“Just Asking”

by

David Foster Wallace

First published in The Atlantic, 2007

Are some things still worth dying for? Is the American idea* one such thing? Are you up for a thought experiment? What if we chose to regard the 2,973 innocents killed in the atrocities of 9/11 not as victims but as democratic martyrs, “sacrifices on the altar of freedom”?* In other words, what if we decided that a certain baseline vulnerability to terrorism is part of the price of the American idea? And, thus, that ours is a generation of Americans called to make great sacrifices in order to preserve our democratic way of life—sacrifices not just of our soldiers and money but of our personal safety and comfort?

In still other words, what if we chose to accept the fact that every few years, despite all reasonable precautions, some hundreds or thousands of us may die in the sort of ghastly terrorist attack that a democratic republic cannot 100-percent protect itself from without subverting the very principles that make it worth protecting?

Is this thought experiment monstrous? Would it be monstrous to refer to the 40,000-plus domestic highway deaths we accept each year because the mobility and autonomy of the car are evidently worth that high price? Is monstrousness why no serious public figure now will speak of the delusory trade-off of liberty for safety that Ben Franklin warned about more than 200 years ago? What exactly has changed between Franklin’s time and ours? Why now can we not have a serious national conversation about sacrifice, the inevitability of sacrifice—either of (a) some portion of safety or (b) some portion of the rights and protections that make the American idea so incalculably precious?

In the absence of such a conversation, can we trust our elected leaders to value and protect the American idea as they act to secure the homeland? What are the effects on the American idea of Guantánamo, Abu Ghraib, Patriot Acts I and II, warrantless surveillance, Executive Order 13233, corporate contractors performing military functions, the Military Commissions Act, NSPD 51, etc., etc.? Assume for a moment that some of these measures really have helped make our persons and property safer—are they worth it? Where and when was the public debate on whether they’re worth it? Was there no such debate because we’re not capable of having or demanding one? Why not? Have we actually become so selfish and scared that we don’t even want to consider whether some things trump safety? What kind of future does that augur?

FOOTNOTES:

1. Given the strict Gramm-Rudmanewque space limit here, let’s just please all agree that we generally know what this term connotes—an open society, consent of the governed, enumerated powers, Federalist 10, pluralism, due process, transparency … the whole democratic roil.

2. (This phrase is Lincoln’s, more or less)

In his

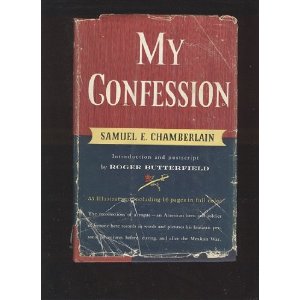

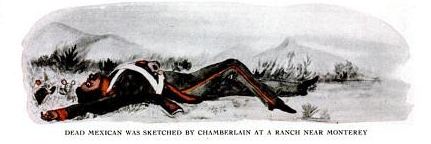

In his  According to Chamberlain, John Glanton was born in South Carolina and migrated to Stephen Austin’s settlement in Texas. There he fell in love with an orphan girl and was prepared to marry her. One day while he was gone, Lipan warriors raided the area scalping the elderly and the children and kidnapping the women- including Glanton’s fiancee. Glanton and the other settlers pursued and slaughtered the natives, but during the battle the women were tomahawked and scalped. Legend has it, Glanton began a series of retaliatory raids which always yielded “fresh scalps.” When Texas fought for its independence from Mexico, Glanton fought with Col. Fannin, and was one of the few to escape the slaughter of that regiment at the hands of the Mexican Gen. Urrea- the man who would eventually employ Glanton as a scalp hunter. During the Range Wars, Glanton took no side but simply assassinated individuals who had crossed him. He was banished, to no avail, by Gen. Sam Houston and fought as a “free Ranger” in the war against Mexico. Following the war he took up the Urrea’s offer of $50 per Apache scalp (with a bonus of $1000 for the scalp of the Chief Santana). Local rumor had it that Glanton always “raised the hair” of the Indians he killed and that he had a “mule load of these barbarous trophies, smoke-dried” in his hut even before he turned professional.

According to Chamberlain, John Glanton was born in South Carolina and migrated to Stephen Austin’s settlement in Texas. There he fell in love with an orphan girl and was prepared to marry her. One day while he was gone, Lipan warriors raided the area scalping the elderly and the children and kidnapping the women- including Glanton’s fiancee. Glanton and the other settlers pursued and slaughtered the natives, but during the battle the women were tomahawked and scalped. Legend has it, Glanton began a series of retaliatory raids which always yielded “fresh scalps.” When Texas fought for its independence from Mexico, Glanton fought with Col. Fannin, and was one of the few to escape the slaughter of that regiment at the hands of the Mexican Gen. Urrea- the man who would eventually employ Glanton as a scalp hunter. During the Range Wars, Glanton took no side but simply assassinated individuals who had crossed him. He was banished, to no avail, by Gen. Sam Houston and fought as a “free Ranger” in the war against Mexico. Following the war he took up the Urrea’s offer of $50 per Apache scalp (with a bonus of $1000 for the scalp of the Chief Santana). Local rumor had it that Glanton always “raised the hair” of the Indians he killed and that he had a “mule load of these barbarous trophies, smoke-dried” in his hut even before he turned professional.

It’s fascinating to note how much of the Judge is already there–the pedophilia, the marksmanship, the scholarship, and, most interesting of all, the lack of hair. Confession goes on to detail the killing, scalping, raping, and raiding spree that comprises the center of Blood Meridian. Chamberlain even describes the final battle with the Yumas, an event that signals the dissolution of the Glanton gang in McCarthy’s novel.

It’s fascinating to note how much of the Judge is already there–the pedophilia, the marksmanship, the scholarship, and, most interesting of all, the lack of hair. Confession goes on to detail the killing, scalping, raping, and raiding spree that comprises the center of Blood Meridian. Chamberlain even describes the final battle with the Yumas, an event that signals the dissolution of the Glanton gang in McCarthy’s novel.

Content aside, Chamberlain’s prose also seems to presage McCarthy’s prose. In his book

Content aside, Chamberlain’s prose also seems to presage McCarthy’s prose. In his book  You can view many of Chamberlain’s paintings and read an edit of his Confession in three editions of Life magazine from 1956, digitally preserved thanks to Google Books–here’s

You can view many of Chamberlain’s paintings and read an edit of his Confession in three editions of Life magazine from 1956, digitally preserved thanks to Google Books–here’s

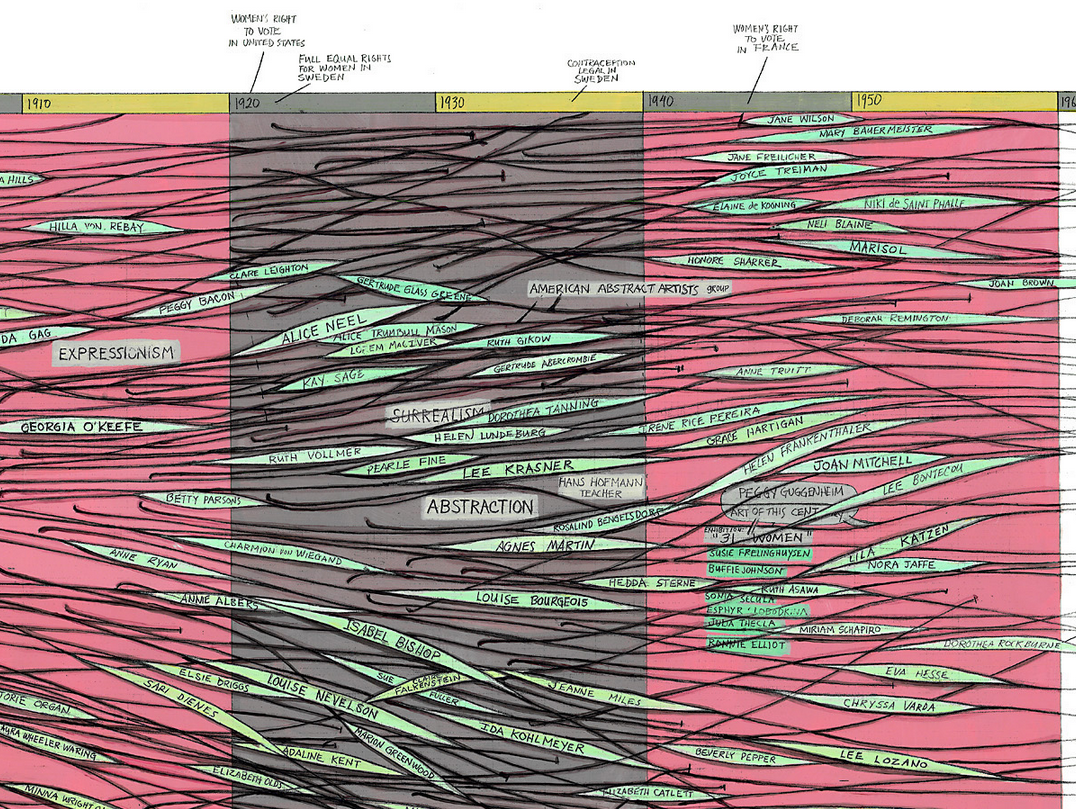

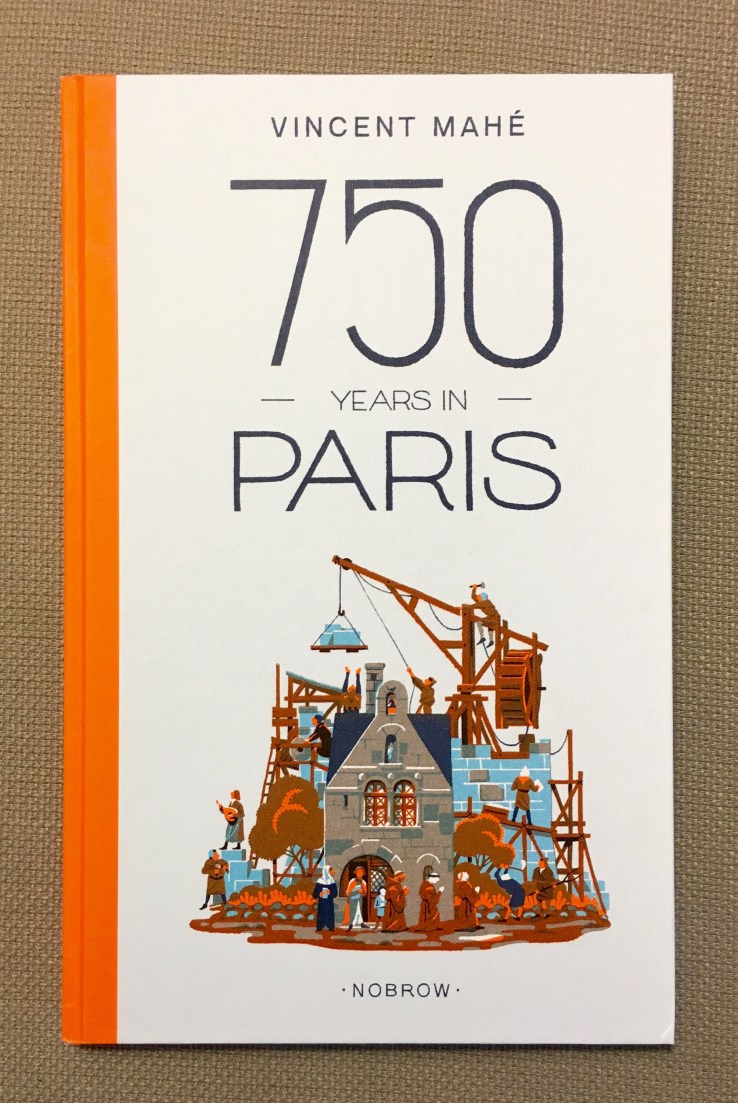

The book ends in 2015; I’ll let Mahé’s image speak for itself:

The book ends in 2015; I’ll let Mahé’s image speak for itself: