénie Grandet. Balzac and Stendhal are pre-Modernists (which is to say they were modernists, I suppose). Donald Barthelme wanted to be a big em Modernist; his postmodernism was inadvertent. By which I mean— “postmodernism” is just a description (a description of a description really, but let me not navelgaze).

Well and so: I find myself often bored with The Charterhouse of Parma and wishing for a condensation, for a Donald Barthelme number that will magically boil down all its best bits into a loving parody that retains its themes and storylines (while simultaneously critiquing them)—a parody served with an au jus of the novel’s rich flavor.

My frequent boredom with the novel—and, let me insert here, betwixt beloved dashes, that one of my (many) favorite things about Charterhouse is that it is about boredom! that phrases like “boredom,” boring,” and “bored” repeat repeatedly throughout it! I fucking love that! And Stendhal, the pre-Modernist (which is to say “modernist”), wants the reader to feel some of the boredom of court intrigue (which is not always intriguing). The marvelous ironic earnest narrator so frequently frequents phrases like, “The reader will no doubt tire of this conversation, which went on for like two fucking hours” (not a direct quote, although the word “fuck” shows up a few times in Howard’s translation. How fucking Modern!)—okay—

My frequent boredom with the novel is actually not so frequent. It’s more like a chapter to chapter affair. I love pretty much every moment that Stendhal keeps the lens on his naive hero, the intrepid nobleman Fabrizio del Dongo. In love with (the idea of) Napoleon (and his aunt, sorta), a revolutionist (not really), a big ell Liberal (nope), Fabrizio is a charismatic (and callow) hero, and his chapters shuttle along with marvelous quixotic ironic energy. It’s picaresque stuff. (Fabrizio reminds me of another hero I love, Candide). Fabrizio runs away from home to join Napoleon’s army! Fabrizio is threatened with arrest! Fabrizio is sorta exiled! Fabrizio fucks around in Naples! Fabrizio joins the priesthood! Fabrizio might love love his aunt! Fabrizio fights a duel! Fabrizio kills a man! (Not the duel dude). Fabrizio is on the run (again)! Fabrizio goes to jail! Fabrizio falls in love!

When it’s not doing the picaresque adventure story/quixotic romance thing (which is to say, like half the time) Charterhouse is a novel of courtly intrigues and political machinations (I think our boy Balzac called it the new The Prince). One of the greatest strengths of Charterhouse is its depictions of psychology, or consciousness-in-motion (which is to say Modernism, (or pre-modernism)). Stendhal takes us through his characters’ thinking…but that can sometimes be dull, I’ll admit. (Except when it’s not). Let me turn over this riff to Italo Calvino, briefly, who clearly does not think the novel dull, ever—but I like his description here of the books operatic “dramatic centre.” From his essay “Guide for New Readers of Stendhal’s Charterhouse“:

All this in the petty world of court and society intrigue, between a prince haunted by fear for having hanged two patriots and the ‘fiscal général’ (justice minister) Rassi who is the incarnation (perhaps for the first time in a character in a novel) of a bureaucratic mediocrity which also has something terrifying in it. And here the conflict is, in line with Stendhal’s intentions, between this image of the backward Europe of Metternich and the absolute nature of those passions which brook no bounds and which were the last refuge for the noble ideals of an age that had been overcome.

The dramatic centre of the book is like an opera (and opera had been the first medium which had helped the music-mad Stendhal to understand Italy) but in The Charterhouse the atmosphere (luckily) is not that of tragic opera but rather (as Paul Valéry discovered) of operetta. The tyrannical rule is squalid but hesitant and clumsy (much worse had really taken place at Modena) and the passions are powerful but work by a rather basic mechanism. (Just one character, Count Mosca, possesses any psychological complexity, a calculating character but one who is also desperate, possessive and nihilistic.)

I disagree with Calvino here. Mosca is an interesting character (at times), but hardly the only one with any psychological complexity. Stendhal is always showing us the gears ticking clicking wheeling churning in his characters’ minds—Fabrizio’s Auntie Gina in particular. (Ahem. Excuse me–The Duchessa).

But Duchess Aunt Gina is a big character, perhaps the secret star of Charterhouse, really, and I’m getting read to wrap this thing up. So I’ll offer a brief example rather from (what I assume is ultimately) a minor character, sweet Clélia Conti. Here she is, in the chapter I finished today, puzzling through the puzzle of fickle Fabrizio, who’s imprisoned in her dad’s tower and has fallen for her:

Fabrizio was fickle; in Naples, he had had the reputation of charming mistresses quite readily. Despite all the reserve imposed upon the role of a young lady, ever since she had become a Canoness and had gone to court, Clélia, without ever asking questions but by listening attentively, had managed to learn the reputations of the young men who had, one after the next, sought her hand in marriage; well then, Fabrizio, compared to all the others, was the one who was least trustworthy in affairs of the heart. He was in prison, he was bored, he paid court to the one woman he could speak to—what could be simpler? What, indeed, more common? And this is what plunged Clélia into despair.

Clélia’s despair is earned; her introspection is adroit (even as it is tender). Perhaps the wonderful trick of Charterhouse is that Stendhal shows us a Fabrizio who cannot see (that he cannot see) that he is fickle, that Clélia’s take on his character is probably accurate—he’s just bored! (Again, I’ve not read to the end). Yes: What, indeed, could be more common? And one of my favorite things about Charterhouse is not just that our dear narrator renders that (common) despair in real and emotional and psychological (which is to say, um Modern) terms for us—but also that our narrator takes a sweetly ironic tone about the whole business.

Or maybe it’s not sweetly ironic—but I wouldn’t know. I have to read it post-Barthelme, through a post-postmodern lens. I’m not otherwise equipped.

Bored of Hell

I am bored of Hell, Henri Barbusse’s 1908 novel of voyeurism.

Maybe I should blame the 1966 English translation (from the French) by Robert Baldick, which often feels stuffily stuffy for a book about “childbirth, first love, marriage, adultery, lesbianism, illness, religion and death” (as our dear translator puts it in his brief preface). Maybe I should blame it on Baldick, but that seems rash and wrong, and I have no basis of comparison, do I?

So I blame it on myself, this boredom of Hell.

Why write then? Why not write it off, rather, which is to say, do not write—I don’t know.

I’m bored with Hell and there are half a dozen novels I’ve recently read (or am reading) that I should commend, recommend, attempt to write about—but here I am bored of Hell, and writing about it. Maybe it’s—and the it here refers to writing about Hell, a book I confesss a boredom of—maybe it’s because I’ve allowed myself over the last few days to good lord skim the goddamned infernal thing, not skimming for a replenishing sustenance, but rather looking for the juicy fat bits, the best bits, in the same way a teenaged version of myself skimmed Henry Miller and Anaïs Nin in a powerful sweat.

(I was a teenage cliché).

Maybe it’s that the best bits of Hell weren’t juicy enough. (In this novel, an unnamed narrator espies all sorts of sensual (and nonsensual) shenanigans through a small hole in his hotel room). Or maybe the juicy bits were juicy, but the translation dried them out. So many of the sentences made me want to close the book. But it’s unfair for me to write this, I suppose, without offering a sample. Here, from early in the novel, is an excerpt that did make me want to keep going:

The mouth is something naked in the naked face. The mouth, which is red with blood, which is forever bleeding, is comparable to the heart: it is a wound, and it is almost a wound to see a woman’s mouth.

And I begin trembling before this woman who is opening a little and bleeding from a smile. The divan yields warmly to the embrace of her broad hips; her finely-made knees are close together, and the whole of the centre of her body is in the shape of a heart.

…Half-lying on the divan, she stretches out her feet towards the fire, lifting her skirt slightly with both hands, and this movement uncovers her black-stockinged legs.

And my flesh cries out…

Those last ellipses were mine. Did you want more? I did, I admit. And yet after 50 pages, I grew bored. The voyeurism was boring—sprawling. Perhaps I’m lazy. Perhaps I want my voyeurism condensed. Maybe…weirder. I don’t know. Reader, I skimmed. I skimmed, like I said, for morsels—but also to the end, the the final chapter, to the final exquisite not boring paragraph, which I’ll share with you now before “I have done,” as the narrator states in this final section. Promised paragraph:

I believe that confronting the human heart and the human mind, which are composed of imperishable longings, there is only the mirage of what they long for. I believe that around us there is only one word on all sides, one immense word which reveals our solitude and extinguishes our radiance: Nothing! I believe that the word does not point to our insignificance or our unhappiness, but on the contrary to our fulfillment and our divinity, since everything is in ourselves.

The empty frame where the image of the author is supposed to be (Elena Ferrante)

Evidently, in a world where philological education has almost completely disappeared, where critics are no longer attentive to style, the decision not to be present as an author generates ill will and this type of fantasy. The experts stare at the empty frame where the image of the author is supposed to be and they don’t have the technical tools, or, more simply, the true passion and sensitivity as readers, to fill that space with the works. So they forget that every individual work has its own story. Only the label of the name or a rigorous philological examination allows us to take for granted that the author of Dubliners is the same person who wrote Ulysses andFinnegans Wake. The cultural education of any high school student should include the idea that a writer adapts depending on what he or she needs to express. Instead, most people think anyone literate can write a story. They don’t understand that a writer works hard to be flexible, to face many different trials, and without ever knowing what the outcome will be.

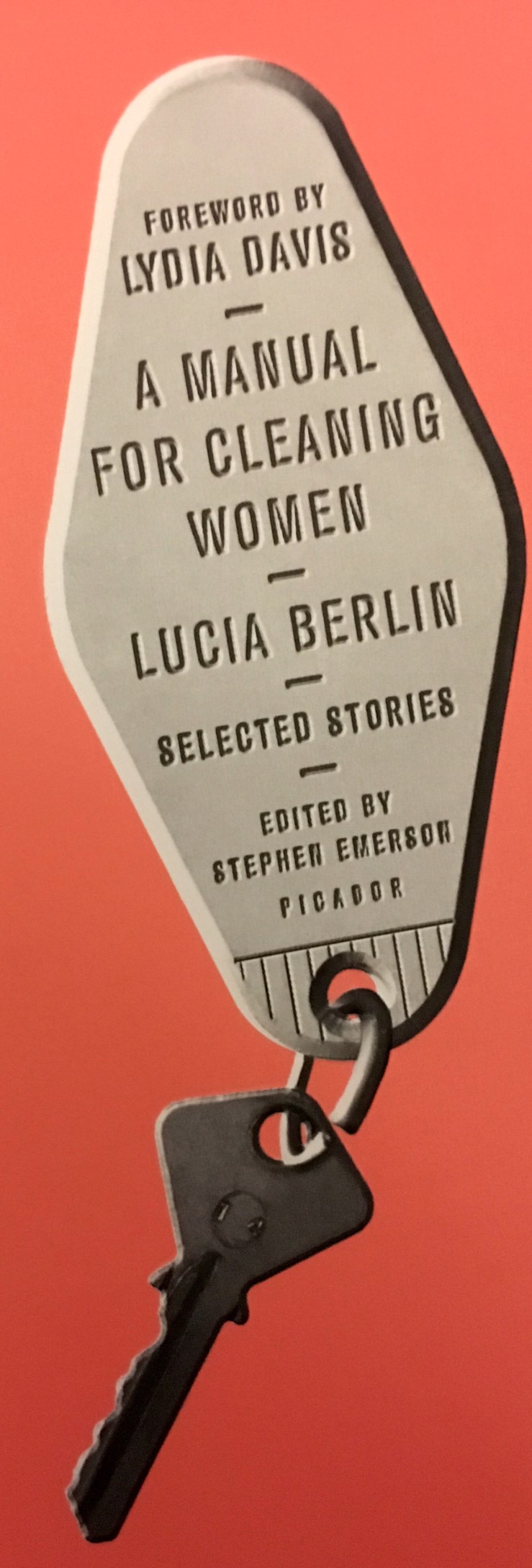

The quest is fun, the walking in the dark is fun | Yuri Herrera interviewed at 3:AM Magazine

Yuri Herrera was interviewed by Tristan Foster at 3:AM Magazine a few weeks ago. Herrera’s new novella (or “new” in English translation by Lisa Dilman, anyway) is The Transmigration of Bodies and it’s really, really good. I read most of it in one sitting a few months back, and I owe it a proper review. Herrera’s previous novella, Signs Preceding the End of the World, was one of my favorite books published last year.

3:AM: Despite both the seriousness of its themes and the apocalyptic backdrop, Transmigration is full of an absurd kind of fun. I’m thinking here, for instance, of the scene at the strip club; the strippers have taken off everything except for their facemasks, but they use the allure of removing the masks to excite the men watching. Is this writing fun? Is fun crucial to this kind of writing?

YH: The quest is fun, the walking in the dark is fun. To create your own paths in a room without light. Of course, this sometimes is also frustrating, when you just keep bumping into things, most commonly into my own very clumsy self. Eventually you discover that you have not been walking completely in the dark but with some sort of intuitive sense of direction, some creative spine. But until you discover that, you alternate between the joy and the anxiety and puzzling with words.

Nathaniel Hawthorne’s journal entry for July 13th, 1837

Thursday, July 13th.–Two small Canadian boys came to our house yesterday, with strawberries to sell. It sounds strangely to hear children bargaining in French on the borders of Yankee-land. Among other languages spoken hereabouts must be reckoned the wild Irish. Some of the laborers on the mill-dam can speak nothing else. The intermixture of foreigners sometimes gives rise to quarrels between them and the natives. As we were going to the village yesterday afternoon, we witnessed the beginning of a quarrel between a Canadian and a Yankee,–the latter accusing the former of striking his oxen. B—- thrust himself between and parted them; but they afterwards renewed their fray, and the Canadian, I believe, thrashed the Yankee soundly–for which he had to pay twelve dollars. Yet he was but a little fellow.

Coming to the Mansion House about supper-time, we found somewhat of a concourse of people, the Governor and Council being in session on the subject of the disputed territory. The British have lately imprisoned a man who was sent to take the census; and the Mainiacs are much excited on the subject. They wish the Governor to order out the militia at once and take possession of the territory with the strong hand. There was a British army-captain at the Mansion House; and an idea was thrown out that it would be as well to seize upon him as a hostage. I would, for the joke’s sake, that it had been done. Personages at the tavern: the Governor, somewhat stared after as he walked through the bar-room; Councillors seated about, sitting on benches near the bar, or on the stoop along the front of the house; the Adjutant-General of the State; two young Blue-Noses, from Canada or the Provinces; a gentleman “thumbing his hat” for liquor, or perhaps playing off the trick of the “honest landlord” on some stranger. The decanters and wine-bottles on the move, and the beer and soda founts pouring out continual streams, with a whiz. Stage-drivers, etc., asked to drink with the aristocracy, and my host treating and being treated. Rubicund faces; breaths odorous of brandy-and-water. Occasionally the pop of a champagne cork.

Returned home, and took a lesson in French of Mons. S—- . I like him very much, and have seldom met with a more honest, simple, and apparently so well-principled a man; which good qualities I impute to his being, by the father’s side, of German blood. He looks more like a German–or, as he says, like a Swiss–than a Frenchman, having very light hair and a light complexion, and not a French expression. He is a vivacious little fellow, and wonderfully excitable to mirth; and it is truly a sight to see him laugh;–every feature partakes of his movement, and even his whole body shares in it, as he rises and dances about the room. He has great variety of conversation, commensurate with his experiences in life, and sometimes will talk Spanish, ore rotundo,— sometimes imitate the Catholic priests, chanting Latin songs for the dead, in deep, gruff, awful tones, producing really a very strong impression,–then he will break out into a light, French song, perhaps of love, perhaps of war, acting it out, as if on the stage of a theatre: all this intermingled with continual fun, excited by the incidents of the passing moment. He has Frenchified all our names, calling B—- Monsieur Du Pont, myself M. de L’Aubépine, and himself M. le Berger, and all, Knights of the Round-Table. And we live in great harmony and brotherhood, as queer a life as anybody leads, and as queer a set as may be found anywhere. In his more serious intervals, he talks philosophy and deism, and preaches obedience to the law of reason and morality; which law he says (and I believe him) he has so well observed, that, notwithstanding his residence in dissolute countries, he has never yet been sinful. He wishes me, eight or nine weeks hence, to accompany him on foot to Quebec, and then to Niagara and New York. I should like it well, if my circumstances and other considerations would permit. What pleases much in Mons. S—- is the simple and childlike enjoyment he finds in trifles, and the joy with which he speaks of going back to his own country, away from the dull Yankees, who here misunderstand and despise him. Yet I have never heard him speak harshly of them. I rather think that B—- and I will be remembered by him with more pleasure than anybody else in the country; for we have sympathized with him, and treated him kindly, and like a gentleman and an equal; and he comes to us at night as to home and friends.

I went down to the river to-day to see B—- fish for salmon with a fly,–a hopeless business; for he says that only one instance has been known in the United States of salmon being taken otherwise than with a net. A few chubs were all the fruit of his piscatory efforts. But while looking at the rushing and rippling stream, I saw a great fish, some six feet long and thick in proportion, suddenly emerge at whole length, turn a somerset, and then vanish again beneath the water. It was of a glistening, yellowish brown, with its fins all spread, and looking very strange and startling, darting out so lifelike from the black water, throwing itself fully into the bright sunshine, and then lost to sight and to pursuit. I saw also a long, flat-bottomed boat go up the river, with a brisk wind, and against a strong stream. Its sails were of curious construction: a long mast, with two sails below, one on each side of the boat, and a broader one surmounting them. The sails were colored brown, and appeared like leather or skins, but were really cloth. At a distance, the vessel looked like, or at least I compared it to, a monstrous water-insect skimming along the river. If the sails had been crimson or yellow, the resemblance would have been much closer. There was a pretty spacious raised cabin in the after part of the boat. It moved along lightly, and disappeared between the woody banks. These boats have the two parallel sails attached to the same yard, and some have two sails, one surmounting the other. They trade to Waterville and thereabouts,–names, as “Paul Pry,” on their sails.

Nathaniel Hawthorne’s journal entry for July 13th, 1837. From Passages from the American Note-Books.

Stanley Elkin reviews Stanley Elkin’s novel The Dick Gibson Show (kinda sorta)

[Ed. note: I finished Stanley Elkin’s 1971 novel The Dick Gibson Show a few days ago. I read The Dick Gibson Show immediately after finishing Elkin’s 1976 novel The Franchiser. I want to write something about these novels, which seem of a piece to me, but I also wanted to get a bit more context first, and the most basic of internet searches led me to Elkin’s 1974 interview in The Paris Review with Thomas LeClair.

What follows are selections from the interview in which Elkin kinda sorta analyzes The Dick Gibson Show, providing what I take to be a Very Good and Fascinating Review of the novel.

Look, I went to school for reading books, I learned about the goddamn intentional fallacy and la mort de l’auteur and all that jazz, and I know that the author isn’t supposed to be the goddamn authority on his own work, I know that what follows isn’t a proper review—but I don’t care. I like it.

My assumption is it’s likely that anyone interested enough in a review of The Dick Gibson Show has probably already read Elkin’s Paris Review interview, and would probably prefer, like, something new on the novel. Which I’ll attempt down the line. But for now: Elkin on Elkin—]

INTERVIEWER: I have some questions now about themes or ideas I find in much of your fiction. You have Dick Gibson say, “The point of life was the possibility it always held out for the exceptional.” The heroes in your novels have a tremendous need to be exceptional, to transcend others, to quarrel with the facts of physical existence. Is this a convention—which we’ve just been talking about—or something very basic to your whole view of life?

ELKIN: It is something very basic to my view of life, but in the case of that character it becomes the initial trauma which sets him going. It becomes his priority. Dick Gibson goes on to say that he had believed that the great life was the life of cliché. When I started to write the book, I did not know that was what the book was going to be about, but indeed that is precisely what the book gets to be about as I learned what Dick Gibson’s life meant. Consider the last few pages of the book:

What had his own life been, his interminable apprenticeship which he saw now he could never end? And everyone blameless as himself, everyone doing his best but maddened at last, all, all zealous, all with explanations ready at hand and serving an ideal of truth or beauty or health or grace. Everyone—everyone. It did no good to change policy or fiddle with format. The world pressed in. It opened your windows. All one could hope for was to find his scapegoat . . .

Now, everything that follows this is a cliché:

to wait for him, lurking in alleys, pressed flat against walls, crouched behind doors while the key jiggles in the lock, taking all the melodramatic postures of revenge. To be there in closets when the enemy comes for his hat, or to surprise him with guns in swivel chairs, your legs dapperly crossed when you turn to face him, to pin him down on hillsides or pounce on him from trees as he rides by, to meet him on the roofs of trains roaring on trestles, or leap at him while he stops at red lights, to struggle with him on the smooth faces of cliffs…

and so on. The theme of the novel is that the exceptional life—the only great life—is the trite life. It is something that I believe. It is not something that I am willing to risk bodily injury to myself in order to bring to pass, but to have affairs, to go to Europe, to live the dramatic clichés, all the stuff of which movies are made, would be the great life.

INTERVIEWER: But what if one were aware that they were clichés? Isn’t that what causes so much despair in contemporary fiction—that characters can’t live a life of clichés?

ELKIN: Dick Gibson is aware that they are clichés. What sets him off—what first inspires this notion in him—is his court-martial when he appears before the general and says that he’s taken a burr out of the general’s paw—something that happens in a fairy tale. When Dick realizes what has happened to him, he begins to weep, thinking, oh boy, I’ve got it made—I’m going to have enemies, I’m going to be lonely, I’m going to suffer. That is the theme of that book.

INTERVIEWER: Do the characters in your novels, then, have rather conventional notions of what exceptional is?

ELKIN: Yes, I think so.

Dick can’t stand anybody’s obsession but his own, which is largely the plight of myself and yourself, probably, and everybody. He’s opened a Pandora’s box when he opens his microphones to the people out there. When they find the platform that the Gibson format provides, they just get nuttier and nuttier and wilder and wilder, and this genuinely arouses whatever minimal social consciousness Dick Gibson has. The paradox of the novel is that the enemy that Gibson had been looking for all his life is that audience. The audience is the enemy. Dick builds up in his mind this Behr-Bleibtreau character. That Behr-Bleibtreau is his enemy. That’s baloney paranoia. The enemy is the amorphous public that he is trying to appeal to, that he’s trying to make love to with his voice. Dick Gibson is a bodiless being. He is his voice. That’s why the major scene in the novel is the struggle for Gibson’s voice.

INTERVIEWER: Who is Behr-Bleibtreau? There is a suggestiveness to his name that I can’t articulate.

ELKIN: Neither can I. I used to know a guy named—Bleibtreau. Hyphenating the name made it more sinister than just Bleibtreau itself. You know, you could almost put Count in front of it.

INTERVIEWER: s that why Dick thinks that Behr-Bleibtreau is the enemy—because there is this suggestion of cliché?

ELKIN: That’s right. Behr-Bleibtreau is a charlatan—that’s what he is. He has this theory of the will that is alluded to in the second section of the novel. And he is a hypnotist, exactly the kind of guy who Gibson sees as out to get him. Of course Behr-Bleibtreau isn’t out to get him. When Gibson thinks it is Behr-Bleibtreau calling him from Cincinnati, it isn’t. It’s just Gibson’s own paranoia that creates the conditions for Behr-Bleibtreauism.

INTERVIEWER: Is radio in the novel an index to social change, perhaps the devaluation of language?

ELKIN: That was not my intention. I could make a case that once upon a time there were scripts, a platform and an audience out in front of Jack Benny and Mary Livingstone, that radio then was a kind of art form and now it is an artless form in which you get self-promoters and people with theories about curing cancer by swallowing mosquitoes or something. Language, since it is occurring spontaneously rather than thought out, is devalued. But actually, in real life, modern radio talk shows are much more interesting than The Jack Benny Program ever was because you are getting the shoptalk of personality.

INTERVIEWER: Dick is a professional word man, and by the end he is reduced nearly to silence. Is this your “literature of exhaustion” that Barth talks about, a comment on the futility of language…

ELKIN: No. Certainly not.

INTERVIEWER: He does say less and less as the novel moves along.

ELKIN: Right. And the other people say more and more. That is intentional. But Dick makes an effort to get his program back from the sufferers. He starts hanging up on people. Then he gets the biggest charlatan—Nixon—at the end. Wasn’t I clever to invent Nixon before Nixon did?

INTERVIEWER: In bringing together so many stories and storytellers, did you have a thematic unity in mind?

ELKIN: I had in mind, as a matter of fact, The Canterbury Tales, particularly in that second section where the journey to dawn is the journey to Canterbury. Although there are no particular parallels, when I was sending out sections of the novel to magazines, I would call the sections “The Druggist’s Tale” and so on. There is that choral effect of the pilgrims to Canterbury.

Reading/Have Read/Should Write About

From bottom to top:

I had to go hunt through the house for the trio of Hildafolk comics by Luke Pearson because my kids keep swapping them around. We’ve read them a bunch of times now and they are very good and sweet and charming and you can get them from Nobrow. Hilda is going to be a Netflix series, by the way, which I told my kids and they were psyched. (They ten went on Netflix and looked for it. I had to explain production schedules).

W.D. Clarke’s White Mythology (which may or may not take its title from Derrida’s essay of the same name) is actually two novellas, Skinner Boxed and Love’s Alchemy. I finished the first novella before July 4th; Skinner Boxed is about psychiatrist Dr. Ed, who juggles a bunch of maguffins including a detached (and missing) wife, a returned bastard son, and a clinical anti-depressant trial. The novella begins with epigrams from Gravity’s Rainbow and A Christmas Carol, the latter of which it (somewhat perhaps ironically) follows. I finished the second novella Love’s Alchemy yesterday. Its tone is not as zany as that of Skinner Boxed, but both stories require the reader to put together seemingly disconnected events for the plot to “resolve” (if resolve is the right word). Good stuff.