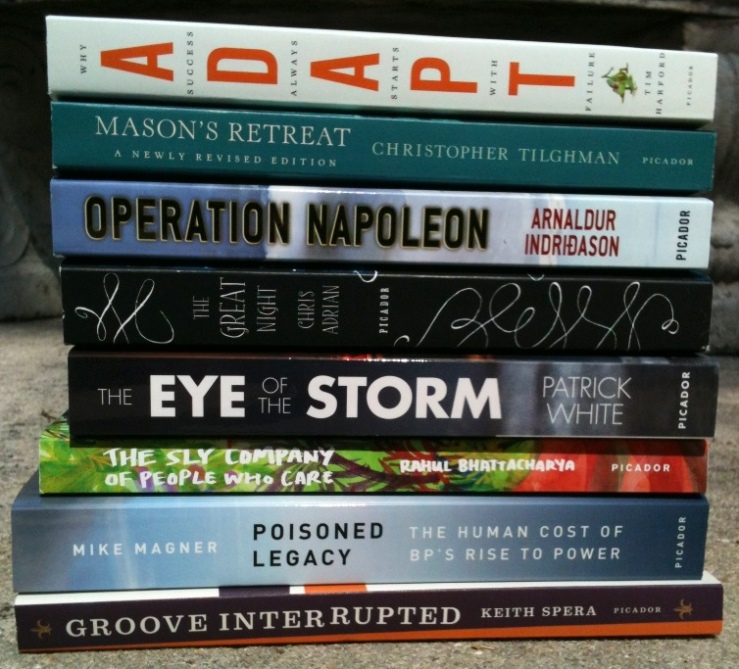

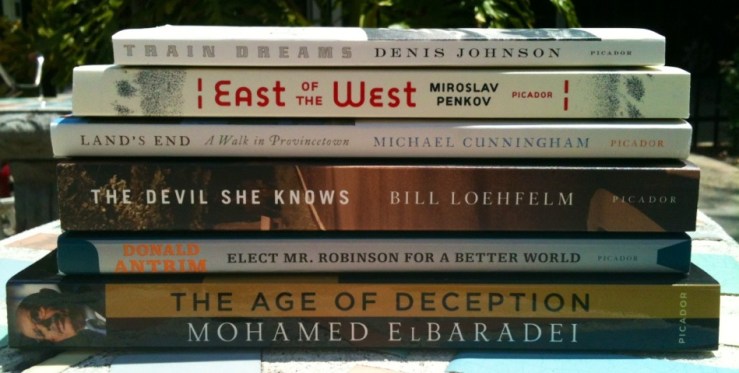

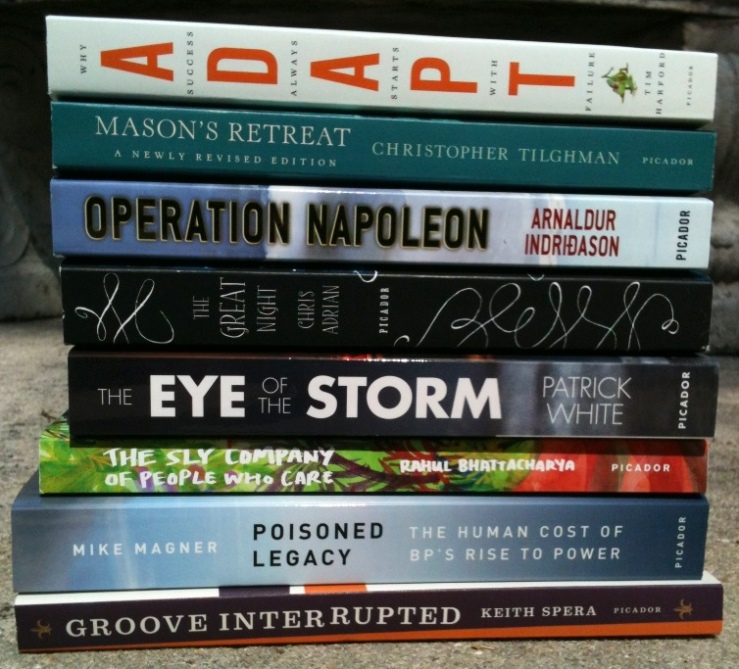

Nice little stack from the good people at Picador—novels, reissues, first-time-in-trade-paperbacks, nonfiction . . . a nice little spread.

Nice little stack from the good people at Picador—novels, reissues, first-time-in-trade-paperbacks, nonfiction . . . a nice little spread.

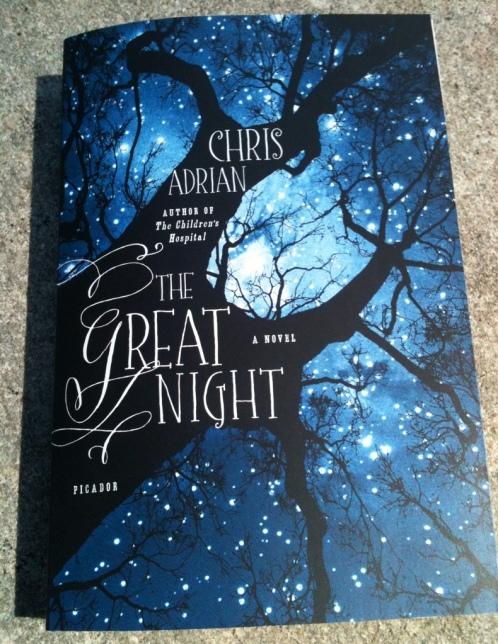

First up is Chris Adrian’s latest novel The Great Night, which, improbably, I’ve yet to read—I’m a huge fan of Chris Adrian’s other books, especially The Children’s Hospital (although I’ve reviewed his other books here too, for those inclined to hit the archives), and I love A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which I know The Great Night basically riffs on. Anyway, my wife snapped this one up right away (I had to go through her nightstand to fetch it up for yon photograph), so my reading will be delayed (although I will likely con her into reviewing it here).

From Patrick Ness’s review at The Guardian—

The Great Night is set in Buena Vista Park in San Francisco. Titania and Oberon – the very ones from Shakespeare’s play – live under the park’s main hill with their full court. Puck is there too, a malevolent but chained force, chafing for revenge against his masters. He may get his chance, for Titania is collapsing under grief. Boy, a changeling brought in by Oberon to amuse her and for whom she felt the first maternal feelings of her immortal life, has died of a very human disease, leukaemia.

Consumed by the pain of her loss, Titania makes a terrible mistake and tells Oberon she never loved him. Furious, he abandons her and shows no signs of returning. But perhaps if Titania releases Puck, who the other faeries refer to as the Beast, then Oberon will have to return to enslave him again. Won’t he? She breaks Puck’s bonds on the Great Night – Midsummer’s Eve, naturally – for which he says, “Milady, I am in your debt, and so I shall eat you last.” . . .

. . . Adrian does nearly everything right here. The Shakespearean references are worn lightly, and the plotting is so skilful you barely notice it falling into place. The characterisations are rich, too. There’s a spellbinding chapter on Molly’s childhood in a performing Christian family band that is both deeply weird and blisteringly sad. Plus there’s an eye-wateringly matter-of-fact approach to sex (and lots of it), which here is essentially indistinguishable from magic, and from love as well, in all its “intimations from the world that there was more to be had, something different and something better”.

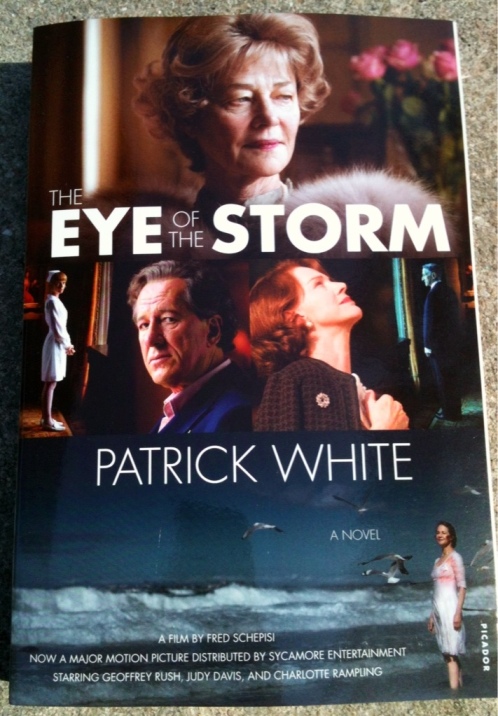

I like the cover of the Adrian, which I only mention here to transition into The Eye of the Storm, the novel that won Patrick White the Nobel in 1973. The book has been adapted into a film, so of course there’s a reissue with a film tie-in cover. (Buzzfeed’s addressed this phenomena recently; I did it a few years ago myself).

Speaking of covers: Love love love this one for The Sly Company of People Who Care by Rahul Bhattacharya:

Here’s novelist Dinaw Mengestu, from his review in The New York Times:

In the opening paragraph of Rahul Bhattacharya’s first novel, “The Sly Company of People Who Care,” the unnamed narrator, a former cricket journalist from India, declares his intentions for his life, and thus his story — to be a wanderer, or in his words, “a slow ramblin’ stranger.” That rambling, through the forests of Guyana; the ruined streets of its capital, Georgetown; and out to the borders of Brazil and Venezuela, constitutes the novel’s central action. But its heart lies in the exuberant and often arresting observations of a man plunging himself into a world full of beauty, violence and cultural strife.

The Kirkus review of Mike Magner’s Poisoned Legacy:

This angry investigative report begins well before the 2010 Deepwater Horizon catastrophe.

In the first chapter, National Journal editor Magner describes a possible cancer epidemic in a Kansas town where refinery wastes have poisoned a wide area and where a courageous retired schoolteacher is fighting an uphill battle to force BP to clean up. Apparently, he had been researching this problem when the Gulf blowout forced him to change the book’s focus, but both stories alternate throughout the narrative. Readers with a taste for heated fist-shaking will have plenty of opportunities as Magner delivers detailed accounts of BP’s mishaps, emphasizing the massive 2005 Texas refinery explosion, leaks and malfunctions along the Alaska pipeline and the Deepwater disaster. Each follows an identical pattern: BP officials cut costs, safety budgets drop, employees grumble and warn of disaster, disaster occurs, individuals who suffered terribly tell their stories and government regulators and the media suddenly show interest, resulting in an outpouring of outrage, investigations, damning reports, fines and apologies from BP executives and the inevitable avalanche of lawsuits. Magner makes a strong case for BP’s negligence and the American government’s feeble oversight, but his case that BP operates less competently than other oil companies is not as convincing. Perhaps wisely, the author makes no argument that Americans are willing to make the painful sacrifices necessary to ensure that these catastrophes never recur. We want oil, and we don’t want it to cost too much.

A relentlessly critical denunciation of the latest environmental disaster that leaves the impression that more will follow.

Groove Interrupted immediately piqued my interest and quickly found its way into my stack. Excerpt from Jazz Time’s review:

New Orleans native Spera, a longstanding music writer for The Times-Picayune who was also part of the newspaper’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Hurricane Katrina coverage team, focuses on tales of musicians confronting the challenges of trying to continue to make music in a post-Katrina environment. He covers those displaced New Orleanians forced to seek refuge in Houston, Austin, Nashville and other points around the country in the wake of Hurricane Katrina (known around New Orleans as “the Federal flood”). His profile of the cantankerous, Slidell-based blues guitarist-singer-fiddler Gatemouth Brown, who succumbed to lung cancer shortly after Katrina hit, is particularly moving, as is his eloquent recounting of Aaron Neville’s escape from his beloved hometown in the face of Katrina, his subsequent mourning over the loss of his wife to lung cancer in 2006 and triumphant return to New Orleans in 2008.

Nice little stack from the good people at Picador—novels, reissues, first-time-in-trade-paperbacks, nonfiction . . . a nice little spread.

Nice little stack from the good people at Picador—novels, reissues, first-time-in-trade-paperbacks, nonfiction . . . a nice little spread.